Gala Porras-Kim, Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, 2021. Installation view, Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, Amant, New York, November 20, 2021-March 13, 2022. Courtesy of Amant. Photo: Shark Senesac.

Like the organ trade, the necropolitical colonial museum survives off the control and regulation of the nerve centers of agency. It confers toxicity onto ambiguous objects, perversely poisoning the institution’s metabolism and calling out for new systems of healing.

— Clémentine Deliss, The Metabolic Museum

In November 2021, Jane Pickering, the director of the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnography at Harvard University, received an unusual letter from Los Angeles-based artist Gala Porras-Kim. Throughout Porras-Kim’s 2019-20 fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advance Study at Harvard University, the artist had been exploring how a collection of Mesoamerican ritual offerings to the Mayan rain god, Chaac, had come to be in the possession of the Peabody Museum. Like the overwhelming majority of archeological objects in Western museums, the offerings had been extracted from their original context and acquired by the Peabody through a series of legal loopholes. In the early twentieth century, an American diplomat named Edward H. Thompson was able to dredge the Sacred Cenote of Sacrifice, a naturally occurring limestone pool at Chichén Itzá, in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, on the technicality that it was a natural structure rather than a manmade one. When the objects began to crumble and break after being extracted from the cenote, they were glued together with binding agents and subjected to numerous other conservation practices in order to allow them to withstand being kept above water.

With the letter, Porras-Kim was hoping to begin a conversation with Pickering not about restitution but about the object’s present state of conservation and display within the museum’s collection: “Your storage, being one of the driest environments in which they can exist, is in complete opposition to their submerged wet state, and their current condition as historical artifacts might make it difficult to realize their purpose with the rain.”

A museum’s duty of care for an object, the letter goes on, should not be limited to the physical conservation of its material form but rather should extend to the immaterial preservation of the object’s latent ritual functions. As phrased by Diana Taylor, “Caring acknowledges the interconnectedness between ourselves and others, ourselves as only part of that large entity.”1 Moreover, care suggests ownership as a temporary condition, one requiring an attentive and regulated commitment to an object’s integrity, even if it means having to act against one’s best economic interests.2 Porras-Kim’s letter, titled Mediating with the Rain (2021-ongoing), forms the centerpiece of Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, a solo exhibition at Amant composed largely of drawings, installations, and many letters that consider cultural artifacts and heritage that have been displaced from their sites of origin or interfered with other ways: a plundered Mexican pyramid, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Turkey, the incinerated remains of a young woman discovered in Brazil in the 1970s. The works are complex and heavily researched meditations on how alternative models of care might open space for different narratives and immaterial imaginaries to coexist with the systems of meanings and value prescribed to objects by institutions.

In Amant’s larger gallery, a basin installed above the ceiling vent is calibrated to drip rainwater every 20 seconds onto a rectangular block cast from dust and copal, a clear resin often burned as incense in ceremonies and the main material dredged from the Mayan cenote. Precipitation for an Arid Landscape (2021), from which the exhibition takes its name, is part of the same body of work as the letter to Pickering, and it expands on the premise that the dredged objects’ material qualities have been altered to the extent that they presently take the form of dust held together by an external agent. The copal acts as proxy for the volume of artifacts removed, while the dust, collected from the Peabody’s storage unit, comes from the objects themselves—perhaps in reference to the way museums acquire objects only to take them out of circulation and confine them to a life in storage. Mixed with rainwater, the sculpture is meant to facilitate a reunion of the collected objects with Chaac, allowing them to continue fulfilling their ritual function and restoring their spiritual sanctity. Porras-Kim importantly outsources the water component of the sculpture to Amant as part of the negotiated conditions of the exhibition, thus delegating the physical and mental labor of realizing the work to the institution.

Gala Porras-Kim, 931 Offerings for the Rain at the Peabody Museum, detail, 2021. Color pencil and flashe on paper, 72 × 72 in. © Gala Porras-Kim, courtesy of Amant, New York.

