I treat the photograph as an object, an object to scan.1

–Vija Celmins

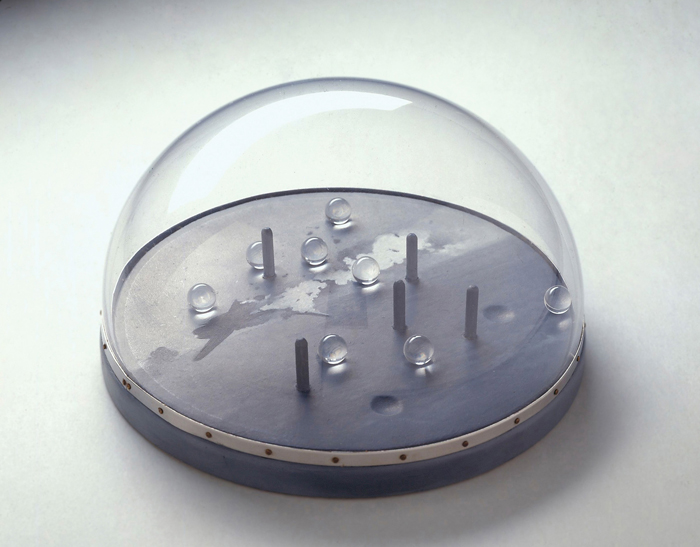

Whatever its merits as a work of art, and these reveal themselves only slowly, Vija Celmins’s hybrid object WWII Puzzle Toy (1965) looks like a terribly exasperating thing to play with. Four inches high and eight inches in diameter, it consists of a circular, horizontally oriented plane upon which the artist has painted the grisaille likeness in oil of some half-toned wartime photograph of a crashing, burning warplane, all encased in a clear plastic dome. Would that we were able to actually play with the thing, the almost certainly futile object of this two-handed exercise in hand-eye coordination seems to be to settle eight clear plastic marbles into the corresponding eight shallow hollows carved into the toy’s floor. This already irritating objective (get one in and three more roll back out!) is made more maddening still by the inclusion of five pegs rising vertically from between the hollows, as if to interrupt any too-lucky marble’s winning trajectory. How carefully we would have to turn this object in hand to succeed in this game! So carefully, in fact, that we would be likely to stop seeing its painted surface solely as image, for all its visual interest, and instead as a surface whose mimetic properties have grown quite subordinate to its objective materiality as a plane. It would require the kind of care that we are all but conditioned to refuse to that whole class of eventful and typically uncredited (i.e., artless), journalistic photographs from which Celmins has painted her toy’s pitted surface and which were the larger puzzle motivating so much of this artist’s inquiry at this moment. If WWII Puzzle Toy is a toy, then, it is so insofar as it evokes the kind of haptic play once necessitated by the daguerreotype, whose image could only be seen (because it was visible only in raking light) once it had been laboriously “cradled in the hand and tilted slowly, right to left, back and forth [to find at last] just the right angle,” thereby forcing in the viewer some recognition of its otherwise rather immaterial photographic source image’s very objecthood.2 Celmins’s handmade “toy” estranges the painter’s source photograph, and more than by virtue of the fact of its being painted, by making it tactile and therefore knowable not as a mere medium, but as a thing.3

Vija Celmins, WWII Puzzle Toy, 1965. Plastic, wood, and oil on canvas; 4 1/2 in. high x 8 in. diameter. Collection of Harold Cook, New York. © 2011 Vija Celmins.

As a rule, the kinds of photographs that Vija Celmins was making paintings of during the period under review in Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster, 1964–1966, make very limited demands upon our attention.4 Though not all, most, and the best ones, are taken from books and magazines. They are by and large eventful photographs; reportage of aerial combat, a riot, a rhinoceros, a man on fire, these exciting kinds of things. They are photographs there only to be glanced at; to be not so much seen as seen through, flipping through pages, and quickly. As photographic objects, they tend to be quite evasive. “Whatever it grants to vision,” Barthes said of these kinds of glanced-at photographs in 1979, “a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see.”5 Or, as Geoffrey Batchen has more recently stated: “in order to see what the photograph is ‘of’ we must first suppress our consciousness of what the photograph is.”6 Invisibility as media is this class of photographs’ necessary condition, its very stock in trade: these photographs report, and they report best when they offer transparency, immediacy, instantaneity—the most direct possible access to their offered-up and ideally spectacular wedge of the world. They are cheap and ubiquitous windows onto some wonder beside themselves. They thus render their own materiality invisible; too overburdened with reference, they are the hardest photographs to see. And with pho- tographic windows such as these, Batchen’s suppression of “consciousness” is precisely the point: their transparency as media is their very ontology.7 So it is unusual, not least in 1965, that such eventful window-pane photographs should be understood as objects, as material, cluttering things. We tend also not to see space-heaters, fans, or lamps; those other things-about-the-studio that Celmins was painting as she arrived at the subject of these eventful photographs. These are things whose function—to make heat, throw wind, and cast light, just as eventful photographs refer—is what little we see in them.8 So such an understanding of eventful photographs as Celmins’s paintings assert requires a particular, unintuitive, and very active sort of looking, a looking against norms. Television and Disaster shows Celmins to have been very good at this sort of looking and very good at eliciting it in us.

