Virginia Dwan, 1969. Dwan Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Of the forty-one commercial galleries listed in the greater Los Angeles Yellow Pages in 1960, only Ferus Gallery could rival Virginia Dwan. Both outfits were intent on making an impact in the city, both gravitated toward difficult artists, both harbored ambitions beyond the Los Angeles marketplace, and both debuted significant New York-based artists. Yet Dwan and Ferus differed in significant details: Virginia Dwan would make a name for herself by exhibiting the French Nouveaux Realistes while Ferus rarely crossed an ocean to find new work; Dwan benefited from significant cash resources, Ferus had little; Virginia Dwan despised the business of art and left deals to her staff, Ferus director Irving Blum relished the sale; Dwan placed a few artworks at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, while Ferus enjoyed strong connections to the Pasadena Art Museum.

In the end, though, their similarities outweighed their differences. Both pushed an agenda of contemporary art in a city that barely accepted Duchamp. Both scraped together collectors when their likes were scarce, and both galleries were run by passionate personalities.

Yet the Ferus legend mushroomed even as Dwan’s Los Angeles years remain, to this day, obscure. How come? Why has Dwan gone largely uncredited in the development of postwar Los Angeles art?

Though Dwan made a career as an art dealer, her style was closer to that of a high level patron. As a young patron, Dwan gravitated toward California artists such as Sam Amato and the University of California Los Angeles educated James McGarrell, as well as European masters. A small Pablo Picasso etching and an Honore Daumier drawing were also among her early purchases.1 As the daughter of John C. Dwan, co-founder of Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Company, later 3M, she was heir to her father’s fortune, set at $22,579,000 in 1961.2 As Dwan explains it: “As much as I don’t like to think of it as a money issue, I have to acknowledge the fact that I had a private income myself which made it possible for me to take a more idealistic stand, or devote myself more to the artist than perhaps a lot of other dealers would do,” she said. “I knew I was going to be able to keep the doors open.”3

Dwan set up shop far from the burgeoning La Cienega art scene, in a modest storefront space at 1091 Broxton Avenue, a move that indicated a lack of experience. Tucked in a commercial strip in the Westwood neighborhood near UCLA (where her husband studied medicine) and some miles from downtown, her gallery struggled to lure crowds. She had naively thought that visitors would seek her out but soon found that she could not compete with the La Cienega gallery district and its Monday night art walks. However, she learned quickly. As Dwan recalls it, the Broxton space was narrow, “maybe about 50 feet deep and 22 or 23 feet wide…. It wasn’t an ideal space to show in.”4 The walls could accommodate works as large as Rauschenberg’s eight and a half foot tall Rigger, but just barely. She would move to a custom-designed gallery on Lindbrook in the spring of 1962.

Her first year exhibition roster was largely given over to New York artists on consignment from East Coast galleries. Works borrowed from Manhattan galleries Peridot, Leo Castelli, and Tibor de Nagy helped Dwan showcase adequate if uninventive iterations of Abstract Expressionism. Though these shows did not indicate significant innovation on Dwan’s part, they were the artworks most likely to please her West Coast audience.

