From the early to mid-1960s, in the course of penning a remarkable string of art reviews and essays, Michael Fried formulated the position that much of the most important painting of the day had achieved a “deductive” relationship to the shape of its support. Inspired in part by his acuity to Frank Stella’s adoption, in 1959, of applying paint in stripes that begin at the edge of the canvas and work systematically towards the center, Fried identified similar tendencies in the zips of Barnett Newman and the color bands of Kenneth Noland. Though he would soon ease away from the strictness of claiming that painted form could be logically formulated from the qualities of its support, Fried’s notion of “deductive structure” marks a watershed in the exegesis of modern art. From this moment onwards, critics would increasingly find that the “conceptual tools at hand,” to adopt a more recent phrase from Fried, available to address a particular work of art were increasingly bereft of premises or principles from which deduction was even possible.1

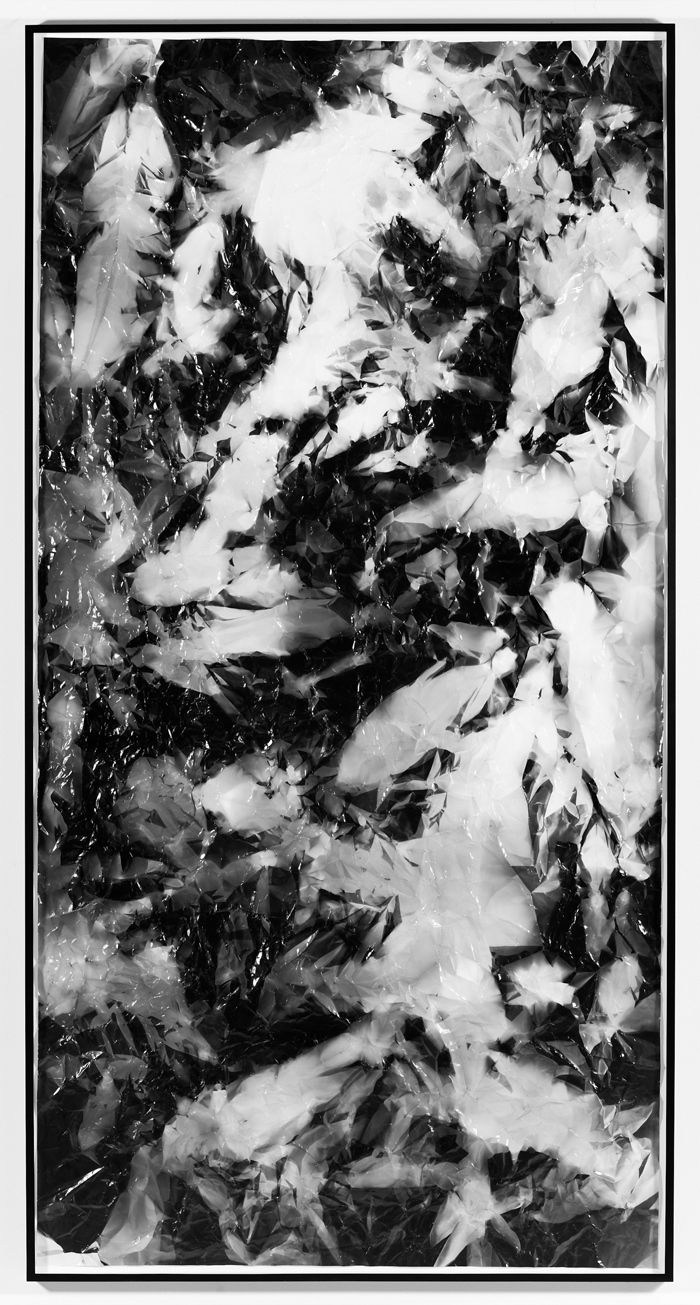

Walead Beshty, Picture Made by My Hand with the Assistance of Light, 2011. Black-and-white fiber-based photographic paper, 55 x 111 ins. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Walead Beshty. Photo: Brian Forrest.

This direction of critical interpretation now seems to have reached the opposite pole. As exemplified by Walead Beshty’s single-artist exhibition, PROCESSCOLORFIELD, at Regen Projects II this past spring, a growing body of contemporary works of art precludes the internalization of aesthetic analysis almost entirely. Encompassing photograms, offset prints, readymade objects, and sculptural relief, Beshty’s variety of new works in PROCESSCOLORFIELD (all from 2011) speaks to a burgeoning network of external attachments in his art that demands closer consideration. Similar to peers such as Wade Guyton and Kelley Walker in their shared investments in printing technologies and modernist typologies of abstraction, and as well to Elad Lassry and Nate Lowman in the free flow of cultural references steaming through their work, Beshty’s art operates at arm’s length to the ethical stakes and material grounding of his numerous working subjects and methods. Contra the condition of art described by Fried nearly a half century ago, it stages a radical exegetic openness.

