When I first met Susan Mogul in 2010, we commiserated about her tough negotiation with her mother who was downsizing to a small apartment. She showed me stacks of her mother’s powerful black-and-white photographs, taken over much of her adult life. Rhoda Blate Mogul maintained a small basement darkroom where she worked late into the night while her husband and six kids slept. Back when we spoke, Mogul had already begun to gather material for her “Mom movie” and for another project, A Daughter’s Survival Index, to contend with the legacy of things amassed by her mother, a savvy bargain huntress with a penchant for mod fashion and mid-century modular furnishings, traits she had passed onto Mogul, her eldest.

While A Daughter’s Survival Index is unrealized to date, Susan Mogul included items from it in Less is Never More, her recent exhibition at as-is.la. Full yet not overstuffed, Less is Never More consisted of self-produced posters and shopping bag prototypes; a selection of furniture and apparel she purchased or inherited from her mother; and an arrangement of postcard-sized prints of cultural objects and ephemera, stills from the artist’s performances and videos, and photographs taken by Rhoda Mogul. This show was complemented by an offsite screening of Mom’s Move (2018) at the Echo Park Film Center. Mogul’s straightforward twenty-five-minute documentary, both piquant and affectionate, honors Rhoda Mogul’s practice as an amateur photographer and their relationship as mother and daughter while capturing the process of the two sorting through a life’s accumulation of possessions in anticipation of the sale the family home in Long Island, New York, in 2012.

Susan Mogul, Mom’s Move, 2018. Film, 25 min. © Susan Mogul. Limited Screening available here until September 30, courtesy of the artist and Video Data Bank..

The main gallery of as-is.la was organized like a typical cultural history display or the kind of tastefully arranged retail experience trending online. In a wall text, Mogul called her exhibition “a memoir disguised as a showroom.” Placed on low white plinths were worn but clearly well-maintained mid-century and modernist-inspired chairs, including a 1949 Herman Miller LCW Chair by Charles & Ray Eames that features prominently in the storyline of Mom’s Move. The tags for stylish vintage clothing mounted on walls were branded “MOGUL” and carried the exhibition’s signature image: a self-portrait of a pregnant Rhoda Mogul in profile, wielding an SLR camera while seated in a rocking chair. There is something dynastic in this image, which was taken in a photo shoot staged in Mogul’s bedroom when she was an adolescent and her mother was near full term with another child. The branding also served in publicity announcements for the show and screening. In another era, Mogul’s fusion of the personal and mercantile might have come off as idiosyncratic. Today, however, “influencers” are everywhere and we have become habituated to such conflations.

Susan Mogul: Less is Never More, installation view, as-is.la, Los Angeles, August 4–September 8, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and as-is.la. Photo: Julie Shafer.