This last element bears a comparison to Félix González-Torres’s certificates of authenticity—the legal documents used by the artist both to verify his works’ authenticity and explain their parameters. More permissive than prohibitory, the certificates treat collectors of González-Torres works almost as collaborators, factoring noneconomic qualities like respect and trust into contractual relationships more often than not bound by market interests and a legal aversion to risk. As Joan Kee notes: “The certificates of González-Torres proposed an alternative vision of possession as a fluid condition, with the owner having both unprecedented flexibility and responsibility from the moment of acquisition to when or if the work was sold.”3 Similarly, the range of potential ways to realize Precipitation for an Arid Landscape is at odds with the tendency of museums to acquire objects and submit them to institutional norms that render them both immobile and immortal. With each puddle that forms on its surface and causes the smooth slab to crack and crumble, Porras-Kim succeeds in challenging the exhibiting institution to act against conservation interests in order to fulfill the artist’s intent: decay. The ephemerality of the sculpture chips away at the concept of ownership based on permanence and suggests—as a potential model for the ethnographic museum—thinking of cultural stewardship instead as a process, one “subject to unexpected change” and even erosion.4

In her book, The Metabolic Museum, Clémentine Deliss identifies the museum “as a complex body with a severely ailing metabolism, afflicted organs, and blocked channels of circulation.”5 To transform this condition in order to heal the museum, Deliss argues, will require careful nurturing but also radical operations. Part of this work will involve exhuming objects from the vaults and placing them at the forefront again, making corrections to notions of modernity and classification, and bringing in alternative models of display that challenge museums’ sole custody over looted collections. In practice, this involves a constant process of negotiation with existing structural forces that are difficult to reverse or even challenge, particularly when museums’ ties to colonialist collecting practices are sealed off, and with them “the individual identities and intellectual property rights of the artists, designers, and engineers whose works they acquired or looted.”6 Porras-Kim uses the language and institutions of contemporary art to address this erasure. Rather than idealize the restitution of human remains and sacred objects (which even when successful does not constitute a full restoration of an object’s original context and function), the artist is interested in interrupting knowledge systems that seek to immobilize through acquisition, classification, study, and display.

