“It will take us longer to tear down the Wall in our heads than any wrecking company will need for the Wall we can see.”

—Peter Schneider, The Wall Jumper“Proposals for the other wall were due from potential offerors on

April 4, 2017 and low hundreds of submittals were received.”

—Other Border Wall RFP, Solicitation Number HSBP1017R0023

It didn’t take much foresight, only a little faith in government, to anticipate the two new requests for proposals (RFPs) posted to FedBizOpps.gov the night of Saturday, March 18, 2017: Solid Concrete Border Wall RFP and Other Border Wall RFP. The former stipulated that the wall “shall be reinforced solid concrete,” the latter that the bottom 12 feet shall be “see-through,” but the requirements were largely the same. Both called for designs “physically imposing in height,” impossible for “a human” to climb or tunnel under, and that should “prevent/deter” breach by pickaxe or torch for between thirty minutes and four hours.1 Designs shall be big; designs shall also be beautiful: “The north side of wall (i.e. U.S.-facing side) shall be aesthetically pleasing in color, anti-climb texture, etc., to be consistent with general surrounding environment.”2

As of this writing, not an inch of new wall design has been realized. Yet a rhetorical “fortification” is well underway. “On the fence—it’s not a fence. It’s a wall,” the President told the press on January 11. Two weeks later, on January 25, he signed an executive order to “secure the southern border of the United States through the immediate construction of a physical wall…”3 But when he says “wall,” does he mean “wall”? Within that very executive order: “Sect. 3. Definitions. … (e) ‘Wall’ shall mean a contiguous, physical wall or other similarly secure, contiguous, and impassable physical barrier.”4 (Emphasis mine.) The EO was not law itself, of course, but relied in large part on a 2006 piece of legislation called, with that era’s relatively quaint fidelity to language, the Secure Fence Act. Of the President, journalist Selena Zito observes, “The press takes him literally, but not seriously. His supporters take him seriously, but not literally.”5

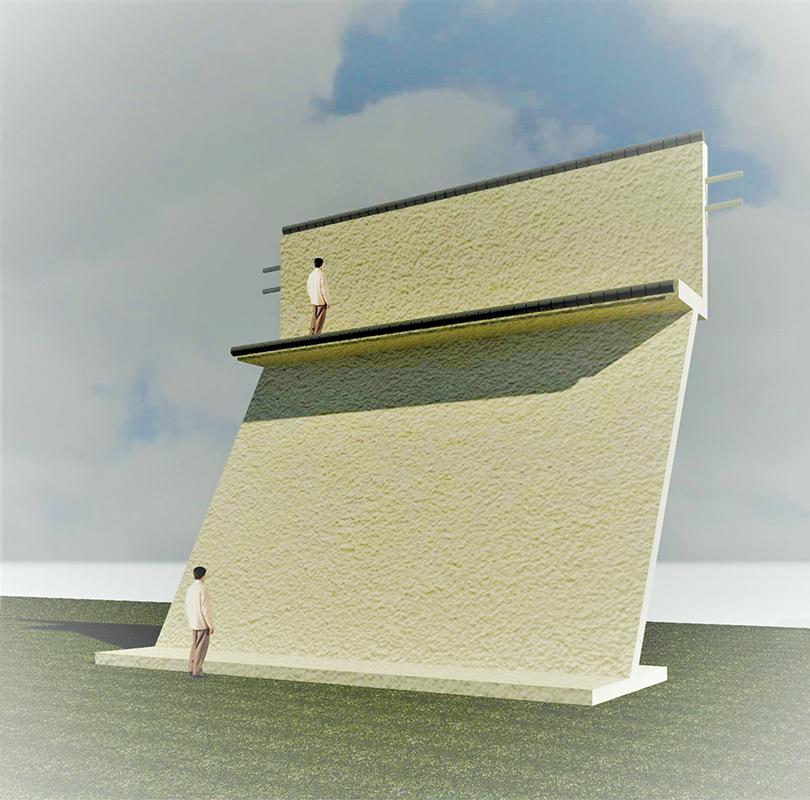

Patrick J. Balcazar, San Diego Project Management, PSC, concept design for Security Curtain Wall, 2017. Courtesy of Patrick J. Balcazar.

