Feminism has returned with a vengeance to the art world. Events just in the past two years range from the 2005 Venice Biennale, with its feminist theme; the large-scale exhibition of feminist art at the Migros Museum in Zurich in 2006; It’s Time for Action, and the ambitious Kiss Kiss Bang Bang: 45 Years of Art and Feminism, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Bilbao (2007); to the two large-scale exhibitions in the USA this past year –Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and Global Feminisms at the Brooklyn Museum (an exhibition that opened in tandem with the new Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the museum). In addition, numerous spin-off or critically interventionist exhibitions organized at commercial and community galleries counter the narratives posed by these major venues,1 and countless articles in the popular and art presses have been published (including the March 2007 issue of Frieze, and the February 2007 issue of Art News, entitled “Feminist Art: The Next Wave”).2 Academic feminist art history and theory have also been actively revived. A number of major exhibitions and conferences rethinking the history and even concept of feminist art–such as, the important exhibition Gender Battler at the Contemporary Art Center in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, the Girl on Guy exhibition at A+D Gallery, Columbia College of Chicago, and, over 2007 and 2008, conferences in South Africa, Los Angeles, New York, and Stockholm (among other places around the world).3

All of this renewed interest in feminist art–both historical and contemporary–makes me nervous. While to a greater or lesser extent, academic institutions, university and community art galleries have sponsored and supported feminist work in and on the visual arts (from studio practice to feminist art history) since the rise of the feminist art movement, it is only now that the commercialarms of the art world are seemingly obsessively interested in historical and contemporary feminist art. Why, after a decade and a half of rhetoric about the “death” of feminism and “post-feminism”, has the international art world suddenly embraced feminist art with an enthusiasm that goes far beyond its tepid and spotty reception of it from the 1970s through the end of the twentieth century?

Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art (book cover), Edited by Maura Reilly and Linda Nochlin, (London, New York: Merrell Pub. Ltd., 2007).

New York-based artist Charles Labelle has, like many, responded to the exhibitions with cranky cynicism Of Global Feminisms, which includes only work from the past 15 years, he notes, “Feminism now seems to be all about lots of girls re-claiming the right to act hysterical, sell their bodies or play dead.”4 Labelle’s comment exemplifies one common attitude towards feminism in the art world since the early 1990s, with the spate of “bad girl” exhibitions that sprung up on the coasts of the U.S. around that time.5

As this view has it, the art world fervor around feminism is about marketing a kind of bad girl or, in the words of Ariel Levy, “raunch” feminism that is perfectly in line with the antics of MTV culture, soft core pornography, or reality television, where younger generations of women purvey themselves as overtly and highly sexualized ostensibly as a way of claiming cultural power.6 The art institution’s renewed interest in exhibiting feminist art, viewed along these lines, then, is aimed at nothing more than making money out of the bodies (and bodies-of-work) of women. Of course the question is whether these women are selling out feminist goals, selling themselves too cheaply, and/or conflating their bodies with art in such a way as to produce the body itself as an image that circulates without referent–an image that is essentially the same in value as the money that is exchanged for it. The market, then, is a key motivator behind the spate of exhibitions and magazine issues highlighting feminist art. There is no question, I would argue, that what little gap could be imagined between making art or writing about it and selling it in around 1970 has been collapsed.

Even shows posed as being more intellectually and politically driven, such as “Wack!” (one of a long string of exhibitions mounted by the Museum of Contemporary Art, each of which purports to deliver a comprehensive history of a movement, from Conceptualism to Performance Art), are motivated in part by market concerns. Shows such as “Wack!” are marketed as elaborate social events, positioning curators and the institution itself as authoritative in narrating a particular, and generally quite conservative and “safe,” institutional history of contemporary art. While this dynamic does not entirely negate the supposedly intellectual and political interests voiced by curators and writers who seek to reaffirm the radical politics developed in the feminist art movement in the 1970s, it must be stressed along these lines that all of us writing about and exhibiting art under the rubric of feminism are participating in a broad scale PR campaign that packages feminism as a commodity to be bought and sold (and, very soon no doubt, to be rendered obsolete once again).7

There is another crucial pressure that has been as far as I know completely overlooked in discussions about why feminism is of sudden interest to the international art world–the destruction of the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon in the United States on September 11, 2001. 9/11–the violent and apocalyptic destruction of the USA’s phallic monuments to its economic and political dominance in the world–is the hole that rips the past from the future, not only in the American imaginary but in the lives, belief systems and social structures of all the other cultures affected by American aggression since that date, cultures stretching from those of Afghanistan and Iraq to those within and across the borders of the USA seen as “suspicious” by the increasingly powerful right wing–such as intellectuals, queers, and people with brown skin who might appear to be “Arab” terrorists. In light of these explosions of violence, which have shattered everything from bodies, to cities, to belief systems (including conceptions of what matters in terms of identity politics), scholars, artists, intellectuals, and other creative people wishing to stop the terror and oppression have found ourselves at a loss.

