1. Combustion

Combustion is the hidden principle behind every artefact we create. …Like our bodies and like our desires, the machines we have devised are possessed of a heart which is slowly reduced to embers.

—W. G. Sebald1

In the early hours of December 6, 2017, a fire broke out in the dry brush of a canyon close to the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. The blaze moved rapidly down the Sepulveda Pass close to the 405 Freeway, and by the time morning traffic started to build a few hours later, the hillsides to the east were extensively burned. Trees and scrub were reduced to embers glowing in the morning gloom as walls of flame raged along the freeway’s edge. Incredulous drivers recorded the apocalyptic scene on camera phones as they drove by. Soon after, the freeway was shut down and evacuations began in the surrounding neighborhoods.

A mile farther down the smoke-filled canyon, on the other side of the freeway, administrators at the Getty Center decided that the museum would not open its doors that day. Later, a spokesman expressed concern for the museum’s neighbors but reassured the public that the museum itself was not in any danger. Laying out the Getty’s defensive precautions, he made it clear that there was no prospect of evacuating their collections: The vegetation around the site was carefully maintained to shield it from encroaching wildfires; the structures themselves were made from non-flammable materials—steel, glass, marble—and should a fire need to be extinguished, the Getty possessed a reserve tank containing a million gallons of water. “The safest place for the art is right here,” he said. It might seem like stating the obvious, therefore, to say that the Getty stood, literally and figuratively, against the conflagration that bore down on it that December day, its physical infrastructure a bulwark against the explosive threats posed by the landscape. Internally, too, the museum appears to stand against the ravages of the physical environment, those that the Getty’s conservators and archivists are so expert at thwarting: the menace of heat, moisture, dust, bright light—altogether the slow entropic decline of its collections through time. Seal it up and keep it safe, such is the archival function of museums.

Firefighter Bobby D’Amico looks over the Getty Center while monitoring the scene over Bel-Air, where the Skirball fire has destroyed several homes, December 13, 2017. Copyright © 207. Los Angeles Times. Photo: Brian van der Brug.

Yet the Getty’s relationship to its own devastation is far from straightforward, in spite of its implacable façade. The sobering reality of any institution, no matter how monumental, is that time and entropy will inevitably win out in the end, even if out-and-out catastrophe does not intervene. The institution’s attempts to halt the destructive effects of nature on its collections, its library, and its archive are ultimately futile. As Hal Foster observed, “Any archive is founded on disaster (or its threat), pledged against a ruin it cannot forestall.”2 The great ancient Library of Alexandria, he points out, burned numerous times before its final complete destruction. The National Museum of Brazil, founded in 1818, was recently gutted by a fire that destroyed almost its entire collection.3 Perhaps the Getty’s very existence is predicated on potential disaster.

This, then, is a story of the potentiality of destruction, as well as its threat, a condition we find echoed in ancient tradition. In Roman myth, Giants opened a forest clearing with the aid of Vulcan, the god of fire, in order to see bolts of lightning as they crossed the sky, reading these as auspices sent by Jove. The burnt clearing was a place where meaning emerged, in other words, a place of contemplation.4 For some cultures, moreover, proper stewardship of the land involves carefully managing this cycle of destruction and creation in order to make the environment habitable. The Native peoples of the American Southwest have known for millennia how to use the power of fire to shape the landscape and maintain its balance, using low intensity burns to create manageable, livable environments and prevent larger, more destructive fires. Clearly, then, there is an ethical dimension to all of this. If combustion is a principle, to use W. G. Sebald’s term—a beginning—how that principle is enacted can have enormous consequences, sometimes beneficial, sometimes cataclysmic. Humanity’s technological and territorial expansion has tended toward the latter, accompanied as it has been by the burning of vast forests either to create usable agricultural land or in the manufacture of resources and commodities—timber, sometimes, or charcoal used in the iron smelting process. Thus, catastrophic fires make space for progress and empire, for better and for worse.

2. Suspended Animation

The beginnings of the new always take place in chaos.

