Paul Ramirez Jonas, Talisman, 2008. Image courtesy the artist. 2500 keys to the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, exchange booth, 2500 visitor keys. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Roger Björkholmen Galleri, Stockholm.

Over the past century, mega-exhibitions have differentiated themselves from conventional gallery and museum showings through dizzying displays of plenty in multiple venues showcasing myriad works by expected and emerging international talents, and resembling all-you-can-eat buffets more than conventional “white cubes.” Yet, overabundance comes at an untold cost, as the striking absence of works in the 2008 Sao Paulo Bienal symbolizes. The now-famous nothingness posited as a crucial component of the most recent Bienal, curated by Ivo Mesquita and Ana Paula Cohen, was likely precipitated by the art world’s living far beyond its means–not to mention a persistent one-upmanship that often prioritizes splendor over substance. Interestingly, the 2006 iteration of the Sao Paulo Bienal eerily foreshadowed this current crisis of (non) representation.

When visitors to the 2006 Bienal entered the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, they were immediately confronted by Jane Alexander’s site-specific installation, Security with the Harvest–which showcased an emaciated, biomorphic sculpture awkwardly surrounded by a grassy plot, mounds of working gloves, rusted sickles, chain-link fencing, and barbed wire. Monitored constantly by a looming contingent of armed security guards who were part of Alexander’s piece, the work’s sociocultural references resonated bluntly with the year’s headlines–the ill-treatment and sequestration of foreigners regularly documented in reports about united States military operations at Guantanamo Bayand Abu Ghraib. At the same time, Alexander’s work alluded to long-simmering incommensurabilities in the contemporary art world–between local experiences, increasingly global(izing) exhibition methods, and homogenizing, utopian themes that perpetuate the illusion that disparate artistic practices and mega-exhibitions are comfortable bedfellows. Alexander’s installation metaphorically exposed the significant layers of separation between the artwork and the changes ultimately wrought on it by its method of display, between artificial (and idealized) settings and the brutal realities that surround and undermine them. Indeed, these tensions collectively underpinned larger predicaments posed by the 2006 Bienal’s curator Lisette Lagnado, which lingered as preparations for the 2008 Bienal commenced: “How to break a museum, a gallery or even a biennial visitor’s expectation by showing something that would not be a ‘work of art,'” whilst acknowledging that the “museum cannot remain empty.”1 Lagnado’s contemplation of a rupture between the realities documented by art and the expectations that umbrella it certainly called into question the effectiveness of the mega-exhibition as an institutional arbiter of art, history, and experience. Yet, it also revealed a “biennale crisis” of sorts, born of an inability to identify just what specific function mega-exhibitions should have these days, what relationship they should establish with domineering and underrepresented histories, and what institutional credibility they can maintain when they are dismissed by some critics as economically indulgent “cultural safari[s].”2

The 2008 Sao Paulo Bienal’s relative barrenness may appear to be consistent with the conceptual challenges to the autonomy of the “white cube” and its associated mechanisms of institutionalization as explored in the initiatives of Mel Bochner, Yves Klein, John Cage, and Ana Mendieta, to name just a few. Yet, these artists’ doubts regarding the sanctity of art objects and their gravitations to the primacy of idea, immateriality, and intervention were born of a self-motivated, avant-gardist evasion of tradition and academicism, not necessitated by a looming financial catastrophe within the art world. Facing the loss of longstanding contributors (who felt burned by the Bienal Foundation’s ongoing fiscal mismanagement), a budget cut of 40 percent handed down by Bienal Foundation President Manoel Francisco Pires da Costa, a reduction in participating artists from 120 to a meager 42, and a viewing public that grew increasingly hostile to the proposed exhibition, curators Ivo Mesquita and Ana Paula Cohen assumed the formidable tasks of convincingly situating the troubled 2008 iteration of the Bienal amongst its peers and preventing it from collapsing under the weight of its own history. Despite its initial success in bringing modern Western works of art to South America in the 1950s and later establishing itself as a vibrant, non-Western exhibition alternative to the Biennale di Venezia, the 2008 Sao Paulo Bienal had been effectively foreclosed in the two years leading up to its opening. Thus, in a cavalier, making- lemonade-out-of-lemons style, Cohen and Mesquita opened up the inner workings of the exhibition and its evolution to critical scrutiny. In the end, their curatorial agenda needed to legitimize what Pires da Costa euphemistically described as a “reflexive pause,”3 but also required a tenable conceptual framework that could contribute meaningfully to and further propel existing global mega-exhibition traditions and discourses.

