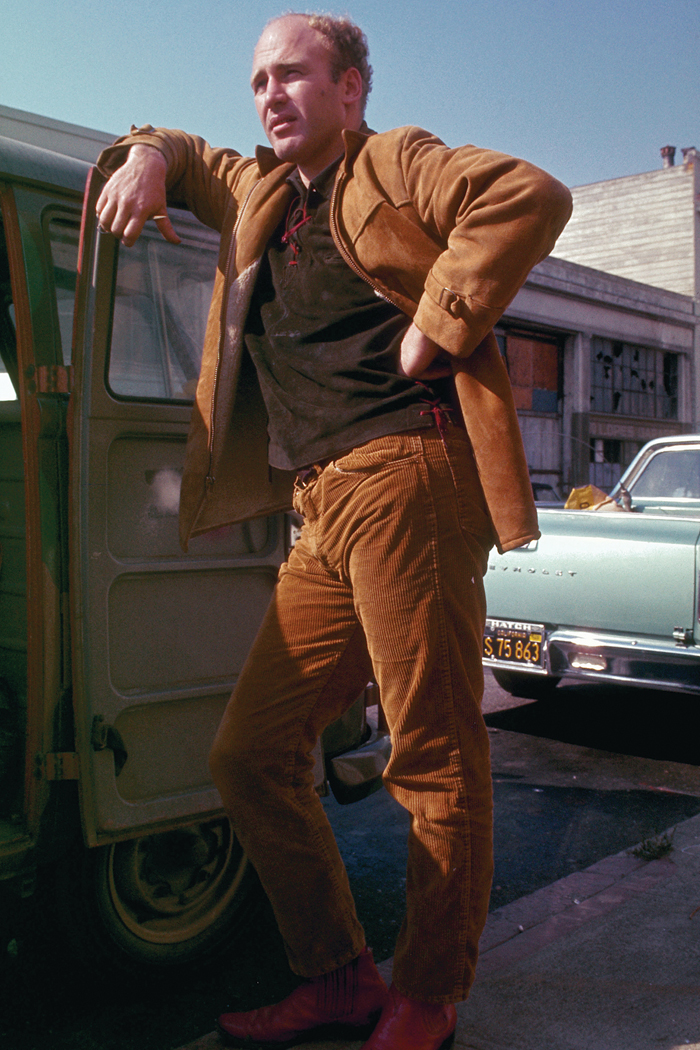

Ken Kesey in Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place, dir. Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood, Magnolia Pictures, 2011. Photo: © Ted Streshinsky, Corbis.

In the fall of 1963, Ken Kesey drove from his home in La Honda, California, to New York City to see the premier of the stage adaptation of his novel, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. While in New York, Kesey and his friends traveled out to Flushing, Queens, where preparations for the 1964 World’s Fair were underway. Twenty-five years earlier, a World’s Fair on the same site had promised “The World of Tomorrow” and the “Dawn of a New Day.” Tomorrow came and went, bringing with it a series of hot and cold wars, America’s military domination of the globe, and a general, looming dread of how it might all be undone at any moment. The 1964 World’s Fair promised a different future. Kesey spotted the Unisphere under construction. The twelve-story-high gridded steel globe was circled by interlocking hoops, which looked like the racing paths of electrons around an atom or satellites orbiting through space. The Unisphere was the symbol of the exhibition’s themes: “Man’s achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe” and “Peace through Understanding.” President Kennedy launched the construction of the site by picking up the phone (a white one, not red) in his office and dialing “1-9-6-4.” it is easy to see the nuclear references in the icon and its “launch” as an anxious reiteration of the Cold War threats, but the structure and its accompanying themes were much more ambivalent. The military and secular technologies that had shrunk the globe–satellites, NASA rockets, television, telephones, and, soon, the internet (which began to take shape at advanced research Projects Agency (ARPA) in 1962, and went live in 1969)–were the same ones that were expanding the universe. There were more ways to get in touch and learn about each other, more ideas and more people available for contact. on the way home from New York, Kesey heard word of JFK’s assassination over the radio. An all-encompassing mass-affect spread over the air and touched all the people Kesey saw as he crossed each state’s line. “Everyone felt the same pain,” he reminisced. If peace were going to come, the fair’s theme seemed to suggest, it would come through a technologically enabled and mediated understanding of each other and the systems we inhabit.