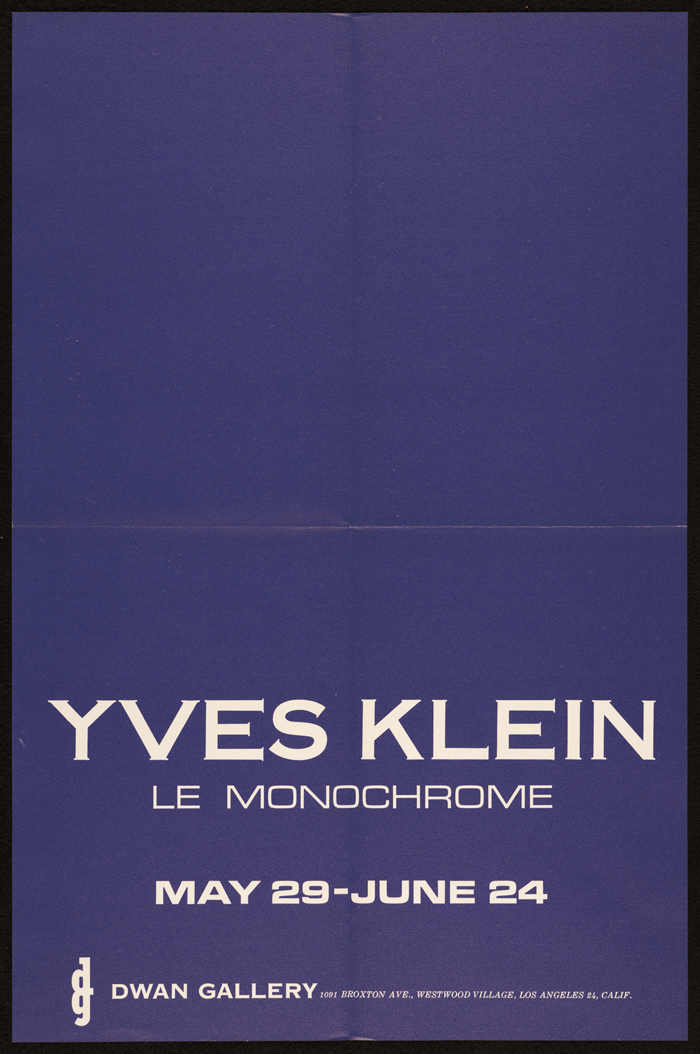

Dwan began to flex her muscle after meeting Yves Klein in early 1961. From then on, she developed her own curatorial vision, alienating the critics of Los Angeles in the process. She began to choose artists that rejected or questioned Expressionist tendencies, some to such a degree that their status as artists was questioned. Klein was one of them, of course; he made his Los Angeles debut in May of 1961, just a month after his first American solo show opened at Leo Castelli in New York. His exhibition at Dwan, called Le Monochrome, opened May 29 and marked Dwan’s first show of an artist untested by the New York market and untouched by the East Coast imprimatur.5 It featured pink sponge paintings, drag paintings, monochromes, sculptures and “wonderful objects called obelisks in blue, red and gold leaf.”6 She also showed some of Klein’s very first fire paintings.

It was a show that left critics literally speechless–there were no reviews. Dwan remembers local artists complaining bitterly that a foreigner was taking up valuable wall space. Yet Dwan’s association with Klein inaugurated an important allegiance with the French postwar avant-garde. Dwan championed the Nouveaux Realistes, which included Klein, Martial Raysse, Arman, Niki de St. Phalle and Jean Tinguely. She was the first Los Angeles gallery to show Klein, Raysse, and Arman, and would later host performances and exhibitions by de St. Phalle and Tinguely. Such connections were unusual in Los Angeles at the time; young artists who visited Dwan’s gallery, such as the painter John Baldessari, were moved and influenced by what they saw on her walls. Baldessari recalls seeing the Klein monochromes on Broxton Avenue in 1961 and the indelible impression those works made. “It just defied everything I knew about art,” the artist recalled.7 But Dwan’s allegiance to European artists like Klein would prove a handicap for her. Because of Los Angeles’s embrace of Cold War anti-European sentiment, even acknowledged greats of Nineteenth Century French art were suspect. Surrealism and Dada got little to no attention in the city.8

