Following the map on the poster-size announcement—or alternatively, getting lost as you wind your way up into the Pasadena suburb armed with only the address noted from an exhibition listing—you may feel a bit more uneasy than if you were approaching a commercial gallery. Once you find the Jamie Residence, the private house Olafur Eliasson chose to present his exhibition, you wonder where to park. Warned that parking is limited, this seems more of a concern than the usual in Los Angeles. Not on the hairpin turn, of course. Too bold to assume you can park in the driveway. Perhaps the slight dirt patch down the hill and around the corner? The experience thus far feels akin to arriving at a party hosted by someone you don’t know—will you have to explain who you are and why you are there?

Eliasson’s exhibition was the first in Milanese gallerist Emi Fontana’s series, West of Rome. Most of his eleven works consisted of experiments involving light projection and glass forms, the majority of which was captivating, some of it strikingly so; but visual character and critical value are very separate in this project. Eliasson’s decision to locate his installation in a domestic space has many provocative implications that extend the critical valences beyond those possible in an institutional setting. Navigating the hills of Pasadena, you are acutely aware that location is a private residence but once inside, almost all evidence of this reality has been obliterated. This is strangely comforting but also perplexing since you cannot avoid wondering what each room looks like normally, and in what ways the house has been transformed for the occasion. Obviously the abundant windows, for which the house is noted, are blacked out, the white walls painted mostly black, and the blonde wood floors covered with black rubber matting. The residence is usually visually permeable to the city but physically closed to the city’s inhabitants; with Eliasson’s project, this situation is reversed. (If you have seen pictures of the Jamie Residence’s interior prior to your arrival, you will be even more disoriented, the transformation being so dramatic.) Is it possible, given the circumstances, to evaluate only the formal qualities of Eliasson’s work as one might be prone to do in a museum?

In this context, Eliasson’s title Meant to Be Lived In (Today I Am Feeling Prismatic) warrants some consideration. The structure is a functional home, although it is also a self-conscious gesture intended to engage with certain other Los Angeles homes. (Architects Ravi Gune Wardena and Frank Escher designed the Jamie Residence in 2000 while they were also restoring John Lautner’s Malin House [1960], better known as the Chemosphere.) There is more at stake than the simple question of: Will someone live here? Rather, Eliasson’s title begs: How would someone live here? Would his setting, with its black walls and dearth of accoutrements, need to be replicated? The function of the space would be, like the panoramic views of Pasadena, essentially eradicated, as the question of “Can this be lived in” would arise.

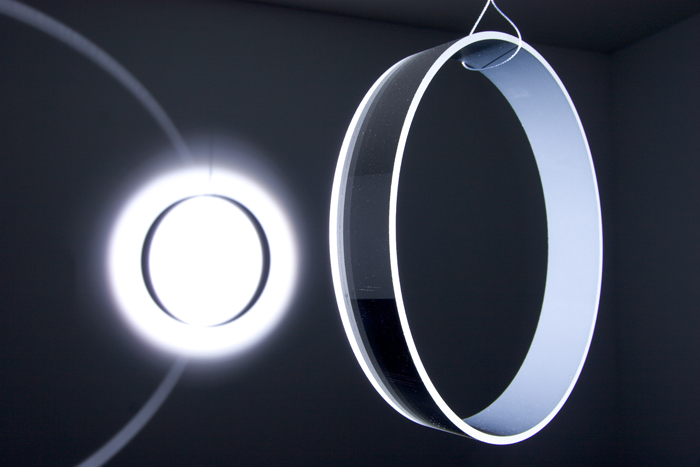

As your eyes adjust to the dark interior, the first thing seen is your doubled and divided reflection; to be immediately confronted with your physical presence within a private space that is not your own is jarring. (Although perhaps to be confronted with your likeness is preferable to the same encounter with a stranger.) But what if you lived with this piece, entitled Yellow Egoless Door (2005)? It does not seem egoless and is clearly not a passageway at all, but rather a functionless partition. That it relies on Halo Window (2005) for its effect seems to mimic the condition of a home in which components must be combined to create a functional living space. Halo Window is best seen during a third pass made possible because the setting causes retraced steps in and out of rooms, affording multiple and multiply revealing approaches. Museums, of course, most often encourage a more linear spatial experience both for concerns of crowd control and to guarantee exit through the gift shop. Despite the novelty of the Jamie setting, however, it also has drawbacks: tight, awkward passages and hot spots, around such works as To Day (2005), that become more noticeable — and uncomfortable — the longer you linger to enjoy them.

Rainbow Spectrum (2005), on the wall opposite Halo Window, consists of 48 framed color monoprints. This addition to the exhibition is striking in that it reintroduces a wide range of color to the home’s interior and makes the space feel more like exactly that—the interior of a home—just by virtue of it being intended for a wall.