The recuperation of feminism in art discourse and institutions is, I am arguing, in part about a desire to return to, and take wisdom from, the most successful political movement within the visual arts in the past 50 years. This need to define an effective mode of political intervention in the face of global networks of power that seem inexorable and impossible to break down is, I am suggesting, what drives the sudden motivation to look back to a loosely defined movement that we at least fantasize as offering the most effective institutional and visual strategies in countering these nefarious structures of power–a movement that, in retrospect, seems to have stemmed from a kind of conviction we can now only dream about retrieving. This drive to recuperate past activisms as a means of finding a way to be political in the present is poignant and acute. As Los Angeles-based artist Susan Silton noted to me, “Whatever is fomenting among younger feminist artists is happening simultaneously with, and perhaps in response to, the global mess that has September 11 as some kind of marker.”8

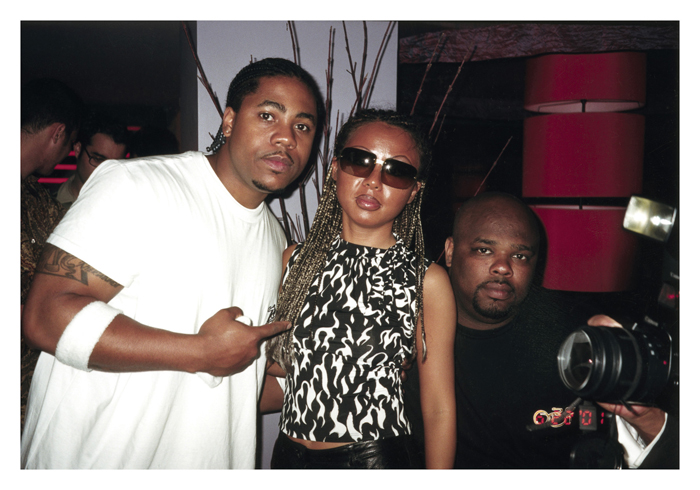

Nikki S. Lee, The Hip Hop Project (15), 2001. Digital Fujiflex c-print; 21-1/4 x 28-1/4 inches, Edition of 5; 30 x 40 inches, Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Bringing a critical perspective to the resurgence of interest in feminism is not, however, the same as downplaying its importance. To the contrary. In a recent issue of Artnews on feminist art, Jori Finkel cites Nikki S. Lee, a younger US-based American artist, as stating about feminism:

I’ve never had to think about the problem. I don’t like the idea of bringing up the issue. The more I bring up the issue, the more I feel like I’m the one separating men from women. In Korea I didn’t even hear about the feminist movement, so I grew up without the concept…I grew up in a family where I was treated fairly. In New York, too, I have never been treated unfairly.9

Lee’s willful flaunting of her ignorance about the stakes, aims and histories of the feminist movement is startling. It illustrates the dangers of assuming that all that exists is where we are right now, and that we know what we see. Lee does not seem to recognize that she would not be able to make the work that she has produced were it not for the generations of feminist artists, activists, and theorists working hard to create that welcoming space for her work to be viewed and understood. If she feels she is “treated fairly,” her debt to previous feminisms is all the greater.

Exploring the recent return of feminist art to public view, then, I am struck by how important it is once again to tell the histories of previous feminisms. To that end, it is worth casting an admittedly partial glance back to the late 1960s and early 1970s to explore filling the void with at least one variant of how this “past” might be retold from the present point of view. The feminist critique of Western models of viewing was central to the rise of feminist visual theory in the 1970s. The European Renaissance notion of human individuality was instrumentalized in relation to painting and architecture by theorists such as Leon Battista Alberti, who theorized a model of perspective that positioned the painter, architect, and viewer at the apex of a cone of vision.10 Effectively, this produced a subject of vision and knowing who was centered in visual knowledge. This subject was implicitly a white male subject of a high enough class to situate himself in such a privileged position of seeing and knowing. The power of this implicit, mythical subject (never of course attained in full by actual individuals) reached its apogee in the modern period in figures such as the modernist artistic genius even as it began to break down as a concept and belief system under the pressures of colonialism and industrialism. However, this mythical figure (or, more accurately, concept) came to dominate feminist critiques of the “male gaze” in the 1970s.