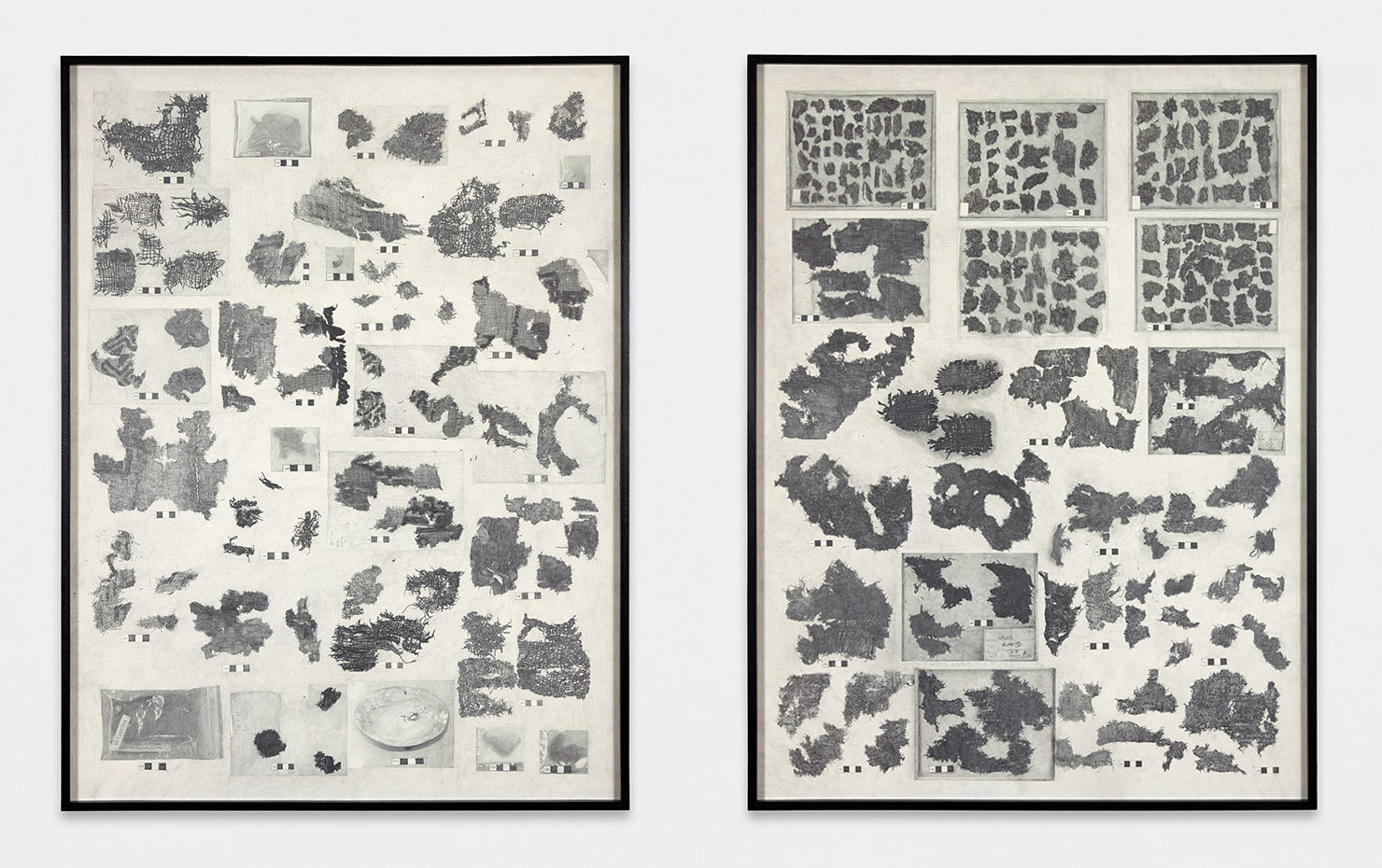

Offerings for the Rain at the Peabody Museum (2021) comprises a series of seven large square framed drawings, each featuring a colorful array of objects reproduced from the Peabody Museum’s sacred cenote collection. They are depicted on horizontal shelves according to color, size, or maybe simply aesthetic preference. Porras-Kim applied a similar treatment to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Proctor Stafford collection in 2017 to highlight the subjectiveness of institutional systems of classification. Here again, jade necklaces, earth-toned ceramic vessels, and polished gold bowls are reproduced in colored pencil with such a forensic attention to detail that they seem to supersede their status as objects and retrieve their spiritual dimensions. Porras-Kim’s time-consuming act of reproducing the images with pencil “crystallizes the encounter between the artist, the objects, and the lives the objects have touched and continue to touch.”7 As Kee observes, “Drawing… has its own duration, which attaches maker and subject in a way that opens onto a different sociality.” In collecting the collection anew through the practice of drawing, Porras-Kim breathes presence back into the artifacts and restores consciousness to the makers whose wishes for the afterlife have been obfuscated and even denied. The work does not remedy the omissive histories of these largely looted goods and their ongoing absence in locations of origin. To do so would be a task predicated on impossibility. What it does do is motivate us to imagine another side to their position in history, signaling that the legal hold on collections by a museum cannot control the potential meanings and narratives generated.

Open House: Gala Porras-Kim, installation view, MOCA Grand Avenue, October 7, 2019–May 18, 2020. Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo by Jeff McLane.

In Asymptote Towards an Ambiguous Horizon (2021), twelve graphite drawings depict the ground location of Göbekli Tepe, a Neolithic UNESCO World Heritage Site in present-day Turkey, as it stood in 2020, beneath changing projections of how the south-facing sky looked 12,000 years ago. The present-day site and the 12,000-year-old sky approach one another on the horizon, but they never meet, forming curves toward an asymptote, or a hybrid landscape where prehistory coexists with contemporary attempts to reconstruct it. Drawing emerges again as a way for the artist to form intimacy with a site we are now so far removed from, a meditative and almost spiritual practice aimed at reinscribing the possibility for that which we may never know within the regimes of the ethnographic museum.

Alongside Porras-Kim’s drawings, an audio track alters and rearranges the basic elements of the temple’s “discovery” story. Against a backdrop of howling wind, accounts from archaeologists, astronomers, and concession stand owners collide and collude with one another, jeopardizing a singular, authorized account of the story of the monuments. By opening up the possibility for uncertainty and multiple points of view, the hierarchy of discourse promoted by the ethnographic museum begins to topple. Viewers are empowered to imagine additional, nonexclusive interpretations, not only for the site at hand but also for meaning making more broadly.