Next to Rainbow Spectrum, a doorway leads to a small space housing some components of the piece Domestic Motions (2005), in particular an HMI lamp so blindingly bright in the pitch black it inspires disorientation. A passageway to an adjacent space is blocked by more components of the piece. You leave feeling unsatisfied and a bit like an underachiever, because thus far you have been exposed only to the “backstage” workings of the installation. The full effects of Domestic Motions cannot be experienced until you have exited that initial closet-like space, moved through an entirely different piece (the stunning Your Space Embracer of 2004), and circled into the room previously glimpsed only through the rotating acrylic glass panels. The light effects of Domestic Motions render the room so intimate that if someone unknown to you enters the space, you might very well feel intruded upon. The title references the quotidian paths made within a home. As Daniel Birnbaum has noted of Eliasson: “Even his titles suggest that the works are part of or even a product of the beholder’s conscious life.”1

Away from the first half of the house is the traditional center of a home, the kitchen. Eliasson seems to make a point not to cover up certain native elements such as the stove. An obvious departure from his treatment of the rest of the house, the small kitchen is allowed to mark out the space as domestic. Perhaps Eliasson’s point is to analogize the kitchen as a home’s “backstage area” to the exposed mechanics of his own work. Throughout the exhibition motors, tripods, unpainted wood, and exposed screws all collaborate, as Daniel Buren once remarked, to “dismantle the illusion at the same time that [Eliasson] build[s] it.”2 Eliasson’s penchant for revealing the simplicity and generally low-tech status of his craft forecloses any intimidation and allows for the honesty of the experience to be even touching.

Although the kitchen, in its familiarity, may not normally be intimidating, Eliasson’s installation of two wall pieces makes this area spatially awkward. Garden Mirror (2004) is attractive if not outstanding. Because the narrow hallway does not allow enough space in which to properly view it, the piece becomes somewhat lost. Yellow Triple Frequency Lamp (2005), a glass and steel orb, hangs from the ceiling as would a traditional lamp, but its exceptional girth prevents movement into the kitchen in any productive way. The crisscrossing shadows and yellow glow it throws about are lovely but the cramped space implores you to move away.

This is a relative anomaly in the exhibition and perhaps in Eliasson’s oeuvre in general: a work that deviates from both somatic scale as a frame for personal experience and the scale implied by the context.

Scale is again invoked in a phenomenological sense by Sunset Kaleidoscope (2005). Created in a small window, it is the only work to use natural light and the encapsulated expansive landscape. Sunset Kaleidoscope leaves you feeling small in the face of the bright exterior and strangely large, as if you were looking through a microscope, an effect certainly aided by the home’s high hillside location. To Day (2005) is arguably the most beautiful installation. It is perhaps ironically titled given its proximity to Kaleidoscope and its dependence on darkness to create its hypnotic effect. Its title also recalls the exhibition’s subtitle, Today I Am Feeling Prismatic, which in turn reveals Eliasson’s frequent preoccupation with notions of time, specifically the present. Expanding, contracting, and bending light forms are rear-projected onto a screen that divides a room diagonally. Like Domestic Motions, the experience of To Day is bifurcated. Understandably, its second room seems more pure and spectacular, perhaps because sometimes it is best not to see the magician’s sleight of hand.

Spectral Projection (2005), a lush and painterly, sunset-like light projection, draws attention to an important difference: you cannot see how a painting is made as you look at it in its final form. In Spectral Projection, Eliasson once again uses the how to make a point about why.

Meant to Be Lived In can be simply enjoyed by virtue of its formal aspects; Eliasson’s visual acumen is well developed and the works are, for the most part, enchanting if not visually stunning. Clever and well crafted, they propose a response to the perception-based movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. (Kinetic, Op, Light+Space, and especially the works of Robert Smithson seem obvious influences.) However, Eliasson’s installations are most profound when the viewer engages in a thoughtful act of interpretation that can expose the mechanics of criticism.In a homogenized, institutional setting, awareness of the relationship of object to context is diminished, if not effectively eliminated.

Here, Eliasson forces his work to operate beyond the bounds of institutional formalism to raise questions of how contemporary art relates to modernism and contemporary domestic life. Eliasson said in an interview: “The context is not a matter of definition and should not be seen as a static element; like the viewer, the context is in my opinion to be understood as a progression constantly in dialogue with the viewer…I see the context itself as an indivisible part of my work.”3 At every turn, Eliasson subtly spotlights such issues as what it means to use a domestic space as an extension of a for-profit gallery showroom and how artistic experience can be earned over time. As a result, new critical avenues to institutional critique also open. Critic Jane Ingram Allen has commented that Olafur Eliasson asks a lot of his viewers; at first you might not agree but immersed in the specificity of this installation, you may very well concur and begin your own act of translation and discovery.4

Jennifer Wulffson Goodell is an editor in the Vocabulary Program at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.