Aerial View Of The Unisphere and other exhibits at 1964 World’s Fair, New York, World Telegram & Sun, photo: Roger Higgins. Library Of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-DIG-DS-00864.

Kesey attempted to harness the possibility of mass-affect he experienced over the radio and spread some of his own peace and understanding though the technologies he had at hand, particularly 16 mm film and LSD. Both enabled a confusion of space, time, and points of view that simultaneously shrank Kesey’s world and expanded his universe by connecting him to the consciousnesses of the people (and things) that surrounded him. By coming closer together, the universe became larger, more expansive, and more fascinating.

Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood’s new documentary, Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place (2011), recounts Kesey’s second cross-country trip back to New York, which Tom Wolfe made famous in his “literary journalism” opus, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968). In the summer of 1964, Kesey and his cohort of Merry Pranksters returned to Queens in a customized, hand-painted 1939 school bus named “Further,” which was outfitted with bunk beds, 16 mm cameras, a high-tech sound system, and enough LSD to get them from California to New York in high style.1 Jack Kerouac’s inspiration for On the Road, speed-freak Neal Cassady, was the responsible adult at the wheel. Along the way they crossed paths with other artists and counterculture icons, such as Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Larry McMurtry.

To write his nonfiction novel, Wolfe interviewed Kesey and the Pranksters, and then retold the story of Kesey’s move “beyond” writing to a large-scale, LSD-fueled film project documenting the experience of living on the road in an interconnected, inter-subjective, highly medicated state of “being in the now.” For their documentary film, Gibney and Ellwood had a different set of primary documents at their disposal–UCLA’s recently preserved archive of the Merry Pranksters’ film and audio recordings from the 1964 trip. The trip resulted in almost fifty hours of film and even more taped sound. For years, Kesey unsuccessfully tried to finish the film, The Merry Pranksters Look for a Cool Place,2 but eventually abandoned the project before his death in 2001. In the years following the trip, he screened various edited and unedited “expanded cinema” versions of the film at his legendary multimedia party-performances, the Acid Tests. Kesey’s immersive events were West Coast predecessors to andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966). Kesey’s film was accompanied by live performances of the Grateful Dead and roy Seburn’s light shows. The synesthetic effects of the pulsing light, psychedelic sounds, and hard drugs were an attempt to put viewers “on the bus,” to connect them to the experiences and consciousnesses of the Pranksters in the film and the audience that surrounded them.

Gibney and Ellwood’s documentary skips over these experimental screenings in service of their alternating claims that Kesey’s film had “never been seen,” was “virtually never seen,” or that “few ever saw the film.”3 What the filmmakers seem to mean is that Kesey’s film had never been seen like this: as a comprehensive and comprehensible linear account of the Merry Pranksters, their trip, its ambitions, and, most emphatically in their documentary, its failures. Gibney and Ellwood tame Kesey’s unwieldy, kinetic footage into a brisk, informative, and often-inventive illustration of the trip and the sequence of events that led up to it. They fleshed out the story with stock footage and still photos from the 1960s, and staged reenactments of key moments from Kesey’s life. The directors recreated word-for-word a mind-blowing audio recording of Kesey’s first LSD trip, administered by a nurse at a Veterans’ Hospital. Under the influence of a 1960 archival recording made at the hospital, the directors make the blank walls of a clinical room come to life with twitching overlays of animated figures and handwriting borrowed from Kesey’s own drawing style. The purposefully bland hospital room pulses with the hallucinations Kesey describes: he sees “mathematical patterns: hexagons, pentagons, and mummies.”

