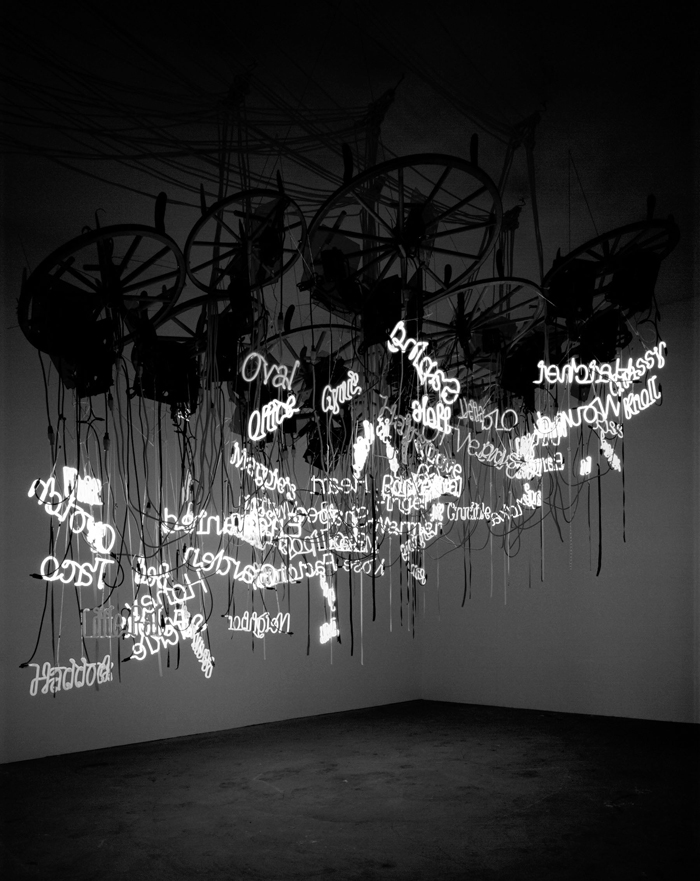

Jason Rhoades, Twelve-Wheel Waggon Wheel Chandelier, 2004. Glass, wire, neon, wood, plexiglas, lace, and plastic; Dimensions variable. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, and David Zwirner, New York.

Like many newcomers to the city, Hammer Museum curator Gary Garrels wanted a specific “Los Angeles” experience. So, a mere 18 months after arriving, he was finishing the catalogue for his exhibition about Los Angeles art in an effort, one presumes, to map out the terrain and come to grips in some small way with this sprawling, de-centered metropolis and its sprawling de-centered art scene. Understandably then, Eden’s Edge assumes an autobiographical stance, since it is a document of Garrels’ exploration and introduction to the city’s artistic climate. His enthusiasm and his hesitancy are equally apparent in the organization of the show, but, unfortunately, the result is an exhibition that does not speak coherently about the current state of art production in Los Angeles. Not that such an exhibition, with only fifteen artists, could or should aspire for comprehensiveness—far from it. However, the show begs for at least one pendant exhibition, fleshing out significant omissions.

Most obviously, since the birth in the mid-1950s of the scene we know today, Los Angeles artists have, very broadly speaking, followed two distinct approaches to materiality. This exhibition, with its predominantly boisterous, colorful, bric-a-brac aesthetic, seems to argue that one of those approaches, namely assemblage, remains dominant and persistently influential. Although the obvious precedent for the vast majority of the work in the show, this claim is never made explicit—nor are any of the founding practitioners like Ed Kienholz identified by name. In any case, even the most convincing version of this argument would need to address at some level the abundance of artists associated with the other significant artistic movement—assemblage’s quiet cousin, West Coast Minimalism. Not so much as a cursory mention is made of Minimalism, its founders, or those who continue the tradition today. By omission, it is implied that Los Angeles art is without a substantial, intellectually driven history

All of that said, much of the work included in Eden’s Edge is superb and speaks volumes for itself, which allows for easy distraction from Garrels’ missing argument. Rather than mixing it up, the works are presented as if each artist has his or her own project room. As a consequence, compelling “conversations” between pieces in adjacent galleries are best described as “overheard” (such as those between Elliott Hundley and neighbor Mark Bradford, for example). All of this facilitates the viewer’s movement through—and pauses in—the gallery spaces. The strongest work in the exhibition (that of Bradford, Ken Price, Monica Majoli, Ginny Bishton, Liz Craft, Matthew Monahan, and Jason Rhoades) nevertheless seems self-contained and benefits from the exhibition’s generous layout.

