Looking at Los Angeles from the inside, introspectively, one tends to see only fragments and immediacies, fixed sites of myopic understanding impulsively generalized to represent the whole. To the more far-sighted outsider, the visible aggregate of the whole of Los Angeles churns so confusingly that it induces little more than illusionary stereotypes or self-serving caricatures—if its reality is ever seen at all.

—Edward Soja, Postmodern Geographies1

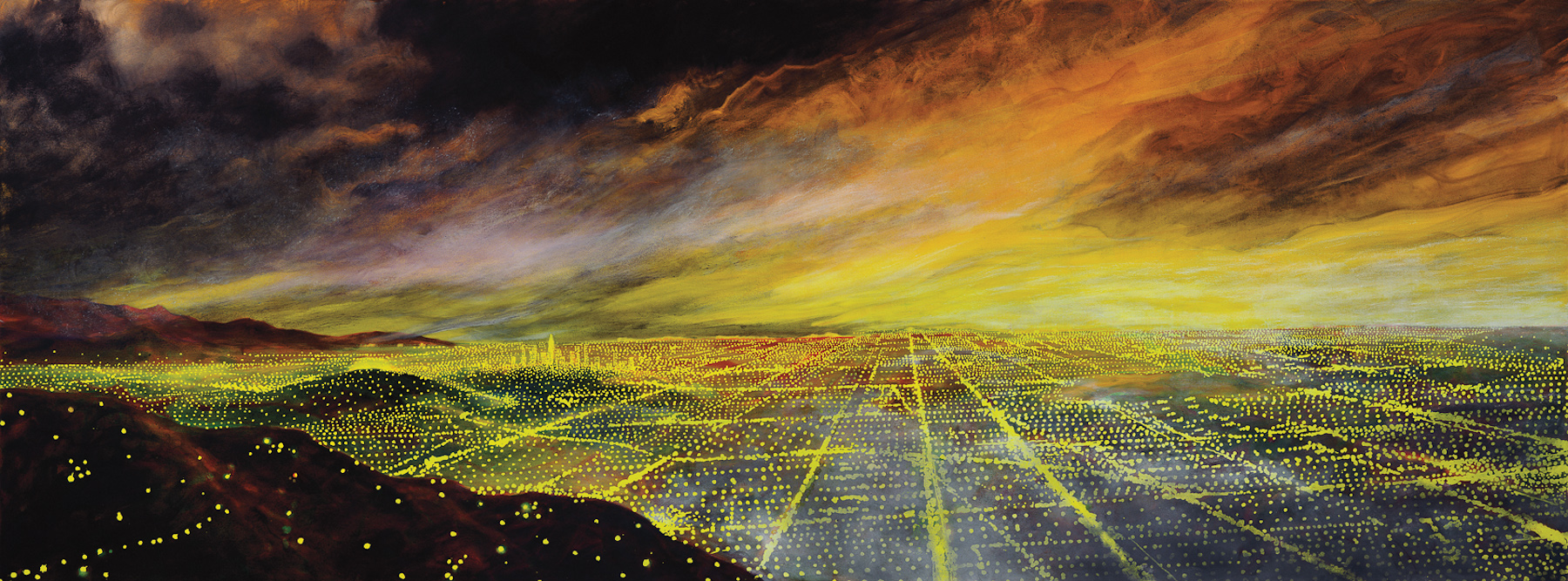

Peter Alexander, PA and PE, 1990. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 75 × 200 inches. © Peter Alexander. Courtesy Pacific Enterprises.

The problem is one of scale. The sheer geographic size of Los Angeles is very hard to grasp, which is why so many accounts of the city fall back on numbers to convey its magnitude. A description such as this might mention the following facts and figures: as a metropolitan region, Los Angeles covers a space of almost thirty-five thousand square miles (twenty-two million acres) and is home to an estimated eighteen million people; as its municipal website proudly proclaims, were Los Angeles county a nation it would have the nineteenth largest economy in the world.2 If such numbers are impressive, they are also abstract and ultimately rather opaque. What, after all, do thirty-five thousand square miles of urban landscape actually look like?

The majority of us probably only understand the scale of Los Angeles as an idea, as much from its long-standing reputation as a megalopolis as from direct experience. Since the 1960s, writers have described the unchecked growth of the city’s suburbs as one of its quintessential characteristics, anticipating with a sense both of awe and revulsion the creation of a conurbation stretching from Santa Barbara to the Mexican border in the not too distant future. In one such commentary, written in 1967, the novelist and historian Wallace Stegner wrote of the unlimited growth that characterized the recent history of cities on the West Coast. Describing Californian urbanism as an amplification of the qualities of the country as a whole, he also saw its accompanying ills. “This is indeed where the future will be made,” Stegner wrote, “with all the noise, smog, greed, energy, frequent wrong-headedness, and occasional greatness of spirit that are so American and so quintessentially Californian.”3 Stegner recognized that rapid expansion also came with serious consequences: a proliferation of free-standing single family homes resulted in sprawl, and the highest car ownership per capita in the country contributed to the already thick industrial smog.4 As it turned out, Stegner’s ambivalence about growth was well founded. Recent years have seen the emergence of a multiplicity of social, economic, and ecological issues generated by the city’s increasing size. The processes of industrialization and deindustrialization have altered and then re-altered the urban landscape; racial tensions and social divisions, frequently exacerbated by the scale of the infrastructural projects instituted by developers, have flared into civil unrest; and the city’s expanding footprint stretching further in every direction raises questions about air quality, the sustainability of food production and distribution, water supply, and a host of other environmental concerns.