To include Kesey’s own footage of the bus trip in Magic Trip, the documentarians employed lip readers to help them sync the miles of audiotape to the film, but this proved difficult, if not impossible, for most of the archive. instead, Gibney and Elmwood hired actors to dramatically read transcripts of Pranksters interviews that help to narrate and ground the footage in the chronology of the trip. A fictional off-screen interviewer, voiced by an uptight Stanley Tucci doing his best radio personality impression, “interacts” with the various recorded interviews, weaving the fractured narratives into one continuous, lucid story.

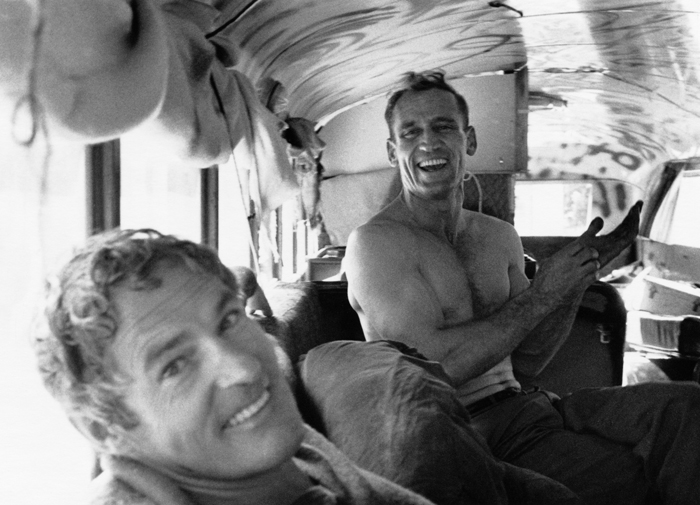

The disciplining of Kesey’s naive, experimental footage of youthful rebellion was clearly a hard-won battle. The Pranksters’ many edits of the film had left the prints in tatters. The sheer volume of the archive and the nearly total lack of sync-sound made structuring a conventional documentary a daunting task. Neither Kesey nor any of the Pranksters had felt satisfied with their attempts at editing the film. According to Prankster and group photographer Ron Bevrit, the footage didn’t lend itself to conventional cinema: “it was jiggling and out of focus; it lacked establishing shots that could structure a story and it had no plot.”4 The original film worked on the simple assumption that the Pranksters would record an open-ended adventure, and that the trip would be more important than the destination. Kesey reminds the interviewer that the name of the bus, “Further,” is not a distance but “a philosophical concept.” The bus did not just move from here to there in time and space; it was on a metaphysical journey. Each moment of Kesey’s film nested in Magic Trip is thrilling because the viewer is uncertain what will happen next, if anything at all. Just like the passengers on the bus, the viewer of Kesey’s film must surrender to the trip, see where it leads, and make up her own answers and meaning.

The Bus in Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search For a Kool Place, dir. Alex Gibney And Alison Ellwood, Magnolia Pictures, 2011. Photo: © Ted Streshinsky, Corbis.

At multiple moments in the documentary, Gibney and Ellwood excerpt Kesey talking about his reasons for leaving writing for film, and the philosophy behind his cinematic style:

There’s been a one-step removal from our connection to life. We can’t see anymore, we can barely hear anymore; when we look, we are not looking at, we are looking for. Hollywood is a soulless idea of what life looks like… all you can do is experience the thing. This, as near as I can see, is what’s going on, as near as I can record it. It may not make sense. I’m just trying to pick up the camera and see it clearly for a moment.

Hollywood–its structures, plots, scripts, beginnings, endings, and theater seating–is unsuitable for the kind of experience Kesey was trying to create on the bus, at the Acid Tests, and in his movie. The film was not shot with intention (or even the knowledge) of continuity editing and Hollywood codes of filmmaking. It put aside all of those artificial structures of viewing and perception that govern cinema, and naively surrendered to the camera’s ability to be “there” in the moment, and to bring that moment back to life at a later time.

Timothy Leary and Neal Cassady in Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place, dir. Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood, Magnolia Pictures, 2011. Photo: © Allen Ginsberg, Corbis.