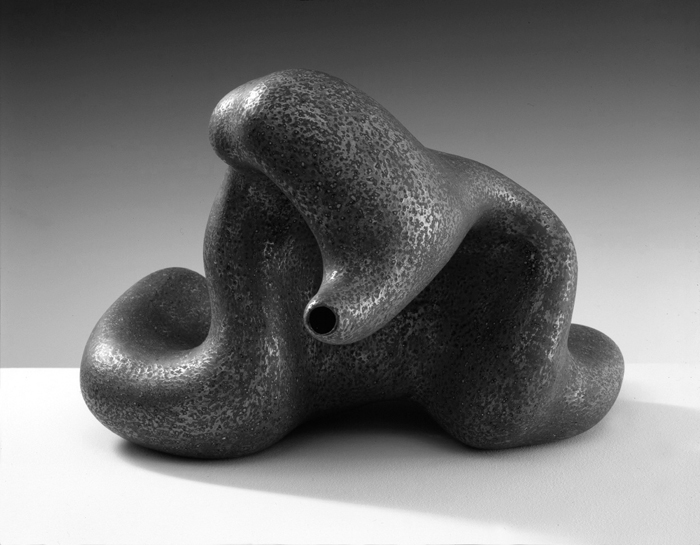

Ken Price, Zigzag, 1999. Acrylic on fired ceramic, 11 1/2 x 17 x 19 1/2 inches. Collection of Don and Joan Beall. Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, California. Photo: Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, California.

Quite sensibly, Garrels does not aspire, in the limited space of this exhibition, to come to grips with the complex range and texture of art made in LA. Practical or not, however, this humility unfortunately leads to repeated hedging. For instance he notes: “…I have become interested in art here that grapples with the complications and ambiguities, that recognizes the undertows but also the exuberance, of life in the city—which is not dissimilar to the condition of the country as a whole.”1 It is not that Garrels’ observation is incorrect but this “local-as-global, global-aslocal” trope does not satisfy as the premise of an exhibition. With any place, there is some local specificity, and in many ways Garrels has found Los Angeles’, or at least the version he wanted to find and one that does indeed exist. But he is also abundantly cognizant that geographical distinctions are more and more blurred with the help of global economies and the marketing of culture and thus, he seems to say (although not explicitly enough), the charge of surveying an aspect of culture from any one major metropolitan area is fraught with insurmountable obstacles and contradictions. In deference to a very legitimate difficulty, Garrels appears to have simply lumped together fifteen project shows by artists based in Los Angeles and branded it a survey of current production in this region. This would be a more honest premise and one that would make the show far more palatable since it would declare its own incoherence from the outset.

Giving the title Eden’s Edge to an exhibition about recent art in Los Angeles invites comparison to Paul Schimmel’s watershed exhibition Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Temporary Contemporary (now the Geffen Contemporary). This darker and bleaker assessment of Los Angeles was tightly curated and has had a lasting impact on the city’s artistic community (and outside conceptions of it). After all, two of the fifteen artists in Eden’s Edge were also in Helter Skelter: Lari Pittman and Jim Shaw were included as part of the current exhibition’s “foundation”2 that “establishes a generational continuum” with newly emerging artists.3 The impact of Schimmel’s show, which opened on January 26, 1992, is not simply the result of its gutsy title and even gutsier focus on art from the 1990s. Rather, Schimmel clearly states in the closing line of his catalogue essay that the exhibition was “one vision of L.A. art in the 1990s.”4 His curatorial vision was described by Peter Schjeldahl as “aim[ing] to hit the wrong note squarely,” an assessment acknowledged by Schimmel.5 Such a transparent, declarative approach might have benefited Garrels’ show.

So what about the primary characteristics of the work in Helter Skelter? Do they persist in Eden’s Edge? The anxiety, apocalyptic vision, and aggressive tendencies seem to have made way for more organic, colorful, and sometimes humorous visions, of both the dark and light-hearted varieties. Personal symbolism and artistic personality are as strongly visible here, with an overall feeling of greater buoyancy. This is not to say that the work is incapable of moodiness. A number of Matt Greene’s dreamscape paintings are more than mysterious—they are downright sinister in their depictions of sex-riddled diablerie. One such work, By the Lust of the Basidiomycetes Shall Every Perversion Be Justified (2004) is populated by nude women and mushrooms set against fuliginous backgrounds and blasted areas of white. Another work, For the Eyes of Our Fathers (2005), in particular, brought to mind Llyn Foulkes’s Pop (1990), a traumatized (or traumatizing) paternal figure with bulging eyes set off by ominous lighting.

Ginny Bishton, Walking (Yellow), 2003. Photographic collage, 15 x 13 1/2 inches. Private collection. Photo: Courtesy of Richard Telles Fine Art.

While much of the strongest work in the show can be described using the language above (organic, colorful, etc.), some pieces retain a latent insidiousness that suggests a connection to Schimmel’s vision. Rebecca Morales’s gouaches and watercolors on vellum are exquisite in their fuzzy, jewel-like depictions of plants and flowers. But the jagged, curling edges of the vellum remind one that it is in fact calfskin; even more unsettling is the unnatural-looking, cancer-like growth of her botanic subjects, particularly when coupled with synthetic hair. Ginny Bishton’s shell-like collages made out of thousands of photographic fragments likewise seem on the verge of further organic growth and movement. Indeed, the photographs were taken by Bishton on daily walks. Their beauty can be ascribed in part to their miniature quality—tiny specks of color that required painstaking labor to arrange.

