Flip Schulke, Hurricane Carla in Texas, 1961

Beyond the aesthetic appeal, I find this image interesting because of it’s paradoxical quality. In some ways it is a calm image, with its steadfast concrete anchor on the left and the ridged verticals of the light post and stoplight. The storm itself appears only as a nebulous white fog. Yet chaos is also present in the mass of lumber sprawled across the road by the violence of the storm. This wreckage contains a dichotomy of its own. While visually a complex jumble, the heap of lumber also symbolizes the power of the hurricane to obliterate, level, simplify; the storm has separated a structure into the most basic elements of its construction. The hurricane has also reduced the only person in the scene to an elemental state of being. Standing alone amongst the vestiges of a civilization rendered irrelevant and impotent by the storm, he succumbs to the basic emotions of fear and despair.

Bartholomew Cooke, Photographer

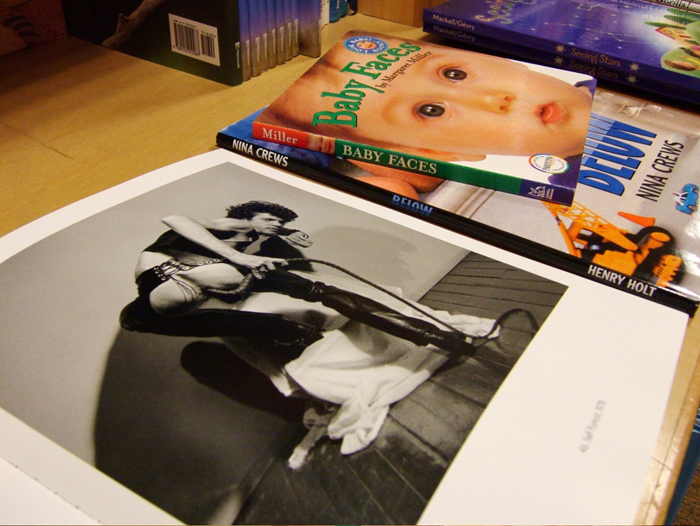

Jon Wasserman, Stop Looking at My Whip, 2006

When I was in high school, my girlfriend and I used to sit in the kids’ section at Border’s and look through the Robert Mapplethorpe books. When we were done, we’d leave the book open to a “mature” image. We felt parents had a responsibility to speak frankly with their children about uncomfortable subjects. I would commonly leave it open to the same page, my favorite of his pictures.

It’s the one of him standing in the studio, with a whip sticking out of his asshole. As an adult, I’ve read theory about cross-referencing codes and desublimation of the anus; but as a teenager, I was most captivated by his expression. The body says, “Come look at me, and absorb all this loaded content.” But the face has this complex look of annoyance at being disturbed, and confusion that you would be interrupting in the first place. It says both “go away” and “what do you want?” In thousands of pictures, I can’t think of any in which someone is looking so completely at you.

Jon Wasserman, Photographer

Louis Tremante, Tremante Family Photograph, ca 1969

This photo of my mother was taken in 1969 or 1970. When I was a kid, the photo was blown up and displayed over our upright piano. Becky, the Black Angus cow, is ramming my mother in the gut. My mother grew up on a farm, and she showed her prize cattle in state and local fairs. As a result, my siblings and I were appalled that her animal-handling experience could fail her in this moment. And why was my father behind a camera as it happened? My mom always said Becky was just playing, but this explanation seemed unlikely to me as child. When cows eat or want their necks scratched, they swing their big, bony heads up. If you stand too close, you will get whacked in the stomach or under the chin. Calves practice this when they nurse; first they switch their tails, then hit their mothers’ udders by jerking their heads. My mother’s story makes sense now, but it still does not erase the effects of years of speculation which fostered a secret pride in the implications of the image: my mom could take a hit, and she was tough.

Elizabeth Tremante, Artist