The screening scenarios for Kesey’s film couldn’t have been further removed from the typical cinematic experience. Wolfe describes the 1965 screening at Muir Beach:

Two projectors shine forth with The Movie. The bus and the Pranksters start rolling along the walls of the lodge, Babs and Kesey rapping on about it, the bus lumping huge and vibrating and bouncing in great swells of heads and color… The Movie and Roy Seburn’s light machine pitching the intergalactic red science-fiction seas to all corners of the lodge, oil and water and food coloring pressed between plates of glass and projected in vast size so that the very ooze of cellular Creation seems to extoplast into the ethers and the Dead coming in with their immense submarine vibrato vibrating…5

If the cinematic experience of the original forms of The Merry Pranksters Look for a Cool Place gave the viewer the experience of “being on the bus,” it was not in the sense that the viewers feel as if they were literally on the bus with the Pranksters, but that the viewing experience required just as much surrender to the unpredictability of the trip as being on the bus did. The Pranksters achieved this unguarded openness through drugs; the viewer was aided by a different technology–film, and its indexical force that pushes past moments into the “now.”

In Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place, Kesey’s film finds its commercial, narrative form and consequently its failure. While the directors argue that Kesey made a permanent imprint on how we remember the 1960s, they frame his experiments as failures within their narrative. When the Pranksters arrived at the World’s Fair, they were sorely disappointed. Its vision of the future was already in the Pranksters’ rearview mirror. The trip had pushed them into a future even the Fair couldn’t have predicted. They were already living in 1968 while the rest of america was still in 1964. The “Better Living through Chemistry” advertized at DuPont’s pavilion was not the kind of chemistry that interested the Pranksters. Even their own better living through LSD became somewhat tainted when Kesey discovered, via Allen Ginsberg campaigning for the release of government documents, that his introduction to LSD was part of the CIA’s MKULTRA experiments in mind control. After the Acid Test Graduation (1966) and a brief stint in jail for marijuana possession, Kesey moved his family back to rural oregon. The final moments of Magic Trip show Kesey working his family farm, riding tractors, hunting with a rifle, and “Further” rotting in the woods. The bus, which Kesey considered his “greatest work,” was left to be consumed by moss and mold and vines. The Pranksters had all been flushed from the farm when Kesey realized that their antics posed a threat to a stable and safe life for his children.

Gibney and Ellwood’s Magic Trip depicts Kesey’s aesthetic experiment in psychedelic living as an ill-fated adventure that accidentally created slums of teenage burn-outs in the Haight and unknowingly served (if not also subverted) a CIA experiment aimed to create docile citizens. It also implies that Kesey’s attempt to change cinema was a failure too. To be fit for consumption by the average filmgoer, Gibney and Ellwood structure and normalize Kesey’s wild takes. it could not be “seen” by the American public until it conformed to the very standards of continuity, linearity, narrative, and plot that it tried to circumvent. Kesey may have changed how the 1960s looked, but it seems that he didn’t change the audience or what it expects from cinema. While the directors were able to work the original footage into a standard story, the clips still exude the joyous lawlessness and freedom from convention that inspired them and might seduce still more filmmakers with an archival impulse to dig through UCLA’s collection and find Kesey’s Day-Glo painted film cans.

The expanded cinema practices that Kesey pioneered, of course, synced with the experimental film practices we’ve come to associate with the 1960s and 1970s, especially by Warhol and Stan VanDerBeek. But even beyond this legacy, Kesey’s bus trip and the film screenings that came out of it were deeply connected to other counter-cultural media movements taking shape in the mid-1960s that aimed to reimagine how we used technology and media, and how we engaged with each other. Some of the plot points from Kesey’s film and pharmaceutical projects that Gibney and Ellwood skip over, such as the Acid Tests, hold open the possibility of Kesey’s impact on how we use and conceive of our media tools.