Porras-Kim’s interest in what Deliss calls “ambiguous objects,” or objects that cannot be fully encompassed or understood within the museum’s systems of knowledge, has interesting implications for site-specificity and artistic intent in the context of modern and contemporary art. In 2019, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, invited Porras-Kim to curate one of its Open House series. She selected objects in the collection that were decaying, were made to expire, or existed in a legal limbo between their maker’s intent and their inclusion in an institutional context. Among these were a Margaret Honda sculpture confined to storage due to a safety concern; a single, spare fluorescent lightbulb for a Dan Flavin piece that was emphatically catalogued as not a work of art; and the battered, splintered remains of a piano that artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz shattered at the museum four decades prior. This last object had been part of one of the many iterations of the performance Henny-Penny Piano Destruction Concert (1966–98), after which it was acquired by MOCA and somewhat arbitrarily classified as a sculpture within its collection. In the lead-up to the exhibition, Porras-Kim initiated a series of negotiations on behalf of Montañez Ortiz to change the work’s object file, which eventually resulted in the new and unique category of “destroyed piano” and the additional condition that MOCA accompany any display of the piano with documentation of the original performance.

Left to right: Gala Porras-Kim, 203 offerings for the rain at the Peabody Museum, 2021. Graphite and ink on paper, 47 × 35 1/2 in. (framed: 48 1/2 × 36 1/2 × 2 in.); 70 offerings for the rain at the Peabody Museum, 2021. Graphite and ink on paper, 47 × 35 1/2 in. (framed: 48 1/2 × 36 1/2 × 2 in.). Courtesy of Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

Though the work’s reclassification may feel like splitting hairs (as so much is within institutional settings), the curatorial project speaks to Porras-Kim’s hope that collecting be understood as an ongoing labor of care in accordance with the maker’s intent. Of course, when the people who should be consulted are no longer alive, negotiating what would be appropriate systems of classification and display is a trickier process. Take Porras-Kim’s contribution to the 2020 Gwangju Biennial, A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2020), which was shown at the Los Angeles gallery Commonwealth and Council concurrently with Porras-Kim’s Amant exhibition. In the work, Porras-Kim considers the active afterlife of a body from the first century B.C. housed in the collection of the Gwangju National Museum in South Korea. The artist attempts to contact the spirits of the dead and ask them to manifest a preferred resting place for their remains through her own version of encromancy, an ancient form of divination using the patterns of ink formed on a sheet of paper. Though the resulting swirls of blues, greens, oranges, and reds are indecipherable to the artist herself—let alone a general audience—they encourage the viewer to imagine alternative practices of care for objects that fall outside of institutional norms.

A terminal escape from the place that binds us reveals how the collecting, preserving, studying, and displaying of human remains put spiritual, legal, and museological norms into direct conflict. In conservator Sanchita Balachandran’s words, “human remains confound simple categorization” between individuals, objects, and works of art, “making discussions on their appropriate and respectful care uncomfortable and contentious.”8 Even the category of “human remains” is vague, inconsistent, and does little to honor the intangible traces of a human life and its afterlife.9 Little was known about the body at the Gwangju Museum other than its likely provenance from Shinchang-Dong, Gwangju, which made it difficult for anyone, including Porras-Kim, to negotiate on their behalf. A terminal escape from the place that binds us wrestles with the challenges of reversing the ossified structural forces that transform corpses into commodities and lives into property. Rather than proposing a poetic unknowing of what the body would have wanted, the striations and swirls of ink map how immaterial histories can constitute part of ethnography today. Like Asymptote Towards an Ambiguous Horizon, this project hinges on uncertainty and non-linearity, and it problematizes the lack of context and history that is afforded by the institution.

Gala Porras-Kim, A terminal escape from the place that binds us, 2020. Ink on paper, document, 73 × 96 × 2 in. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

The care of human remains is the subject of another work at Amant, titled Leaving the Institution Through Cremation Is Easier than as a Result of a Deaccession Policy (2021). Here, Porras-Kim reformulates the question of what bodies the museum legitimates into the one Paul B. Preciado poses when he writes of the necropolitical constitution of the museum: “What bodies can the museum legitimate?”10 When a fire in 2018 devastated the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro, among the nearly 20 million objects destroyed were the remains of Luzia, the skeleton of a young woman who is believed to have died sometime between 11,243 and 11,710 years ago, making her remains the earliest evidence of a human population in the Americas. The highly publicized case involved the circulation of images of Luzia’s fragmented skull—cracked and damaged by the fire—and public statements made by museum staff who said they were confident that it could be reassembled with information obtained through DNA testing.