Dwan’s other strong attachment was to the burgeoning neo-Dada movement in America, in particular to the artists Edward Kienholz and Robert Rauschenberg. In many regards, Kienholz and Rauschenberg represented an American strain of the French Nouveaux Realistes, as both groups used everyday objects as the basis of their work and moved away from the predominant abstract painting practices of the time. Dwan had shown both Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg in group shows with her New York School artists. But in the final months occupying her Broxton Avenue gallery, Dwan made a stronger statement in favor of New York neo-Dada by hosting Rauschenberg’s first West Coast solo exhibition in March of 1962. On view at Rauschenberg’s Dwan show were ten combines plus some of the artist’s drawings on consignment from Castelli. Included in the show was First Landing Jump (1961), now at the Museum of Modern Art, and Blue Eagle (1961), now owned by New York’s Whitney Museum. The show garnered no reviews in the local papers and predictably, perhaps, collectors balked even after Dwan devoted a full year and half to the sale of Rauschenberg’s combine First Landing Jump,. As she recalled later, one person considered it, then another, and yet another collector, in Texas. Finally, with no takers in sight, she crated the work for its trip back east.9

By far Dwan’s most intense creative allegiance was with Kienholz. Reflecting both Dwan’s stature as a dealer and her sensitivity to her artists, Kienholz defected to her gallery in 1963 after six years of cofounding and showing at Ferus. Kienholz stated that he wasn’t comfortable with the “fuck you” Ferus attitude and expressed disappointment with his erstwhile friend Billy Al Bengston’s embrace of macho motorcycle culture.10 Under Dwan’s auspices, Kienholz’s tableaux works flourished and he debuted some of his most important art with her. Years later, John Coplans acknowledged, “I don’t think that he [Kienholz] would have managed quite as well without her patronage.”11 On view in Kienholz’s first Dwan exhibition, in June 1963, was his grim takeon abortion, The Illegal Operation, later viewed as one of his most important works. And, as Anne Ayres has written, Kienholz’s major artistic move into three dimensional, object-based tableaux likely evolved out of his friendships with Tinguely, Arman, and Klein.12 All of those friendships were brokered by Dwan.

If Keinholz and Rauschenberg recognized Dwan’s sharp taste and curatorial leadership, if they found creative riches in their friendships with her “exotic” European artists, and if young Baldessari–and countless others–educated his eye in her gallery, it seems hardly possible that Dwan remains outside the history books. Yet there was Ferus to contend with, and likewise fixed notions of what constituted the avant-garde.

Southern California’s expanding group of assemblage artists would find voice and exhibition space at both Ferus and Dwan, yet Blum and Dwan diverged in their treatment of local artists. Blum became well known for showing local artists whose work was influenced by Southern California culture. The slick, aggressive paintings of Bengston, who around 1960 began developing a personal symbology based on motorcycle emblems, would come to represent the Ferus ideal. Ed Ruscha was incorporating gas stations and tires into his work. Around the same time, Craig Kauffman departed from his spontaneous, painterly surfaces toward more polished paintings made on Plexiglas. Ken Price, the ceramicist, was also experimenting with sleeker forms. As Cecile Whiting has pointed out, Ferus was a macho place. The young men–and it was mostly men–who showed at the gallery drank, bedded actresses and models, and lived a Southern California cliche. Whiting put it this way: “Ferus Gallery portrayed a new type of creator: young, handsome, heterosexual, and inspired by a hedonistic California lifestyle.”13 Such an embrace of Hollywood stereotypes was uncharacteristic until Ferus artists tapped into it–until then, machismo had remained largely an East Coast affair linked with the New York School.

Announcement for Yves Klein’s Los Angeles debut at Dwan Gallery, 1961. Dwan Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Even Ferus’s exhibition advertisements in magazines like Artforum emphasized the artists’ virility–one example finds a sleeping Ruscha in bed with two women.14 From the looks of their publicity, at least, not only were these young men not ashamed of their city’s superficiality, they milked it. The work they created may have defied norms, but their means of getting attention held fast to mainstream gender stereotypes.