The title of Kesey’s film, The Merry Pranksters Look for a Cool Place, unconsciously echoes Marshal McLuhan’s media critiques of the same year. All media, McLuhan argued, are either hot or cool. Hot media are “well filled in with data” and activate one sense at a time. Photographs, the radio, and print are hot. They activate the eye or the ear alone. Film is a hot medium too, despite its joining of image and sound. Its high-definition and un-responsive, already complete nature leaves little for the viewer to add in. Cool media, on the other hand, demand completion by the audience. They require participation. Telephones, speech, and television are some of McLuhan’s examples cool media. They require the receiver to give as much as she gets to make the system work. Television is a curious cool medium; despite its (potential) liveness, its unidirectionality seems to leave little room for viewer participation. The kind of participation that McLuhan imagines with television, however, is synesthetic rather than simple call and response, like with the telephone. His reasoning involves the fact that the television is low definition: only half the scan lines are ever present on the screen at any given time. To complete the image, the viewer must run her eyes across the image as if they were her hands, to smooth it over. McLuhan writes: “The TV image requires that we ‘close’ the mesh by a convulsive sensuous participation that is profoundly kinetic and tactile, because tactility is the interplay of the senses, rather than the isolated contact of skin and object.”6 Vision in television becomes linked to touch. Multiple senses are activated and exchanged in the process of watching.

Neal Cassady in Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search For a Kool Place, dir. Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood, Magnolia Pictures, 2011. Photo Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Kesey and the Pranksters, of course, were shooting on film (portable video cameras would not become available until 1968), but The Merry Pranksters Look for a Cool Place can be understood as an attempt to “cool” down hot Hollywood film. McLuhan wrote in an aphoristic style to add participation and reader engagement into the hot medium of writing. Kesey’s experiment with plotless, open-ended, out of order cinema, coupled with psychedelic music and drugs, engaged viewers in the perpetual, perceptual “fill-in” of cool media. Cool media and the transformation of communications technologies that the 1960s brought were changing contemporary culture, according to McLuhan. They were retribalizing society, linking all of society in a “global village.” The Pranksters’ mobile living quarters were just one example of many “nomadic tribes” that took shape on the fringes of 1960s counterculture. New communications technologies, and the systems of interaction and participation they enabled, McLuhan argued, would dissolve the “lineal specialism and fixed points of view”7 of modern media society and give way to a “global embrace, abolishing both space and time.”8 McLuhan’s ideas about the electronic revolution rhyme with the Unisphere’s message of the shrinking globe and the expanding universe. Kesey was doing the best he could to create a new technological tribalism with hot film coupled with multimedia screenings and the consciousness-linking and

-expanding properties of LSD.

