Working on paper or on [sculptural] pieces really is the same thing; it’s all one activity that I am not interested in separating. I get to a point in a drawing where I cannot make another move without making it three-dimensional.

–Al Taylor1

Drawing is an extension of thought.

–Joseph Beuys2

In one of his rarely published interviews, the New York artist Al Taylor (1948–99) talks about the relation between drawing and sculpture, and sets up a line of thought that runs throughout his oeuvre. In his work, drawing and sculpture inform one another constantly. In fact, drawing is a conceptual practice for Taylor not limited to two dimensions. The artist developed his visual language by making drawings rooted in observations of daily life, which he transferred into three-dimensional objects and sometimes returned to the two-dimensional plane of drawing. Throughout art history, the relationship between drawing and sculpture has been understood in a hierarchical order that privileges sculpture. Nevertheless, the place of drawing is still, and perhaps always, being discussed.3 Drawing is the medium that is understood to be closest to the thought or inspiration of the artist. Thus, the Renaissance concept of “disegno,” which encompasses drawing and design in regard to invention and concept, should be revived in reflecting on Al Taylor’s work.

Al Taylor, Pet Stain Removal Device, 1989. Bamboo garden stakes, plexiglas, paint, wire, and electrical tape; 49 x 24 1/4 x 48 ins. Collection of the artist. © 2010 The estate of Al Taylor. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

Taylor’s refreshingly non-hierarchical understanding of drawing and sculpture can be experienced in the exhibition “Al Taylor: Wire Instruments and Pet Stains” at the Santa Monica Museum of Art. As the title suggests, only two bodies of this prolific artist’s work are presented, giving the viewer a concentrated insight into the artist’s working mode and visualized thinking process. This is Taylor’s first solo exhibition in an American museum and, even though he deserves a retrospective, the narrow focus of this show is a careful and wise decision. It is evidence of a productive collaboration between curators Elsa Longhauser and Lisa Melandri and the artist’s widow, Debbie Taylor, who, since his passing, has devoted herself to the purposeful promotion of the artist’s legacy.4 At the exhibition’s opening, Debbie Taylor gave a talk that laid open the contradictions inherent in dealing with the artist’s work from a historical perspective. Speaking about his work would not have been Taylor’s style during his lifetime, since he wanted people to see and experience the work rather than explain it. With the utmost respect for this reticence, Debbie Taylor’s talk instead directed the audience’s attention to how the artist worked, and in so doing, brought out the artist’s humorous spirit.

I normally make drawings to forget (record) something that I have been thinking (looking) about; but it usually backfires and just gives me something new to think (look) about (to record). I don’t think too well, but I can look o.k.

–Al Taylor5

Al Taylor’s understanding of drawing closely follows his visual perception, which is equally conceptual and process-oriented. Sculpture in Taylor’s work is the logical extension of drawing, following his perception into a spatialization of line. Unlike other definitions of sculpture, this work is not about the mastery of surface and volume, but rather about spatial perception. While the above quote suggests that drawing permits him to record his observations and thoughts, his extension of drawing into three dimensions brings other elements to the foreground. The resulting works suggest both movement and time. Allowing the viewer to see an object from multiple angles while still asserting the two-dimensional plane of the drawing creates a fascinating oscillation between drawing and sculpture.