Vija Celmins, T.V., 1964. Oil on canvas, 26 1/4 x 36 in.

Curators Michelle White of the Menil (where the show originated) and Franklin Sirmins of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) have devised their exhibition’s title, Television and Disaster, in apt reference to Celmins’s 1964 painting T.V., and they were right to give the medium (television) first billing over its broadcasted image (disaster). Although not the earliest picture in the show (two earlier ones—outliers here—are paintings of Celmins’s own photographs of a friend pointing guns), it was this painting that first really resolves the eventful found- photograph’s material presence over its image-content as the object of painterly interest. T.V. is a painting of an appliance, and in many ways it is a good deal like those earlier appliance paintings. Like Space Heater or Fan (both also of 1964) before it, T.V.—regrettably the only appliance painting on view—presents a functional object of notably immaterial output with a deliberate emphasis on its very functional objectivity. But where with Space Heater and Fan that immaterial output like wind or heat either defied representation or was alluded to only metonymically by the heater-coil’s warm amber, a television’s equally immaterial output posed a different kind of problem. Its output—moving pictures of rapidly unfolding events—was not only immaterial (just a flicker of meaningful light) but also simply too fleeting to avail itself to oil painting’s slow grasp. Celmins’s solution: to fill her appliance’s unpaintable flickering screen with an image (some belligerent midair calamity) painted from a handy picture book’s still photograph.9 It is a bit of studio artifice whose result is the granting of a visible materiality to what would otherwise be the eventful source photograph’s virtually immaterial page. By naming her painting T.V., and not Midair Explosionor what have you, Celmins declared her intentions. The eventful image is compelling enough, but it is nothing—mere static—shy of its decoding box and the space that box takes up, glowing and murmuring among the heaters, fans, and picture books in some corner of Celmins’s cluttered Venice studio. But the painting oscillates between two possibilities: either it is a still-life of a television embellished with the fiction of an eventful image, or it’s a still-life of a published photograph dressed up with the armature of a television to support it. Speaking of her paintings of photographs, Celmins has remarked that she sought to cultivate a level of perceptual ambivalence; offering at once images to be seen through and objects to be seen: “I like the place in the middle where it shifts back and forth.”10 T.V., perhaps more than any other painting in her corpus, achieves this.