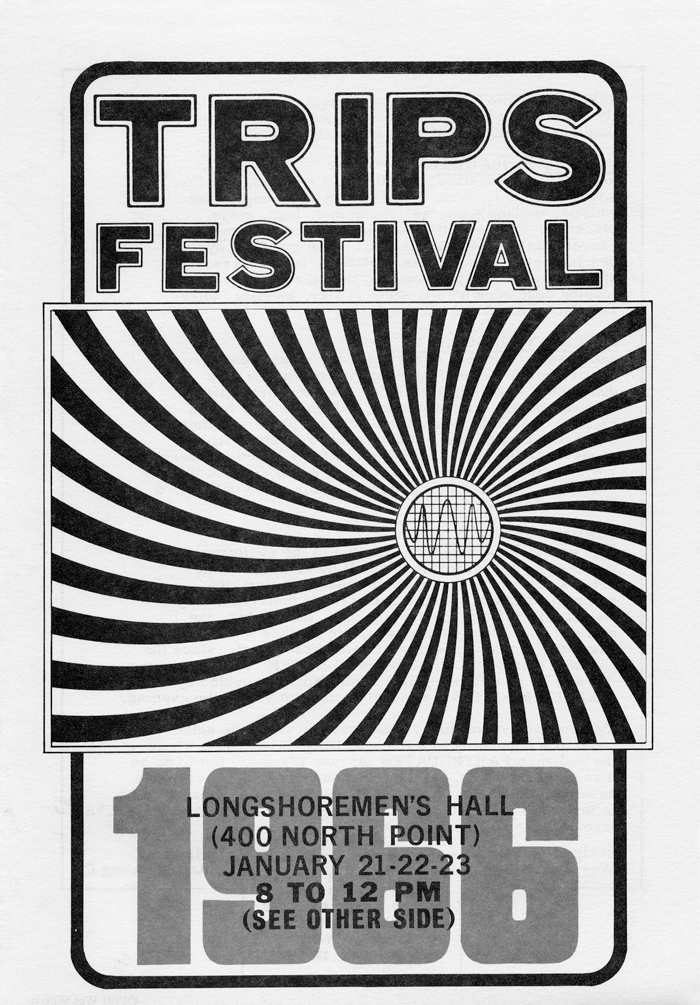

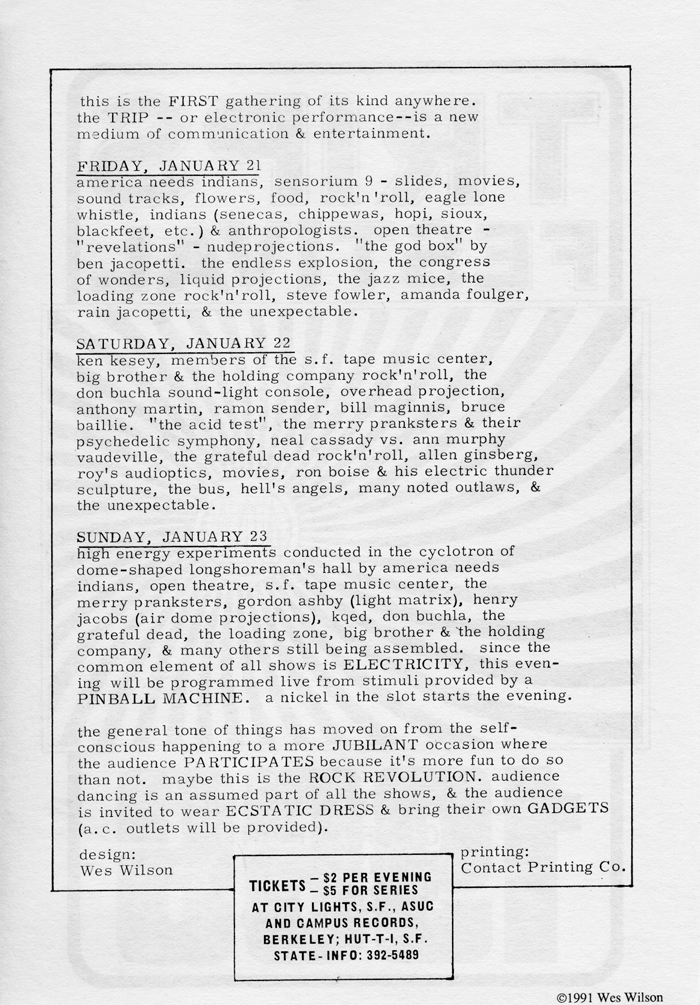

The idea that access to and engagement with the tools of media production could change consciousness ran deep in the Prankster philosophy. The Trips Festival, a collaboration between Kesey and Stewart Brand, the Prankster who founded the Whole Earth Catalog in 1968, brought together all of the technological toys and tools and synesthetic accoutrements available to the Pranksters in 1966. Psychedelic music by the Merry Pranksters, Jefferson airplane, the Grateful Dead, and Don Buchla on the synthesizer accompanied the film, slide and light shows, and scores of other events. While the three-day festival was packed with performances, Brand and Kesey defined the festival in less conventional terms. The advertising broadsheet describes The Trip as an “electronic performance” and “a new medium of communication & entertainment.” it was not intended to be a “self conscious happening, but jubilant occasion where the audience participates because it’s more fun to do so than not.” The attendees were encouraged to “bring their own gadgets (a.c. outlets will be provided).” The image on the broadsheet’s cover showed a graphic, psychedelic vortex of black and white lines. At its center the smooth sine wave of an oscilloscope snakes across a grid. The poster, Fred Turner notes, illustrates how “both LSD and small electronic devices served as technologies for the transformation of consciousness.”9

Wes Wilson, Trips Festival Handbill, 1966.