Yet for such a central aspect of Los Angeles, its size is difficult to picture. A certain incompatibility between the scale of the city and the finite visual field used to depict it makes the representation of this facet of Los Angeles problematic. This essay therefore sets out to explore some of the visual implications of urban scale. Aptly to its theme, I hope, this account will start big and end up small, beginning with a monumental exhibition at the Getty Center and ending with a personal perspective on one particular image from the Huntington Library’s photography archive. Along the way I hope to use various forms of representation—from exhibitions on its architecture to individual images of the city—as a way to think about Los Angeles’s built environment and the nature of urban aesthetics more generally.

Panorama

Appropriately, our starting point is the Getty Center. From its grand perch above the city, on a clear day you can see all the way down the coast to Long Beach and east to the San Gabriel Mountains, and take stock of the vast swath of land that lies in between. Inside the museum, a similarly comprehensive overview of the city could be found in the recent exhibition Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future, 1940–1990, a survey of the architecture and urban development that made the statistical enormity of the city concrete. The exhibition forms the centerpiece of the Getty’s initiative, Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A., which follows its 2011 survey of postwar art in the city. Pacific Standard Time Presents deals with the city’s ascent to a globally influential position at the forefront of modern architecture and design. Overdrive aims to identify the highlights of Los Angeles’s postwar urban landscape while at the same time illuminating the critical factors that led to the city’s rise.

Michael Light, Highways 5, 10, 60 and 101 Looking West, L.A. River and Downtown Beyond, 2004. Archival pigment print; framed: 40 1/2 × 50 3/8 × 1 1/2 inches. © Michael Light. Courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica.

Foregrounding the idea of vast scale, Peter Alexander’s enormous painting PA and PE (1990) dominates a wall at the beginning of the show.5 Standing six feet high and almost seventeen feet wide, PA and PE depicts a nocturnal panorama of the Los Angeles basin viewed from a prospect in the Hollywood Hills. Its darkness is pierced by thousands of points of neon yellow light, which trace the rectilinear pattern of the city’s streets spread out below. And yet, for all their multiplicity, Alexander’s points of light are clearly nothing compared to the real number of the city’s illuminations, a fact that exemplifies an important quality of most representations of the city: the necessity to edit in order to make its visualization practicable.