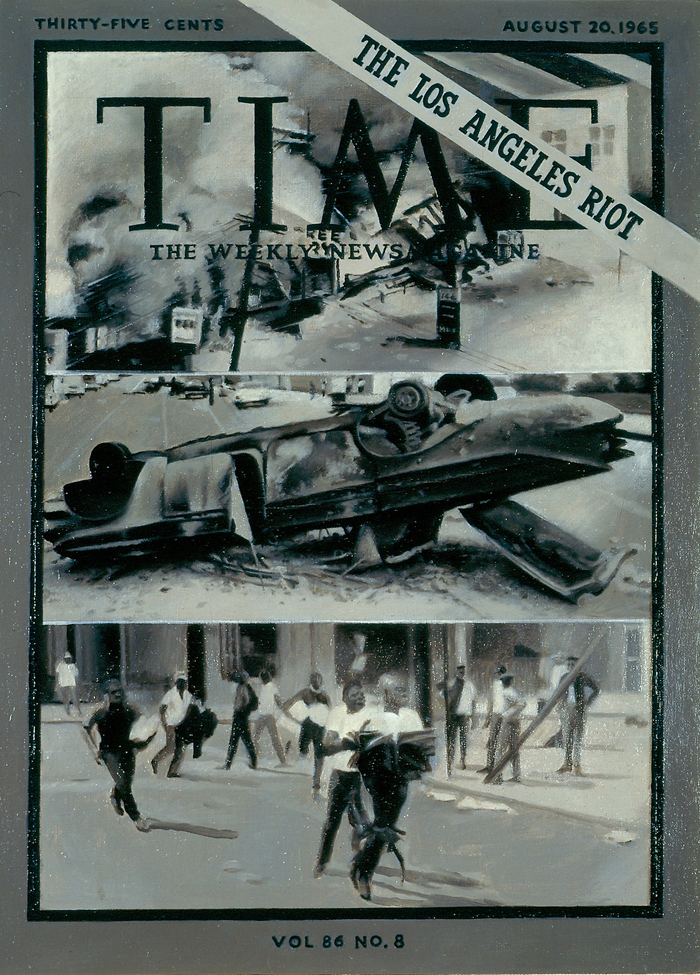

By 1965, while or just after she constructed WWII Puzzle Toy, Celmins was ready to leave behind the photographic appliance and deal directly with the eventful photograph’s more ephemeral glossy pulp support of the magazine or book page. This move is first announced in Time Magazine Cover, a sort of trompe l’oeil still-life painting of the cover of Time’s Watts Riots issue of August 20, 1965. Here Celmins allows photographic flatness to become a feature to be emphasized rather than, as in T.V., suppressed. If it was a salient property of the former functional things that they were bulky objects in space, it was now a salient property of this photographic object that it was (relatively) flat and allover, a thing not to be optically navigated in its depths so much as apprehended all-at-once, like Barthes’s news pictures quickly glanced at; and this is a point that has led to much discussion of Celmins’s place within a certain, dominant narrative of this moment’s Modernism.11 But what must be emphasized is that, for all its apparent difference, Time Magazine Cover is still just a painting of a thing, a sort of Joe Goode-like “common object,” as the curators emphasize, occupying space in the studio, like a television or a space heater or a fan.12 And, as a thing, this particular Time magazine cover was likely a particularly resonant thing, as constitutive of atmosphere as any appliance, featuring as it did three stacked press photographs of that “Watts” rioting in central and southeastern Los Angeles, an affair likely of considerable interest to a person even so far from the trouble as Venice.

Vija Celmins, Time Magazine Cover, 1965. Oil on canvas, 22 x 16 in. Private collection. Courtesy of Hauser and Wirth. © 2011 Vija Celmins.

Taken together, WWII Puzzle Toy and Time Magazine Cover announce an artist with greater aspirations toward photographic looking than the glance; a looking that contends with these images as objects with which one must trouble over in time. This is a very different attitude toward the eventful photograph than we see in the work of many of her peers painting “after” photographs, artists like Warhol whose practices were so clearly couched in a dialectical critique of some Baudrillardian image-surplus.13 Celmins’s painting is closer in spirit to that of her contemporaries Richard Artschwager and Gerhard Richter, whose paintings of amateur and reportage photographs from this same moment “convert,” as Benjamin Buchloh described Richter’s procedure, “the elements of common perception from the spatio-temporal appropriation of the photographic image into an objective material perception, [restoring] perception’s lost objectivity.”14 Celmins’s paintings, then, are not “about” or “after” published photographs so much as they are paintings “of” published photographs—as a field of compelling, cluttering presence—in the way that her hero Giorgio Morandi’s still-lives are not “after” bottles but of them, locating the photographic field itself as the object of perception.15

Vija Celmins, Burning Plane, 1965. Oil on canvas, 14 1/2 x 24 in. Collection of Joni and Monte Gordon. © 2011 Vija Celmins.

Following Time Magazine Cover, Celmins abandoned the inclusion in her paintings of any outward signification of their source’s objecthood—television boxes, toys, a magazine’s branding apparatus—and focused on the photographs themselves, insofar as they had appeared in her books and magazines.16 Burning Plane of 1965, one of several such paintings in the exhibition, is representative of this direction. It is a painting of limited intelligibility, Celmins’s measured touch threatening to obscure the incident—the accidental explosion during the Second World War of a bomb-loaded B-17 before takeoff—to which its photographic source refers. But we know that the particulars of the incident were of only modest interest to the artist. Celmins had turned to World War II pictures because, as she explained in a 1991 interview with Chuck Close, she had been lonely and missed her family, with whom she had experienced that war as a child in her home country of Latvia: “I had been going through bookstores,” Celmins recounted, “finding war books and tearing out little clippings of aeroplanes, bombed out places—nostalgic images.”17 It is a telling turn of phrase, with its object, the things being torn from books and magazines, shifting from “little clippings” to “nostalgic images,” the two phrases refracting equivalence in an slip-of-the-tongue refusal of any either/or that might distinguish matters of content from matters of form.18 But there is in her words, in the end, the insinuation of priority: these bookstore-things were first, in her flow of language, clippings, talismans of—but with no direct reference to—an unrecoverable place and time, and only then were they images.