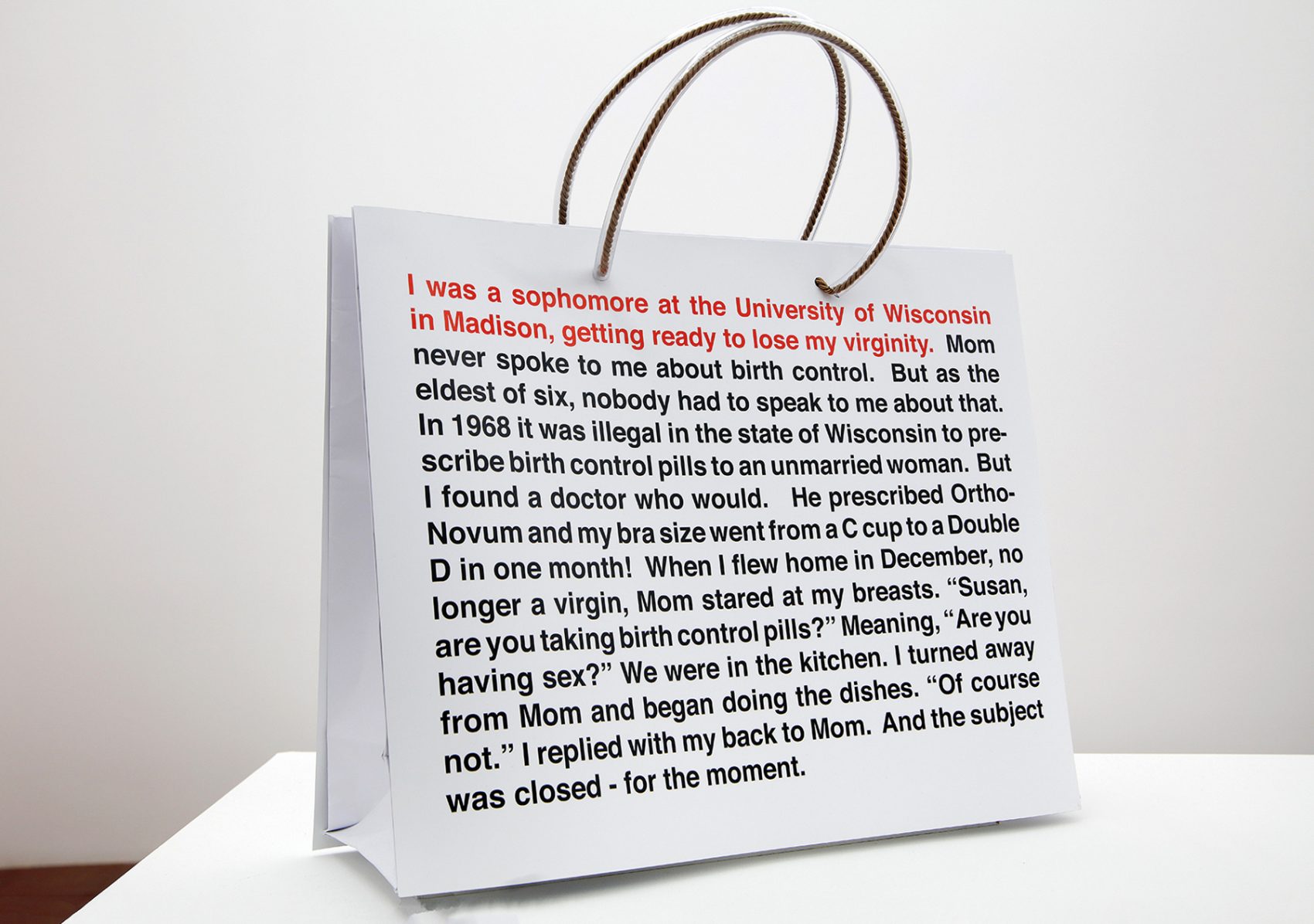

Shopping bags were centrally positioned on low pedestals. On every prototype, Mogul put a photo on one face and an autobiographical narrative paragraph associated with the image on the other. The text was rendered in black or red on a white background in the Helvetica typeface created by Swiss designer Max Miedinger in the late 1950s to evoke a Western postwar modernism that was rational and forward-looking. The cool, graphic look of Mogul’s bags, however, belied the sometimes audaciously confessional stories detailed in the texts. In one, an unmarried Mogul sought illicit birth control as a university student in Wisconsin and then fibbed about it while at home during a holiday break, after asked by her mother if she had become sexually active. The associated image was of an aged Ortho-Novum Dialpak dispenser.