In 2007, Mesquita’s initial plans outlined what one might call the “bienal-as-biohazard,” the gravely ill patient requiring what the curator described as “quarantine [and] suspending a process in order to allow for some self-examination.”4 However, in the exhibition’s catalogue, Mesquita and Cohen camouflaged the exhibition’s programmatic difficulties by more purposefully describing the scaled-back proceedings as “a platform for observation and reflection upon the culture and system of biennials within the international art circuit.”5 Astonishingly mute regarding its fiscal woes, the Sao Paulo Bienal missed a critical opportunity to link its own debacles to the now-pervasive, increasingly global rhetoric of financial ruin and overextended living.

Instead, the exhibition catalogue packaged absences and shortcomings as “experiment[s]” with “exhibition, debate, and dissemination apparatuses,”6 six of which served as the organizational pillars of the Bienal: square, video lounge, open plan, plan of readings, publications, and educational services. However, the exhibition never adequately addressed some of the more fundamental relationships between these compositional apparatuses: how (and why) they should function in a particular way given an increasingly global art market; how they should relate to one another and mediate the roles of and contacts between artist, artwork, institution, and viewer; and how they could serve as the connective tissue between the Bienal’s history, the city, and a panoply of contemporary circumstances.

The sweeping, glass-paneled enclosure on the ground floor of the pavilion designed by Oscar Niemeyer and curatorially re-badged by Mesquita as “the square,” was intended as a crucial prefatory nexus linking the academic interests of the Bienal with the more recreational nature of Ibirapuera Park in which the pavilion is situated. Curators fashioned the square (usually the location for some of the Bienal’s larger and more eccentric artworks) into a contemporary agora –inviting passersby to circulate throughout a reconfigured gallery space that would more consciously embrace everydayness and serve as the spatial “join” between high art and the outside world. Initially, Mesquita wished to remove altogether the numerous glass panels in this area to punctuate the interconnectedness of and flow between park and pavilion, but costs proved daunting. Instead, large doors were opened on either side of the square–a far more understated gesture that, coincidentally, facilitated the surveillance of entrances and egresses. Underscoring the Bienal’s yearning for “living contact,” a work by Honduran artist Paul Ramirez Jonas confronted and reworked the operational policies and procedures of the pavilion itself. In exchange for a copy of a personal house, office, or car key, a visitor could receive one of 2,500 copies of the very key to the front door of the Bienal. Yet, such tantalizing freedom was not absolute as new keyholders were contractually obligated to use the key only during specified hours outside the exhibition’s usual opening times, to remain within the ground floor square when they entered, and to occupy the space with little more than meditative intentions. Speculating on the ultimate consequences of a potentially overextended degree of trust, Jonas’s performance/installation both crystallized the importance of dialogue within the mega-exhibition and exposed the fallacies inherent in imagining the square as a truly democratized space. Unlike prior editions of the Sao Paulo Bienal in which curators encouraged artists to assume the mediatory roles of “border guards of a realm that lies beyond the administered world,”7 artists in the 2008 Bienal seem to be pushed back into the regulated world–their practices offering glimpses of resistance to spatial discipline, while sadly exposing their ultimate accountability to or domination by it. For all its emphases on radically rethinking the art world and the overarching culture of biennials, this exhibition kept artists and viewers on a very short leash. In a manner not unlike the 2008 Biennale of Sydney’s lip service to artistic “revolutions” that, in the end, were repeatedly thwarted by institutional interference and curatorial side-stepping, the Sao Paulo Bienal concomitantly invited viewers to reconsider spaces and contexts and reprimanded those participants who chose to do so.