John Berger’s and Laura Mulvey’s theories of the male gaze thus aimed to denaturalize and dismantle the structures positioning the male subject at the apex of the cone of vision, so often (they argued) empowered in relation to the naked bodies of women so common in European painting traditions since the Renaissance. Mulvey famously deployed Freud’s theory of fetishism in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” to argue that the male gaze, as instrumentalized in Hollywood cinema, functions to produce that which we fear as other. The filmic image plays on the originary loss–the fear of castration–suffered by the viewer, promising to redeem or palliate this loss through fetishizing the female body as object.11

Following on Mulvey’s observations, it is clear that the body is the key factor in Western imaging and visual theory. Michel Feher’s Foucauldian formulation about the meaning of the body in contemporary life situates it precisely as the pivot through which any politics must be articulated in contemporary culture:

The body is at once the… actualizer of power relations–and that which resists power…. [I]t resists power not in the name of transhistorical needs but because of the new desires and constraints that each new regime develops. The situation therefore is one of permanent battle, with the body as the shifting field where mechanisms of power constantly meet new techniques of resistance and escape. So the body is not a site of resistance to a power which exists outside it; within the body there is a constant tension between mechanisms of power and techniques of resistance.12

For feminists, the body, which was the vehicle through which women could be objectified but also through which women could access their own social and political agency, became the battleground in two ways: the struggle for rights in relation to broader cultural norms, and in articulating debates about power and strategies within feminism itself. From the early 1960s onwards women artists such as Carolee Schneemann and Yoko Ono explored the interrelation between the female body presented as object and that body enactedas a subject with agency. It is important to emphasize that the body itself, whether enacted live or represented photographically, cinematically, or videographically, was the crucial pivot for this kind of feminist work.

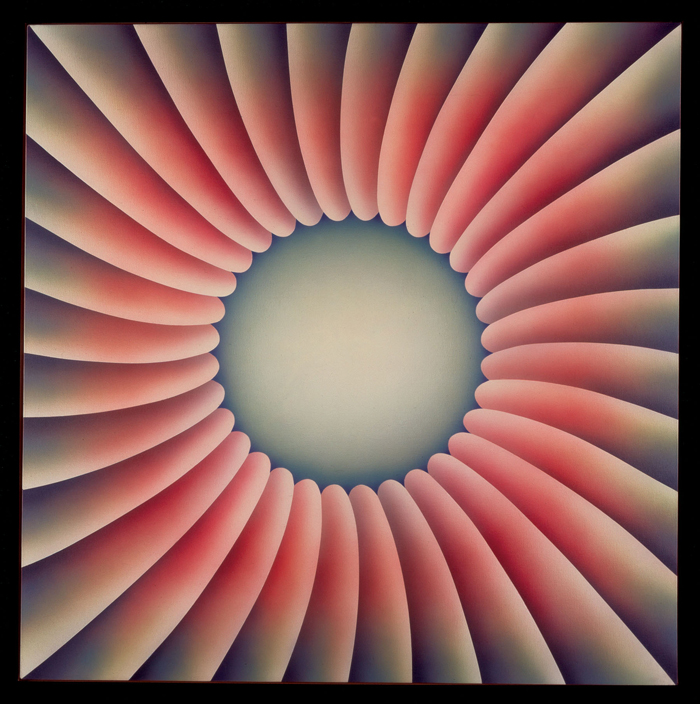

Judy Chicago, Through the Flower, 1973. Sprayed acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 inches. Collection of Elizabeth A. Sackler, New York. Photo: © Donald Woodman. © Judy Chicago, 1973.

The attempt to reverse or at least mitigate the negative effects of the oppression of women in general, but also in the art world and in canonical histories of art, with their legions of objectifying images of women, was made more explicit by about 1970 in the work of artists such as Judy Chicago and Adrian Piper. In works such as Peeling Back (from the “Rejection Quintet,” 1974) Chicago addresses in a literal sense the way in which patriarchy constructs the female body as a void. Focusing on the cunt, she returns its “presence,” its significance as a sign linked to material flesh. Piper, in contrast, in the early 1970s Catalysis series, keeps the body clothed, refusing to unveil herself before the public gaze she solicits, adopting repulsive clothing and smells as a way of pointing to and exacerbating her othering by her culture. Performing herself as overtly other, and excessively so, she takes on agency–the agency to repel.

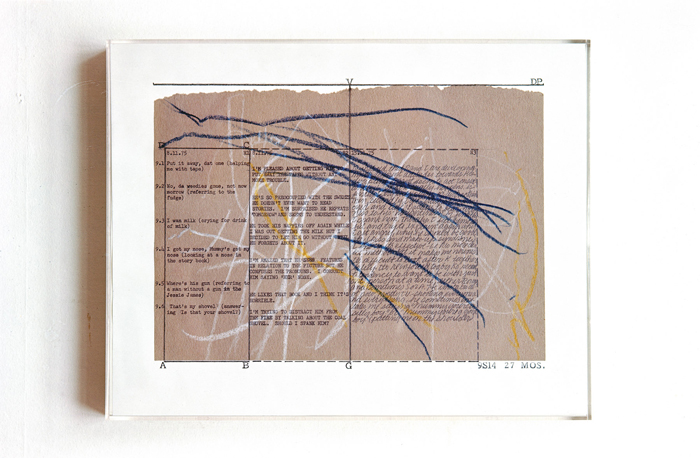

Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document: Documentation III, Analysed Markings and Diary perspective Schema, 1975 (detail). Perspex unit, white card, sugar paper, crayon. 1 of the 10 units, 35.5 x 28 cm each. Collection, Tate Modern, London.

