This text was commissioned by X-TRA as part of Field Perspectives 2017, a co-publishing initiative organized and supported by Common Field as a part of their Los Angeles 2017 Convening. Field Perspectives 2017 is a collaboration between Common Field and arts publications ARTS.BLACK, Art Practical, The Chart, Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles, contemptorary, DIRT, Pelican Bomb, Temporary Art Review, and X-TRA. Partners each commissioned a piece of writing that aims to catalyze discussion, dialog, and debate before, during and after the Convening. Published here on October 12, 2017.

“The truth is, polarization is exactly what we are trying to fight.”

–Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement1

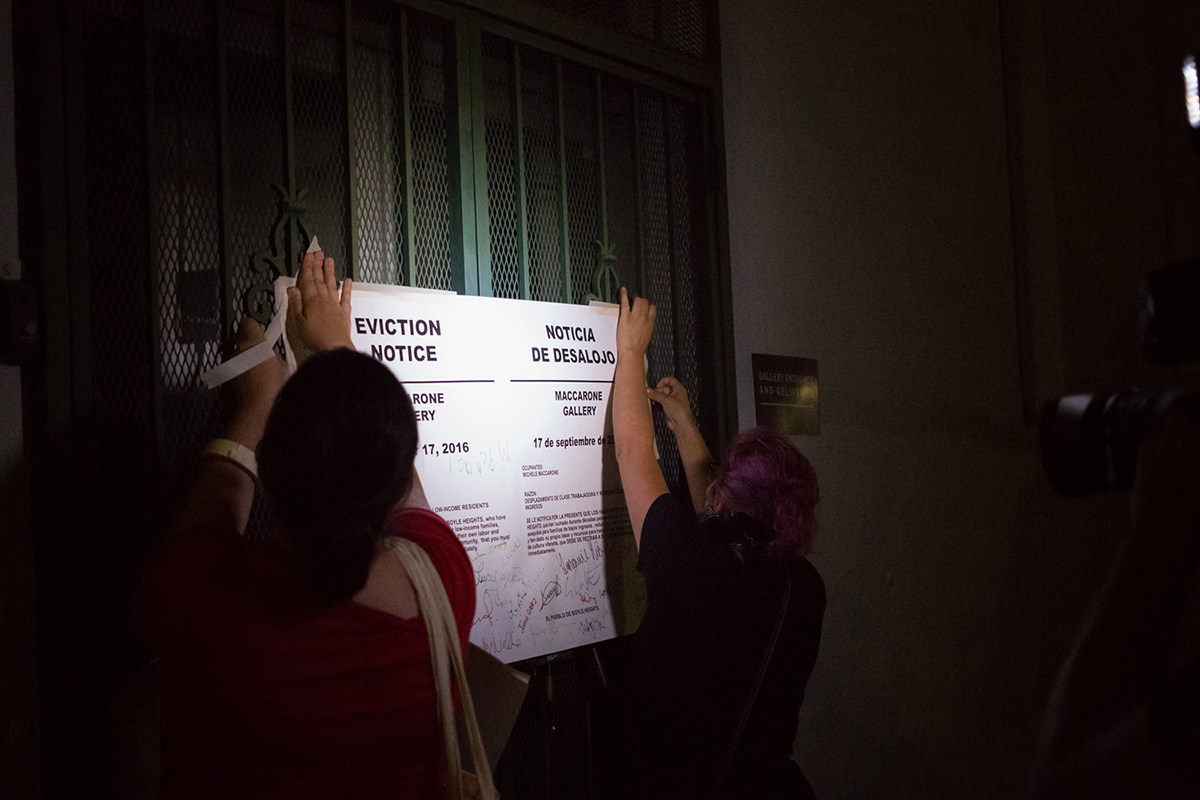

In September of 2016, a coalition of activist groups called the Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement (BHAAAD) marched to Arts District galleries on the east side of the river, down Mission Road, between 3rd and 4th Streets, and Anderson Street, between 6th and 7th, and served them with eviction notices. “You are hereby notified by the people of Boyle Heights, who have fought for decades to preserve affordable housing for low-income families,” the mock notices read, “that you must remove your business from the neighborhood immediately.” It was a small taste of what faces the galleries’ neighbors.