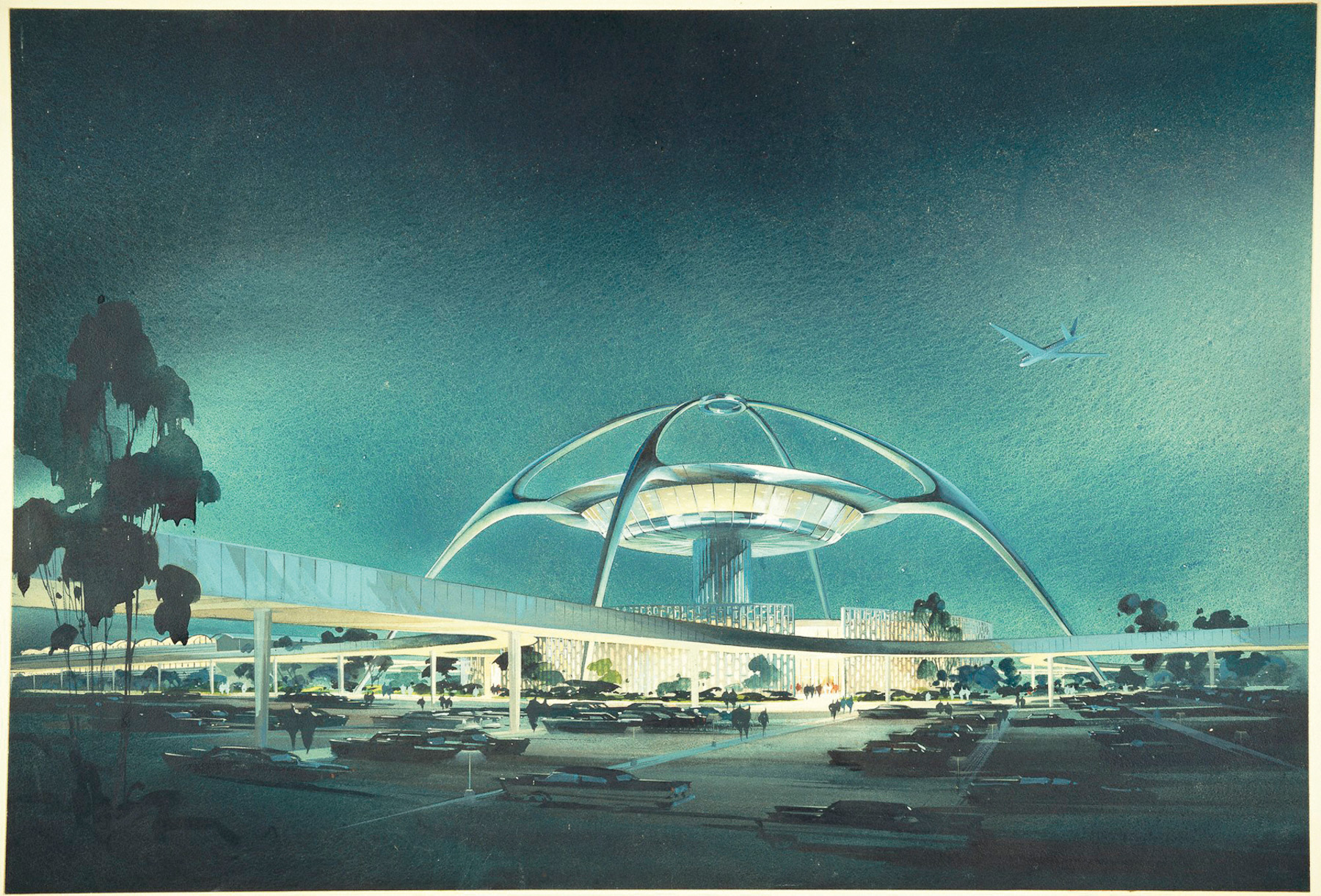

Thus, in spite of Overdrive’s size, a sense of things being scaled down pervades. For one thing, the inevitable exclusions and ellipses of curatorial decision making result in a condensed view of the city: the exhibition’s thesis, that Los Angeles was a global innovator in postwar urban development, produces a compact vision of a sleek and futuristic city. Those familiar with Los Angeles may not recognize this version of the city. On top of this, the prevalence of architectural drawings and models rendering the city in miniature lends the show a feeling of having shrunk the city. The consequent reduction of the enormity and multiplicity of Los Angeles to a manageable size makes its consumption much easier, but the counterpart of this is a failure to perceive the real scale and complexity of the city.

Pereira & Luckman, Welton Becket Associates, Paul R. Williams, and Unknown, LAX, Theme Building; perspective view, 1958. Pencil, watercolor, and gouache on board; framed: 32 1/4 × 42 1/4 × 2 1/4 inches. © Luckman Salas O’Brien. Image courtesy of Luckman Salas O’Brien. From the Alan E. Leib Collection.

The principle of reduction at work here is one discussed by Claude Lévi-Strauss in his book The Savage Mind. Lévi-Strauss uses the example of the model maker to illustrate his argument that reductions in size allow us to grasp things in their entirety. As he remarks, “The intrinsic value of a small-scale model is that it compensates for the renunciation of sensible dimensions by the acquisition of intelligible dimensions.”6 According to Lévi-Strauss, then, scale is a trade-off, with magnitude and intelligibility being two axes on a sliding scale. As he observes, “being smaller, the object as a whole seems less formidable. By being quantitatively diminished, it seems to us qualitatively simplified.”7 If Lévi-Strauss is to be believed, then, true scale and comprehensibility are mutually exclusive.

Such a conclusion certainly applies to Overdrive, the authority and sweeping scope of which conveys a feeling of omniscience, of mastery over the city. Los Angeles and its recent history, seen from such a distance and at such an abstracted remove, seem finally comprehensible. Yet its panoramic overview of postwar architecture, in which highlights are singled out and examined in isolation, also feels distant and unengaged, and crucially lacking in the complexity that is so central to the lived experience of the place. Moreover, the exhibition’s subtitle, L.A. Builds the Future, 1940–1990, prompts us to consider what kind of future has been brought forth by this period of development. In fact, by concluding in 1990, the exhibition effectively isolates its vision of the city from consequences that were just about to rise dramatically to the surface. Most obviously, the Los Angeles riots of 1992 testified to the extent of racial inequality in the city. Other responses to the cultural and built environment of Los Angeles revealed further anxieties about the state of the city that belie the optimism of Overdrive’s perspective: 1992 marked the publication of Mike Davis’s City of Quartz, a trenchant critique of the often malign forces that shaped the city’s urban growth; the same year saw the groundbreaking exhibition Helter-Skelter at the Museum of Contemporary Art, a show filled with disturbingly violent and perversely sexual imagery that unraveled the clichés of the Southern California ideal, exposing the darkness that lay beneath. The important epistemological point about all this is that though the panoramic view seems at first to be a point of expansive visibility, it turns out on closer examination to be cursory and partial, and like the Getty’s hillside perch, a place of isolation.

In microcosm, the same effect is evinced by Julius Shulman’s iconic photograph of the Case Study House #22 by Pierre Koenig, also called the Stahl House, which is featured in Overdrive. The picture is taken from a vantage point on the hillside overlooking West Hollywood; the city extends below, and lights form an irregular grid that recedes into the distance and darkness. In the foreground is a glamorous ideal of modernist architecture: clean steel beams frame an interior space enclosed by floor to ceiling panes of glass; the cantilevered foundation projects out seemingly into thin air. At first glance, the picture seems a simple enough image of the architecture of the city; its setting has become, after all, a commonplace trope of advertising and movie imagery. But its iconicity goes hand in hand with its isolation: floating above the city, it does not seem to be of the city. The photograph’s panoramic backdrop is not a means to connect the house to the wider built environment, but rather a means to create distance from it.

Julius Shulman, Case Study House No. 22 (Los Angeles, Calif.), 1960. Pierre Koenig, architect. Gelatin silver print, 5 × 4 inches. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute (2004.R.10).

A curious and pertinent phenomenon is contained in the following fact. When I first moved to Los Angeles ten years ago, I lived in an apartment on Sweetzer Avenue. By coincidence, Sweetzer is the same street that can be seen running parallel with the line of the roof of the Stahl house in Shulman’s photograph. Yet for the entire time I lived there, I had no idea that this iconic piece of architecture was essentially at the top of my street, and that I might see it, albeit at some distance, by stepping into the street outside my apartment on a clear day.