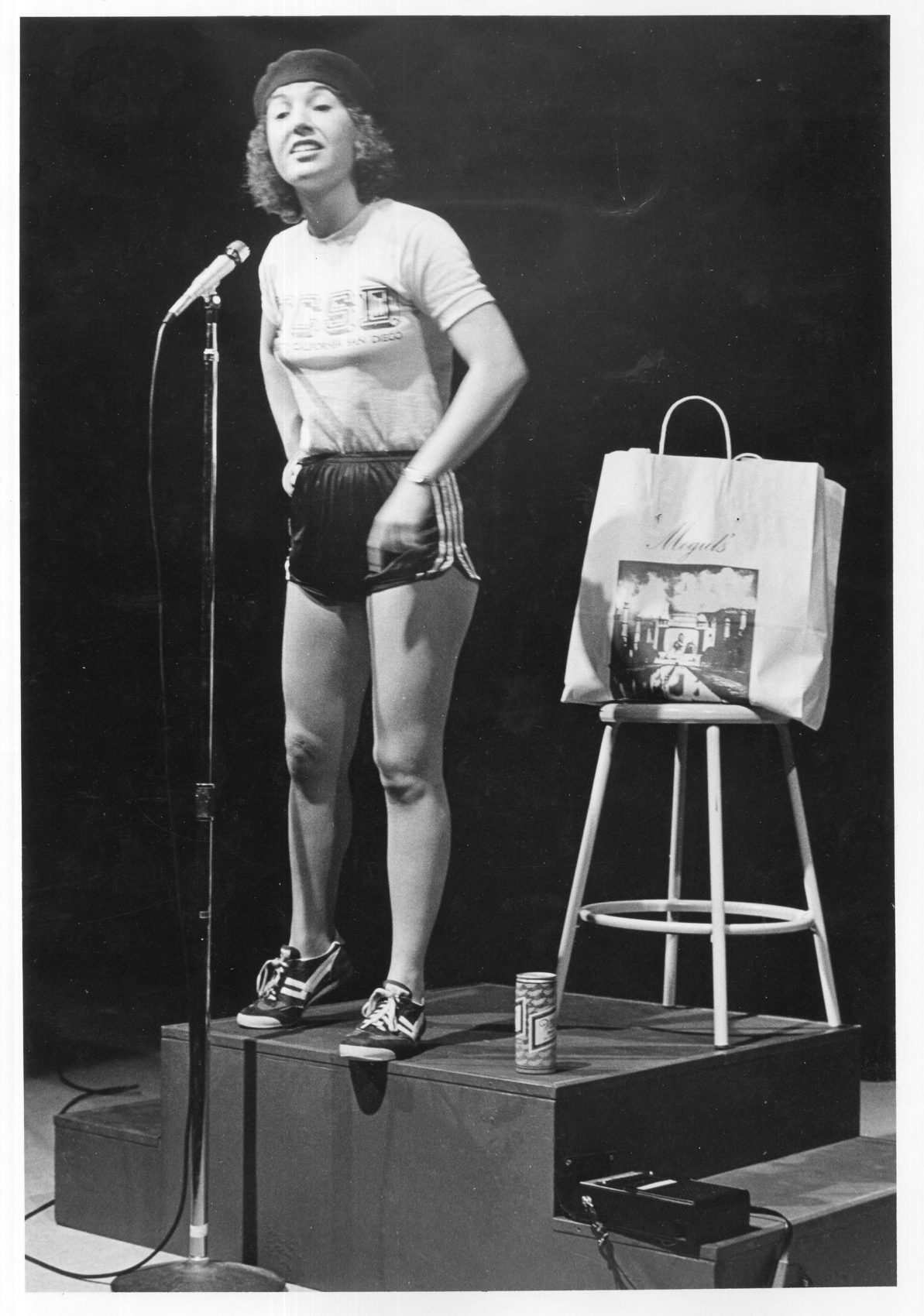

A cursory pass around Mogul’s show brings to mind Barbara Kruger’s most iconic aphorism, “I shop, therefore I am,” which was so readily consumable that it has been printed on everything from postcards to coffee mugs to T-shirts. Both Mogul and Kruger are second-wave feminists who came of age in the early 1970s and who appropriated the language and tropes of mass media and middle-class consumerism into their art. Paper shopping bags made their first appearance in Mogul’s 1976 solo exhibition Mogul’s August Clearance at Canis Gallery at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles.1 In that show, posited as a quiet rebellion against the “elite art world,” Mogul became a “shopkeeper” who displayed her photographs and photo collages on hangers and in bins.2 Purchases were placed in Mogul-branded bags she designed as a takeoff on the merchandising for a revered Brooklyn-based discount department store, Loehmann’s.3 For the bag’s image, she used a photo collage from the series Hollywood Moguls (1976–79), a punning play on her last name with which she explored imaginary personae as a female magnate conquering Tinseltown. Leaving nothing to waste, she would recycle the Moguls bags for standup performances like Live in San Diego (1977), staged at UC San Diego. This almost sedimentary layering of narrative through her repurposing of shopping bags reveals a core tendency that remains consistent today: less is never more. Mogul’s work often presents a surfeit of meaning—content inside content, personal asides and jokes—that challenges tidy categorization.

Susan Mogul, Live in San Diego, 1977. Publicity still from performance. © Susan Mogul. Courtesy of the artist.

If I were writing about Mogul in the 1990s, this superabundance might inspire me to digress into a narrative of hysteria, of resistance, of women “performing” their bodies and identities, and thereby elide any overtly feminist read of the exhibition altogether. By the 1990s, feminism was suspended in an awkward stasis. It was both out of vogue and fragmented by internal dissent. Momentum for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment had long since petered out, although women were beginning to experience the fruits of victories like Title IX. The earnestness of the second wave did not play well when postmodern irony was winning out over sentiment in the arts. Meanwhile, powerful postfeminist rhetoric chipped away at dated feminist motifs on the popular culture front. Then coming into my own as a writer, it felt safer to encode feminist ideas in a variety of theoretical conceits such as those related to the Other, abjection, and the simulacra, ideas made available in academic journals like October. Now, another wave of feminism (the fourth by most counts) is urgently pushing towards the shore. As happened before, this generation proposes to critique the movement and methods of the predecessor it surpasses. Amidst an undeniable upswell of gender activism in culture at large, it feels appropriate to reconsider Mogul’s practice in a historic register.