The psychological component of Bishton’s collages, as characterized by the draw and/or repulsion to obsessive-compulsive tendencies, provides further fascination and hints at lurking danger. This “accumulation aesthetic” is to be found almost throughout the exhibition, for instance in the paintings of Lari Pittman and the assemblage works of Elliott Hundley and Jason Rhoades. Mark Bradford’s collaged paintings read topographically and as personal memoirs, somewhat akin to Bishton’s work. Bradford’s work is more looming, grand even, yet it is marked by the same concinnity.

The “more expressionistic, personal aesthetic” of art in California that Garrel’s identifies, in contrast to the “cool intellectualism of art in New York,”6 is certainly in evidence in LA but is not any more pronounced here than anywhere else—pick up any recent issue of Artforum or visit an art fair to prove this point. New York is no longer the city of the late 1960s. Garrels points out the rich heritage of assemblage in Los Angeles—an active heritage that is now diffuse—with silent yet hearty nods to such figures as Kienholz, Wallace Berman, and subsequent locally influential practitioners such as Bay Area artist Bruce Conner. But what are we to make of the legacies of the Finish Fetish and Light and Space artists? What of Irwin and Turrell? Bell and Alexander? Kauffman and McCracken? Has this sleek manner evaporated into thin air as this exhibition argues tacitly? Again, these omissions suggest a pendant show.7 Assemblage has had its time in the sun; perhaps the time is right for another tradition to take center stage?

Anna Sew Hoy, Dark Cloud Version II, 2006. Glazed ceramic, rope, suede lace, glass, and mirror; 22 x 21 x 18 inches. Collection of schiff art projects & management llc, New York. Courtesy of Karyn Lovegrove Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Courtesy of Karyn Lovegrove Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo by Robert Wedemeyer.

One thing is certain: Eden’s Edge demonstrates what Thing: New Sculpture from Los Angeles, previously exhibited at the Hammer, explicitly set out to prove, that the peculiar strength of Los Angeles lies in sculpture. Ken Price’s ceramic sculptures, with their heat map-like surfaces and organic forms, are like sexy, un-stately updates of Henry Moore sculptures. And the stand-out works from the exhibition are arguably Matthew Monahan’s mixed-media sculptures featuring innovative use of materials and classical figuration. The Seller and the Sold (2006) is profoundly moving, with its tomb-like vitrine, muted palette tinged with gold, and strangely postured, fragmentary figures rendered uncannily in opposing scales.

Although Garrels always intended on having a Jason Rhoades installation in the vaulted gallery serve as the finale of the exhibition, it seems particularly fitting given the premature death last year of such a prodigious talent.8 The Twelve-Wheel Waggon Wheel Chandelier (2003) surprisingly looks as if it was made for the gallery (or vice-versa), although the space was built originally to house the Leonardo Codex. What is remarkable about the installation is that a pornographic, neon sculpture hanging from the ceiling manages to look dignified and spiritual, dirty yet clean as a whistle, rugged yet refined, utterly preposterous yet disarmingly elegant.

Rebecca Morales, Tamara’s Cues, 2004. Gouache, watercolor, and ink on calfskin vellum; 34 x 24 inches. Collection of John Lee/Karin Bravin.

The curiosity (intellectual or otherwise) behind one’s enthusiasm to understand a place is usually earnest, often revealing, and always admirable. Los Angeles has been given more than its fair share of such attention, and the city and its artists can only benefit. The work in this exhibition is uneven at times, teetering between extremes, but the “journey” Gary Garrels intends for the viewer, “in which subjects and themes, materials and formal treatments…reverberate, ricochet, and overlay each other,”9 is an effectively plotted one, and the decision to give discreet space to each artist benefits the collective experience. Contemporary culture might easily be described as globally and locally heterogeneous with pockets of homogeneity. Eden’s Edge is such a pocket. Los Angeles brims with talent but it doesn’t seem edgy and angry in a way that it once did. Nor does it seem Edenic either. It does seem hopeful, perhaps more than some places, and this might come from self-awareness of its relative youth and its path of self-becoming. Eden’s Edge is an entertaining glimmer on this arc, but it seems unsure of its own identity. Is it an argument? Surely not. Is it an account of a migrating curator’s attempt to calibrate this experience? Probably, but is this really the basis for a major show? Moreover, does it add anything to our understanding of the concerns that structure art production in Los Angeles? Norman Klein, in his catalogue essay for the Helter Skelter exhibition, quoted critic Louis Adamic as writing, in 1929: “Los Angeles is America. A jungle…It is still growing. Here everything has a chance to thrive—for a while…”10

Jennifer Wulfsson is senior editor of the Bibliography of the History of Art at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.