In fact, the panoramic backdrop of Schulman’s photograph, in common with that in Alexander’s PA and PE, harks back to the prototype for this view of Los Angeles in A Star is Born, the 1954 movie starring Judy Garland and James Mason, in which the nighttime panorama is a leitmotif. Moss Hart’s screenplay for the movie opens with an intimation of the phantasmagoric quality the panoramic landscape possesses: “The piercing beams of huge arc lights sweep the night sky above Hollywood. They circle and criss-cross in a stately minuet of their own; outlining, for a brief moment in a stream of light, the Hollywood Hills, the panorama of the city gleaming in neon below the Hills and seeming, as they flash across the horizon, to endow the legendary landscape of Hollywood with the magic it sends forth to the four corners of the world.”8

In one of the film’s most famous scenes, Norman Maine (Mason) remarks to his young protégé, Esther Blodgett (Garland), that the only fault with her dream of making it as a singer—of having a hit record that goes to the top of the hit parade—is that such an ambition lacks the scale appropriate to her talent. His point is reinforced as the movie’s action cuts at this moment from the interior—where Esther describes what seems to Maine like limited ambition—to an exterior shot with a panoramic view of the illuminated city, her prospects equated with the physical boundlessness of the city itself. Later on, after Esther’s first big movie success, Maine points to a similar vista from a restaurant balcony, “It’s all yours, Esther,” he tells her, “and I don’t mean just the Cadillacs and swimming pools. It’s all yours, in more ways than one.” Crucially, A Star Is Born was one of the first movies to be shot in Cinemascope, a lens technology introduced in 1954 that allowed 35 mm film to be projected in a very wide aspect ratio—up to 2.60:1. This letterbox format (also used in Alexander’s PA and PE) suited the depiction of the city’s panorama perfectly, capturing its formidable horizontal extent. Yet for all its spectacle, a mismatch between the panorama’s appearance of scale and its reality remains. One has only to remember that the inspiration for the nighttime panorama of a fiery, dystopian Los Angeles in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) was the steel works in the small English town of Hartlepool to realize that such appearances can be deceptive.9

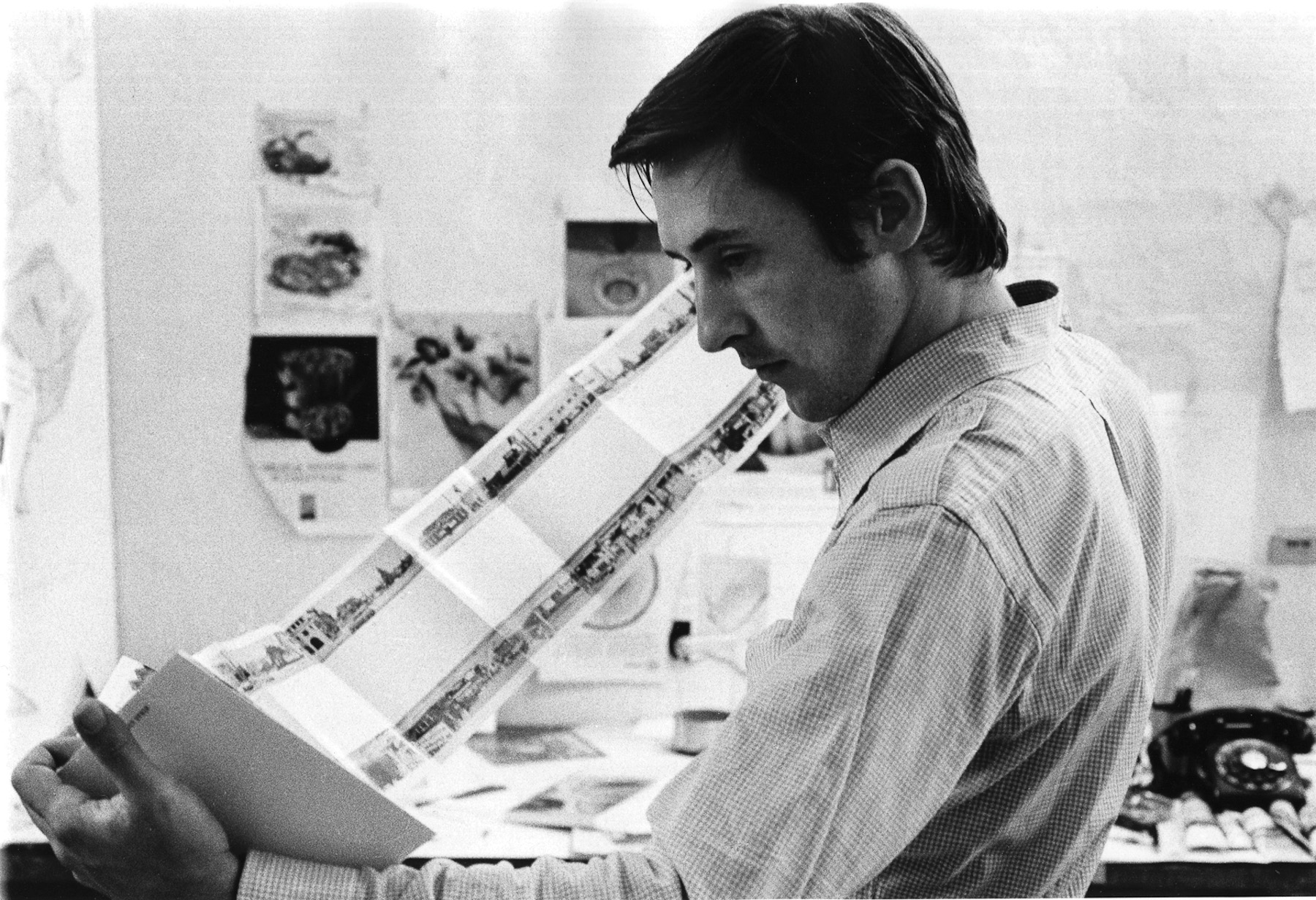

Jerry McMillan, Ed Ruscha Unfolding Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1967. Courtesy of Jerry McMillan and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, CA.

