William Pope.L, A Vessel in a Vessel in a Vessel and So On, 2007. Pirate lady statue; Martin Luther King, Jr. plaster bust; wood; pump; light; chocolate; 3 x 3 x 10 feet. Unique. Courtesy of the artist and MC. Photo: Joshua White.

A combination of sculpture, drawing, found objects, installation, performance, and hybrids of all of the above, William Pope.L’s work consistently plays on the contradictions, paradoxes, and absurdities of social roles and situations through the lens of a very serious sense of humor. Though called many names throughout his career, at the center of this varied practice is a concept of the void.

For Yves Klein, the void contained a Zen immateriality and airy neutrality. In Klein’s void, things were represented by their absence; his cool blue monochromatic paintings are almost serene, his books without words and his compositions without music are palliative paeans to nothingness. A work such as Leap into the Void (1960) shows a beatific artist swan-diving from a second story window, seconds before a face plant into the cement, the hint of a transcendent grin on his face, while in the distance a man on a bicycle passes by unaware. Or in any of the International Klein Blue monochromes and anthropometries, Klein saw these as pictorial representations of the void, finding support in the philosopher Gaston Bachelard: “First there is nothing, next there is a depth of nothingness, then a profundity of blue….”1

William Pope.L also defines the void by what is not there, but his lack is not neutral. His void exists in a place of extreme ambiguity and is far from serene, any number of the possible readings being radical, diverse, and politically charged, lambasting doctrinaire attitudes and playing many angles on sensitive issues.2 And though he inhabits Klein’s trickster spirit, Pope.L, the self-proclaimed “Friendliest Black Artist in America(c),” happily lacks the French artist’s airy philosophies. The void of Pope.L’s practice is neither a celebration of blackness nor an exhortation, but somehow both; it is the exploratory action of its own meaning, and no symbol–of the black community in particular–is sacred. For Pope.L, the void gives structure to imposed identity; we are what we do not have (have-nots if you will), or, as Pope.L states in an interview with Lowery Stokes Sims,”Blackness is a negotiation, not a necessity.”3 Reducing Pope.L’s oeuvre to the simple economics of haves and have-nots is criminally reductive; race is always at play.

According to the gallery, MC set the stage for “The Void Show” with Pope.L’s The Shed Piece (2006) at the Frieze Art Fair in London. In this installation, a long pipe coming out of the wall splurted and globbed a steady stream of peanut butter (a ton of it, if the press release is to be believed), onto a fluorescent blue garden shed. The interior of the shed was filled with garden tools, all painted blue, and a single channel projection that showed people in white suits crawling through gardens, unearthing bulky blue landmines. Peanut butter, the quintessentially American food invented by a black man, George Washington Carver, plays a role in much of Pope.L’s work.4 But two thousand pounds of oozing peanut butter produces a disgusting, disturbing, theatrical sensuality that’s hard to forget; constantly in motion, performing for the audience.

Pope.L reproduces this theatrical mode in “The Void Show,” which is composed of four pieces: two small drawings and two large sculptures. Stage lights bolted to the walls create the dramatic feeling, their long black cords snaking across the ground and up to plugs in the ceilings high overhead. The lights give each work a hard shadow, and produce a silhouette of the viewer that becomes part of the piece.

Walking into the darkened gallery from the entrance, one is greeted by a robust plaster statue of a “pirate wench.” Cartoonishly exaggerated, her scantily clad body is bountiful in the ways that entice buyers of pornographic magazines. Wearing gold buckled boots, a privateer’s frock coat, and a knotted shirt barely concealing her form, she holds a mirrored platter in one hand (the other hand replaced with the predictable hook). Lest I forget to mention, the pirate wench is hanging upside down from the ceiling, her wooden stand bolted to a large black box, which is rigged to the ceiling beams. To add another indispensable detail, the pirate wench has been decapitated; remnants of her long root beer brown hair remain on her shoulders, but her head has been replaced by a golden bust of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. An incandescent light glows within the body of the wench, creating a ghostly effect through the paint on the plaster. King’s eyes have been removed, and his hollow stare meeting the viewer at eye level is disconcerting. Furthermore, the crown of King’s head drips gooey chocolate syrup from a long thin cord that runs through the wench’s body. The dripping chocolate creates an ever-expanding puddle on the cement floor. This upended chimerical monument, titled In a Vessel in a Vessel in a Vessel and So On (2007), is hollow from the pirate’s booted toe to King’s crown. The dripping goop gives an illusion of substance, but the statue maintains its emptiness.