As early as the mid 1970s, however, the body began to go underground or to be rejected as a visible pivot around which feminist practice could or should be articulated. Particularly in London and New York, feminist artists and art historians such as Lisa Tickner, Griselda Pollock, Sandy Flitterman, Judith Barry, and Mary Kelly articulated a theory of feminist visual practice that repudiated the representation or staging of the female body under the grounds that such strategies of making the body visible inevitably reproduced the structures of fetishism. As Kelly put it, when artists such as Judy Chicago attempt to valorize the woman’s body, “[u]sually the artist uses herself as signifier, as object, and of course necessarily [therefore] as fetish.”13 Griselda Pollock and Kelly in particular articulated a theory of feminist practice that called for the avoidance of representing or performing the female body, thus repudiating fetishism through the adoption of strategies of shocking or distancing the viewer drawn from the theories of Bertholt Brecht. This idea, which became dominant not only in feminist but in postmodernist practices in the 1980s in the Euro-American art worlds, was activated in the work of highly visible artists such as Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman.

As suggested with the comparison between Kelly’s and Chicago’s approaches, 1970s and 1980s feminist art discourse was overdetermined by debates about the body, debates often posed and/or perceived as polarized into “essentialist” and “anti-essentialist” camps. The so-called “essentialist” feminists (usually identified with the West Coast of the US and/or with figures such as Judy Chicago and Lucy Lippard) supposedly based their work and theories on a concept of an “essential” femininity linked to the anatomical female body; the “anti-essentialists” (linked to Griselda Pollock, Mary Kelly, and others working in London and New York) tended to argue in favor of the idea of a constructed and contingent femininity. Both “sides” of the debate often caricatured the other.14

However, those who argued in favor of representing or performing the female body as a means of reclaiming agency and those who prohibited the mobilization of the female body as necessarily fetishistic were not as diametrically opposed as they often perceived themselves as being. In retrospect it is clear that both the “essentialist” feminists such as Chicago and the “anti-essentialist” feminists such as Kelly shared certain assumptions. Both, for example, continued to work from oppositional models that ultimately devolved back to the concept of masculine power and a belief in the inexorability of structures of fetishism or, more broadly speaking, of objectification. Both tended to prioritize gender as a separable category of human experience–as one not necessarily conditioned or affected by other identifications such as race (although, it must be said, Kelly and Griselda Pollock were adamant about theorizing gender in relation to class–but until Pollock’s work in the 1990s, neither addressed race and ethnicity).

While these artists often supplied their own impassioned theories, such as Kelly’s important essays and interviews from the 1970s and 1980s or Chicago’s important essay “Female Imagery” (1972), co-authored with Miriam Schapiro,15 there was in fact a larger theoretical context for such work that explains the tendency to assume a binary logic of gender and to ignore the intersectionality of gender with other aspects of identification–a paradox given that the two most influential theories of identity in the immediate post WWII period both theorized racial difference (and one specifically in relation to gender difference): Simone de Beauvoir’s 1949 The Second Sex, translated into English and widely disseminated in North America with its translation in the early 1950s, and Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin White Masks of 1952. Both Beauvoir and Fanon drew on Hegelian theory–particularly the model of the Master/Slave relation–to explore similar issues of structural and conceptual discrimination. Beauvoir explicitly shifts Sartre’s neutral description of an “existentialist ethics” whereby the “subject” throws himself into being, transcending his immanence and accepting responsibility for his agency in the world, exploring the fundamental gender bias built into this system:

Every individual concerned to justify his existence feels that his existence involves an undefined need to transcend himself, to engage in freely chosen projects…. Now, what peculiarly signalizes the situation of women is that she–a free and autonomous being like all human creatures–nevertheless finds herself living in a world where men compel her to assume the status of the Other. They propose to stabilize her as object and to doom her to immanence since her transcendence is to be overshadowed and forever transcended by another ego…which is essential and sovereign.16

Even as Beauvoir theorized the othering of woman through a master/slave logic that functioned to produce man as “sovereign,” so Fanon described the experience of living in France with a body perceived as racially other: “Sealed into that crushing objecthood, I turned beseechingly to others…the glances of the other fixed me there, in the sense in which a chemical solution is fixed by a dye…. I burst apart. Now the fragments have been put together again by another self.”17 The poignancy and power of these models lay in part in the brilliant way in which they took existing dominant philosophical ideas–the self/other structure initially defined in Hegel and refined and expanded within existentialism–and, with a passion and eloquence born of a sense of personal political urgency, noted that this dichotomy is never neutral but, in fact, highly charged in terms of perceived identifications linked to the body being othered. The primacy of visuality in these models of self and other indicates the importance of visual arts theories and practices to any conceptualization of how structures of identification function culturally.