There is another function, then, to this insistence that lies and evasions are literally true—that a fence is a wall. Maybe it was worth a laugh to tally up how much concrete, steel, and labor—and how much money—it would take to actually build a border wall that pundits took literally, but not seriously. Indeed, contractors and architects vying to realize the Solid Concrete Wall will need to solve the problem of moving that much concrete to distant, difficult terrain, then casting it in arid climates that regularly reach triple digits and swing forty degrees in an afternoon. But if we take him metaphorically, the unbuilt wall becomes much more formidable. Not an inch of new construction, yet the administration has already taken credit for a reduction in border crossings.6 Perhaps rightly: the economy looks dim and the locals appear virulent. The number of ICE deportations is holding at or below 2016 levels, although the renewed thoroughness of immigration raids, coupled with greater publicity and the open contempt of some agents, has enhanced the climate of fear.7

This symbolic obstacle has been hardening steadily since the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, formally known as the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic. In Ronald Rael’s Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.–Mexico Boundary, scholar Norma Iglesias-Prieto notes that, as the border demarcations changed from a sparse string of obelisks along an “imaginary line” to “a light barbed fence” to “a series of aggressive metal fences and enormous concrete posts,” the Spanish word shifted, too: What was “el cerco, la malla, la barda” became “el muro (it went from ‘fence’ to ‘wall’).”8 Accordingly, when the US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) drafted their RFPs for new barriers, they needed two: the Solid Concrete Wall that insists wall means physical wall; and its pragmatic counterpart, sheathed in its own rhetorical contortion: not to say fence, it is an Other Wall. Together, real fence and rhetorical wall keep others out.

Residents of Naco, Arizona, and Naco, Sonora, play volleyball during the Fiesta Binacional in 2007. Copyright Rael San Fratello; used with permission from University of California Press. Photo: unknown.

—

There is some question about the seriousness of the proposals submitted in response to the RFPs and profiled in the press near the April 4 deadline. Since experienced contractors and sober-minded companies normally would not risk sharing their plans with their competition, the designs publicized by news outlets around the world smacked of self-promotion, protest, artistic intervention, or a crackpot mix of all three. In a proposal represented by a single rendering seemingly made with MS Paint, Pennsylvania’s Clayton Industries offered to build a “moat” of radioactive waste between two fences.9 An Illinois firm, fairly new to the construction business, submitted a “Castle Wall” design that resembles an actual medieval fortification—crenellations and all—plus a bike path on top.10 Another group submitted a wall made of panels cast from local soil and embellished with colored glass on both sides, exceeding the RFPs’ requirement that only the US side need be beautiful.11 Proposals like these took the directives of the US Department of Homeland Security and CBP literally, even in terms of their aesthetics—offering dressed up or themed variations on an ancient technology long vulnerable to ladders and ropes. In 2005, then-Governor of Arizona Janet Napolitano quipped, “You show me a 50-foot wall, and I’ll show you a 51-foot ladder at the border.”12 The border patrol has modified their rhetoric to match: the border wall, such as it is, is meant to delay passage for five minutes or so—enough to increase the odds of making an arrest. In other words, all this for five more minutes.

This idea of a propositional architecture, an architecture that need not be built to achieve some degree of political efficacy, is at the heart of the walls, designs for walls, and stories of walls that Rael collects in Borderwall as Architecture. Many of the stranger interventions Rael describes already exist in some form, such as the Horse Race Wall (two horses, one in each country, running parallel to the border fence) and Wally Ball (at least two volleyball games have used the wall as a net, although Rael notes it was impossible to spike the ball). Others, such as proposals to either incorporate solar panels into a wall design or effectively deploy solar farms as barriers (since they are already, by their nature, highly secure), are echoed by publicized wall proposals and, subsequently, by the administration’s own greening insinuation that the wall might go solar.13 “This book no longer seeks to intervene in the wall’s construction,” writes Rael, “but instead to consider its transformation…into something that would exceed its sole purpose as a security infrastructure.”14 What Rael offers in his book aren’t blueprints (although his innovative wall proposals are feasible in a physical sense) but rather a corrective to the twenty-first century US/Mexico border wall’s glaring failure of imagination.