To examine this condition, I will attend to the colorful photograms, shredded-paper relief sculpture, and metal freestanding sculpture in PROCESSCOLORFIELD in order to tease out the specific manner in which Beshty’s art operates upon external points of reference. Next, we will look to his written work. For, as an accomplished critic, Beshty has provided many of the interpretive threads through which others have received his work to date. Finally, I will conclude by returning to open relation as a broader concern in the circuits of exhibiting and writing about contemporary art.

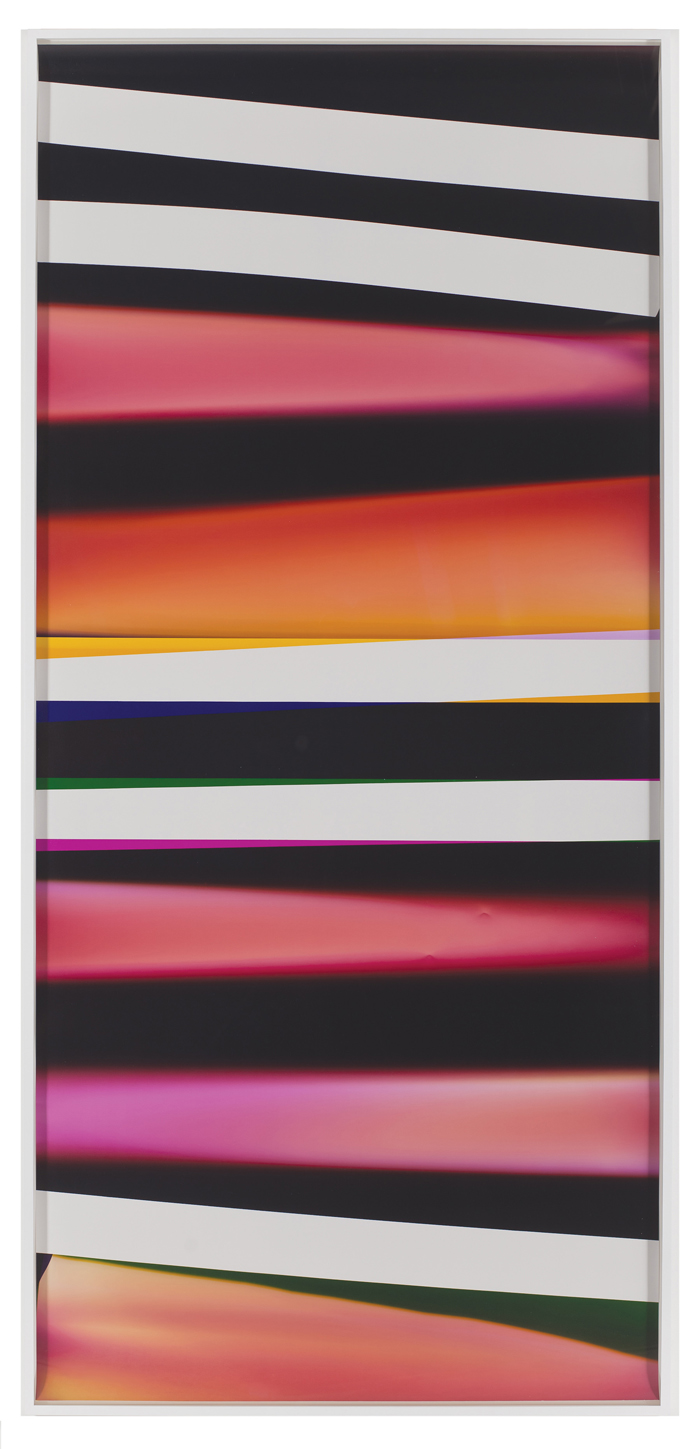

Let us begin with the photograms, which in the last three years alone have appeared in a series of prominent group shows including the Whitney Biennial, California Biennial, Tate Triennial, New Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, and a host of solo exhibitions at galleries and museums across the United States and Western Europe. As has often been recounted, Beshty’s turn to non-figurative photography dates from two events of 2005–06.2 One was the accidental contact of a roll of exposed film he had shot with an x-ray scanner in airport security, which left swashes of bright colors seemingly across the frontal plane of the resulting photographs.3 The other event was a scenario imagined by Beshty and Daniel Hug (then of Chinatown’s former gallery Mesler&Hug) of a folded-paper photogram created by Hug’s grandfather, László Moholy-Nagy.4 Beshty soon began producing his own camera-less works. One series, titled Pictures Made by My Hand with the Assistance of Light (2005–06), in homage to the fictitious Moholy-Nagy photograms, originally consisted of black-and-white images created by directly exposing intricately folded photo-sensitive paper to a light source. After introducing color to this process, Beshty re-named the series Multi-Sided Pictures (2006–). The other body of non-figurative work, Transparencies (2006–), consists of crisscrossing linear patterns and colors created by packing unexposed rolls of film in his airplane luggage, their visual forms a direct result of the film type and the number of x-ray scans (i.e., stops on a given itinerary).

Walead Beshty, Transparency (Negative) [Kodak Portra 400NC Em. No. 3161: April 22–24, 2010 LAX/SFO SFO/LAX], 2011. Epson Ultrachrome K3 archival ink jet print on Museo silver rag paper, 44 x 59.471 ins. Edition 1/1 and 1 artist’s proof. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Walead Beshty. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Where the Curls have absorbed visual and technical aspects of Beshty’s earlier pictures, another of the series in PROCESSCOLORFIELD —entitled Selected Works—operates more directly with the material refuse from his studio. Created by shredding and reconstitut- ing photographic work deemed unusable by the artist, the Selected Works are rectangular relief sculptures formed from the substrate of these re-processed pictures. Each a gnarly mulch of predominately gray paper, appearing something like shag rug left outdoors for a spell, the Selected Works have a sullied quality that might seem out of place with Beshty’s otherwise crisp objects, except, that is, for their thin copper frames. Like the return of a repressed minimalism, precision-cut metal restrains the post-minimal waste in the center of these reliefs, hinting at regularity and reflectivity, and thereby bringing the Selected Works back into conversation with the visual language of Beshty’s show.