This oppositional model of self and other, posed through a model based on the visibility of gender, sexual, racial and/or ethnic identity, deeply informed post- 1960s identity politics as they came to be formulated in European and North American culture, and it cannot be underestimated the degree to which these politics were profoundly, and structurally, binary in their logic. The complementary models developed by Berger and Mulvey of the gaze as empowered with that in its purview as passive, objectified, fetishized, are no exception. However, due to the explanatory force of Berger’s and Mulvey’s ideas, particularly Mulvey’s, these arguments became hegemonic in feminist art discourse by 1980, discourse that (via Mulvey’s theory) centered on a model of a unidirectional male gaze that feminists must aim to thwart or reverse in some way.

As Griselda Pollock argued in her influential 1988 essay “Screening the Seventies: Sexuality and Representation in Feminist Practice, a Brechtian Perspective”:

In place of the utopian claims for personal expression and universal understanding by means of the power of the material or medium of art forms typical of modernist theory, feminist materialism recognizes a textual politics–an interrogation of representation as a social site of ideological activity….. [Brechtian distanciation] is not a style or aesthetic gambit but an erosion of the dominant structures of cultural consumption which… are classically fetishistic.18

While these strategies pivoting around fetishism (the crux of Mulvey’s arguments) were not the only ones in play in feminist art and theory from the 1970s and 1980s, they were dominant, particularly in New York and London. And for Pollock and other feminists drawing on theories of fetishism to propose a feminist practice that thwarted its conventional structures of objectification, the work of Mary Kelly–an American working in London for most of the 1970s and 1980s–was exemplary. Deeply informed by Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis, as well as Marxist theory, Kelly’s work, as Pollock argues, exemplifies the mandate for feminist critical practice in the visual arts to “resist… specularity [i.e., the visual pleasure afforded to the male gaze] especially when the visible object par excellence is the image of woman.” As Pollock continues in a prescriptive vein, feminist art “has to create an entirely new kind of spectator as part and parcel of its representational strategies,” something Kelly’s 1979 Post-Partum Document and the 1991 project Interim fulfill in an exemplary way, according to Pollock.19By continuing to pivot around the model of fetishism and the feminist critique of the male gaze, Pollock’s model of feminist critical practice, as well as Kelly’s work, provided a crucial and influential theory of feminist art–but one that continues to work within a binary logic of gender difference established by Beauvoir around 1950.

Valie Export, Tapp und Tastkino, (Tap and Touch Cinema) 1968. Gelatin silver print; 78 x 87 cm. Edition: 1/5. Courtesy of the artist and Charim Galerie.

However, other artists deployed the female body in live settings to pervert or refuse a simple binary even as early as the 1960s. Working with and in relation to the female body, artists such as Valie Export and Yoko Ono deliberately exaggerated the binary, effectively exploding its rigid logic–such as in Valie Export’s two major projects from the late 1960s, Tap and Touch Cinema (1968) and Genital Panic (1969). Tap and Touch Cinema actualized the physical “touch” implied as the desired goal of the male gaze, thereby collapsing the distance between the gazer and the gazed at. This collapse of distance became highly threatening, because fetishization takes its power as a structure of objectification from precisely this distance. Not only does Export gaze right back at the ogling and fondling male participant; he is also “looked at” by the crowd around him and thus himself becomes an object of the gaze, which is made public rather than (per the structures of fetishism) private and so erotically charged.

Export’s Genital Panic makes the effects on women of the violence of the male gaze even more explicit, with Export famously exposing the exact endpoint of an objectifying gaze, the cunt, while sporting a threatening gun and frighteningly excessive head of hair. This, of course, is another means of defeating the logic of the male gaze, which (again) relies on the invisibility of the supposed goal of its trajectory of power: the very cunt that (per Freud’s theory of fetishism) is argued to be a “lack” rather than a moist and fleshy “presence.” As a visible mound of flesh, the cunt as it were looks back at the gazer, completely perverting the logic of fetishism.20