—Joseph Beuys5

These Manichean reflections on the interdependence of creation and destruction struck me in the aftermath of two recent exhibitions exploring the legacy of the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann (1933–2005). The first, Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions, was a survey at the Getty Research Institute; the other, Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, recreated an exhibition from 1974. Szeemann himself was very adept at conjuring meaning from the residue of destruction, as exemplified by the show that announced his career to the world at large, Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, which featured extensively in the Getty’s exhibition. When Attitudes Become Form, staged in the spring of 1969, was incendiary in a theoretical sense, featuring an international group of provocative post-minimalist and conceptual artists; it was also more literally so, involving the actual destruction of parts of the museum that hosted it, the Kunsthalle in Bern, Switzerland. On a small scale as well as a large one, Szeemann’s artists tore up the fabric of the institution in order to reshape its meaning. Lawrence Weiner, for example, chiseled off the plaster from a 36-by-36-inch section of gallery wall, while, more dramatically, Michael Heizer, as though taking his groundbreaking remit literally, demolished the pavement outside the museum with a wrecking ball, leaving behind a large, irregular crater in the asphalt. The presumably bewildered, provincial Swiss audience faced with this exhibition could be forgiven for seeing in its contents—a brief sampling of which also included piles of thick grey felt, flaming torches suspended above a mound of cement powder, and an igloo made from panes of glass—only a chaos of objects and processes, seemingly assembled at random. If, indeed, they could find their way into the galleries at all. During an exhibition the previous year, it was not clear to potential visitors that the museum remained open at all, Christo having wrapped the whole building in plastic sheeting.

Michael Heizer demolishing the pavement outside the Kunsthalle Bern as part of Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, Kunsthalle Bern, March 22– April 27, 1969. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2011.M.30). Photo: Balthasar Burkhard.

Christo, Wrapped Kunsthalle in 12 Environments: 50 Jahre Kunsthalle Bern, 1968. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2011.M.30). Photo: Balthasar Burkhard.

For the artists themselves, however, and for Szeemann, this destruction was a condition that allowed new meaning to emerge, a clearing, like that of the mythical Giants, where the clear-sighted could gain knowledge. Emblematic in this respect is Water De Maria’s contribution to When Attitudes Become Form, titled Art by Telephone (1967), which consisted of a black rotary dial telephone placed in the middle of the gallery floor and accompanied by a typed note explaining, in English and German, “If this telephone rings, you may answer it. Walter De Maria is on the line and would like to talk to you.” Throughout the duration of the exhibition, De Maria called the gallery a handful of times from his New York studio (sometimes, because of the time difference, in the middle of the night when the gallery was closed). Besides this, the telephone stood dormant. De Maria’s work dispensed with the preconceptions of what an artwork should consist of. Instead, it presented an elegant idea: a way of thinking about authorship that emphasized how tenuous and discontinuous the communication between creator and audience can be; at the same time, Art by Telephone drew attention to the potential moment of connection that brought the dormant system back to life.

Walter De Maria, Art by Telephone, 1969. Installation view, Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, Kunsthalle Bern, March 22–April 27, 1969. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2011.M.30). Photo: Balthasar Burkhard.

In an interview during the installation of When Attitudes Become Form, Lawrence Weiner expressed a similar view that his work held a potentiality that defied its physical existence. Describing the idea behind his work A 36″ x 36″ Removal to the Lathing or Support Wall of Plaster or Wallboard From a Wall (1968), he commented on the various manifestations that the work could potentially take. It could be recreated, he claimed, “in your home. You can live with it. You can also keep it in your memory for the rest of your life. Wherever you move, you can build this yourself and you have it for your entire existence. It’s not a precious, unique object…but an idea that has fifty, sixty, hundreds of representations. And each time, it’s new. …You cannot lose it, you cannot destroy it. It’s there forever.”6 Weiner’s work therefore embodies a condition that exists in many of the works championed by Szeemann: the potential of physical destruction to generate a store of ideas held in suspended animation, awaiting reawakening. Yet there exists a tension here, a sense of loss that comes from the absence of physical properties Weiner describes. For all the advantages of the work as idea—its durability, its reproducibility—destruction causes the loss of qualities we also value—preciousness and uniqueness. These are the qualities of physical immediacy we find reassuring in the world around us, those that we mourn when they are absent.

Lawrence Weiner making his piece in Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, Kunsthalle Bern, March 22–April 27, 1969. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2011.M.30). Photo: Harry Shunk.