If words can put up walls, they can also perforate them. In an effort to détourne white European priorities at the level of the word, Rael structures his book after the model of the Grand Tour, “the tourism route for young male European aristocrats” from London to Rome—which, he observes with relish, is roughly the length of the US/Mexico border. “Grand Tourists brought home…books, paintings, and sculpture,” he writes—in other words, art objects, cultural possessions—which “symbolized their wealth and freedom.” 15 Borderwall as Architecture likewise frames the border wall as an aesthetic proposition—not in literal terms of decorative glass, but in terms of ideas deployed as metaphorical structures. He writes, “The recuerdos [souvenirs] created for this chapter are unsolicited counterproposals for the wall, both tragic and sublime, that reimagine, hyperbolize, or question the wall and its construction, cost, performance, and meaning.”16 Rael’s proposals sometimes preempt “actual” (that is to say, solicited) proposals. He describes not only a typology of fences and other vehicular and pedestrian barriers, but also some of the more esoteric “solutions” already implemented, so that they become propositional by virtue of their own weirding weight. In one example, where no “fence” would do, a particular canyon used by migrants was filled with tons of dirt; but a culvert necessary to handle flooding will probably be route enough for people, too.17 (“Walls won’t work,” writes Michael Dear in his contribution to Borderwall as Architecture, “as their creators now concede.” He recalls a visit to the so-called Smuggler’s Gulch project: “The engineer turned his back on the massive earthworks, sighing, ‘Ninety-five percent of this is politics.’”18) Then there is the Sand Dragon, a run of rust-colored steel tubes supported on both sides by long, angled struts, which resembles a giant serpentine ribcage. The design is meant to “float” on the “migrating” sand dunes that stretch between Calexico, California, and Yuma, Arizona. Every so often, a special truck pulls the fence back to the top of the surface, post by post, then it slowly sinks again.