Interestingly, keys to the building also served as metaphorical keys to the city. One of the lone installation works in the square, All’s Well (2008) by Brazilian artist Rubens Mano, reflected on the immensity and congestion of Sao Paulo by filming its urban sprawl from a helicopter–aerially traversing one side of Sao Paulo to the other at a constant speed–and projecting the view within a claustrophobic viewing booth reminiscent of a literal “white cube.” By diminishing obvious references to people and their interactions that might otherwise be experienced at street level, suspending the usual sign systems by which metropolises are navigated and known, and containing this re-scripted experience of urbanness within a clearly defined architecture in the Bienal’s square, Mano’s work mirrored the broader curatorial ambitions of Cohen and Mesquita. Offering a perspective that revealed new views of Sao Paulo’s countless buildings and infrastructures, Mano acknowledged that a habituation of perception requires reinvigoration–a revitalized way of seeing that can challenge the viewer’s understanding of the urban as readily as Mesquita’s act of curatorial suspension can challenge the procedural traditions and expectations of mega-exhibitions. Despite Mesquita’s noble desire to use the “square” to “create energy to air the building,”8 All’s Well fails in its incarnation in this exhibition. As opposed to Mano’s original configuration of the work, Suspended Contemplation (2008), in which viewers must cross a wobbly footbridge and look down through its cracks in order to see the artist’s video of the city, All’s Well removes the precariousness that could have mirrored the Bienal’s compromised condition. Instead, the architecture that contains and conceals Mano’s video reasserts the primacy of the white cube; its inexplicable, almost-camouflaged presence acts as a sentinel in the largely barren “square” and stymies the artist’s attempts to transcend the congestion of the city and the containment of representation.

Carsten Höller, Valerio Sisters, 2008. Stainless Steel, Polycarbonate, Galvanized Steel, Length: 1,402 cm. Diameter: 80cm. Image courtesy: The Artist, Gagosian Gallery, London and Esther Schipper, Berlin, Photo by Amilcar Packer

Given the show’s constant insistence on rethinking spaces, artworks, and institutional paradigms, one might be surprised that a large-scale exhibition rumored to be so bereft of “content” was protected scrupulously. Guards performed obsessive pat downs, metal detectors were set to incredible levels of sensitivity, and wandering observers admonished viewers not to touch, not to run, not to rearrange haphazardly placed foam seating blocks. In short, viewers were urged not to behave in any way other than one would within a conventional gallery or museum setting. For a biennial that Mesquita and Cohen characterized as a liberated and liberating “place of potential,” visitors had very little latitude to question or to subvert the normative elements of traditional exhibition. Unfortunately, such time-consuming gatekeeping served as the conceptual foundation of viewers’ passage into the body of the scaled-back show. Thankfully, Carsten Hoeller’s Valerio Sisters (2008)–a steel and polycarbonate slide installation puncturing the exterior of the pavilion and twisting its way from the second and third floors to re-enter the square below–transported visitors in a swift, seven-second journey that contrasted with the entrance’s tedious, airport-like security detail. Hoeller’s work was also a compelling antithesis to the pavilion’s usual insistence on movements regulated by escalators, ramps, or elevators–original features of the modernist structure that would require average viewers at least ten minutes to negotiate moving from the top to the bottom floors. ultimately, the piece punctuated important contrasts between Modernism’s frequent reliance on order, logic, and symmetry and contemporary art’s occasional playfulness, in which sheer functionality and enjoyment have the potential to overlap.

On the first floor, Maarten Bertheux, Carlos Farinha, Isabel Garcia, Clarice Reichstul, and Wagner Morales curated one of the Bienal’s most intriguing components, the “Video lounge.” Placed in orbit around four thematic strands–telepresence, everyday (real life), music in action, and performance the changing sequence of videos was intended to showcase both a “confluence of questions” posed by all contemporary video artists, and a sense of post-1960s interdisciplinarity in which the formal elements of film, television, theater, computer technology, and visual art are increasingly shared and conceptually re-fashioned.9 Some memorable works on display, such as Love-In Festival (1968) by the dots-obsessed Yayoi Kusama, not only underscored the often-fluid boundaries between propriety and titillation, performativity and privacy, inhibition and impulsiveness, but also clarified how Kusama’s circular and spherical compulsions can generate such different meanings and interpretations. With its conglomeration of B-grade porno music tracks, kaleidoscopic lighting effects, and writhing bodies, Love-In Festival certainly resonated with the Bienal’s larger ambitions to consider the biennial phenomenon as one that is pluralistic and unanticipated, as opposed to unilateral and routine, in nature. Kusama’s surrealistic works were a convincing counterpoint to other performance-based video works that, revealed the power of sobriety and mundaneness. Bruce nauman’s familiar Pursuit (1975) unpacked the complexities of simple, repetitive actions–breathing, sweating, jiggling, and tiring–by filming them from a variety of angles, distances, and durations. Reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge’s nineteenth-century photographic investigations of human and animal movements, Nauman’s work prompted extended considerations of actions most viewers take for granted. In the end, these video works successfully reinforced the significance of institutional crisis, in which the “outer world” comes into the gallery, and in which conventionally private acts are rendered publicly. They also catalyzed a crucial and opportune meditation on the institutionis often strained relationship to unorthodox modes of contemporary artistic expression.