For the writer W. G. Sebald, who considered the implications of the cycle of creation and destruction throughout his work, the paradoxes of this notion were everywhere apparent. Sebald prefaced his novel The Rings of Saturn with an epigraph taken from the Brockhaus Encyclopedia that provides a metaphor for his literary approach: “The rings of Saturn consist of ice crystals and probably meteorite particles describing circular orbits around the planet’s equator. In all likelihood these are fragments of a former moon that was too close to the planet and was destroyed by its tidal effect ( —> Roche limit).”7 The Roche Limit alluded to here refers to the nineteenth-century astronomer Édouard Roche, who first speculated about the formation of Saturn’s rings in this manner. Roche calculated the space where tidal and gravitational forces hold each other in check, maintaining a precarious balance. Within this limit, the annihilated remains of the moon are held suspended, forming the planet’s most distinctive feature. Typically saturnine itself, Sebald’s writing was likewise constructed from the remnants of previous disasters. The Rings of Saturn is pulled together from the fragmentary accounts of neglected episodes in modern history and are often linked to the devastation wrought by the march of civilization—the Holocaust, the horrors of the colonization of Africa. As Eva Hoffman put it in 2002, the central themes of Sebald’s novels are “the sources of the catastrophic imagination, the continuities between human nature and nature, and the inexorable interweaving, within both, of desire and destruction, pattern and chaos, proliferation and decay.”8 Sebald shows us the way destruction works through history, the way the horror and injustice of a particular moment are held in fragmented, suspended animation, forming the physical and emotional raw materials for subsequent generations.

Harald Szeemann’s archive functions according to this same principle of suspended animation. A sprawling presence that forms the backdrop to the Getty’s Szeemann exhibition, the archive seems to constitute the structuring mechanism of the curator’s work. The Getty Research Institute acquired the archive in 2011 and moved it, over a period of years, from its original home, in a former watch factory in the town of Maggia, Switzerland, to Los Angeles. The Szeemann archive was sheltering in the rarified, climatecontrolled air of the GRI that fiery day in 2017, imperiled and protected simultaneously. The GRI exhibition comprised a welter of material culled from it: books, letters, interviews, notes, and other sources from which Szeemann drew together his ideas, as well as photographs and artefacts that document the exhibitions that he curated.9