Street View

The urban theorist Henri Lefebvre was all too aware that, regardless of their seeming authority, individual views of the city can only ever be part of the whole picture. In his seminal analysis of urbanism, The Production of Space, Lefebvre sought to demonstrate that the urban landscape was produced by a matrix of separate but dialectically interrelated views and pressures—personal, political, economic, social, ecological—which, taken together, created the city.10 Space, he contended, is not simply transferred over from nature, mere lifeless matter whose spatial geometry is parceled out, bought and sold. Rather, space is produced and reproduced through a complex web of human intentions and interests.

In particular, Lefebvre demarcated three dialectically related ways of representing and constructing space that together constitute the totality of human interactions with the built environment. The one that most closely correlates to the Getty’s perspective in Overdrive is the category Lefebvre referred to as conceived space (l’espace conçu). Although supposedly objective, conceived space reflects a highly determined form of spatial knowledge, usually the product of expert or professional interest. Maps exemplify its form of representation, and urban planners are its typical practitioners. By virtue of its lofty position, such a view sees only the grand vista, the city’s outlines and high points, and consequently risks obscuring the real nexus of cause and effect, the complex and contingent connections that often lie in the city’s interstices.

If such a view of urban space constitutes a discourse on space, rather than an immersion in it, Lefebvre’s other two categories are much more concerned with lived urban experience, and we might usefully deploy them to see how other visual representations of the city diverge from Overdrive’s monumentally conceived perspective. The photo-based book projects of Ed Ruscha, for example, featured in another Pacific Standard Time Presents exhibition at the Getty Center (In Focus: Ed Ruscha), effectively reject the overview and instead embrace the city at street level, in all its humdrum detail. As such, Ruscha’s photographs correspond to Lefebvre’s spaces of everyday perception and praxis—perceived space and lived space (the perçu and vécu, respectively).

A work such as Every Building on The Sunset Strip (1966), for example, shows all the structures on a mile-and-three-quarter-long stretch of Sunset Boulevard between Laurel Avenue and Doheny Road. The work is made up of two continuous ribbons of aligned collaged photographs, one for each side of the street. The space depicted is filled with the vernacular and unremarkable architecture of the period, as well as parking lots, vacant lots and alleyways, sidewalks, billboards, bus stops, and utility poles, among a thousand other everyday details. The multiplicity of ordinary elements does not obscure the fact that the accumulation of such details results in a sense of the city’s immensity. We get the feeling that most of the city is made up of just such sections of unremarkable development. The portion Ruscha represents multiplied by ten would cover the total nineteen-mile length of Sunset Boulevard. Doubling this total gives us a sense of the longest street in the city, Sepulveda Boulevard, which stretches all the way from the north of the San Fernando Valley to Hermosa Beach in the south, some forty-two miles.

When constituted as a book, Ruscha’s photographs unfold from between the covers to reveal the full twenty-four feet of length. This makes the book five feet longer than Alexander’s PA and PE, but even more significantly, because it folds up like an accordion, the entirety of the image is not available all at once—representing, quite literally, the city as a place of continually unfolding representation and perception. What is more, the image demands to be seen up close, from which perspective only a short portion of the street can be seen at a time, giving us a feeling of being in the midst of the action. Even the way the work was made evokes a sense of the landscape as a place always in the process of becoming. Using a 35 mm camera attached to a car, Ruscha produced a sequence of still images while driving slowly down the boulevard, first in one direction then the other. He then painstakingly glued the resulting prints together. Thus, instead of a sequential view of a city, Ruscha’s work suggests a place extending laterally on either side of a mobile subject. To take up our cinematic metaphor again, if Alexander’s work is a panoramic still from a widescreen movie, Ruscha’s view of the city is a long tracking shot.

The work also speaks to the structuring principles at work in the production of urban space: the nitty-gritty of codes, ordinances, and regulations. Though now part of West Hollywood, when Ruscha’s pictures were made in 1966, this portion of the city was unincorporated land and had developed its distinctive nightlife as a result of the less stringent regulation of drinking and gambling this allowed. Later in 1966, strict curfew and loitering laws were enacted with the support of local business owners and residents. The resulting protests and scuffles between police and youths who felt their civil rights were being infringed were later named the “Sunset Strip Riots.” 11 From this view of the city we might extrapolate the multiplicity of perspectives that give rise to its life and space: a complex network of agency reaching deep into the fabric of the city, exercised from a multitude of locations and conceived from a multitude of viewpoints. The aggregate of this accumulation is formidable in scale. Its intricate complexity is almost too much to contemplate, and the idea of controlling or attempting to represent it is an awesome prospect.