In a milieu that thinks of itself as politically progressive, and that claims to value nuanced, balanced discourse, the activists’ unqualified stance has art-worlders rattled. The founders of artist-run gallery PSSST were caught off guard when anti-gentrification groups protested their grand opening. In February 2017, Los Angeles-based filmmaker and artist Ambar Navarro cancelled a screening of her work at the 356 Mission gallery in solidarity with the boycott—while, in the Facebook post announcing her decision, Navarro urged people to look at both sides of the issue. Guadalupe Rosales grew up in Boyle Heights and makes work about Chicanx history; she also had her reservations, but chose to go through with a residency at PSSST.2 People throughout the art scene feel conflicted and angry. Many find the activists’ demands unreasonable or unrealistic. Some think maybe the galleries in Boyle Heights should just leave.

In contrast to the equivocation of much of the art world, BHAAAD has made a strategy of absolute certainty. While 356 Mission has remained open to dialogue, the activists demand nothing less than the keys to their building. In directing their complaint at every gallery in Boyle Heights, the activists lump together outfits from UTA Artist Space, a Hollywood talent agency’s art showroom, to Self-Help Graphics, an Eastside print shop and community center that has served the area since the 1970s, when it was founded during a previous burst of political organizing. This was also the period when what is now the world’s busiest freeway interchange carved up East Los Angeles; in the early 1960s, the south end of the 101 severed a few residential blocks from the rest of Boyle Heights, pinning those houses (including the Pico Gardens public housing project) in with the garment factories and beer distributors that abut the Los Angeles River at the neighborhood’s westernmost, industrial fringe.

The demand that all galleries leave the area is a demand that the citizens of Boyle Heights be allowed to determine the composition of their neighborhood. This absolutism has its mirror image in the discriminatory, racist policies of the Federal Housing Administration that, between 1934 and 1968, made it next to impossible for residents of certain areas to obtain loans. In a practice known as redlining, the Federal Housing Authority produced color-coded maps designating areas as desirable or, in their bare euphemism, “lacking homogeneity.”3

Protesters post eviction notices on the gates of Maccarone Gallery, September 17, 2016. Courtesy of Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement.

“Yellow areas are characterized by age, obsolescence, and change of style; expiring restrictions or lack of them; infiltration of a lower grade population; the presence of influences which increase sales resistance such as inadequate transportation, insufficient utilities, perhaps heavy tax burdens, poor maintenance of homes, etc. “Jerry” built areas are included, as well as neighborhoods lacking homogeneity. Generally, these areas have reached the transition period. Good mortgage lenders are more conservative in the Yellow areas and hold loan commitments under the lending ratio for the Green and Blue areas.

Red areas represent those neighborhoods in which the things that are now taking place in the Yellow neighborhoods have already happened. They are characterized by detrimental influences in a pronounced degree, undesirable population or infiltration of it. Low percentage of home ownership, very poor maintenance and often vandalism prevail. Unstable incomes of the people and difficult collections are usually prevalent. The areas are broader than the so-called slum districts. Some mortgage lenders may refuse to make loans in these neighborhoods and others will lend only on a conservative basis.”

In 1938, on one of the first redlining maps, Boyle heights ranked in the fourth grade: red. “This is a ‘melting pot’ area,” notes a pre-war government report, “and is literally honeycombed with diverse and subversive racial elements. It is seriously doubted whether there is a single block in the area which does not contain detrimental racial elements, and there are very few districts which are not hopelessly heterogeneous in type of improvement and quality of maintenance.”4 The suburbs of the mobile, white upper- and upper-middle classes continued their social convection, while poorer areas and ghettos, especially black and immigrant neighborhoods, were left to stultify. The people who were already there—“Jewish professional and business men, Mexican laborers, WPA workers, etc.,” as the report says of Boyle Heights—were effectively trapped.

The protesters’ ultimatums should be viewed within the context of this harsh history. A broadsheet published by the L.A. Tenants Union, members of BHAAAD, declares, “We must move beyond asking for crumbs and only making demands considered ‘realistic’ and ‘acceptable’ by the system that creates the housing crisis in the first place.” Where equivocation has failed, “We must start making demands that ask for what we really need.”5 But within BHAAAD, absolute certainty is more of a tactic than an ideal. “The only way you can start this conversation is by saying no,” activist and Boyle Heights resident Leonardo Vilchis told the Los Angeles Times. “The only way we are heard is when you say no. And that’s terrifying because you’re a jerk who says no. But we have had more negotiations now since we’ve said no than if we had said yes.”6

A member of Defend Boyle Heights holds a sign at Self-Help Graphics protesting against several art galleries that have opened recently in Boyle Heights, July 2, 2016. Courtesy of Los Angeles Times. Photo: Steve Saldivar.