Far from unique, Luzia’s case evidences the merging of biomedicine with ethnography. It speaks to what Zoé Samudzi describes as the “necrophiliac impulse” of the museum, which “governs the long-standing practice of excavating, proudly displaying, and fiercely protecting claimed ownership over (and crudely disposing of) the bodies of the racialized dead.”11 Animated by cultural anxieties over mortality and legitimized by the Western regime of property rights, the necropolitical colonial museum survives by alienating some subjects from full humanity, dispossessing them of agency, native land, and their own bodies. Deliss draws a parallel between the practice of extraction in the field of art and the “illegal safaris of organ hunters,” where “the human body is usurped, dismembered, and traded under the radar, circulating between the criminal world of traffickers, impoverished donors, sick recipients, and unscrupulous medical staff.”12 Coupled with the increase of biomedical research in ethnographic museums, human remains are overwhelmingly treated solely as objects of study—their humanity undermined by invasive conservation practices that impede the ritualization of death. When we so readily compromise an object’s physicality for the sake of research (like the common practice of taking scrapings for lab analyses or the performance of magnetic resonance imaging on artifacts believed to be of religious significance), why, then, are we so hesitant to preserve its immaterial qualities—its spiritual significance and connection to the afterlife?

Gala Porras-Kim, Leaving the Institution Through Cremation Is Easier than as a Result of a Deaccession Policy (details), 2021. Left: Letter addressed to Mr. Alexander Kellner, Director of the National Museum of Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Los Angeles, July 31, 2021; right: napkin and ash. Courtesy of Amant. Photos: Shark Senesac.

Leaving the Institution Through Cremation Is Easier than as a Result of a Deaccession Policy, Porras-Kim’s framed letter to Alexander Kellner, Director of the National Museum of Brazil, suggests that care would mean treating Luzia as the cremated body of a person rather than an object to be studied. On display, a delicate piece of tissue holds a handprint made with ash from the fire. It is an object of mourning, the tissue paper dually acting as a vessel for tears and a cinerary urn for Luzia’s remains. The work is equally forensic and ephemeral, possessing a pseudo-indexical quality similar to the Shroud of Turin, the sheet whose rust-colored imprint of a face is widely believed to belong to Jesus of Nazareth. More important than the question of to whom the handprint belongs is how it situates the museum as a cemetery—a very poor one. As Samudzi writes, the exhuming of buried bodies and their permanent maintenance is a disruption of death, violating the sanctity of the burial and preventing ancestralization and proper transition.13 The handprint is accompanied by Porras-Kim’s not-so-radical proposition for museum officials: Don’t reconstruct Luzia. Incinerate the rest of her remains and allow her to return to dust. The fire already challenged Luzia’s ability to exist purely as a historical object; letting her body decompose would be a small but necessary step toward repair, toward the simple realization that some things are not meant to exist forever.

In Forecasting Signal (2021), on view at Commonwealth and Council, condensed moisture from a dehumidifier drips onto a burlap sack primed with graphite powder, causing beads of black ink to trickle onto a white canvas. This sculpture could be a kind of oracle, divulging its prophecy in washes of stain, just as the drips of black ink could feign sweat, tears, blood, or any of the other traces of human presence that are sanitized away in the climate-controlled storage facilities of museums. It speaks to the fact that bodies will generate meaning even under excessive structures of confinement, just as they will continue to break down and turn to dust, despite our most fastidious efforts to conserve them. To recognize this process as part of an entangled cycle is to disrupt the symbolic “us” and “them” distinction on which museums are founded.

Gala Porras-Kim, Forecasting Signal, 2021. Burlap, liquid graphite, ink, ambient water, panel, dimensions variable. Installation view, A terminal escape from the place that binds us, Commonwealth and Council, November 6—December 18, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

The dust in Precipitation for an Arid Landscape similarly blurs the illusion of coherent boundaries between personhood and objecthood. It connects the bodies moving through the space in the present and the past, in a way giving agency back to those rendered immobile by ethnographic interpretations. In an early conversation about the work, Porras-Kim described the reunion of dust with rain as an act of “spiritual repatriation.”14 This characterization may be a scoff directed at the recent phenomenon of “digital repatriation,” wherein museums issue digital surrogates of artifacts in lieu of returning them physically to their cultures of origin. The importance her own gesture places on objects’ cultural and spiritual import doesn’t attempt to be a fix-all for the injuries of the past, but it does begin to call into question the limits of existing paradigms that disregard these qualities altogether. The failure to care for archeological objects whose makers and owners were afforded few or no legal rights seems inevitable, given these limits.

We emerge from the encounter with a sense of incompleteness, with the troubled recognition that the work of undoing our ongoing ethnographic present is never done.

Mariana Fernández is a writer and curator living in New York.