In one work on view at as-is.la, Free Associations (2019), Mogul aligned seventy-two five by seven-inch digital prints on the gallery wall in two columns of thirty-six, loosely organized by themes. Some images were grouped by colors, patterns, and shapes. Others depicted themes that were relatively innocuous, such familial scenes of a teenage Mogul and siblings chatting on the phone or lounging in the living room, in snapshots taken by their mother. Still others were freighted with heavier subject matter such as motherhood, fecundity and sexuality, and prior markers of female independence embodied in the labor of women like Mogul’s aunt Lea, who was a milliner by trade. Among the images were stills from Mogul’s videos and performances, thereby situating this serial artwork in the register of a retrospective. In one sequence, Mogul made plain the relationship of her playful 1974 video about masturbation, Take Off, to Vito Acconci’s somber and perverse Undertone (1973), a video she studied at the Feminist Studio Workshop while researching an essay “comparing male artists’ representations of their sexuality with female artists’.”4 Leaving nothing to chance, Mogul provided a printed key to her associations for gallery visitors to peruse. Beneath thumbnails of objects or images were succinct descriptions of what they signify to her. By acting as her own curator with Free Associations, Mogul brings to mind artists who used similar strategies to engineer the historicization of their practice. A classic example is Marcel Duchamp, who, during the tumult of the Second World War, assumed the persona of an itinerant cheese salesman across Europe, carrying sample kits, the Boîte-en-valise (1935–41), laden with miniatures of his distinctive proto-conceptual delicacies.5