It is notable that, with a few exceptions, neither live art in which the body was exposed, nor representational cunt art (exemplified by Chicago’s Peeling Back), were taken up as strategies by women of color in the United States or Europe. Lorraine O’Grady, an African American artist and writer, has explored this issue in her important essay “Olympia’s Maid,” where she notes that the body of the Black woman is “always already colonized…raped, maimed, murdered” or erased from consciousness, while still, like the Black maid in Manet’s 1863 painting Olympia, functioning in the visual field to throw the white woman’s body in relief such that “only the white body remains as the object of a voyeuristic, fetishizing male gaze.”21

Exceptions to this tendency were the works of two Japanese artists in New York, Yoko Ono, with her groundbreaking mid-1960s Cut Piece, in which she encouraged the audience members to cut off her clothing and to expose her body to view, and Yayoi Kusama, who performed her body in urban space (particularly in New York City in the late 1960s) as a way of gaining visibility for herself as a woman artist but also flaunting herself as a body worth looking at, thereby gaining attention for her visual art work. Kusama produced a body that was ambiguous in terms of its feminism–a very early example of the kind of brazen, self-sexualized body that came to be identified in the 1990s with “post-feminism.”

This points once again to a troubling myopia within feminist art debates and practice in the 1970s through the 1990s: it was largely the white woman’s body that was at issue in critiques of fetishism in the 1970s. There were of course exceptions, such as O’Grady in both her writing and art practice, Adrian Piper, whose work was noted above, and Ana Mendieta, an artist born in Cuba and brought to the U.S.A. as a child. Mendieta’s practice deployed her own body, effectively exposing the confluence of racial and sexual fetishism–as in her important Siluetaworks from the 1970s, which either literally (through the presence of her body) or figuratively enact the female body as a mark or wound on and in the earth via rituals touching on the syncretic traditions of Santeria to which she was exposed as a child.

The live or otherwise performative body, I am suggesting, is the point around which gender-critique in the visual arts has been articulated since the 1960s. Hannah Wilke, Gina Pane, and Jo Spence, for example, performed their bodies in order to explore a wounded and ill femininity–enacting the seemingly inexorable link between the female body and suffering. Wilke and Pane confronted viewers with live acts that ruptured their flesh symbolically (Wilke) or literally (Pane) while Spence, as if anticipating Wilke’s later self-imaging while in the throes of cancer treatments, performed her scarred body after a mastectomy for a series of photographic images, pointing to a mode of performative photographic self-imaging that came to be well known in the 1980s through the work of Cindy Sherman in the U.S.A.

But others also took up the camera as a means of staging their bodies to exaggerate and/or confuse cultural codes of gender and sexuality–such as Urs Luethi and Manon in Switzerland. While Cindy Sherman always appears as a masquerade of femininity, in Luethi’s and Manon’s work there is no binary gender category one can deploy to make sense of these complex characters–they are transexualized characters, with no securely gendered body as referent to pin down where they fall in the binary male/female (Manon, who is a woman, for example, often seems in her recent work to be playing a man in drag). This mode of performative self-imaging became common in the 1980s and following. Thus, artists from Yasumasa Morimura (who has performed himself as queerly feminine in a number of works spoofing art history in the 1980s), to Del Lagrace Volcano, a self proclaimed “gender variant visual artist” who documents his own and others’ cross-gendered self performances, Mariko Mori, and Renee Cox articulate bodies that are not only gendered (or cross- or trans-gendered) but simultaneously aggressively raced, classed, and otherwise identified.

Paradoxically through its extraordinarily powerful impact on the artworld, feminism thus became increasingly contested and attenuated around 1990. By expanding, crucially, on what feminism could be politically–with the rise of debates about its myopia in terms of addressing class, race, and other identifications as well as broad issues of globalization–debates surrounding feminist art either diffused into more general discussions about identity, on the one hand, or, on the other, degenerated into dismissive or flippant journalistic claims that feminism had run its course, as signaled by the common use of the term post-feminism. Artists in the 1990s, such as Sue Williams and Tracey Emin, were labeled post-feminists; they took their cue from earlier feminists such as Kusama (though, sadly, much of Kusama’s work had been long lost to view) and from a rising celebrity culture of sexualized yet seemingly powerful women performers such as Madonna to produce angry, explicitly self-sexualized narratives–often conflating abjection and power as equally at issue in the complexities of women’s sexual identities and experiences. The way in which such strategies dovetailed with the inexorable forces of capital was made clear by the late 1990s and following with the rise of reality television and almost parodic versions of the Madonna-esque femininity among completely vacuous celebrities–from Posh Spice to Paris Hilton–with no talent or apparent cultural power other than the attraction they could hold by flaunting their bodies to the media.

Sue Williams, Detritus, 2007. Oil on canvas; 70 x 70 inches. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York.