Walead Beshty, Copper Surrogate (Table: designed by Florence Knoll, 1961; Regen Projects II, Los Angeles, California, July 17–August 21, 2010), 2011. polished copper, 48 x 81 x 1 1/2 ins. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Walead Beshty. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Walead Beshty, Base for: Copper Surrogate (Table: designed by Florence Knoll, 1961; Regen Projects II, Los Angeles, California, July 17–August 21, 2010), 2011. Powder-coat steel 45 1/4 x 29 x 28 3/4 inches (114.9 x 73.7 x 73 cm); 4 x 32 1/4 x 33 1/2 inches (10.2 x 81.9 x 85.1 cm) pedestal; 49 x 32 1/4 x 33 1/2 inches (10.2 x 81.9 x 85.1 cm) overall. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Walead Beshty. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Other works in PROCESSCOLORFIELD include two interrelated sculptural projects: copper surfaces dubbed Surrogates and powder-coated steel Bases. Each Surrogate had earlier served as a working tabletop in Regen Projects for the duration of an exhibition in either 2010 or 2011.5 Beshty then removed these objects from their supports and attached them to the gallery wall, keeping the smudges and weathering created by daily use. The black Bases, in turn, are the physical stands that had previously supported each tabletop, now displayed on white pedestals. Where the latter perhaps drink in the wordplay of their title at the expense of a more convincing base materiality,6 the former strike at the fissure between object and image that is characteristic of Beshty’s best work. At once reflexive façade and heavy metal object, the Surrogates toe a subtle line between a photographic surface showing the indexical marks of its making and a readymade product transplanted from office to gallery.

In fact, beyond indexicality and the readymade alone, Beshty’s art maintains a wide-ranging interface with twentieth-century modernism. In the case of Marcel Duchamp, PROCESSCOLORFIELD also includes works from a new series entitled Make-Ready (2011–), which consists of offset printing proofs from the publication of Selected Correspondences, one of two mid-career catalogs on the artist published within the last year.7 Each of the Make-Ready proofs features printing variations upon two pages of “content” (mixing both text and image) overprinted on a single spread. Despite the reversal and shift in verb tense upon the “readymade” in their title, the Make-Ready works, like the Surrogates, are more assisted readymades than versions of Duchamp’s original store- bought objects. But akin to the master’s own midcareer repurposing of his earlier works in the 1935–41 Box in a Valise, Beshty’s art as a whole is less engaged with the singular strategies of the readymade and more with an internal communication within his own production. Indeed, the various strategies on display in PROCESSCOLORFIELD emphasize the manner in which Beshty’s art enfolds the forms and techniques of previous works in an ongoing process of expansion.