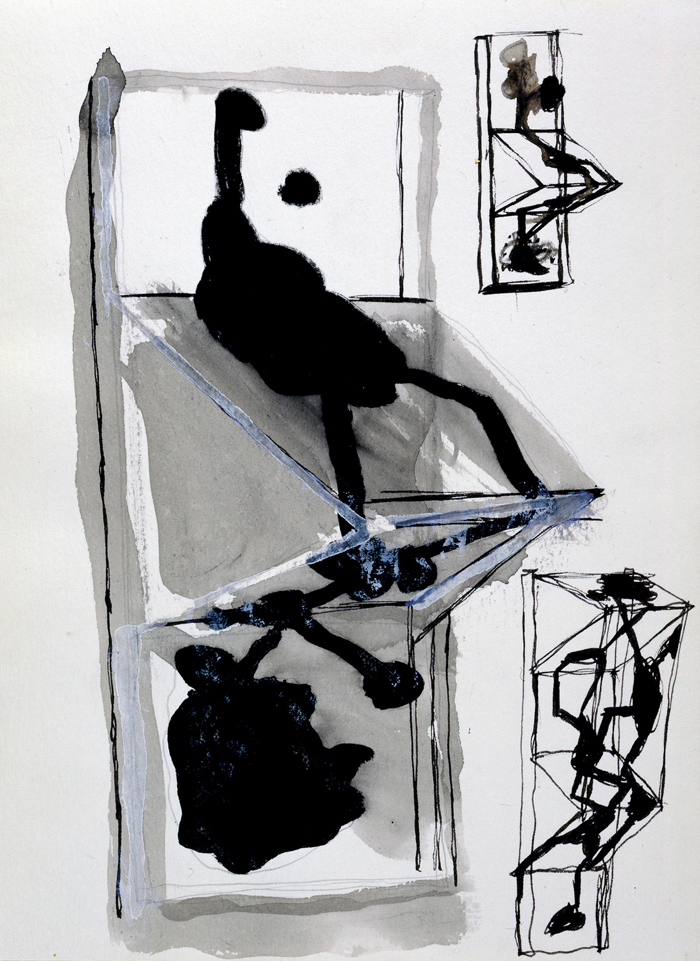

Al Taylor, Pet Stain Removal Device, 1989. Pencil, gouache and ink on paper torn from spiral ring sketchbook (with pencil sketch on verso). 12 x 9 ins. Collection of the artist. © 2010 The estate of Al Taylor. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

The series Wire Instruments (1989–1990) and Pet Stains (1989–1992) show the artist’s preference for and interest in found objects and imagery.6 Not only do the two projects overlap in time, they also relate to one another through their common use of ordinary materials such as wood, wire, and paint for the objects, and pencil, ink, gouache, crayon, and correction fluid for the drawings. However, both series situate themselves in different art genealogies. Wire Instruments, hanging from the wall, relate to Pablo Picasso’s guitars, Vladimir Tatlin’s counter reliefs, and the Wire Drawing series of Richard Tuttle, while Pet Stains on first impression seem to come closer to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. Looking again, however, we realize that Pollock and Taylor couldn’t be further apart. Pollock’s drip paintings and drawings are a performative act, rather seriously invested in abstraction. Taylor’s drips are not generated by specific body movements, and are certainly not heroic ones that play out any agenda of masculinity.7 As Cornelia Butler observed: “Taylor’s “pet stain” is both an abstract mark, standing in for authorship and the heroic mark, and literally the mark of everyday life, seeping indelibly into the realm of art.” Referring to the work No Title (1989), she continues: “Taylor’s innocuous, white painted lump on the floor is funny. Not inert, it has personality somehow.”8 Thus, any reference we might make to Pollock when looking at Taylor’s work must be made with a wink. In lightly skewering the heroic pretensions in art history, Taylor reminds us not to take ourselves too seriously. One cannot help but smile when looking at the pieces and titles of Taylor’s work, such as Pet Stain Removal Device (a series of drawings and sculptures, 1989), or Decoy (drawing and sculpture, 1989).

Al Taylor, Wire Instrument, 1989. Pencil, gouache, and ink on paper; 12 x 9 ins. Collection of the artist. © 2010 The estate of Al Taylor. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

Two stories are connected to the initial moment of finding and founding the “pet stains.” One has the artist in Paris— Montmartre, no less—gazing out his window, inspired by the pools and drips left by city dogs along Avenue Junot.9 But his friends tell another story, more rooted in daily life, about Taylor’s very old dog Wrecks, who left pee stains everywhere.10 The Montmartre anecdote makes the better artmaking-myth, of course, and both stories might be true. In any case, both declare a “pet stain” as a valuable visual form, which the artist analyzed from different angles in various ways.

Al Taylor, Station of the Cross, 1990. Formica laminate and wire, 42 1/4 x 25 1/2 x 23 ins. © 2010 The estate of Al Taylor. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

Taylor’s work is less connected to Pollock and more to Marcel Duchamp. In fact, Duchamp can be seen as Taylor’s forebear on various levels. The use of found objects, language, humor, and the notion of measuring, as well as an interest in indexical signs, are important elements for both artists.11 As Rosalind Krauss states, “Indexes establish their meaning along the axis of a physical relationship to their referents. They are the marks or traces of a particular cause, and that cause is the thing to which they refer, the object they signify.”12 A pet stain is the indexical sign of a pet peeing. Taylor’s “pet stains” evolved from stains as indexes to stains as icons. Rather than referring to anything, they become images with their own qualities, presented in two or three dimensions. His subject matter is equally representational and abstract—banal and scatalogical but simultaneously unfixable and beautiful. Taylor’s ways of seeing, his sense of humor, and his experimental approach to dimensions definitely made its mark in contemporary art.

Doris Berger is a curator and scholar who is interested in the relationship between media and disciplines. She wrote her PhD on the representation of visual artists in biopics. Prior to that she was the director of the Kunstverein Wolfsburg, Germany. Currently, she is working on a Pacific Standard Time-related project about the artistic exchange between California and Germany in the 1970s, which will result in a video and symposium at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in January 2012. She will be a Getty Postdoctoral Fellow in the academic year of 2011/12.