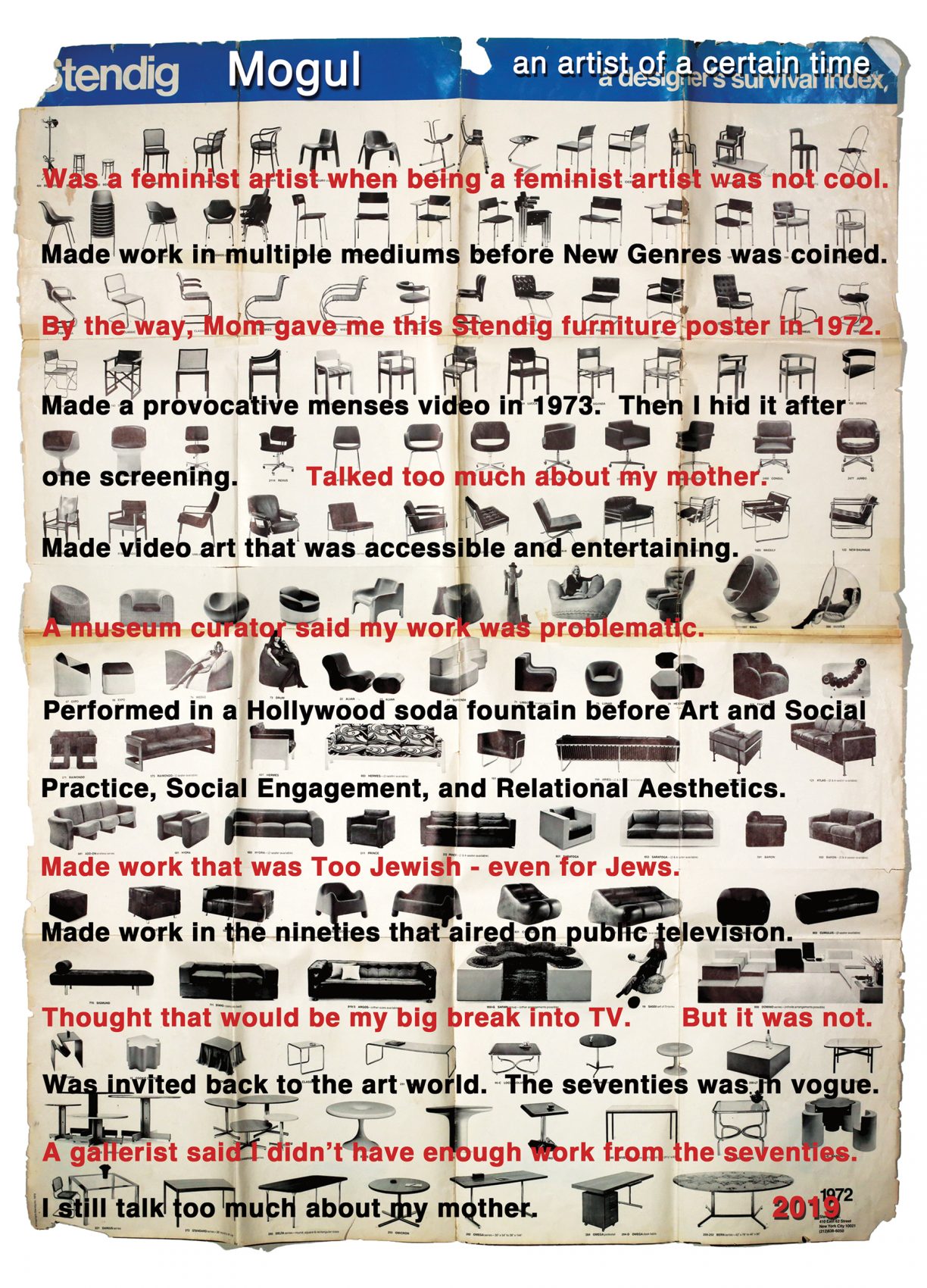

Another work at as-is.la, Artist of a Certain Time (2019), similarly brims with self-narrative content. Mogul photographically reproduced a tattered promotional poster, A Designer’s Survival Index (1972), which she identifies as a point of departure for the entire exhibition. Gifted to her by her mother, the poster catalogs essential pieces of iconic European furniture imported to the United States by Charles Stendig to satisfy America’s postwar craving for cutting-edge modernist home furnishings. Superimposed on the image of this fragile, ephemeral object is a digitally rendered, autobiographical layer of text in red and black. In this poster of a poster, Mogul blends two aspects of survival: beneath, the material things she and we gird ourselves within our homes to signify success; above, a blunt reckoning of her career and resilience as a female artist.

Susan Mogul, Artist of a Certain Time, 2019. Digital print, 36 × 50 in. © Susan Mogul. Courtesy of the artist and as-is.la.

With Artist of a Certain Time, Mogul also alludes to the recuperative tendencies inherent to events like The Getty’s 2011 initiative, Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980. To many local artists, this venture seemed to be one, at its crassest level, in which museums, curators, and commercial galleries approached the past like they were rummaging for deals at an estate sale. To be clear, Mogul was well-represented, with works featured in two major Pacific Standard Time (PST) surveys, Under the Big Black Sun: California Art 1974– 1981 at The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, and State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 at the Orange County Museum of Art. She was also commissioned by Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, to produce the documentary Susan Mogul’s Woman’s Building (2010) for the Pacific Standard Time exhibition at Otis’s Ben Maltz Gallery, Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building.