Returning to the gallery over a period of weeks, I witnessed the chocolate puddle grow bigger, demanding more attention. The sweet stench, and slick, sticky pool reflecting the theatrical lights is ominous, like a sci-fi blob obliterating all that comes in its path.

King, arguably at this moment the most famous and revered black man in American history, has made many appearances in Pope.L’s work; his face was grafted onto bags of manure (Rebuilding the Monument, (1995-99) and his DNA was injected into fruit (distibutingmartin, 2001 -). A man given the honor of his own personal holiday (while all the other black Americans get relegated to the month of February), King becomes, in his civic sainthood, a site for Pope.L to challenge prescribed meaning.

Pope.L’s play with blackness hasn’t always been appreciated by the black community. During the “eRacism” exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, I saw video documentation of his Tompkins Square Crawl (1991), in which Pope.L, crawled through the gutter in a business suit, pushing a potted flower in one hand while a videographer documented the performance. During the performance, a black man from the neighborhood approached Pope.L, asked if he was okay, and then turned angrily at the unseen but obviously white cameraman to ask him what the meaning was of his filming a black guy crawling in the gutter. The interchange between Pope.L, the angry black bystander, and the cameraman became increasingly heated, despite Pope.L’s attempts at peaceful resolution. The man exclaimed, “I wear a suit like that to work!” and “You make me look like a jerk!” Though stopped after less than a block, the piece was wholly successful in illustrating racial tension. Pope.L, as a black man in an abject situation, became for the angry bystander a symbol of black people everywhere. The yellow flower in the small pot clutched in Pope.L’s hand became a point of comic absurdity in a painful interchange during a degrading ceremony, a mixture of the comic and the abject also found in The Void Show.

On the two walls of the gallery, on either side of the pirate wench statue, are drawings by Pope.L, photocopied and mounted on wood. Like a silly, puerile version of Artaud, the drawings are, like the pirate wench, both cartoony and totally fucked up, almost schizophrenic in their energy as they depict penises erupting from the feet of big-nosed men lying in state. The tears of one giant’s disembodied head seem to slime out of its heavily mascaraed eyes. Scrawling, illegible handwriting circles crude desert landscapes and mutilated bodies. The rough drawings are grossly sensual in their comic degradation. These kinds of drawings are curious additions that I’d not seen before from Pope.L, but in their mad energy, absurdity, and curious construction they all bear the distinctive marks of the artist.