Sublime Scale

The novelist Douglas Adams was well aware of the terrifying possibilities of vast scale. In his 1982 book, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (the sequel to the science fiction classic The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy), Adams indicated the threat to sanity that the immensity of the universe holds. To illustrate this idea, Adams created a fictional machine, a technologically advanced torture device called the Total Perspective Vortex, the purpose of which is to reveal to its unfortunate victim his or her precise size in relation to his or her surroundings, cosmically speaking. Thus, when a subject is placed into the Vortex, the entire unimaginable infinity of creation is revealed. Somewhere in it is “a tiny marker, a microscopic dot on a microscopic dot, which says ‘You are here,’” a revelation of insignificance so profound that it annihilated the subject’s brain.12 For the sake of a quiet life, therefore, Adams concluded, most of us choose to ignore the unsettling vastness of the entity in which we live.

Adams’s Total Perspective Vortex owes a great deal to the tradition of the Sublime, an idea popularized in England in the eighteenth century, chiefly by the philosopher Edmund Burke. In his highly influential essay A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Burke described the Sublime as a troubling, energizing, even painful and threatening sensory stimulus caused by the massive phenomena of nature.13 For Burke, such terrifying immensity was most commonly discerned as a property of nature, his chief example, therefore, was the ocean, which, he observed, surpassed even a great plain in sublime power owing to its unfathomable depth. In order to explain its power, Burke pointed to the presence of a divine force in nature that generated the sublime response. In fact, according to Burke, the Godhead—the essential and divine nature of the Creator, regarded abstractly—was the most powerful thing anyone could conceivably contemplate, representing an immensity that not only prohibited the exercise of reason (as all sublime experience does to some extent) but also threatened the total annihilation of the self.

Joseph Fadler, Family at home with little girl sleeping with her teddy bear, n.d. Safety film, 8 × 10 inches. From the Edison Archive. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

In significant ways, the modern megalopolis is an equivalent of Burke’s sublime ocean. Like the ocean, the unfathomable depth and complexity beneath its immense surface area is mind numbing. But if the mind cannot grasp such scale all at once without a loss of reason, it can often put it together piecemeal from individual parts. Arguably, then, the most effective (and affective) way to experience the city is from its aggregate, as an accumulation of individual features on a personal scale. A correspondingly partial and fragmentary, though in total intimidatingly vast, view of the city can be found in another Pacific Standard Time Presents project, an online exhibition organized by the Huntington—USC Institute on California and the West. The exhibition, entitled Form and Landscape: Southern California Edison and the Los Angeles Basin, 1940–1990, is based on photographs from the Edison photography archive held at the Huntington Library. This formidable repository of some 70,000 photographic images, which is viewable in its entirety on the Huntington Library’s website, spans a portion of the utility company’s electrification of the Los Angeles region, from the late nineteenth century to the 1980s. This period of explosive development was captured by Edison’s photographers in a wild multiplicity of ways, from the highly specialized, through the mundane, to the compellingly strange and beautiful.

Because of the size and diversity of the archive, each of the exhibition’s eighteen curators was invited to choose her or his own theme and cull images accordingly. For many of them, the photographs become legible primarily as history, providing a practical, technical, or legal record of a developing technology. As William Deverell and Greg Hise point out in their introduction, the archive thus highlights “the scale, pace, and impact of infrastructural change within the landscapes of modern Los Angeles.”14 As such, the contingent corporate values of Edison are inscribed in real space, offering what Deverell and Hise call “a twentieth century vision of better living through electrification.” The optimism and confidence of Edison’s project is everywhere apparent in their photographers’ vision of the world, corresponding to the prevailing idea that Los Angeles was a preview of the American future—a place of leisure, pleasure, prosperity, and freedom. From a modern vantage point, however, the partiality of this view is clear, its ideological basis exposed. Dianne Harris, for example, in her Domesticity exhibition on the postwar housing boom, identifies the symbolic core of this “fraudulent” American Dream. For Harris, the suburban dream of a clean modern home filled with the latest appliances, a mown front lawn and even, perhaps, a swimming pool, encoded “citizenship, belonging, middle-classness, and whiteness.”15 The photographs Harris and her fellow curators have selected demonstrate the easy reproducibility of this exclusive and racially charged ideal, exemplified in generic imagery such as Joseph Fadler’s People Living in All Electric Home, taken in 1955. Similarly, Fadler’s undated Family at home with little girl sleeping with her teddybear, part of Hillary Jenks Undocumented exhibition, contains a sinister subtext of residential segregation and economic inequality. While on the surface this photograph, with its pastel colors and sleeping child, seems the very image of innocence, wholeness and wholesomeness, seen from a different perspective it comes to embody a pernicious symbol of racial and class identity.