The art historian David Joselit has written most extensively and persuasively about the networking aspect of Duchamp’s oeuvre.8 More recently, Joselit has turned his attention to types of “signal processing” present in contemporary painting, which also informs the kind of exchange characteristic of Beshty’s work. Identifying a shared tendency in painters including Thomas Eggerer, Guyton, Jutta Koether, R. H. Quaytman, Amy Sillman, and Cheyney Thompson, Joselit argues that “the abstract gesture” for these artists has shifted from “the production of information” in earlier practices of the twentieth century to “now [marking] the transfer of information.” That is, the “content” of their work, so to speak, has become “the very texture of transmission.”9 While the meaning of transmission varies in individual cases, from reflective screens in Eggerer to digital interference patterns in Quaytman, Joselit recognizes the forms of abstraction in their work as consistently operating in the interstices among other nodes of information. Correspondingly, this sense of artistic process as processing is equally characteristic of Beshty’s own modes of production.

We might note, for instance, that PROCESSCOLORFIELD invokes not only the work of Duchamp; as his title suggests, Beshty associates his large Curls with mid-century color-field painting, as exemplified by Mark Rothko or Morris Louis around the turn of 1960. Through more than mere appearance and coincidence of title, this connection is strengthened by the distribution of handouts within the gallery of a short-lived Wikipedia page that correlates 1950s painting and color printing technologies.10 In addition, we could look to the Surrogates as actualizing (or even literalizing) what Leo Steinberg identified in his iconic essay “Other Criteria” as Robert Rauschenberg’s flatbed working surface. Instead of Rauschenberg’s Bed being painted upon and affixed to the gallery wall, in this case Beshty reorients a horizontal, functional tabletop as vertical work of art.11 What is more, by their title, the Surrogates also call to mind Allan McCollum’s numerous groups of monochromes that he calls Plaster Surrogates (1982–). Where McCollum’s works are produced by breaking down the steps of their production (creating molds, casting plaster, and applying enamel paint) as stations along an assembly line, Beshty’s Surrogates address a soft labor characteristic of both service economies and an age of digitized information. Of the Fordist model of production in McCollum’s Plaster Surrogates, it is important that his resulting objects do not bear the physical traces of their making. With Beshty’s Surrogates, we get the inverse effect: traces of the manual work performed upon these tabletops registers upon their surfaces as a process of touch, like so many fingerprints upon a screen. Such processes do not contribute to the material rendering of the objects themselves, only their outer appearance. Here the flatbed experiences another twist. Not only a surface upon which to operate, Beshty’s Surrogates take on the quality of a flatbed scanner, capturing work as image, detached from the manufacture of its physical support.

In and of themselves, such points of reference might provide inroads for thinking about the diverse group of works in this accomplished exhibition, but, given a broader view of Beshty’s practice, the subjects I have identified in PROCESSCOLORFIELD dissolve into a larger field. The kind of inclusiveness characteristic of his overall project is not limited to amalgamating his own photograms, working surfaces, book releases, and even press releases into subsequent works of art, but also to an ever-expanding reflection upon the artistic output of twentieth-century modernism.12 To properly grasp this relation- ship, one must also consider his notable body of written work.

Beshty’s writing has been shaped around a diverse cast of artists, locating in each a kind of mutability with regard to larger currents in contemporary art, and indeed what he says of these others could equally be mirrored back to his own art. An essay on Boris Mikhailov in 2005, for instance, deftly glides past any authoritative judgment of exploitation concerning the Ukrainian photographer’s methods, instead commending Mikhailov’s practice for the very fact that it raises such questions of affect and ethics.13 Similarly, a piece on Wolfgang Tillmans from 2006 discusses the German artist by sidestepping that which is specific to his photography by instead distinguishing various calcified tendencies that Tillmans avoids.14 A discussion of photographer Annette Kelm published last year directly praises her work for “slipping easily into a multitude of provisional patterns, … embrac[ing] loose formal associations, tenuous historical linkages, and personal remembrances.”15

In effect, many of Beshty’s conclusions arrive at and ultimately celebrate the condition of being unmoored. This is the case in what might well be his most widely read piece of writing, “Abstracting Photography,” posted in October 2008 on the blog-cum-print-on- demand-book Words Without Pictures (later published by Aperture). His position reads as follows:

All production—even “authorship”—is comprised of myriad transit points and competing forces which deceptively assume the appearance of solidity. The world we see from transitional spaces— the world outside the window; the world from the perspective of escalators, people movers, monorails, and shopping centres—has become an intellectual bogeyman, a storage container for all our alienations. These infrastructural interstitial zones stand as compromised, indeterminate way stations between chimerical destinations. As an open field they occupy the space of bare fact, which we should approach with suspicion, but they are also unprocessed, and this has potential.16

I would extend Beshty’s notion of the “open field” described in his final sentence to the larger currents of his own practice. We might consider, for instance, the subjects he has chosen for his camera-based photography since 2001: a twice-discarded embassy in Berlin, which previously served the former Republic of Iraq in the former German Democratic Republic; abandoned shopping malls photographed in black-and-white, a somber monochromatic nod to his earlier training with Stephen Shore; side-by-side stereoscopic views shot day-for-night of depopulated modernist housing developments;and overgrown plant life thriving within the discrete zones between intersecting freeways in Los Angeles.17 Whether geographically, socially, or geopolitically, each series manifests a kind “interstitial zone” that we might in turn read as the “way stations” in Beshty’s open fields of production. These are places in transition, just not towards any particular end position.

Together with Beshty’s sculpture and camera-less photography, then, two interrelated versions of open exchange present themselves in his work. One, identified in his writing, pertains to objects and sites with a liminal identity. The other concerns the vectoral quality of his art, referring both to its quality of directing attention elsewhere and his works that involve actual systems of transit.18 That is, both in-between and on the move.

Taken in concert, these two aspects of Beshty’s artistic and critical practices also correlate with a tendency in recent art that Tim Griffin has characterized through the metaphor of digital “compression.” Discussing a diverse group of artists including Pierre Huyghe, Paul McCarthy, Jeff Koons, and Cory Arcangel, Griffin describes a condition in which artistic strategies no longer represent life (in the sense of distilling its experiences into a separable form) nor seek to reveal its frameworks of power (through techniques of signification). For these contemporary artists, Griffin argues, “representation of experience becomes representation as experience.” By “introduc[ing] a degree of representation, or of illusory space, into a situation where reality apparently remains intact, [artists or curators] summon memory while also ‘losing’ the information the site would have seemed to contain.” For Griffin, this amounts to a kind of “compression” in which the addition of new information to a situation overwrites (and, thereby, reduces) its existing code. “The past,” he writes, “obtains a place in the present, but only as a kind of image, and at the cost (or with the purpose) of its becoming detached from historical grounding.”19

Indeed, this sense of loss typifies the liminality and vectoral quality that courses through Beshty’s vast reservoir of historical and theoretical citations, wherein no single term or figure ever fully stabilizes to allow for a consistent ideational framework to take shape. From the various modes of processing on display within PROCESSCOLORFIELD alone, one observes a network of interpretive approaches continually on the move. It is a network that finds coherency, ultimately, in the condition of its own inclusiveness. As the artist recently commented, “The studio is often where things are collected together, where I think through what I’ve done, but I work everywhere and anywhere I can. Sometimes it feels compulsive, but I feel like every moment needs to be reframed within the larger project of the work.”20

From such statements, the question lingers of how one is to judge the openness of Beshty’s practice. Joselit’s account, for one, regards the broadcast quality of the painting he describes in “Signal Processing” in a positive light. Noting his own difference of opinion from Griffin, Joselit writes, “Tim Griffin has recently asserted that a loss of information occurs within contemporary art’s procedures of transmission—a loss that may be understood as analogous to the selective reduction of digital compression. Specifically with regard to painting, however, I think there has been a gain of information through transmission: Significance is accumulated through the reenactment and relocation of the ‘same’ image in different places and times.”21

Beshty expresses a similar sentiment in a recent interview, wherein he accounts for the movement of art historical and theoretical references in his work by stating, “I’m mostinterested in how [artists’] ideas are intercon- nected, in how artists influence one another, borrow from one another, transform and inflect each other’s approaches.” For Beshty, this communal dialogue amounts to his sense that “ideas evolve as they circulate.”22