Some of that attention came from the press. Though there was some art writing at the time–the occasional “Art News from LA” feature written by Jules Langsner in ArtNews and Gerald Nordland’s reviews in the small circulation Frontier magazine–it was the establishment of Artforum that gave more publicity to both Dwan and Ferus. Founded in San Francisco in 1962, the magazine had a regular Los Angeles correspondent in John Coplans. From Coplans both Dwan and Ferus would get regular reviews. Ferus would enjoy an especially close relationship to Artforum, a relationship that may explain why that gallery got so much more attention than Dwan. As Ferus director Blum recalls, Artforum was “sympathetic to a great deal of…the activity around the Ferus Gallery, was enormously important and gave me a real leg up.”15 Indeed, when the magazine moved to Los Angeles in 1965, it moved into the same building as Ferus. Blum would recall that, “with Phil Leider at the head, who was also a great personal friend of mine–it was much more than useful.”16 That Blum cites Artforum as “useful” shows how he viewed its writers as public relations agents–their reviews weren’t so much critical as explanatory, explaining the art on view as if vouching for its importance rather than challenging it. Indeed, the magazine’s early aim was advocacy; its writers wished to pump up the Los Angeles scene. Artforum critics found themselves in a bind as they advocated for the significance of the Los Angeles art scene in the 1950s and 1960s: theirs wasn’t a dialog about art so much as a press release for it. Indeed, Artforum writer Coplans seconded that notion, stating that when his early advocacy of Los Angeles artists turned more substantial and more adversarial, Los Angeles artists balked.17

Yet life at Ferus wasn’t without stress. Despite the support of Sadye Moss, the gallery’s well-heeled silent partner, money was tight. Recalls Blum: “I would sell maybe one or two things; three things at the outside, which hardly paid for [anything] when you consider the little salary I was taking, the little salary Walter was taking, the gallery expenses, et cetera. We operated… in the red year after year after year.”18 By comparison, Dwan had money and Blum knew it. “Virginia Dwan for a time had fabulous exhibitions,” Blum recalls. “Poured a fortune into the gallery…. [And] had a fortune to pour in.”19 Indeed, Dwan’s largesse would become a staple of her dealing, allowing her to fly in European and New York artists and put them up at her home. It also allowed Dwan to make gorgeous exhibition announcements and catalogs. And, most importantly, Dwan’s money allowed her to stay in business. As for most of the rest of the galleries, Blum recalls them coming and going every two to three years.20

Edward Kienholz, The Illegal Operation, 1962. Mixed media/assemblage/collage: powered device, polyester resin, pigment, shopping cart, wooden stool, concrete, lamp, fabric, basin, metal pots, blanket, hooked rug, and medical equipment; 59 x 48 x 54 ins. Partial gift of Betty and Monte Factor and purchased with funds provided by the Art Museum Council, Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, the Modern and Contemporary Art Council, Dallas Price-Van Breda and Bob Van Breda, the Robert H. Halff Fund, David G. Booth and Suzanne Deal Booth, Virginia Dwan, Elaine and Bram Goldsmith, the Grinstein Family, Ric and Suzanne Kayne, Alice and Hahum Lainer, Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Mrs. Harry Lenart, the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Philippa Calnan and Laura Lee Woods (M.2008.107a-D) Modern Art Department, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In the early 1960s, collectors and artists were few and far between, so competition between Dwan and Ferus was serious. Though Dwan spoke of her visits with Blum as commiseration sessions where the two complained about the paltry Los Angeles scene, Blum describes a more competitive relationship. “It was very scary, because [Dwan] somehow was interested in a lot of the same people I was interested in,” the art dealer recalled. Blum remembered her arrival on the scene with anxiety. “I had my entre to Lichtenstein, showing Roy early on, and I had my access to his work. Now, here comes this new lady with quite a lot of money and a very lavish, big, new situation [her second gallery, on Lindbrook]. And I felt very threatened by her situation.”21

Dwan represented competition for business and for the collectors that Blum and Hopps had groomed though a collector education program that they had established.

Hopps’s move in 1962 to take a full-time curatorship at the Pasadena Art Museum helped Ferus gain connections in the museum world. The move was a significant boost for the Ferus artists, as Hopps would have the ear of some of the most important art world figures from then on.22 And when it came to that pivotal year, 1962–the year Pop art really broke in Los Angeles–all the connections and press that Ferus secured would ensure the gallery’s triumph in the history books while relegating Dwan to the shadows.