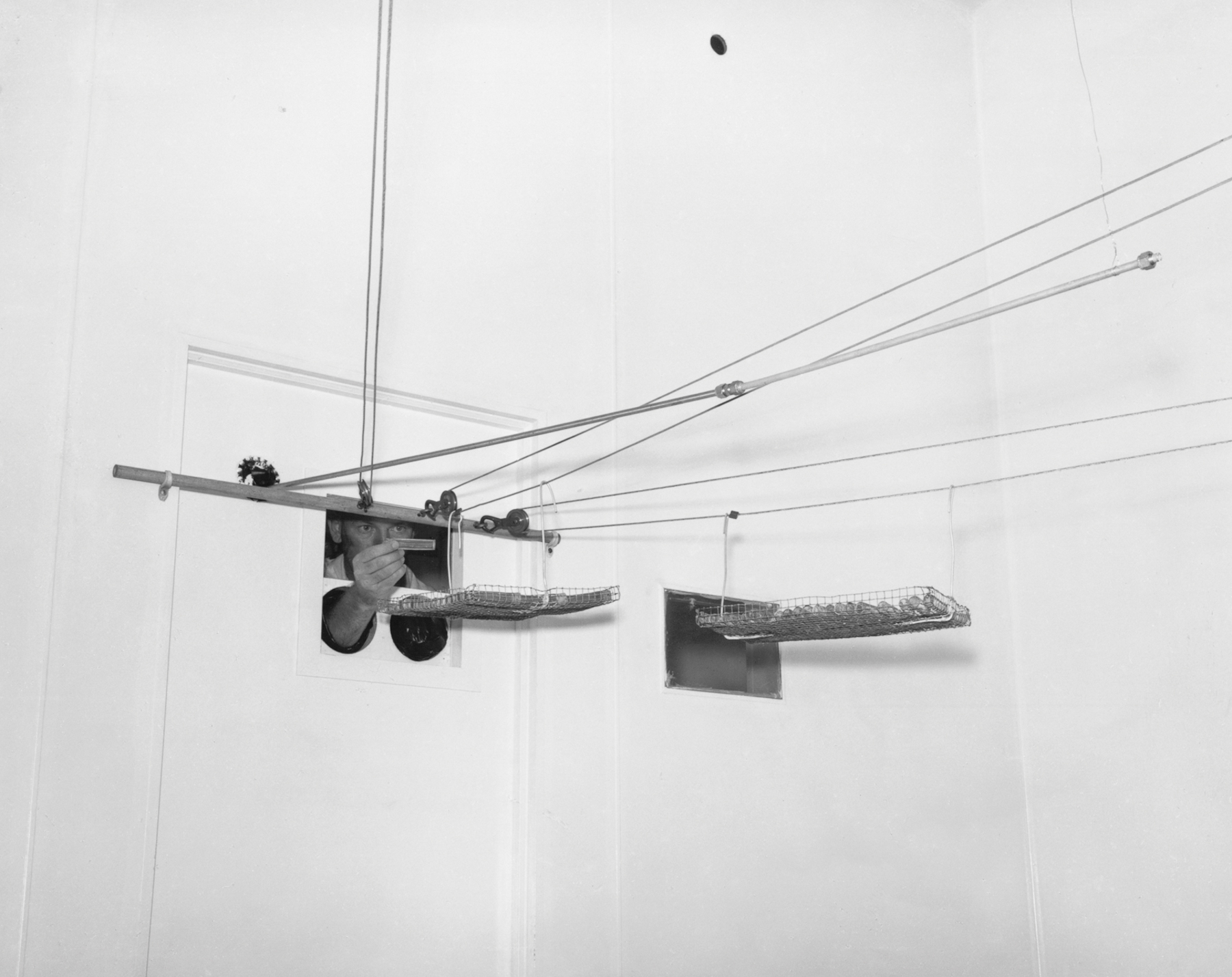

The way images such as this one can take on strange and unintended meanings calls to mind an important prototype for this kind of appropriation of found photographic imagery: Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s 1977 Evidence. Evidence was an exhibition and book project comprised of photographic images from research and corporate archives collected by the artists to produce what they referred to as a “poetic exploration upon the restructuring of imagery.”16Displayed without captions or other identifying information, the images took on an open-ended quality, their meanings unconstrained by a structuring teleology. Jennifer Watts, curator of photographs at the Huntington, invokes this forerunner of the Edison exhibition, pointing out in her curatorial essay that the best of the Edison images “transcend the factual to entice, to suggest, and to challenge.”17 Watts also describes the activity of randomly scrolling through disconnected imagery, which she frequently engaged in whilst overseeing the digitization of the archive. This method of navigating the collection—which anyone can emulate by making her own search on the Huntington Library website—evokes the act of driving through the city, of drifting through unfamiliar neighborhoods or obsessively seeking out new routes and destinations. Such meanderings might get us lost among the multitude of meanings, just as taking the wrong freeway off-ramp might plunge us into unknown parts of the city. But more often we are led back to familiar routes, from which point we can begin to reconstruct our way through the labyrinth. One also thinks in this regard of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up—an important influence on Mike Mandel—and the way its central character becomes obsessed with a blown-up photograph, which he takes as an image of a murder for which there is no other evidence.

Douglas Adams once described his own obsessive nature in terms of a propensity, when turning on an electric light, to think about the journey of the electricity all the way back from the switch, through the circuitry, transformers and substations, all the way to its ultimate origin in the power station. For him the contemplation of such enormous systems as the electrical grid was exhausting, especially when he began to make this connection every time he switched on a light. But Adams’s experience leads us to an illuminating insight into the way we grasp the vastness of the city: thinking about the scale of the infrastructure of the city is a good way to apprehend its total size. Immanuel Kant referred to this phenomenon as the “mathematical sublime.”18 According to Kant, our mind experiences the sublime when at first our imagination fails to comprehend the magnitude of natural events or objects. However, such failure is overcome by the mind’s ability to grasp these aspects of nature by virtue of our reason, resulting in a feeling of delight that our cognitive faculty can stand apart from the enormity of nature and logically reconstruct it.

Close-up

In an essay on Ed Ruscha’s Metro Plots series of 1998, Dave Hickey wrote about the way the narrative of the classic Los Angeles detective story always brought readers in close to the action, burying you so deeply in the text that it often made you lose sight of the wider plot altogether. Such, he contended, was entirely appropriate since the city, like these stories for which it is the setting, is not graspable all at once, but instead appears and disappears through a smog of perception, memory, and (mis)representation. In fact, the beauty of these stories arises from this very experience, from an immersion in the narrative, from which position we can see around us what Hickey describes as the “sublime filigree of interconnections” that constitutes the city.19

Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan, Untitled, from Evidence, 1977. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches. © Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan.