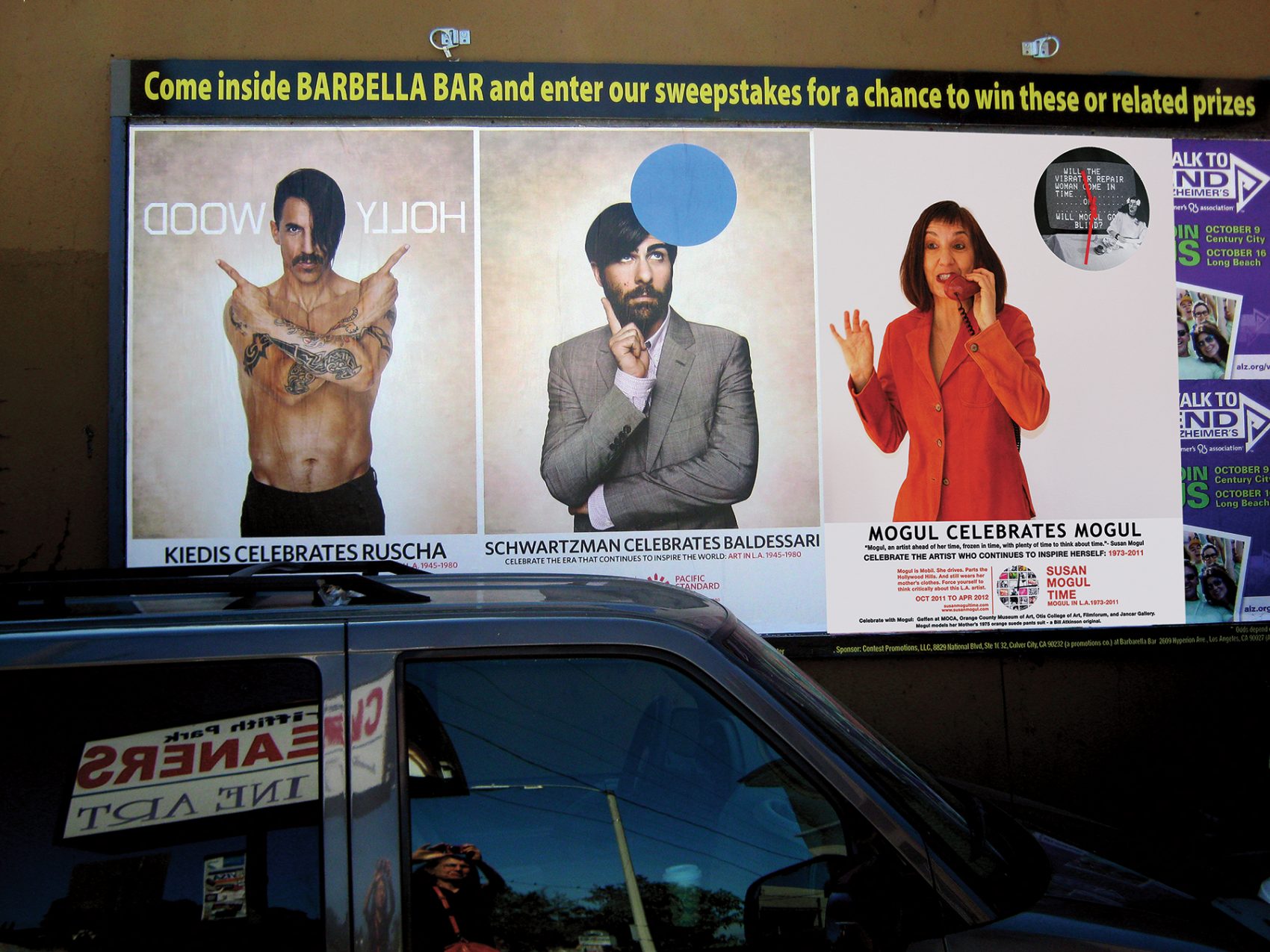

Even so, the taste-making determinations that sustain ventures like PST apparently struck a nerve for her. In 2011, Mogul produced a satirical publicity poster that she plastered guerilla-style in various neighborhoods in Los Angeles, titled Mogul Celebrates Mogul (2011). This work lampooned the advertising campaign for The Getty, which was displayed on billboards and in bus kiosks across the southland and that featured portraits of Red Hot Chili Peppers front man Anthony Kiedis and actor Jason Schwartzman in a swoon over artworks by Ed Ruscha and John Baldessari. In Mogul’s poster, she wears her mother’s orange suede pantsuit and identifies herself as “Mogul, an artist ahead of her time, frozen in time, with plenty of time to think about time.” Naturally, this same chic, 1970s-era Bill Atkinson pantsuit was on display at as-is.la, while Mogul’s portrait from Mogul Celebrates Mogul was tucked into the right grid of Free Associations.

Mogul’s recognition in The Getty’s first PST was no outlier. Her place in the Los Angeles art canon has been consolidated by inclusion in iconic Los Angeles exhibitions such as Sunshine & Noir: Art in L.A., 1960–1997, which originated in 1997 at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebaek, Denmark, and made its way in revised form to the UCLA Hammer Museum in 1998; the 2006 survey Los Angeles, 1955–1985: The Birth of an Art Capital at the Centre Pompidou in Paris; and the comprehensive 2008 survey California Video, co-organized by the Getty Research Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Susan Mogul’s Mogul Celebrates Mogul (2011) poster placed alongside the official Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980 advertisements on Alvarado Street, Los Angeles. © Susan Mogul. Courtesy of the artist.

Mogul’s early bona fides as a feminist artist are equally impressive. In a 1974 photo-essay in Ms. magazine about the Woman’s Building, Mogul holds up a television monitor on which her performance Dressing Up (1973) is playing, while stills from the same video can be seen on the wall behind her. In this video, Mogul performs a reverse striptease while reciting a comical monologue about shopping with her mother. Lucy Lippard enthusiastically called out Dressing Up in her 1976 anthology, From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art. That same year, writing for Artweek, Martha Rosler reviewed Mogul’s August Clearance. In 1977, Mogul’s photo collages were presented in a three-page spread in Chrysalis: A Magazine of Women’s Culture, an influential Los Angeles-based feminist publication.6 And in 1983, her mentor Arlene Raven included her in the notable feminist survey At Home at the Long Beach Museum of Art with artists such as Judy Chicago, Eleanor Antin, Suzanne Lacy, Rachel Rosenthal, Miriam Schapiro, and Faith Wilding, among others.