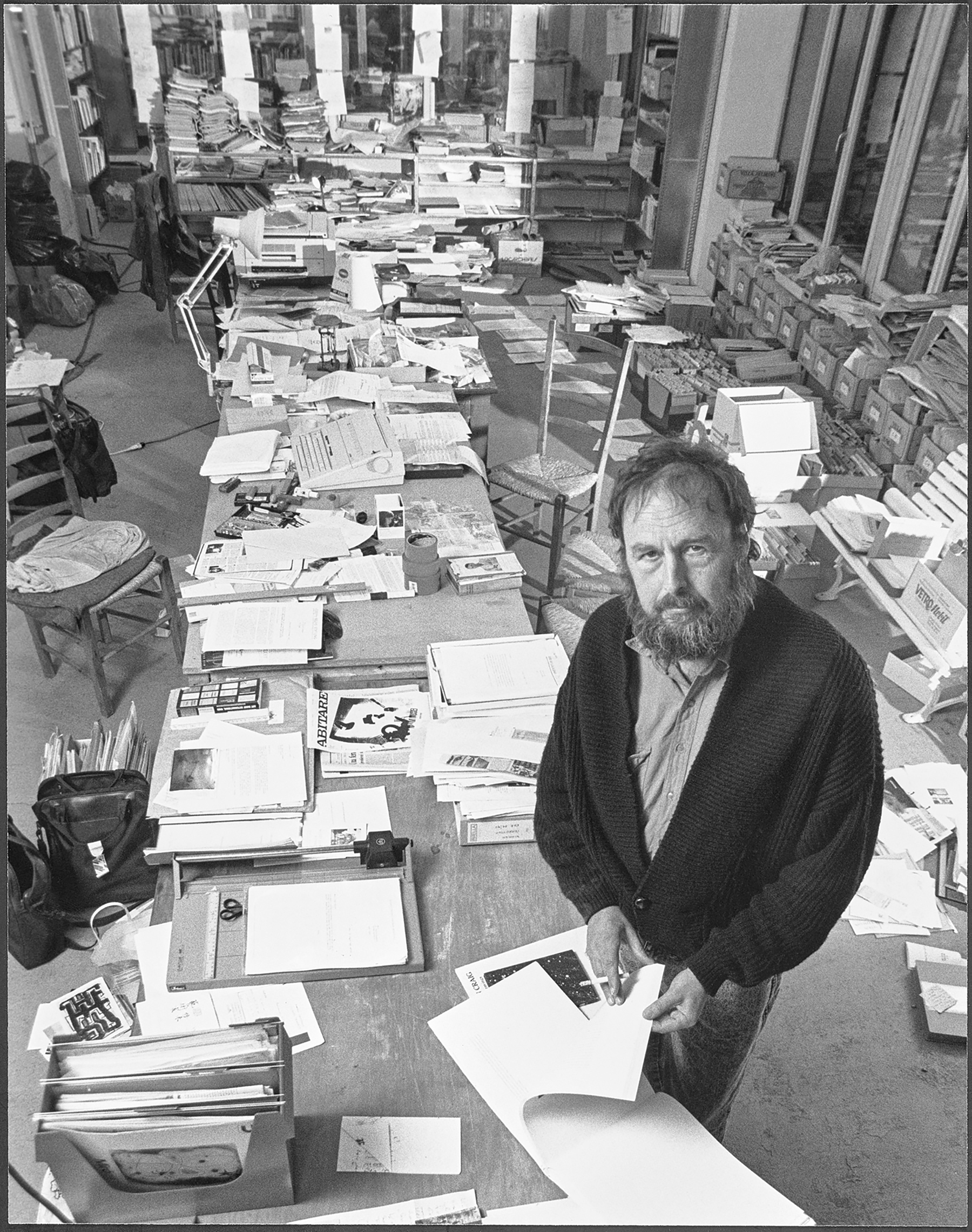

Szeemann referred to this archive as the Fabbrica Rosa—the pink factory—and it is easy to see how it was both the mechanism and the product of his curatorial process.10 The mountain of material Szeemann amassed, almost all of which ended up in his archive, was an index of his experiences traveling to meet artists around the world, conversing with them, corresponding with them, and collecting texts and objects relating to their practice, from which maelstrom order was finally salvaged and exhibitions staged. In one way, of course, this is simply a long-winded way of saying Szeemann was a curator, but in his case the contrast between the chaos of the archive and the clarity of his authorship is stark. “I am not a curator,” he claimed in 1997, “I am an author.”11 Images of Szeemann in the Fabbrica Rosa before his death in 2005 show him diligently working amidst orderly disarray—books and files line the walls around him, every surface covered with paper, notes, folders, and objects. Available wall space is taken up with Post-It notes and other tacked up material, evidence of his recent activities and future projects. At various times during Szeemann’s career, the ever-increasing accumulation of material was split between a number of residences before he gathered it together in Maggia. This massive collection was the vertiginous morass over which he fought his intellectual fight—Szeemann’s own rings of Saturn.

Harald Szeemann’s address list of New York-based artists (verso & recto), n.d. Color ink on paper, 11 9/16 × 8 3/16 in. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2011.M.30).

The archive as a broader concept has been much theorized, but its vast scale and the multiplicity of its possibilities—the qualities so evident in Szeemann’s archive—are central to Jacques Derrida’s “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” an abstruse meditation on the influence of the Freudian death drive on the theory of Deconstruction. In spite of its difficulty, this text provides us with a set of analogs for the process of destruction and recreation that takes place around the archive. Derrida, by foregrounding Freud’s death drive, supposes an instinct towards self-destruction that he regards as fundamental, not just to the individual psyche but also to the archive, the law, and the functioning of history. Linking the archive and the individual psyche—as history and memory respectively—Derrida notes the interdependence of destructive and generative forces in both. He claims that to be en mal d’archive (to suffer from the titular “archive fever”) means “to burn with a passion. It is never to rest, interminably, from searching for the archive right where it slips away. It is to run after the archive, even if there’s too much of it.”12 Derrida’s wider intention in interrogating these ideas was to trace the connections between authority, law, and the archive, to say something about how the nature of the psyche can be traced in the functioning of government. In order to do this, he locates the origins of the concept to the Greek arkheion, literally the home or dwelling in which official state documents were kept under the care of a presiding magistrate. Derrida is keen to show that, right from the outset, the idea of the archive was a place of seeming authority and security but also a place of effacement or destruction, a place where memory and meaning break down.