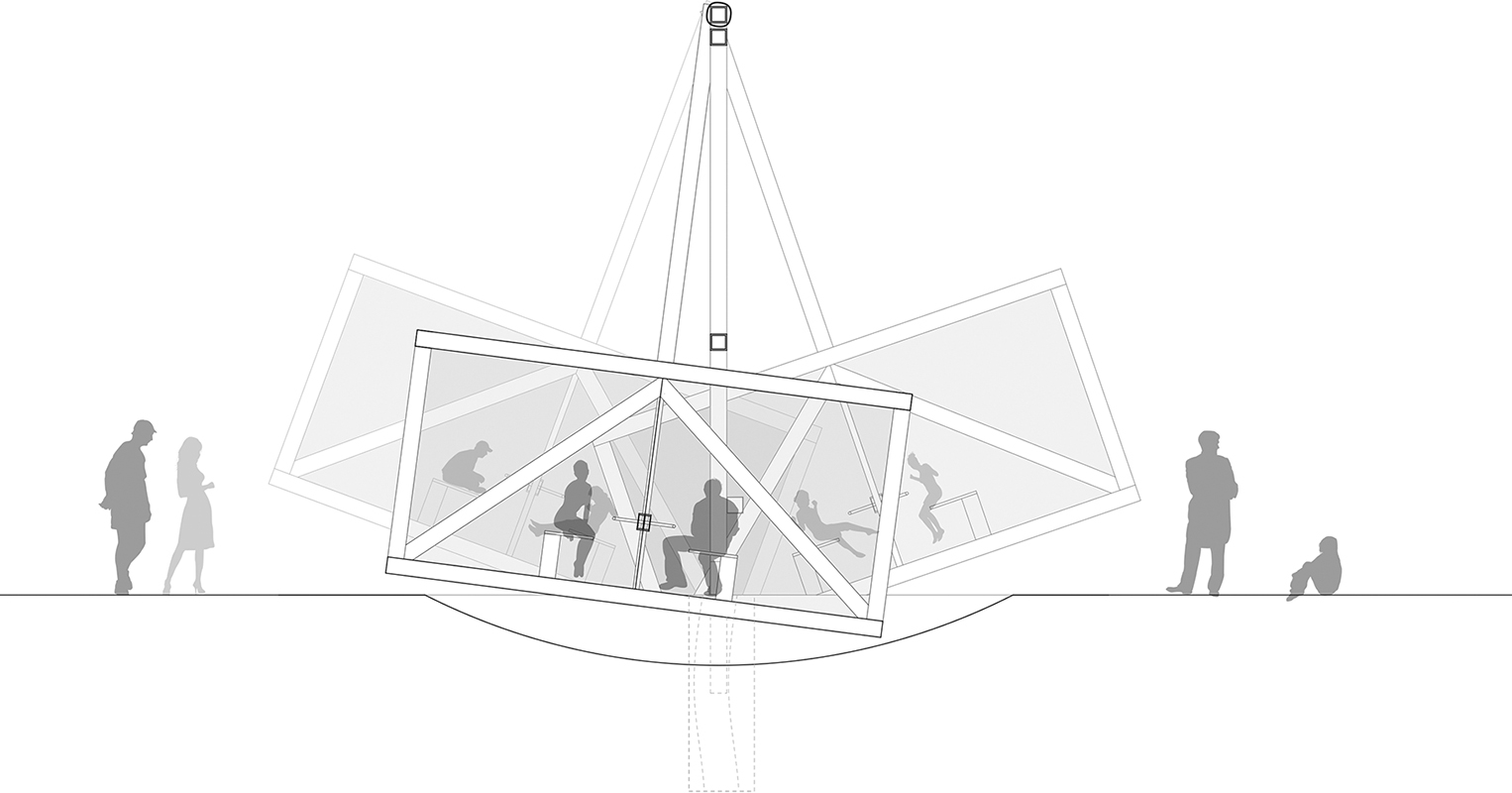

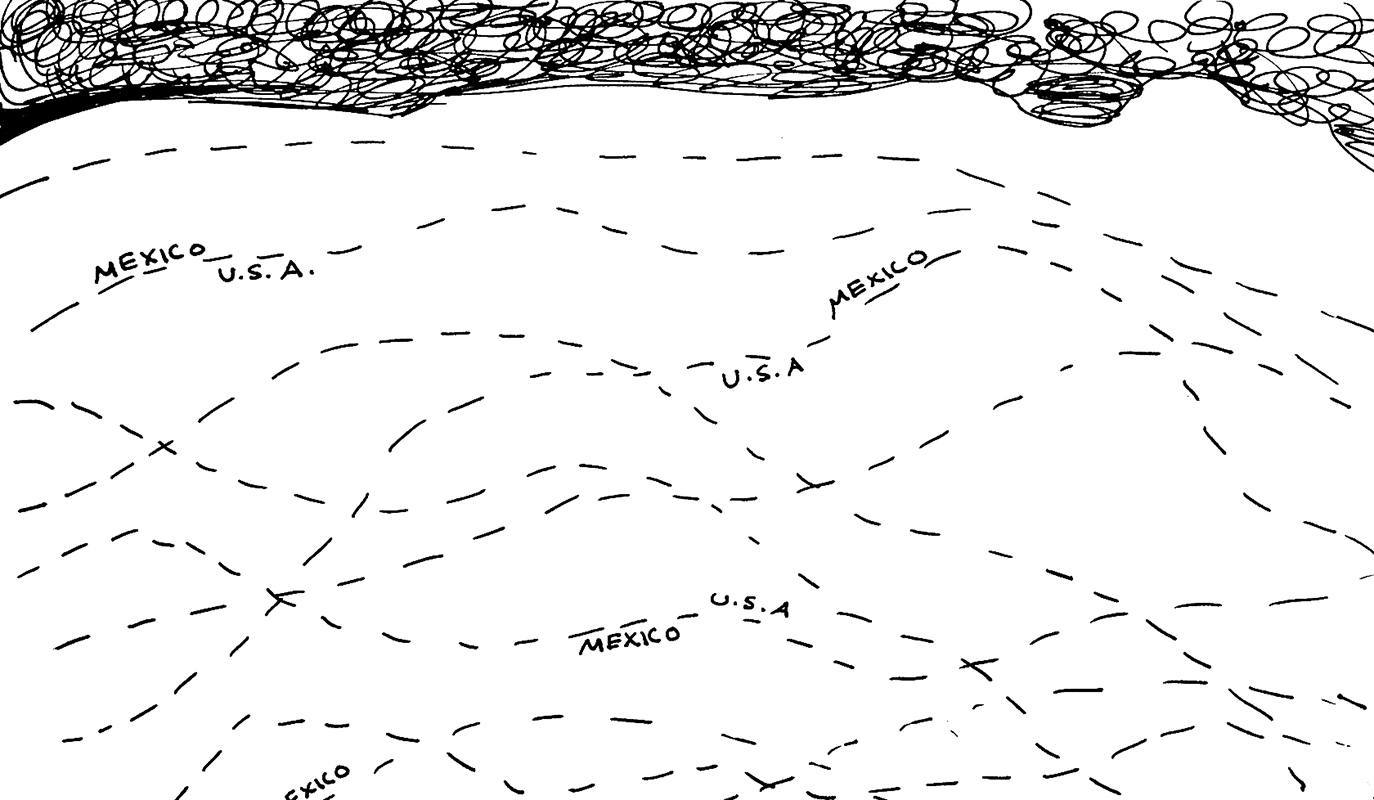

The border wall was a quixotic project from the start, and Rael allows its extant absurdities to smooth the transition to his wackier ideas. Because, perhaps, the tenor of the debate has come down hard, it seems impossible to imagine a Tecate stand straddling the border, or a BP agent buying tacos through the fence. Rael assures us that both have already occurred. These are humanizing moments and evidence of the “third nation” made up of those people with lives split between two countries. The Teeter-Totter Wall, meanwhile—a row of long seesaws with their fulcrums integrated in the fence beams—is too literal to take seriously, since it embodies the balance already found in stranger, more real ways. The Swing Wall, a kind of cage that rocks back and forth between nations, becomes a carnival version of the extant Friendship Park, a circular plaza in San Diego / Tijuana where families can meet across the border that has become increasingly hard to access—increasingly cage-like—on the US side. Rael writes that, on a 1971 visit to the park, Pat Nixon had the Secret Service take down the barbed wire so she could mingle more easily with the Mexicans on the other side. Years later, safely back in Washington, George W. Bush added another layer of fence. The 2017 border wall proposal from Otra Nation to create a utopian “third nation” along the border that issues its own passports, manages migration through biometric security, and features a hyperloop seems a pragmatic statement of how the border region functions despite itself—or how people function in it.19

Ronald Rael, concept drawing for Swing Wall, n. d. Swinging from nation to nation in a binational park. Copyright Rael San Fratello; used with permission by University of California Press.

Rael is also not the first to suggest a Cactus Wall. The idea follows from an interest in sustainable, ecologically sound design; “site-specific” aesthetics; and the fact that the CBP considers natural barriers sufficient. Rael goes further, describing the extent to which Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, which abuts nearly thirty miles of the Arizona/Mexico border, is being carved up—both by smugglers and by the border patrol, who claim sweeping exemptions from environmental regulations. (Nationalism, it seems, is the preeminent land use. Rather than working to avert [or even acknowledge] the looming catastrophes of manmade climate change, the present administration would rather build a bulwark against the mass migrations from the global south that heat and drought will inevitably bring—the sort of humanitarian crisis Europe already faces and that America First enthusiasts fantastically dread.)