The Ferus Gang (Group Portrait of Artists from the Ferus Gallery), 1962. Clockwise from the upper left: Billy Al Bengston, Allen Lynch, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, John Altoon, Ed Kienholz, Ed Moses (center). Photo by Patricia Faure.

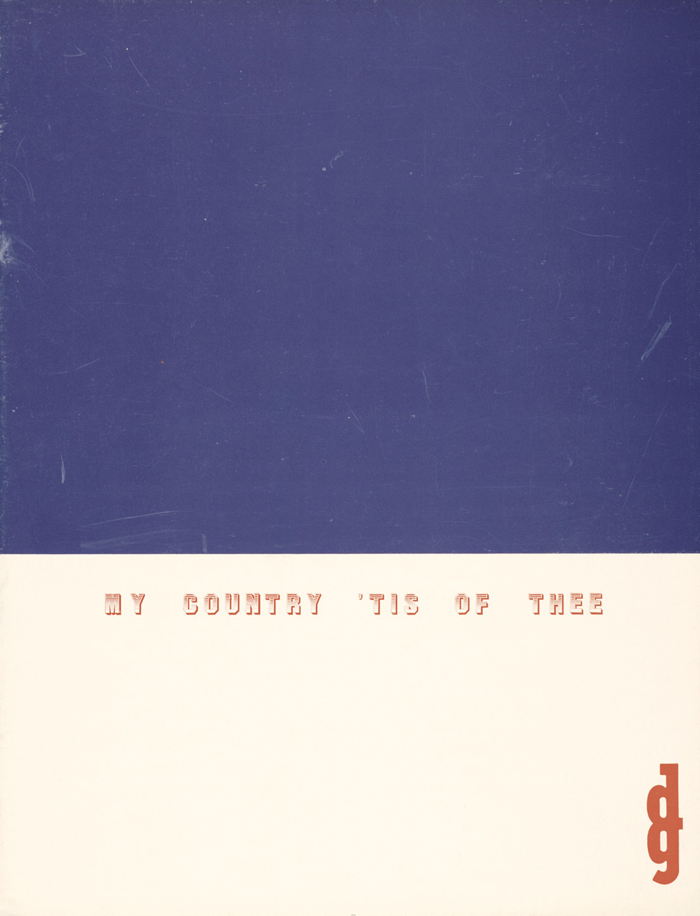

The second half of 1962 was the moment for Los Angeles Pop. July would see Andy Warhol’s first-ever solo show open at Ferus; in September, Hopps’s first major show, The New Painting of Common Objects, now widely recognized as the first exhibition of American Pop, opened at Pasadena. November brought Dwan’s My Country ‘Tis of Thee. Through the course of studio visits with Warhol, Wesselman, Oldenburg, and Rivers, Dwan noted artists using what she called “taboo” popular American imagery, images “which had been considered…declasse and…not intellectual before…. Suddenly, there’s this embracing of the very things which one was supposed to consider beneath them.”23 She combined this new work with the work that preceded it, such as Johns’s 1957 Flag on Orange Field. The resulting show, which filled her gallery with gaudy-colored sculpture and painting, had a kitsch and distinctly American sensibility. Marisol’s wood and mixed media sculpture group, The Kennedys (1962), greeted visitors entering the exhibition room. Behind it, on a low pedestal, stood John Chamberlain’s crushed steel Rayvredd, an early car work from 1962. One of Tom Wesselman’s Great American Nudes (1961) hung in a far alcove. That painting’s palette complemented Kienholz’s red, white, and blue mixed media Untitled American President (1962) and Lichtenstein’s war comic-based painting Takka Takka (1962). The exhibition palette and themes suggested patriotism’s intersection with consumption.