Harald Szeemann in the Fabbrica Rosa, his office and archive, Maggia, Switzerland, c. 1990s. © State Archive of Canton Bern. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2011.M.30). Photo: Fredo Meyer-Henn, State Archive of Canton Bern.

Such effacement is certainly evident in Szeemann’s attitude to his archive, which he regarded as continuous with his personal history, even his own memory: “My archive is my memoir,” he commented, “Too bad I cannot walk through it any more. It has become so full. Like Picasso I would like to close the door and start another.”13 One senses that at some point the aggregate of the archive became overwhelming for Szeemann, its countless human fragments an impenetrable concretion in which, as Derrida puts it, “order is no longer assured.”14 But like Derrida’s archive, and like memory, meaning emerges from this disorder, its fragments pulled together to form new ideas. Even old memories are reconstituted out of the debris from which they were originally made, just as new exhibitions emerged from Szeemann’s chaotic researches.

3. Rekindling

Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.

—Walter Benjamin15

Szeemann was never pessimistic in his assessment of the outcomes of human endeavor, but there is the sense throughout his work that countervailing forces are at play within it, threatening the destruction of meaning at one moment and offering up the possibility of creation the next. The tension between order and disarray is nowhere more palpable than in the exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us, which presents us with a mass of seemingly trivial and contingent historical objects that, nevertheless, Szeemann was at pains to arrange in order to achieve the desired effect. On the face of it, the exhibition is a tribute to, and a memorial for, Szeemann’s grandparents, focusing particularly on the life of his late grandfather, Étienne Szeemann, a successful and innovative hairdresser in early-twentieth-century Bern. Describing the exhibition’s inception, Szeemann explained that when his grandfather died, in 1971, he collected the objects that reminded him of his grandparents and began planning an exhibition based on these possessions. Szeemann evidently identified with his grandfather, with whom he seems to have had a lot in common, particularly his accumulative tendencies. As Szeemann wrote, his grandfather was “a passionate collector (of professional documents, stamps, engravings, badges, shooting target cards, emergency currency). His apartment at Ryffligässchen 8 was a classic example of an overfilled lodging.”16 From all this material, which the Grandfather exhibition gravely lays out for our inspection, we get an impression of Szeemann’s family history as a tangle of exploded fragments, from which each visitor is encouraged to salvage the vestiges of meaning.

Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us (1974), installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, February 4–April 22, 2018. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us (1974), installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, February 4–April 22, 2018. Photo: Brian Forrest

Szeemann staged the 1974 exhibition in his own apartment in Bern, and the current exhibition presents a life-size mock-up of this original space, with drywall hung on a framework of aluminum studs. The temporary structure stands starkly in the middle of the ICA’s large main gallery. There is a peculiar Russian-doll effect to recreating an exhibition that was itself a recreation of another space—Étienne’s apartment, nesting inside Harald’s apartment, nesting inside the ICA—that makes it difficult to tell in relation to these places exactly when and where we stand. Similarly disorienting is the way its space dilates, starting in the confines of a winding hallway hung with Szeemann’s grandparents’ possessions, then opening out into a bedroom similarly adorned, and finally moving into a space displaying artefacts from Grandfather Szeemann’s hair salon: razors, trimmers, curlers, bottled tonics, wigs, etc., etc., etc. Adding to this bewildering feeling of temporal and geographic displacement, Szeemann presents relics from his grandfather’s professional life with solemn reverence alongside the accoutrements of his everyday existence, some banal, some eccentric—framed prints, solidly made furniture, a stuffed Chihuahua. Adjacent to a wall papered with countless fashion plates illustrating modish ladies’ hairstyles of the 1920s sits an extraordinary recreation of an eighteenth-century pompadour hairstyle featuring a silver model of a French naval frigate atop thick, wave-like curls. The bewigged mannequin admires her own Rococo splendor in the mirror before her, and Szeemann, with a Duchampian flourish, balances this extraordinary object on top of a four-legged stool.

Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us (1974), installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, February 4–April 22, 2018. Photo: Brian Forrest.