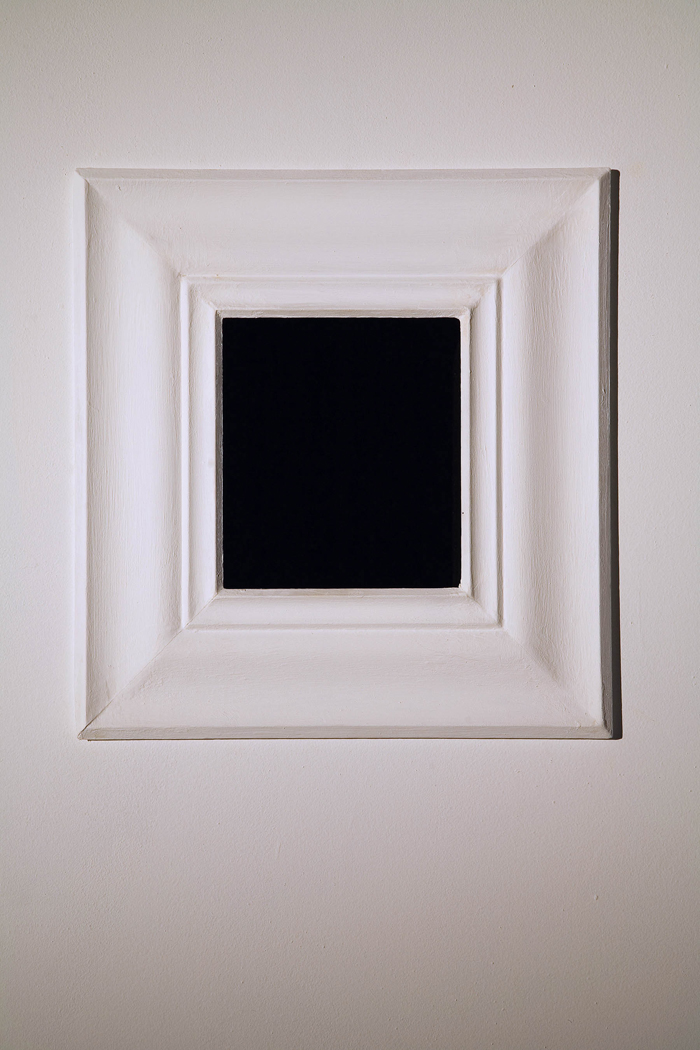

William Pope.L, The Void Piece, 2007. Room, wall, black hole; Dimensions variable. Edition of 3. Courtesy of the artist and MC. Photo: Joshua White.

William Pope.L, The Void Piece, (detail) 2007. Room, wall, black hole; Dimensions variable. Edition of 3. Courtesy of the artist and MC. Photo: Joshua White.

In the back of the L-shaped gallery, one finds the central work of the exhibition, The Void Piece (2007). A nine foot high wall cordons off a large section of the gallery. Set into the wall, in a white frame, is a black hole from which blows a light, steady air stream. A small white wooden box on the floor, now covered in visitors’ footprints, forms an invitation to step up and look into the hole, into the dense blackness. I was tempted, as I’m sure everybody is, to stick my arm into the hole, though some human survival instinct prevented me from doing so.

Pope.L, has stated, “Have-not-ness permeates everything I do.”5Thus the lack, the Void, or the Hole, as he has often called it, becomes not only a place to fill with readings, it also takes on tones of Marxist critique. Pope.L is not likely to be tightly ideologically aligned with the dead German communist–like all wise tricksters he’s surely not aligned with any ideology–but the central lack is both one of race and subsequently meaning, as it is of money within a capitalist class system.

Pope.L wrote about the nature of holes in “Hole Theory: Parts Four and Five.”6 His tract reads like a poem, an extended sermon, a polemic, and a manifesto. All these words are malleable. (Pope.L articulates Hole Theory about as clearly as Frank O’Hara does “Personism.”) But even though Pope.L ducks and moves with evasive, poetic precision (more like Jules Renard’s “deliberate vagueness”7 than the Communist Manifesto’s proletarian clarity), he says a few things that might prove useful:

When I imagine a hole

That is only this or only that

I am not after purity […]

But hilarity.Holes are not the point.

Holes are empty theory.When I say–

Hole theory explains nothing

This is only in order to create

A platform from which to engage everything.

Though a void may be read very literally as a hole in wall, The Void Piece creates a place of nothing from which to “engage everything,” another place to impose our meanings, whatever they may be. Unlike the pirate wench, besides the heavy-handed symbolism of a black hole in a white wall there appears no other referentiality, and because of this, The Void Piece is Pope.L’s most mature work to date. It says everything that needs to be said without the wisecracking pranksterism, opening up the conversation immensely. In most of the literature surrounding Pope.L, critics have dubbed his signature piece to be the aforementioned performance series Crawl, where in various costumes, from business suits to a Superman outfit, he crawls though cities from Tokyo to New York pushing or carrying various objects, from small potted flowers to a skateboards, with laborious care. But even more than Crawl, The Void Piece emerges as central to the realization of his practice.

A stage light points at the framed hole, but one lone incandescent light bulb hangs over The Void Piece, shedding light on the subject that can’t be seen. The prankster in me immediately wants to believe there might be something fantastical back there: buckets of chocolate, or an apartment for Anthony Burdin, or a hundred thousand rubber ducks, fifty mannequins in Superman costumes, Pope.L’s collection of potted cacti… (Actually, Pope.L did joke that he had finally found a way to imprison God and he’s farting on our faces from within.) All this play, though seemingly invited, seems ultimately to infer that behind the illuminated frame of the void, there is just more void: a space defined by absence.

I couldn’t help to ask the consuming question of Associate Director of MC, Harry McGowan. A slight plea in my voice, I asked, “So what’s on the other side of the wall?” And he riposted with the only appropriate answer, “The Void.”

Andrew Berardini is an assistant editor at Semiotext(e) Press and a writer living in Los Angeles. This is his second review for X-TRA.