Marina Abramovic, Expansion in Space, 1977. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York.

Other works, particularly Marina Abramovic’s Expansion in Space (1977) and The light Surgeons’ Nuke Trac (2005) were less unassuming in their resistances to institutional containment and conservatism. Ulay and Abramovic’s physical clobbering of the white cube’s walls helped to illustrate how creative openness and spatial amplification come at the cost of self-inflicted pain and the disappointing realization that institutional boundaries may be pushed only so far. The light Surgeons’ video work served as an apocalyptic meditation on the total obliteration of space and humanity, as looped documentations of nuclear test explosions alluded to the unseen destruction of all familiar structures and frameworks. Along with these more conceptual examinations of institutions and their relationships with art and the body, the Bienal provided intriguing re-visitations of historically significant moments in documentation. Jonas Mekas’s Salvador Dali: Happenings (1964) and Andy at Work (1966-1971) explored film’s ability to reveal unique, latent perspectives of seemingly familiar artists and the performative relationships they maintained with their oeuvres. Other compelling television documentaries, including the Chilean Teleanalisis News Report (1984/1989), put into question what art truly is and where it is to be found openly inviting speculation on whether alternative “performances”(strikes, demonstrations, and uprisings) should be categorized as artistic gestures or practical, meta-institutional interventions. While the 2008 Sao Paulo Bienal successfully illustrated that divisions between art and everydayness remain as hotly contested as ever, it did little to connect these histories to the urgency of the contemporary moment and to initiate and sustain relevant dialogues with varied viewerships. This, coupled with the video lounge’s unfortunate placement in a headphoneless, unsoundproofed area where echoes of all videos could be heard at once, ensured that any conceptual glue the curators had envisioned for this area was lost to distraction and irritation.

The “open plan” on the second floor, the Bienal’s most contentious component, warrants discussion of the space and how it was initially described in the curators’ proposal as a “void” (later described in the revised curatorial statement as a “supposedly void territory”).10

“The Void” at The São Paulo Bienal, 2008. Photo by Royce W. Smith.

While Yves Klein’s Les surfaces et blocs de sensibilite picturale invisible (1957) and John Cage’s 4’33” (1952) set an avant-gardist precedent for the aestheticization of nothingness, Mesquita’s and Cohen’s void seems more closely aligned with imposed lack–lack of money, lack of cooperation, lack of trust. Rather than openly vetting the Bienal’s dire circumstances, the curators eclipsed them (or justified them) with references to lacan’s theorization of “suspension”11

and le Corbusier’s 1926 discussion of the “open plan” as a fundamental component of Modern architecture. Yet, this erudite, conceptual window-dressing of the empty space, euphemistically characterized in the exhibition catalogue as “fertile soil to highlight the powers of imagination and invention,”12 proved to be not so fecund after all.

On the night of the exhibition’s opening, approximately forty graffiti artists entered the empty second floor and tagged the walls with legitimate exclamations, such as “This is what art is” and “under dictatorship”– sentiments reflecting the outrage many paulistanos felt when they heard that vacant space would be displayed instead of works by Brazilian practitioners looking for the same visibility that participants in the first Sao Paulo Bienal–often referenced as the conceptual anchor of the 28th Bienal–enjoyed. led by guerrilla artist Rafael Pixobomb, the group–nicknamed “PiXacao: Arte Ataque Protesto”–wished to draw attention to the commodification of pichacao (graffiti) and the institutionalization of radical expression. While one might think that the group’s concerns resonated well with the curators’ visions for the democratization of empty, whitewashed space and an inclusion of the general public, stories abound of jailed fringe artists whose spray-painted frustrations and “dialogues” provoked the ire of the art establishment. Summarily dismissed by the Bienal’s administration as lawless vandalism, yet supported by many locals as timely acts of “poetic terrorism,”13 the often violent exchanges that night led to the online development of a “Manual for the Invasion of the Bienal 2008.” Assuming an anti-institutional stance with respect to cultural bulwarks like the Bienal, the publication elaborated on techniques that could be used to infiltrate the exhibition and “contribute” to the proceedings with graffiti and sticker attacks.14 Mesquita’s observation that artistic gestures are indeed unpredictable and “abstract” conflicted palpably and disappointingly with the “open plan,” in which the rules of exhibition were not only reified but intensified.