And yet, despite early critical success, Mogul’s place in feminist art history—as framed by third-wave writers and curators—has not been cinched, which makes her critique of historicization within works like Artist of a Certain Time and Mogul Celebrates Mogul all the more pointed. She was excluded from the 1996 survey Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s ‘Dinner Party’ in Feminist Art History at the Hammer Museum, even though she came to California in 1973 to study in the Feminist Art Program at CalArts and followed Chicago, Raven, and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville to the Woman’s Building. She made many works while there and in subsequent decades that correlated with the Hammer exhibition’s premise, an exploration of “female sexuality, ideals of beauty, domesticity, violence against women, the questioning of male authority, and the diversity of female experience.”7 Nor did Mogul’s work appear a decade later in WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution, a third-wave mother ship of a traveling exhibition and publication, which originated at MOCA in 2007. Limited to the period between 1965 and 1980, WACK! codified the time frame when “feminist art” passed into the historic register. Although 120 artists from twenty-one countries were included in this sprawling, celebratory survey, there was much rumbling sotto voce about who did or did not make the cut. It’s no surprise that, after viewing the show, a friend asked Mogul whom she had alienated.8

Back when Mogul began her investigations of female identity, the catchphrase of second-wave feminists was “The Personal is the Political,” which arose from the context of group consciousness-raising (CR) meetings in the late 1960s.9 Speaking in 2012 with feminist artist and writer Rebecca La Marre, Mogul addressed the role of CR in her practice as a young woman working in the Woman’s Building: “We would all sit around and the first subject would always be our mother! I don’t remember why, but I suspect it was because we wanted to figure out female identity and how to be different from our mothers and have a different role.”10 Over the years, in photographic self-portraits, videos, and live performances, Mogul has continued to develop ideas first explored in those CR sessions. In particular, she has assumed various personae as a mechanism for investigating herself and the “social façade” of sexual identity.11 Because the lived experience of women was a legitimate topic for art making, Mogul and friends like Ilene Segalove raided the closets of their mothers for inspiration. In the mid-1980s, the elder Mogul gave the younger Mogul clothing that no longer fit her. Mogul responded by producing a series of performances called News from Home (1985–87) in which she played the roles of mother and daughter, modeled her mother’s hand-me-downs, and read aloud twenty years of their correspondence with one another. Rhoda Mogul reacted to her daughter’s artistic appropriation by adding a copyright symbol to salutations in subsequent personal letters.12 Although referenced in Less is Never More, Mogul explores News from Home more fully in Mom’s Move, a project through which she acknowledges the significant influence her mother had on her development as an artist and filmmaker. While the footage in Mom’s Move is filled with funny banter between the two, it is obvious by the edge on some of her words that Rhoda Mogul was ambivalent about being “subjected” to, and by, her daughter’s creative scrutiny.13

Susan Mogul, Free Associations, 2019. Seventy-two digital prints, each 5 × 7 in. © Susan Mogul. Courtesy of the artist and as-is.la. Photo: Julie Shafer.

In 1970s-era feminist manifestoes like Hélène Cixous’s “The Laugh of the Medusa” (1976), humor was identified as a mechanism to defy and disrupt the patriarchy.14 Having already discovered that video could be a “leveling” medium for female artists, Mogul realized, too, with the success of early video projects, that people found her funny.15 While this led to opportunities for performances and screenings, her reliance on wit sometimes had unintended consequences. Reviewing a 1976 presentation of four videos at the Anthology Film Archives in New York—Dressing Up (1973), Take Off (1974), Mogul is Mobile Part III (1975), and Big Tip/Back Up/Shut Out (1976)—Artforum critic Leo Rubinfien described Mogul’s raucous monologues as a “flexible mixture of Yiddish comedy, feminist sincerity and pseudo-conceptual art self-consciousness.”16 Rubinfien goes on to say that “Mogul’s ethnicity at times becomes overbearing,” a sentiment that she may in fact point to in the text of Artist of a Certain Time when she describes how she “Made work that was Too Jewish – even for Jews.” Could it be that Mogul’s fealty to a style of personal exploration informed by second-wave consciousness-raising diminished her appeal to third-wave feminist curators and art historians in the 1990s and 2000s when such modes of expression were out of fashion? Was her humor too broad or too ethnic? Or was it because, at a certain point in the 1980s, she stopped identifying as a feminist artist because she felt confined by a definition that had become “very small” and necessitated the production of work that was strictly political?17

Even in its heyday, fissures in the feminist art movement could be observed from outside. Acting as a sympathetic ally in the mainstream art press in 1976, critic Lawrence Alloway wrote enthusiastically about the prospects for feminist art to become truly avant-garde in ways other movements of the twentieth century had failed. In his analysis, this art had the potential to induce change “beyond the revision of formal matters,” because of access to a large public audience that was better informed through improved education and therefore had increased expectations.18 What contributed to the innovation of women’s art, he felt, was its “non-stylistic homogeneity,” a factor that “makes some women abstract artists feel closer to women representational artists than to male abstract artists.”19 At the same time, he cautioned against a tendency of exclusiveness he had already observed from articulate advocates like Lippard, Chicago, and Schapiro, who espoused a general theory of essential “female imagery,” without considering artwork that fell outside its scope. Alloway pleaded for a more elastic concept that could include artists like Nancy Spero, among many others named, observing that it would be “both more rational methodologically and more in keeping with the movement’s desire for diversity/equality if critics were to avoid exclusionist tactics.”20

Susan Mogul, Birth Control, 2019. Digital prints, paper shopping bag, braided cord, and plastic tube, 16 × 20 × 6 in. © Susan Mogul. Courtesy of the artist and as-is.la. Photo: Julie Shafer.