In a similar fashion, the narrative of this essay finally brings us in close to look at my own favorite image from the Edison archive. In its fragmentary and immediate way, it too might cause us to lose sight of the rest of the city, since it shows a snowy mountainside five thousand feet above sea level in the High Sierra of Fresno County, some 250 miles distant from Los Angeles itself. Yet the picture’s connections to the city should not be underestimated, as its location is Edison’s Big Creek hydroelectric facility, a power plant that has provided electricity to the city since the early part of the twentieth century. Captioned in the Huntington catalog as An Edison snow surveyor prepares to force a hollow tube into the snow (no date), the unattributed image shows the man in stark profile against a white background of snow, mist, and fading outlines of the surrounding fir trees.20 The surveyor, clad in snowshoes, looks down intently as he pushes the slender tube into the snowpack at his feet in order to take a core sample. The tube itself, some fifteen or sixteen feet in length, towers over his head, and at its top we see a cross bar, presumably a gauge for taking a depth measurement, forming a cross silhouetted vividly against the misty background. In some ways this is a very utilitarian scene, since it depicts a process of the utmost usefulness to Edison. From this core sample the surveyor will be able to estimate the amount of runoff water that might be expected in the coming spring and summer, a calculation that will allow Edison to anticipate the amount of hydroelectric power available to the system in the months ahead.

Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan, Untitled, from Evidence, 1977. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches. © Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan.

By extending Adams’s obsessive thought process back even further, we can connect the water lying frozen and dormant on this mountainous plateau back to the city hundreds of miles distant. The water that drains west into the San Joaquin River and the Big Creek itself, harnessed by nine Edison powerhouses, produces over 1000 megawatts of power for Southern California Edison, while water trickling east into the Owens River is channeled into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, taking it hundreds of miles south and combining with the Colorado River and the city’s own aquifers to fulfill the boundless water needs of Los Angeles. The aqueduct, William Mulholland’s famous, century-old project, made the expansion of early twentieth-century Los Angeles possible, and the Edison photograph seems to resound to his famously laconic remark on the opening of the aqueduct in 1913: “There it is. Take it.”21Like so much of this imagery, however, it also brings a disturbing subtext. It returns us to Hickey’s Los Angeles noir, to a world where fortunes were made and lost on land speculation, on the prospect of turning barren desert into fertile farmland, the indecipherable world of corruption and greed depicted in Pat O’Neill’s film Water and Power (1989) and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974). Significantly, in the latter film, “Chinatown” becomes a byword for impenetrability, amorality, and incomprehensibility. Both these films foreground the morbid unease about the city that underlies the noir genre. In Raymond Chandler’s work, most notably, the city is a perilously complex and incomprehensible place. Here, his characters are enmeshed in the fearful machinations into which they are drawn, often perishing as a result.

But the Edison image is fascinating too for its abundance of (perhaps) accidental religious symbolism. Alongside the cross formed by the sampling gauge, the gothic geometry of the fir trees in the background seems to evoke a visual rhetoric of faith—the trees’ evergreen leaves have a long history in religious imagery denoting everlasting life, most notably signifying resurrection in the Christian tradition. This combination of fir trees and cross also visually echoes one of the great works of German Romantic painting, Caspar David Friedrich’s Winter Landscape, circa 1811, in the National Gallery in London. In Friedrich’s picture, a crippled man, having abandoned his crutches, prays before a cross that has miraculously appeared to him in the snowy mountains. In the background the spires and façade of a Gothic church loom out of the mist. The picture, therefore, holds the threat of desolation, since the man will surely perish here in this frozen wilderness. But it also holds out hope of salvation, a hope concealed within the commonplace world around us, disclosed only to those willing to open themselves to the perception of the infinite.

An Edison snow surveyor prepares to force a hollow tube into the snow, n.d. Copy negative, 8 × 10 inches. From the Edison Archive. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

We can also grasp a sense of the sublime running through the picture of the Edison surveyor. In this instance, however, the unseen power at work in the landscape is not divine but manmade. The electric power harnessed from water, and indeed the commodity of water itself, were the impetus behind the development projects that forged the modern city of Los Angeles, making it possible to transform thirty-five thousand square miles of semi-desert into a city whose extent now provokes alarm and awe in equal measure. As such, Los Angeles’s urban sublime is inflected with the same sense of hope and despair as Friedrich’s Winter Landscape. While for many of its inhabitants the city is a place of shelter, opportunity, and belonging, it also encompasses forces so massive that, were they to run out of control (as naysayers such as Wallace Stegner feared), they would overwhelm us, plunging us into a polluted, disorderly dystopia. In such a case, Hickey’s “sublime filigree” becomes an annihilating force.

Yet the pictures that most effectively evoke this fear, like those in the Edison archive, also contain the delight that results from any experience of the sublime: they help us trace the city’s complexity, adding up the sum of its infrastructural enormity and confronting our imagination with something limitless and incomprehensible.

Caspar David Friedrich, Winter Landscape, probably 1811. Oil on canvas, 12 3/4 × 17 3/4 inches. © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY.

Jon Leaver is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of La Verne. His research focuses on nineteenth-century French art and criticism as well as contemporary art.