Wes Wilson, Trips Festival Handbill, 1966.

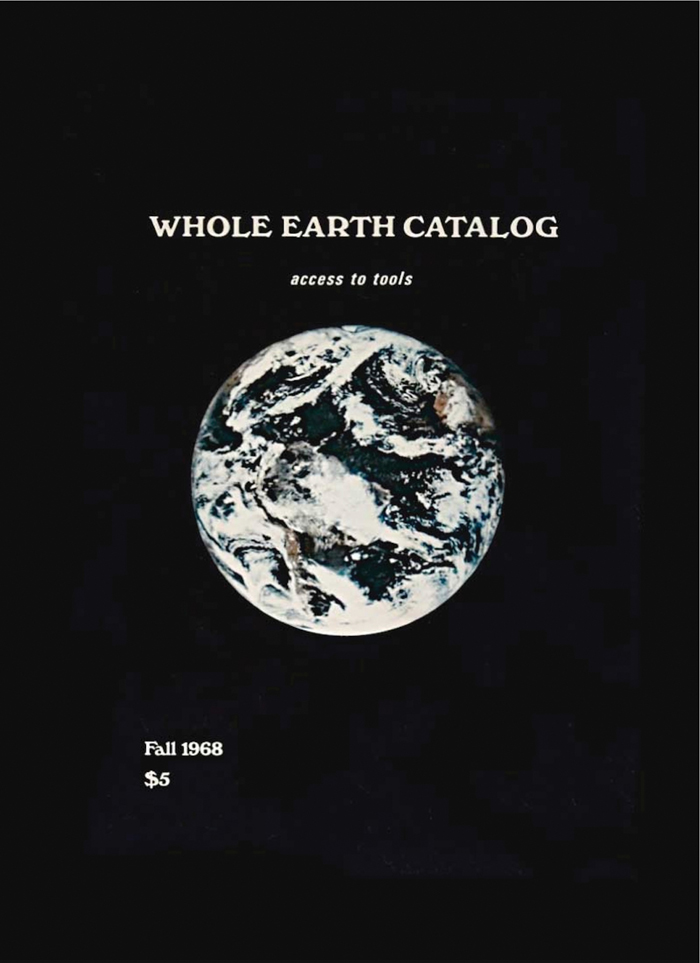

Whole Earth Catalog Cover, Fall 1968.

Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog ran with the subtitle, Access to Tools. The publication was a compendium of retailers of books, products, and technologies that would help individuals and groups move off the conventional grid of bureaucratic America, and go back to the land or on the road with all the tools and information they needed to change their consciousnesses and the way they lived their lives. Each issue of the catalog ran with a satellite picture of the Earth on the cover. The NASA image and the aims of the catalog modeled yet another Unisphere, another expanding universe and shrinking world. Brand invited Kesey to compile the final issue of the original-run Whole Earth Catalog, the March 1971 The Last Supplement to the Whole Earth Catalog. Rather than listing products and where to get them, Kesey’s “tools” were more loosely defined. Hemingway, booze, ginseng, the I Ching, and dope were part of Kesey’s “tool chest,” as were the City Lights Bookstore, Woody Guthrie, and the Grateful Dead. These were the tools he used to live his life. There were no directions about how to get a hold of them or how to use them. In the introduction to the Supplement, he argues that the work that must be done to save the “revolution” is “to try once again to function primarily as a pointer rather than a seller.”10 This phrase sums up Kesey’s projects of the mid-1960s. In the catalog, as well as at the film screenings, Acid Tests, and on the bus, Kesey proposes that things could be different–cinema, consciousness, and our relationship to others–by pointing toward a new path but not clearly showing the way.

Kris Paulsen is Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art, Film, Video, and New Media in the Department of History of Art at The Ohio State University