This trend has reached what is, for many feminists of my generation and earlier (I was born in 1961), a bizarre and disconcerting apogee in the works of younger generation white women artists such as Australian Anthea Behm (b. 1977) and American Liz Cohen (b. 1973). Extravagant claims are made for these artists as somehow taking apart or critiquing myths about female subjectivity. “In The Chrissy Diaries,” Timothy Morell argues, “Anthea Behm catalogues the female archetypes that girls dream of becoming when they grow up, but she portrays them with poignant disillusionment. The short film clips of Chrissy (played by Behm) fulfilling her fantasies don’t quite match the glamorous images a little girl might imagine.” And Cohen’s work is part of a larger project, BODYWORK, which involved her simultaneous transformation of her body (via a personal trainer) into a bikini model and rebuilding of a German Trabant into a lowrider American car; the results are entered into lowrider competitions. While the work is conceptually interesting in Cohen’s co-articulation of herself as a car customizer and bikini model (the “masculine” and “feminine” positions conflated in one subject), both positions are resolutely normative (white, heterosexualized, conforming to gender stereotypes) and they remain binary; furthermore, the visual images of Cohen’s lush, predictably ideal, young, white, thin body become simplistic repetitions of bad advertisementsfor cars–and nothing, sadly, shifts the images from reiterating exactly the fetishistic structures Mary Kelly warned against replicating.

Anthea Behm, The Airhostess from The Chrissy Diaries, 2005. Still from synchronized four-channel video installation (parachute by parachutes for ladies), 36 min 56 sec loop.

I would argue that such recent practices seem to appropriate strategies from earlier feminisms without sustaining the politics these strategies aimed at promoting. And the strategies are replicated either without knowing of the earlier models or by knowingly repeating them, but in new contexts in which they do not have the same political effect. The circuits through which images of self-display travel in 2007 are vastly different from those active in the 1970s–a woman artist today can’t simply redo Hannah Wilke’s photographic self-imaging strategies, which around 1975 arguably functioned to ironicize the habitual fetishization of the white woman’s body in Euro-American culture.Looking at Behm’s and Cohen’s pictures I feel a profound sense of melancholy about the lost utopianism of the feminism I knew and loved as I came of age as an art historian in the late 1980s. They indicate that the art world might have reached an impasse in relation to feminism. But, I insist, this is an impasse only if we persist in understanding feminism in terms articulated twenty or thirty years ago. I will end this paper by suggesting that, viewed from a different point of view, the legacy of the extraordinary political shifts engendered by the efforts of artists and theorists working under the banner of feminism from the 1960s through the early twenty-first century can be viewed more optimistically.

Liz Cohen, Trainer, 2006. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Laurent Godin

(Paris).

Liz Cohen, Hood, 2006. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Laurent Godin (Paris).

Liz Cohen, Air Gun, 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Laurent Godin (Paris).

Para-Feminisms: Positional Politics 2007

If nothing else, feminist art practice and theory since the 1970s has proven the inexorable way in which the body is always already gendered, sexed, and raced. The body is always already in representation, even when presented “live.” So much is made explicit in the work of artists working today in ways that highlight the social and political positioning of bodies in relation to how they are identified–and this highlighting is precisely what I am arguing we can still link to the legacy of feminisms–via what I want to call a politics of positionality.

A politics of positionality is complementary to my concept of parafeminism as articulated in my recently published book Self/Image: Technology, Representation and the Contemporary Subject. Deploying the term parafeminism, I argue that the most important legacy of feminism is a broader articulation of a politics of positionality across the field of the visual. This politics continues to pivot around the body, but not as a “ground” to be either positively rendered and performed, or critically dismantled, or shielded from a fetishizing gaze–but as a lived and living manifestation of the political effects of being variously positioned (identified) in today’s global economies of information and imagery.

Positionality, then, is definitively not meant to imply a fixed locus in space, a determinable “identity,” or even an identifiable site in relation to ideology. It is indicative of the way in which we continue to “identify” ourselves and others in relation to perceived and complexly interwoven identifications. Positionality is constantly in motion, articulated across social space, diffuse. As I am imagining it here, parafeminism, with this politics of positionality, understands “gender” as a question rather than an answer–and a question that percolates through other subjective and social identifications–sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, nationality, and so on which can never be fixed but always take meaning in relation to each other.26

What is new about what used to be called feminism and now (I am suggesting) might need to be called something else is precisely the freedom anyone now has to articulate sexual power in a way that does not necessarily align with a binary logic of male and female. This freedom (which is continually constrained, perverted and appropriated by the marketplace, and is only ever relative) is available because activists and purveyors of culture, visual and otherwise, from the 1950s onward laid the ground for subjects identified as female to begin to break free from their exclusive identification in heteronormative patriarchy with their sexuality (in Freudian or Mulveyan terms, as objects of male desire).27