The overlap between Hopps’s and Dwan’s exhibitions is undeniable. Many of the same artists were on view. At the Pasadena Art Museum, Lichtenstein was represented by the canvas Roto Broil (1961), a cartoon-style depiction of chickens roasting in a home broiler. Ruscha showed Actual Size (1962), featuring the word “Spam” in large letters across its top half. Philip Hefferton showed the canvas Twenty (1962) depicting a twenty dollar bill. Andy Warhol showed a painting called S&H Green Stamps (1962), evoking the chits familiar to American grocery shoppers. All these paintings depicted objects typically associated with Americanism and American consumerism. In Dwan’s exhibition, Robert Indiana’s canvas featuring the insignia of the American Reaping Company and Oldenberg’s plaster diner coffee cup both conjured American corporate strength and easy access to resources. With her inclusion of Oldenburg’s Floorburger (1962), a work associated with the American penchant for fast, cheap food, Dwan certainly comes close to Hopps’s consumerist bent. Yet Dwan’s choices differed from Hopps’s too, including as she did the political aspects of Pop and popular culture with Marisol’s The Kennedys and Kienholz’s Untitled American President. Together Dwan and Hopps covered two sides of emergent American Pop–the political and the commercial.

Yet in the short catalog accompanying the exhibition, Dwan Gallery’s stance was admittedly less radical than Hopps’s. In an essay for the catalog, Gerald Nordland advocated for Pop’s inclusion in a high-art hierarchy, writing that this new work was part of a movement that would follow “Rothko, de Kooning and Motherwell.”24 Nordland both defended and made excuses for the new art, which he insisted did not elevate the common object, but instead: “These subjects are turned to not for the purpose of honoring them but in order to illustrate that anything can provide legitimate subject matter for the creative genius of the painter and sculptor.”25 Nordland’s comment about the “genius” of the artist ran contrary to the objectives of artists such as Oldenburg, who wanted to erase all trace of his so-called genius and of the artist’s hand.

At the very least, Dwan’s publication of Nordland’s essay argues for an understanding of Pop within the historical continuity of the avant garde, while Hopps positioned his exhibition as a radical break with Expressionism’s emphasis on artistic genius. Such a distinction is no small matter as it may offer a crucial clue to why Dwan’s reputation foundered. Though the historical record has been revised in recent years, the narrative of Pop that formed in the 1970s and 1980s stressed Hopps’s view of things, not Dwan’s.

Cover of exhibition catalog, My Country ‘Tis of Thee, 1962. Dwan Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Installation view of My Country ’Tis of Thee at Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles, 1962. Dwan Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Despite what may be considered Dwan’s flawed positioning of the nascent Pop work, it remains unclear why her exhibition has received so little attention. Dwan is barely recognized for her contribution to Los Angeles art history. Even the earliest chronicle of the Los Angeles art scene in the 1960s and early 1970s–Peter Plagens’s Sunshine Muse–contains errors, misattributions, and startling omissions. Plagens mentions Warhol’s debut at Ferus and Walter Hopps’s The New Painting of Common Objects as the two seminal Pop shows of 1962. He incorrectly cites My Country ‘Tis of Thee as opening the following year.26 For Plagens,

The seminal gallery was Ferus, opened in 1957–58 by Edward Kienholz, who supplied the moxie from his experience with earlier enterprises (Now and Exodus galleries, and Syndell Studios); Walter Hopps, a brilliant young Stanford art historian, who contributed the theoretical guidance and “eye”; and Irving Blum, a former Knoll salesman, who furnished the day-to-day management and front office suave.27

If we suspect that Plagens may have enjoyed associating himself with Ferus’s macho culture (and we do), we can’t ignore the fact that women authors miscast Dwan, too. Even the most recent book on the subject, Alexandra Schwartz’s Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles, barely mentions Dwan and ignores My Country ‘Tis of Thee altogether. Not surprisingly, Schwartz’s article in the Winter 2005 issue of October didn’t do any better.28