In spite of its strangeness, perhaps even because of it, the environment Szeemann creates in the Grandfather exhibition has a distinctive atmosphere that seems authentically to belong to the past, albeit a past whose timeframe shifts constantly before our eyes. One of the most perplexing aspects of this condition is the extent to which it allows its visitors not only to inhabit a number of different times and viewpoints within the Szeemann genealogy, but also to insert ourselves into it. For me, this meant that I began to find the objects within the exhibition remarkably redolent of my own past, in spite of the fact that they have nothing, objectively, to do with me. Szeemann’s grandparents’ chenille coverlet, for example, placed on a bed in a recreated bedroom, generated a nostalgic feeling I found powerfully evocative of my childhood. (By way of contrast, an object I own that actually belonged to my grandparents, a music box in the shape of an Alpine chalet, which they acquired on a trip to the continent in the 1960s and which stood on their mantelpiece through all the years I knew them, now removed from this original setting holds few memories for me, much to my chagrin.) In a semiotic context, this might be obvious: objects, like words in a language system, depend on their relation to others to give them meaning. But this condition is rarely so vividly demonstrated as it is here, amplified by the dynamics of memory that swirl around the exhibition.

Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us (1974), installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, February 4–April 22, 2018. Photo: Brian Forrest.

The Grandfather exhibition can therefore be seen as an examination of how the events of one era seep into those that come after. In spite of the destructive cycle of combustion and regeneration that constitutes history, certain ideas endure. Thus, the lives of the European bourgeoisie, of which Étienne Szeemann was a proud member, were inextricably linked to the greatest human tragedies of the modern world. As a product of the postwar period, Harald Szeemann was acutely aware of the continuum between the grand narratives of the age and their catastrophic fallout. For his generation, the disasters of twentieth-century European history could be felt in the trivialities of everyday existence, even in the silences that masked the repressed truths of recent history. Moreover, for some who collaborated with Szeemann on his exhibitions, the urgency of this cyclical regeneration was by no means purely theoretical. Eva Hesse, for example, fled Nazi Germany in 1938, evacuated at the age of two from Hamburg on one of the last Kindertransport trains to Holland. Many of the family members she left behind perished in the Holocaust, and her mother, who escaped later, never got over this trauma and committed suicide in 1946, as the full horror of the death camps emerged in the press. Hesse carried this devastation with her. Her work, in common with other Szeemann artists, attempted to efface the aesthetic conceptions of previous generations, but continued to manifest the pain and suffering that preceded it.

Throughout the exhibition, therefore, we get hints and echoes of the destructive forces of European history: Étienne’s proud nationalism evoked, rather bizarrely, in a piece of felted fabric bearing the Swiss flag and made from the dyed scraps of human hair collected from his salon, and framed prints depicting various colonial ventures in North Africa and South America. One of these prints shows the Chief of the Aimoré people of Brazil with his wife and children striding across a forest clearing, distinctive wooden discs worn in their distended lower lips. The Aimoré inhabited the forests of southeastern Brazil, where European settlers attempted to eradicate them by poisoning their food and deliberately introducing lethal smallpox.17 These forests were prized for their Brazilwood, the paubrazil, as the Portuguese settlers called it, which ultimately lent its name to the country. Brasa means ember in the Latin, and paubrazil was characterized as “red like an ember” on account of its intensely red heartwood, a horrifying foreshadowing of the deforestation through slash and burn that ravaged Brazil throughout its colonial period and reached it apogee in the late twentieth century.

Elliptically, then, we return to the opening theme of this essay—fiery destruction. Disaster and death, it seems, endure in the aftermath of the scenes of devastation, even when the materials of subsequent creativity are generated by these means. The ghosts of the past remain, preserved in suspended animation within the fragments of the archive. Glenn Phillips, co-curator of the GRI exhibition, was involved in the Getty’s acquisition of the Szeemann archive from the beginning. He writes in the exhibition catalog about the chaotic state in which he found the archive in 2010: “Szeemann had kept everything that came his way, and each new project served as an occasion to expand his collections into new areas and themes. The physical chaos around us was the relic, left largely intact, of an active office led by a voracious intellect. There was still a lingering feeling that Mr. Szeemann might walk through the door at any moment, returned from another long trip, but it had been five years since his death. The dust had settled thickly.”18 The space of the archive, in its chaotic, dusty entropy, remained a place of potential. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

Jon Leaver is Professor of Art History at the University of La Verne. His research focuses on nineteenth-century art and criticism as well as the contemporary art of Los Angeles. Leaver is a member of X-TRA’s Editorial Board.