Walead Beshty, Black Curl (CMY/Five Magnet: Irvine, California, March 26th 2010, Fujicolor Crystal Archive Super Type C, Em. No. 165-021, 07810), 2011. Color photographic paper, 51 7/16 x 111 5/16 ins. framed. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Walead Beshty. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Returning to the work itself, however, the experience of Beshty’s art does not settle comfortably to either side of the apparent possibilities of accumulation-as-compression and transmission-as-differentiation. There is indeed a kind of historical groundlessness in the artist’s world of referentiality that befits the grand-scale loss described by Griffin. But one also cannot help but see Beshty’s myriad output enacting the very kinds of distributive operations we perform every day on digital networks and through the mass transportation of our bodies and our consumable products. These aspects of his practice need not amount to a zero sum game. To adopt Griffin’s language, it is not Beshty’s subjects that are reduced through his production; the compression in his practice takes place in his objects themselves—in the nodes rather than their endpoints. In contradistinction from Fried’s position on deduction in the art of the early 1960s, Beshty’s works distribute rather than ingrain, and as such, must be addressed through their networks. They speak, in fact, to an emerging configuration in art critical interpretation that has been recently identified by Isabelle Graw.

In her 2010 book High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture, Graw discusses a current shift in the relationship between the financial capital of artworks and what she calls “symbolic value” determined by critics and historians. Rather than crudely opposing these two kinds of value, the author instead traces their correlation from the nineteenth century to the present. She finds that numerous historical cases exist of artists such as Gustave Courbet who cannily increased their own market value by prompting favorable reception of influential figures and positively tipping the old axes of supply and demand for personal gain. This relationship, she maintains, remained fairly constant throughout the twentieth century. The major change has occurred only since the 1980s, after which it has become possible to create both kinds of value within institutions of the market alone.

As example of how such valuation now occurs, Graw relates the following story featuring the photographer Andreas Gursky.

In an interview with German news magazine Der Spiegel,… Gursky himself attempted to reinforce the art-historical references in his project, thus (inadvertently) triggering a kind of interpretational chain reaction. In passing, he mentions a visit to a Caravaggio exhibition, during which he realized that in his new “pit-stop” pictures he had unconsciously used “a similar kind of lighting” to no lesser an artist than Caravaggio. This comparison, which blends artistic hubris and art-historical cliché, immediately became standard fare in articles on Gursky…. The mere mention of this name, it seems, is today akin to art-historical ennoblement.23

To Graw’s point, there is presently a distributive framework of writing about art that is maintained, if not required, by the demands of the art world for artists who show in multinational exhibitions, magazine reviews that almost universally support work, museum and gallery texts written on commission, new institutions founded to promote contemporary artists, and on, and on. In such a schema, circulation itself becomes a criterion of valuation.

Walead Beshty, PROCESSCOLORFIELD, installation view at Regen Projects II, Los Angeles, April 16–May 14, 2011. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Walead Beshty. Photo: Brian Forrest.

This effect similarly corresponds to Beshty’s manifold material and textual production. In PROCESSCOLORFIELD alone, allusions to Duchamp, McCollum, and color-field painting would seem to prompt any number of short, comparative accounts of Beshty’s work. And while conducive to the system of criticism described by Graw, the citations in this show, in addition to his many others, typically have no metaphoric or metonymic connection to the larger operations of his practice. That is, by its referential nature, Beshty’s art has thrived under the system described by Graw, but to the detriment of grasping the actual nature of its connectivity. Stated another way, the network of interpretive formats provided by the art world of late capitalism have readily absorbed Besthy’s art, while at the same time, inhibiting the very assessment of its own net of similar operations. In response, I have sought to identify a twofold tendency in this practice that functions through both external vectors (of art historical forms, sociopolitical subjects, bureaucratic systems of organization) and their lack of fixity through techniques of processing and reinscription. Unlike the internalization of meaning described by Fried nearly fifty years ago, the elements in Beshty’s art circulate but do not coalesce into stable explanatory patterns. They instead point to a different approach one must now take to the task of interpretation itself.

It is a mainstay of modernity that significant art stems from the artist going forth into the world. In Besthy’s art, this manner of external being has become constituent to his objects themselves, pushing this very notion of arising from and existing in the early twenty-first century to a point of dispersing the intelligibility of the work of art. One cannot locate in these individual objects a distillation of enduring concerns. One cannot parse their materiality. Instead they exist for interpretation only within conditions located in other sociopolitical formations and late modern works of art. Beshty’s art nonetheless remains utterly of our own historical moment, presenting it to us as so many possibilities leading to so many indecisions.

James Nisbet is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of the History of Art and Society for the Humanities at Cornell University. He received his PhD from Stanford University in 2011 and is currently working on a manuscript that examines the broad role of ecology within advanced art of the 1960s and 1970s.