Between Plagens and Schwartz lie other omissions, notably by Maurice Tuchman and Anne Ayres in their essays for Art in Los Angeles: Seventeen Artists in the Sixties, a 1981 Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition. Both writers largely ignored Dwan and give credit to Ferus for defining the Los Angeles scene. Instances such as these are just the beginning.29

Of course, Dwan’s contributions have not gone completely unrecognized. Thomas Crow acknowledged Dwan, albeit in a backhanded way, in a 2002 article in Artforum, but he relegated her to second class after Ferus’s top billing.30 Nancy Marmer credits Dwan with greater influence in the essay “Los Angeles Pop” published in the Lucy Lippard-edited Pop Art in 1966; she gave Dwan equal stature with Ferus in the events of 1962. Yet it was Dwan’s support of the Nouveaux Realistes movement that is most often cited as her most significant contribution.

In the catalog of the Newport Beach Art Museum exhibition Los Angeles Pop in the Sixties (1989), Anne Ayres noted Dwan and her connection to the Nouveaux Realistes. Ayres stressed the connection between European Pop and neo-Dada to both assemblage and Pop art in America. In effect, she acknowledged that the introduction of Nouveau Realisme to Los Angeles changed the way that Los Angeles artists approached art making. More recently, Cecile Whiting, in her introduction to the 2006 Pop L.A.: Art and the City in the 1960s, seconded Ayres’s assertion. Whiting cited Dwan’s importation of the Nouveaux Realistes as significant because those artists’ use of mass-produced objects offered Los Angeles artists new strategies. Said Whiting:

A number of Nouveaux Realistes, including Arman, Martial Raysse, and Niki de St. Phalle, also visited Los Angeles in the early 1960s when the Dwan gallery mounted exhibitions of their art. With the arrival of Duchamp and the Nouveaux Realistes, a number of local artists, who shared the French engagement with the mass-produced commercial object, developed a connection to Europe no longer based on an expressionist adaptation of the grand tradition of modernism.31

It’s clear that Dwan-brokered relationships between the French neo-Dada and proto-Pop Nouveaux Realistes and the artists of Los Angeles yielded new modes of creating: tired iterations of Abstract Expressionism gave way to neo-Dada assemblage by artists such as Kienholz. Yet even Whiting couldn’t help devoting a chapter to Ferus’s macho culture of studs.

Dwan was as attuned to the American and European avant garde as her rivals. She went to great expense to showcase her observations on a new generation of artists. Yet her work was overshadowed by Ferus. Certainly Ferus’s media, museum and collector attention helped account for this. And, of course, Dwan was a woman operating her own business in late 1950s Los Angeles, a town still steeped in postwar conservatism. (And she chose to open the gallery in Westwood, not La Cienega.) Why wouldn’t the (mostly male) art critics gravitate toward Ferus’s stud culture and eschew “this new lady,” as Blum put it? Why wouldn’t the Los Angeles art world be put off by a powerful woman’s wealth? And should it come as a surprise that a xenophobic public shunned her for her European ties?

Yet given the reception of My Country ‘Tis of Thee–both at the time and in the decades to follow–perhaps it was that seminal year 1962 that really did Dwan in. For years after its emergence, Pop was read as a reaction against American Post-World War II riches and a deflation of Ab-Ex hubris, not a stage in an art historical continuum. Dwan’s vision of Pop didn’t resonate with 1960s and 1970s era radicalism and an intellectual culture that questioned dominant narratives. It’s true that Dwan found an opening in Los Angeles and was taken seriously in her time. But history wasn’t quite as kind.

Jessica Dawson is Director of Identity for the Hirshhorn Museum’s Seasonal Inflatable Structure and a visiting professor at the University of California Washington Center. She was a Washington Post art critic from 2000 to 2011; before that, she wrote for Washington City Paper and was on staff at Architecture magazine. Dawson has written for ArtNews, Art and Auction, Interview, and many other publications.