When third-wave feminism arrived, informed as it was by poststructuralist, postmodern, queer, postcolonial, and intersectional frameworks, it provided a much-overdue course correction. However, somewhat lost in the transition was the non-stylistic homogeneity that Alloway found so promising. With the rise of Women’s Studies programs at the university level, some believe academia hijacked third-wave feminism and made it more theoretical.21 While scholarly journals on the topic proliferated in the university setting, the public flow of contemporary feminist thought was ebbing. Even popular mainstream publications like Ms. struggled to remain solvent. Meanwhile, influential early third-wave feminists pejoratively dismissed consciousness-raising as “victim feminism,” which resulted in whole swaths of women’s art practice being branded as passé.22 By then, Mogul had jumped the tracks, transitioning from art making to independent filmmaking, which placed her on a professional path of mainstream public television and the film festival circuit that ran parallel to the art scene. In the most generous reading of her situation within feminist art, during the redemptive 1990s and 2000s, Mogul was perceived by the gatekeepers as a colorful character in a chapter that had already closed and thus could be left behind.

Whatever the case, her DIY boutique retrospective at as-is.la made clear that Susan Mogul has learned the hard lessons of the 1970s and beyond. She will no longer wait for someone to grant her validation as a woman or artist. She will take it for herself. And whatever debates may have ensued between mother and daughter appear to be gently handled in Mom’s Move. At one point, Rhoda Mogul describes why she took up photography, saying, “I don’t like things that women did. I like the things that men do.” In the next sequence, Mogul asks whether her feminism had influenced her mother’s decision in the mid-1970s to take nude self-portraits in the shower, and her mother candidly responds, “No, I don’t think so.” Mogul does not argue, leaving it at that. Exposing a generational divide that cleaves their aspirations as artists, this exchange is also a reminder that feminine praxis has always been legion (and will likely remain so). At the Echo Park screening, a surprising number of Susan Mogul’s students from the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts clustered affectionately around her like she was a beloved grandmother, a circumstance that must sometimes make this feminist artist, who is childless by choice, laugh out loud.

Rhoda Blate Mogul passed away on April 16, 2020, in Port Washington, Long Island, New York. She was 95 years of age. Due to the pandemic, Susan Mogul was unable to attend the burial service on April 20. On that day, Mogul wrote the following in tribute to her mother.

Although my mother called herself “Rhoda Right,” Mom was always on my side. Not in terms of an argument with her. Oh, no. But Mom believed in me. She believed in me as an individual, and as an artist. And Mom never had a cookie-cutter idea of how I should live my life. Never once did she ask, “When are you going to get married?” Or, “Don’t you want to have children?” Never.

And Mom showed up. She always showed up. Sure, she was embarrassed when she drove from Long Island to a lower Manhattan underground arts venue, only to be faced with her daughter naked on screen. No matter. She showed up. And Mom continued to show up. Whether it was in a marginal neighborhood in New York City in the eighties or a museum in Los Angeles, Mom showed up. She always showed up.

Before Mom sold her home and moved, I went through her entire photographic archive. I examined her proof sheets, negatives, and photographs. I saw photographs I had never seen and images on proof sheets Mom had never enlarged. These “new” photographs from the fifties and sixties enabled me to examine and ponder my childhood, my relationship to my mother, and the home I grew up in from a somewhat different vantage point.

When I visited Mom at her apartment at the Amsterdam, the independent living facility she moved to, I showed her black-and-white photographs from her archive and I projected hundreds of slides on her carousel slide projector. It was a great way for us to connect, particularly because Mom’s dementia was not conducive to a free-flowing conversation. But when it came to her photographs, Mom perked up and always had an interesting comment. Mom may have had dementia, but her visual acuity was perfectly intact. Over the course of the last few years, Mom repeatedly said, “You are my curator.” And that was all I needed to hear. I was unable to be the caretaker of my mother in the last years of her life. But I did become the caretaker of her work.

–Susan Mogul

Mom’s Move by Susan Mogul. Limited Screening available on X-TRA’s site through September 30.