As cited above, Michel Feher makes a Foucauldian argument that “the body is at once the… actualizer of power relations–and that which resists power….”28 In a culture of visuality such as the modern West, the body becomes visualized as an object of an empowered gaze via fetishism or, as Michel Foucault points out, in the modes of surveillance through which Euro-American subjects are encouraged to internalize our own objectification.29 In a patriarchal and racist culture of visuality, this internalization of the “being seen” has different valances for different subjects. I would stress that the shift from modernism to contemporary globalized late capitalism is one characterized by the degree to which we have internalized our own objectification –particularly those of us identified as women, blacks, lower class, immigrant, queer, or otherwise “other” to regimes of power. Simply reiteratively imaging ourselves to externalize the forces of objectification (per Behm or Cohen) only reinforces the intertwined structures of all fetishisms: sexual, racial, visual, and economic. These practices come across as outmoded in their singularity, in their focus exclusively on a thin, white, young ideal, and disturbingly reactionary in their return to previous modes of presenting the female body as if it can be definitively known–and so owned either by the person identified with it, or by the person who gazes at it.

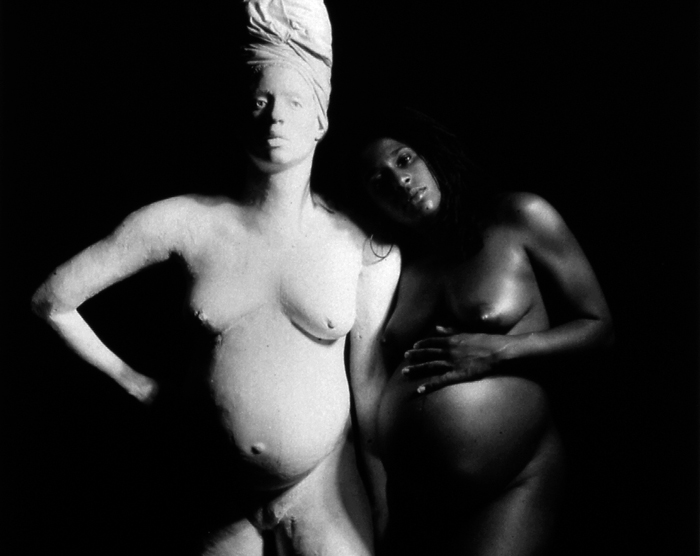

Renee Cox, Yo Mama and the Statue, 1993. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy Von Lintel Gallery, New York. © Renee Cox.

What I am interested in, finally, are works that I experience as offering something far more radical, and far more attuned to the ways in which we navigate the complexities of global late capitalism–parafeminist works that emphasize a politics of positionality, in which the body is both visualized and enacted but impossible to know. Works such as Cathy Opie’s Self-Portrait Nursing (2004), which depicts her large dyke body breastfeeding her son; Jenny Saville’s recent paintings of cross-gendered bodies, rendered in lush brushy style from awkward points of view; Karolina Wysocka’s loving portrait of the male body (a close-up video loop of a pulsating scrotum, from 2006, entitled Jewel); Renee Cox’s use of her statuesque Black body to push the limits of the West’s fetishism of the female body in works such as Yo Mama! from 1993. These practices both remind us of the force of the body to maintain as well as to resist modes of power and denaturalize how the body, when performed or depicted in the visual field, is experienced and interpreted in terms of a complex web of identifications. In doing so, I am arguing, they maintain what I feel is the most crucial legacy of the feminisms of the 1960s and 1970s: the insistent exposure of circuits of power through which subjects are identified and so positioned in culture, and/or the glorious articulation of sexualized bodies across a range of femininities, bodies that in one way or another enunciate a kind of agency that allows them to speak against the grain of imperial, racist, classist, homophobic, and other forms of discrimination–all of which are inherently also sexist and anti-women. This work is almost always articulated explicitly across and through the body for, as Foucault notes, the body is the field through which power is simultaneously experienced, challenged, and given new forms.

I believe that the return of feminism in its market-driven forms in the twenty-first century should be addressed with suspicion and even critical hostility. However, what should be embraced, debated, and given as much cultural space as possible, is the history of feminism and the renewed parafeminist impulse to extend the most important impulses of the feminisms of the 1960s while rejecting the binarism and tendency towards universalism within these earlier feminisms. We must honor the achievements of our earlier feminisms even as we remake some of their most important strategies in ways that are effective to the new ways in which power functions today.

Amelia Jones is Professor and Pilkington Chair in Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Manchester. She has organized exhibitions on feminism and contemporary art, has co-edited the anthology Performing the Body/Performing the Text (1999), and edited the volumes Feminism and Visual Culture Reader (2003) and A Companion to Art Since 1945 (2006). Following on her Body Art/Performing the Subject (1998), Jones’s recent books include Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada (2004) and Self Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject (2007). Her current projects are a co-edited volume Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History and a book tentatively entitled Identity and the Visual.