Graffiti Artist Instructional Graphics from the Anonymous Blog: “Manual Para A Invasão Da Bienal 2008.” http:manualparaainvasaodabienal.blogspot.com/

Cordoned off from the few works included in the Bienal, the third floor’s library space showcased the Wanda Svevo Historical Archive –a collection of biennale exhibition catalogues and selected museological scholarship. Access to information about now-defunct biennale traditions was a welcome inclusion, but its connection and applicability to the everyday viewing public was specious at best. The fact that relatively few individuals used the library mirrored similar problems with the Bienal’s conference and lecture proceedings–which were presented largely in Portuguese, poorly advertised, and insularly fashioned, yet umbrellaed with the hackneyed aim of “dialogue.” Much like the “Biennales in Dialogue” Forum hosted in Sydney in July 2008, the 2008 Sao Paulo Bienal’s dialogues remained cloistered within the ranks of those too intimately entangled with mega-exhibitions to dispassionately critique them or speculate on their uncertain futures.

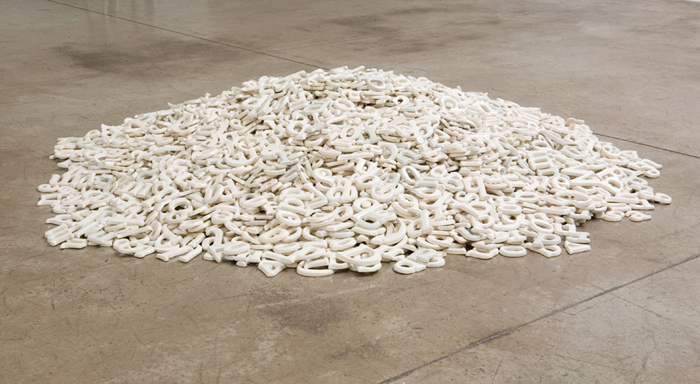

Valeska Soares, Catálogo (catalogue), 2008. Carpet and paper pulp letters. Dimensions vary. Image courtesy the artist, Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo, and Eleven Rivington Gallery, New York. Photo by Amilcar Packer.

Valeska Soares, Catálogo (catalogue), 2008. Carpet and paper pulp letters. Dimensions vary. Image courtesy the artist, Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo, and Eleven Rivington Gallery, New York. Photo by Amilcar Packer.

Yet, some of the third floor’s works helped to counterbalance these exclusive activities, including Erick Beltran’s The World Explained (2008)–an ongoing encyclopedic collection of descriptions, maps, diagrams, and flowcharts that provided “answers,” from the perspectives of non-specialist exhibition attendees, to questions born of seemingly simple objects, systems, and activities. For example: How is a war decided? What is intuition? Attendees’ “answers” subsequently formed part of a contemporary rhetorical collection of meanings that, much like Wikipedia, muddy the clarity and straightforwardness of both question and answer. Unlike the familiar eighteenth-century Wunderkammer, in which segregated compartments aid with a taxonomic organization of knowledge, Beltran’s works arranged responses palimpsestically; each interpretative layer revealed fluctuations in perception and meaning dependent on mood, perspective, and circumstance. The work linked powerfully with other configurations of the Wunderkammer presented in the exhibition, as illustrated in Mauricio Ianes’s Untitled (The Kindness of Strangers, 2008). Staging a performance that started shortly after the Bienal’s official opening, Ianes stood silently, motionlessly, and nakedly in various parts of the pavilion over the course of the exhibition and simply waited. He waited for clothes; he waited for food–an act that exposed not only an artificial state of hardship (since the artist stated he would “pull the plug” if he felt endangered during the course of the piece), but also the conundrum of why strangers felt comfortable providing copious offerings in a gallery setting, as opposed to the street where generosity is most needed. As Ianes amassed more goods and displayed every gift he received (from condoms to phone numbers to shaving cream), deprivation transformed into a visible material plenty–the moving consequence of an abundance of quirky exchanges between artist, viewer, and environment.