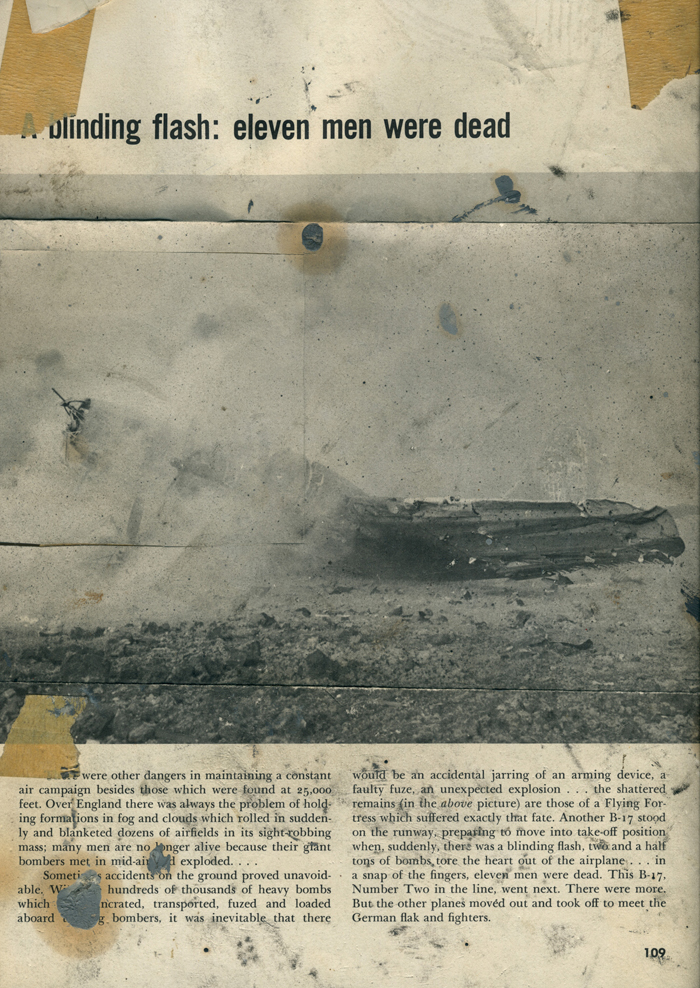

Archival source material from Vija Celmins’s studio. Courtesy the artist.

Celmins’s source for Burning Plane, a page torn from Martin Caidin’s 1957, mass-market history of aerial warfare Air Force, confirms something of the artist’s tactile investment in the talismanic quality of such photographs. It is difficult to imagine a more handled image, filthy with traces of studio use.19 Everywhere are the marks of process, of the taping of the page to the studio wall and the deep scorings that index cropping’s incisions. Through the act of painting it Celmins has made this image a thing bearing its own marks of contingent presence, referring as much to the burning B-17 and its indirect reference to the artist’s own childhood as to its own productive utilization as a thing to be turned in the hand and perceived. Like Barthes’s famous “Winter Garden” photograph, Celmins’s Air Force tear is also “old…blunted…and faded,” a thing to do memory with, certainly a thing through which to encounter “what has been.”20 But for Celmins a different kind of photographic memory work appears to be in play here. Where Celmins’s source images might be safely understood to have offered something like sights of memory (and what instrumental photograph of the past doesn’t make this promise?), Television and Disaster cumulatively suggests that those sights (war, riots, rhinoceroses) were not the artist’s primary concern—certainly her longed-for family was not to seen through them. Celmins’s paintings from these years instead record the activity of looking and in turn grant a careful visibility to their more forthright if rhetorically sublimated purpose: to act as what the historian Pierre Nora has described as lieux de mémoire, or “sites of memory,” those places and objects, like monuments and archives, “where memory crystallizes and secretes itself” just when any authentic link to the once and far-away is severed by modernity’s ever accelerating spatiotemporal ruptures, ruptures that no photographic image can adequately mend.21

Jason Hill is 2011–2013 Terra Foundation Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow in American Art at the Institut national d’histoire de l’art in Paris. He teaches at the Ecole Normale Supérieure.