Vilchis is also a member of the radical sound collective Ultra-red. Founded in 1994 by Los Angeles artists and activists Dont Rhine and Marco Larsen, the group has grown to include members in Canada and the United Kingdom. Their projects range from electronic albums and sound collage to public education and community organizing, which take the form of programs by the School of Echoes. Many of the group’s members are also founding members of the Union de Vecinos (Union of Neighbors) and the Los Angeles Tenants Union, both of which participate in BHAAAD but predate the present conflict. One of Ultra-red’s major works, the album Structural Adjustments (2000), incorporates field recordings that document a past struggle by the residents of the Pico Gardens housing project, who faced eviction in the mid-1990s when the Housing Authority tried to clear their buildings. The movement succeeded and the residents were not evicted.7 A fellow musician describes the group members as “True participants in social struggles, not ‘political art’ bullshitters.”8

In June 2016, Ultra-red posted an open letter to Hyperallergic, a New York-based art journalism website that has hosted the most thorough coverage of the Boyle Heights arts district controversy. The letter is one of the strongest declarations of support for the Boyle Heights activists by active art-world participants. This is not surprising, considering the group’s position at the intersection of activist, political, and artistic organizations. “Even before our collective formed in 1994,” they write, “members of Ultra-red stood with the residents of Pico Gardens in the 1980s, then through the founding of Union de Vecinos by thirty-six public housing families in 1996, and up to today.”9 Their letter marks a continuation, a through-line from the struggles to save Pico Gardens and public housing in Los Angeles to the current one. When Boyle Heights organized against the galleries it was partly because they had done it before; they could recognize the new face of an old struggle.

On a February morning in 2017, a group called the Artists Political Action Committee (APAN) arrived for a meeting at 356 Mission but found the entrance blocked by a handful of activists with a bullhorn. The solidarity art-worlders felt—or sought—after Trump’s election did not erase the hard line drawn by BHAAAD and its affiliates between those art venues gentrifying Boyle Heights, unwittingly or otherwise, and those fighting to preserve it in its present state. Artists who showed up for the APAN meeting had to choose between crossing the picket line or turning back. “You are on the wrong side of history,” yelled the protesters. They cast the word picket like a spell.

Scholar Nizan Shaked wrote about her experience that day: “Unless you strongly disagree with the position of the picketer,” she decided, “you just do not cross a picket line. That is activism 101.” 10 Shaked’s piece was titled “How to Draw a (Picket) Line,” and draw a line is a good term for what happened. Picketing as a tactic evolved out of organized labor—organized, in particular, around a class relationship between the workers and the owners. In calling their protest a picket, BHAAAD appealed to the morality of class fellows. Side with us, your fellow art-workers, they said. Our cause is just, and if you cross this line, you side with our exploiters and subjugators, the abstracters of our wealth. “Boycott 356 Mission,” sang the bullhorn. “Don’t cross the picket line. Boycott 356 Mission.” Protesters called, “Scab,” after those who went inside. “SCAB! SCAB!”11

BHAAAD protesters and APAN meeting attendees gather outside 356 S. Mission Rd, Los Angeles, February 12, 2017. Photo: Nizan Shaked.

But who is the owner here? The owner of the building, maybe.12 The owner of the gallery or the gallery’s fiscal backers. As art critic Ben Davis points out, artists have aspirations that bring them in contact with the ruling class, while their sympathies and their self-image align with the working class. But artists themselves are best understood as middle-class—small business owners, sole proprietors.13 Where artists are both complicit and concerned, the activists made their appeal.

Short of a true picket line, the protests outside 356 Mission were a rhetorical form. Specific arguments don’t serve. Instead, the idea of us/them must be drawn out to an extreme, abstracting the cause of anti-gentrification and the cause of labor rights until they match. Artists were the workers and artists were the owners, too. “356 Mission is a developer, just like Donald Trump,” the activists are fond of saying—drawing a gross equivalency between our grifter-in-chief and whatever abstract owner holds sway here, in Los Angeles, in Boyle Heights, on the 300 block of South Mission Road.

Like the picket line, this unequivocal stance recalls the heyday of organized labor more than it resembles the popular movements of the twenty-first century. Occupy Wall Street, for example, was defined by one feature in particular: Occupy made no demands. BHAAAD’s binary stance is specific to their experience fighting gentrification in East Los Angeles, where developers’ hard boundaries must be resisted with even harder rhetoric. Occupy had a different, more abstract target—the machinations of capital writ large—and learned a different lesson. Capital cannot abide a limit; it must turn it into a barrier, then transcend it.14 Both a banking regulation and a union demand make excellent limits.