Maurício Ianês, Untitled (The Kindness of Strangers), 2008. Interactive performance, 28th Bienal de São Paulo. Image courtesy the artist. Photo by Annie Strader.

Disappointingly, though, nearly all of the third floor’s works were canvassed against or displayed within Colombian artist Gabriel Sierra’s plywood structures–what he called “continents.”15 Sometimes objects in their own right and sometimes accompaniments or backdrops to other artists’ expressions, Sierra’s work exuded a monotonous, poorly crafted crudeness that frequently interfered with or utterly overshadowed the potential messages and impacts of other pieces. But repetition successfully made for the mainstay of the third floor in Allan McCollum’s Eighteen Hundred Drawings (1988-1991), in which a sea of Rorschach-like abstract works bombarded the viewer with a sense of sameness; closer inspection revealed the intricate detailing that rendered each framed work unique, special, and significant–despite being one expression amongst many others. Such artistic, structural, and presentational liberties and experimentations buttressed the tenuous conceptual architecture of an exhibition somewhat unsure of itself–often questioning its legacies and revealing an organizational rudderlessness when compared to the more orthodox Sao Paulo Bienal staged in 2006. Veleska Soares’s installation Catalogue (2008) was created by rendering in paper pulp each letter contained within the first Sao Paulo Bienal’s catalogue and unceremoniously dumping the resulting pile of three-dimensional characters on a carpet patterned after the catalogue’s cover. The work brought the 2008 exhibition’s contemporary focus back full circle to the lofty ambitions of the first Bienal staged in 1951–an exhibition that aggressively sought out the lynchpins of Western Modernism and subsequently used the Bienal to re-orient the art world’s attentions away from Europe and the united States. While Mesquita claimed that the Bienal had accomplished what it first intended to do, Soares used her work to insist on the impending failures of rigorous exhibition and cultural engagement to resuscitate the Bienal–characterizing that first manifesto-like catalogue as “the book/object that is becoming an object of desire as it loses its function.”16 ultimately, the work of literal deconstruction exposed the uncertain legacy of the Bienal that now must serve as the basis for contemplating its future prospects as either reconditioned and relevant or extraneous and untenable.

Allan Mccollum, Eighteen Hundred Drawings, 1988-1991. Graphite pencil on museum board. Dimensions vary. Image courtesy the artist. Photo by Amilcar Packer.

Navigating an almost-imperceptible divide between what Johanne lamoureux might describe as the anchoring “place” of the exhibition and the ghostly “trace” left by virtue of its absent, expected elements,17the 2008 Sao Paulo Bienal was far from the “non-exhibition” many expected it to be. Its risk-taking was rewarded with response and reaction, albeit not always the structured and cerebral dialogues that the curators seemed to want to solicit and initiate. Its shoestring budget still allowed for the types of relational activities that make biennials the centripetal forces that attract people who might not otherwise be drawn to the pomp of museums and galleries. In retrospect, the Bienal’s greatest setbacks stemmed from an unwillingness to confront head-on the ugly political maneuverings and machinations that led to its moment of crisis, as well as a tendency to overstate and embellish a conceptual agenda that never truly came off as inspired, authentic, or credible. The Bienal sadly concealed its sufferings with the hope of earning approbation that might be forthcoming from associated conferences, invited plenary lectures, newspaper-like publications, and morning talk shows conspicuously setting up Oprah-like audiences to fill and marvel at (rather than ridicule) the “void.” The curators may well have masked the monumentality of the institutional and bureaucratic obstacles they faced with a business-as-usual bravado, but sometimes the public enjoys the suffering hero and accepts the associated moments of indecision and vulnerability–not as the resulting spectacle of the art world’s dirty laundry, but as the unavoidable aftermath of honesty. If only the Sao Paulo Bienal had suffered a bit more honestly.

Royce W. Smith is Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at Wichita State university. Earning his Ph.D. at the University of Queensland in 2005, he has been an active critic of contemporary festivals and biennales and recently co-chaired a session on the future of mega-exhibition at the Association of Art Historians annual conference at Tate Britain.