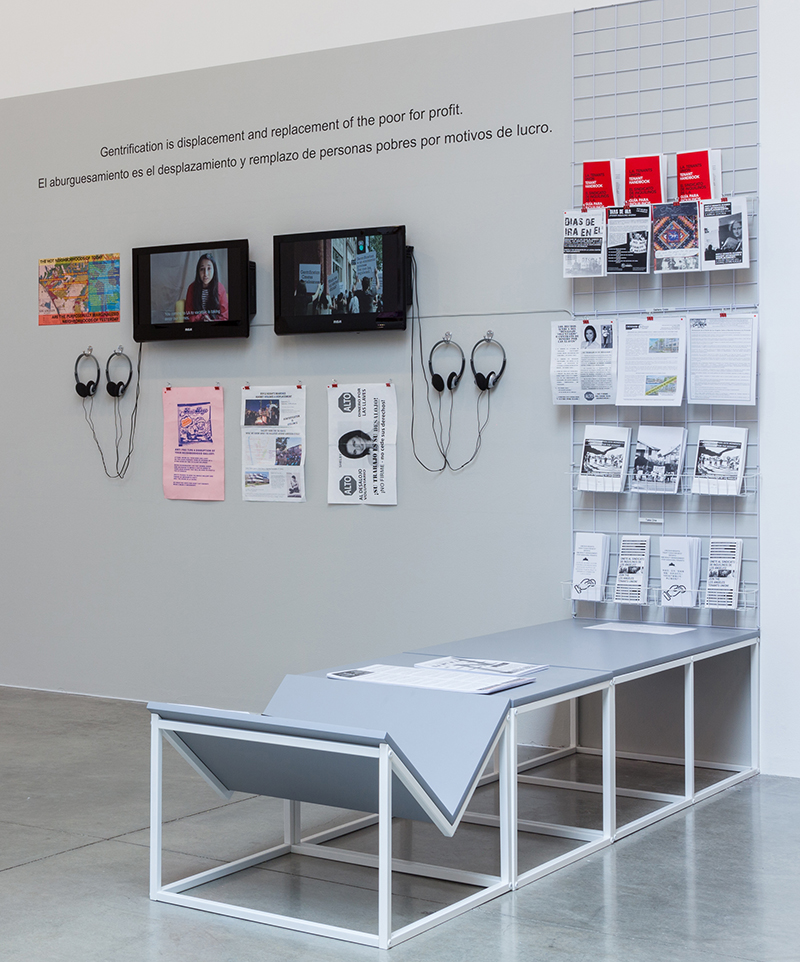

The galleries and artists, meanwhile, have been surprised to find themselves on the wrong side of the line. Artists and academics indeed pride themselves on identifying with underrepresented populations and repressed movements. Ultra-red is no exception. In an exhibition called Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas (affiliated with the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative, “LA/LA”), the collective presented their Los Angeles Library for Anti-Gentrification (2012–17).15 The installation includes a bench and wall-mounted rack stocked with pamphlets and one-sheets related to recent anti-gentrification struggles—particularly by the Los Angeles Tenants Union and the Union de Vecinos—and two monitors looping 13 videos documenting anti-gentrification actions and landlord shenanigans. The library positions the literature of the past five years of anti-gentrification activism squarely in an art context. Ultra-red has declared for Boyle Heights, but they continue to participate in the contemporary art system. In so doing, they render the short history of gentrification an object of mutual analysis for activists and artists alike—a common text. “In trying to establish a fine arts space within the professional sector,” Dont Rhine, a founding member of Ultra-red, told KCET, “it’s next to impossible to start or maintain that space without direct complicity in speculative development. It’s impossible to escape complicity.”16 Or—as Rhine phrased it in an earlier article, “How might our cultural actions refrain from the same mechanisms of domination from which we hope to produce emancipation?”17 This is a realistic picture. But is it enough for artists to be aware of the reality of their complicity?

Ultra-red, Los Angeles Library for Anti-Gentrification, 2012–2017. Printed booklets, posters, and videos. Installation view, Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas, Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, September 17 – December 10, 2017. Courtesy of Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design.

The picket line has sides—in and out, in front of and behind, picketer and scab. The picket line is the limit that gives traction to capital. We talk about “the right side of history,” as if history were a demarcation or a border. Rather, it is a timeline. There are crucial differences. A timeline has directionality, like a sound wave; it indicates, like an arrow. And it offers, simply, an escape from cyclical time—the time thrown out of joint by which the medieval became the modern and by which the same old struggle yields progress. Thus, it’s not only the shape of the line that describes the priorities of artists, but also the ways they spend their energy defining it, preserving it, and measuring distance from it. The form of the collage or collection, elastic and ultra-red, offers an alternative to the border. x

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He serves on the editorial board of X-TRA.

Read responses to this article from Ultra-red and Nizan Shaked.