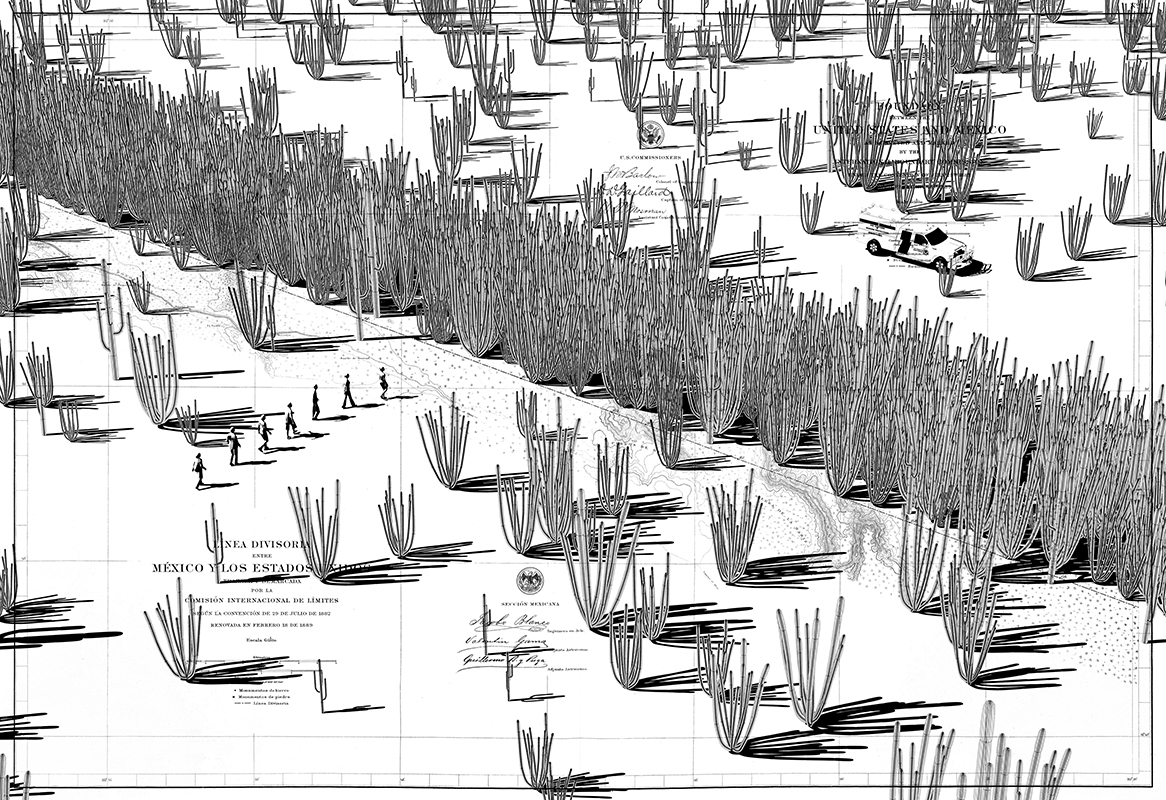

The way Rael illustrates the Cactus Wall is emblematic of his larger project: a grayscale sketch of cactuses, a few migrants wandering toward an impenetrable swath of succulents, a border patrol truck waiting on the other side. The illustration is a concept drawing, populated by the peculiar ghosts that inhabit architectural renderings; it is also, literally, a map—the dense cacti are overlaid on a map of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and surrounding region, so that they appear to grow out of the section of border where they would be planted. The map’s title, BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND MEXICO, is hard to make out against a background of shaded organ pipe cacti. The image superimposes two scales: the territorial and the human, the nationalistic and the individual. And this dissonance is illustrated in a double geographic register: the abstract map and the artistic proposal—one imbricated in the other.

Ronald Rael, concept drawing for Cactus Wall, n. d. Replacing the steel wall with a cactus wall in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument could help to re-introduce native plants to a fragile ecology denuded by vehicles. Copyright Rael San Fratello; used with permission from University of California Press.

—

Back in 2006, on the occasion of the Secure Fence Act, The New York Times invited thirteen architects to participate in a “classic design challenge” to “devise the ‘fence.’”20 Five agreed. The article in which the Times presented the results (with the revealing title “A Fence With More Beauty, Fewer Barbs”) quotes one of the abstaining architects, Ricardo Scofidio, of Diller Scofidio + Renfro: “It’s a silly thing to design, a conundrum,” he says. “You might as well leave it to security and engineers.” For Rael, this is the crux of the problem. If a case for obstruction can be made for engineers and contractors, as Darshan Karwat argued in Slate shortly before the CBP’s 2017 deadline, the same can’t be said for architects.21 “Wall design and construction will, without question, continue,” wrote Rael in March 2016, “but should it continue without the input of architects? Does not participating in the design of the wall make architects as complicit in its horrific consequences as does participating in its design?”22 Rael names the problem common to designing or not designing the wall: an apolitical gloss:

Recently, Archdaily announced, on behalf of the Third Mind Foundation, a competition called “Building the Border Wall.” Perhaps in response to emerging criticism about the ethical implications of such a call to architects, the competition website later added a question mark to the title, changing it to “Building the Border Wall?” Since the competition was announced, as noted by Archdaily, several other edits have been made to the competition website, creating some controversy about the clarity of the competition’s agenda, the position of the organizers, and moreover, the moral implications of the competition itself. What further raises questions about this competition is the organizers’ insistence that they are “politically neutral” to the issue of building a wall along the border and that [they] wish to remain anonymous.23

Quoting Scofidio’s response in Borderwall as Architecture, Rael suggests that firms like DS+R “declined the challenge because they felt it was a purely political issue, something from which many architects shy away.”24 But it’s clear that, as with the wall itself, no one can be on both sides at the same time.

Karwat and Rael reach opposite conclusions for their respective professions, but they agree on an essential point: the wall is unavoidably political, unavoidably public, and therefore unavoidable. In his preface to Borderwall as Architecture, architect Teddy Cruz reiterates that the border wall is a major public work, and a delineation of public space. “In fact, the borderwall is a concrete symbol of an ‘administration of fear,’” he writes, “the most clear evidence of our obsession with private interests at the expense of social responsibility and the erosion of public thinking in our institutions today. This is how the public as an ideal is collapsing within a political climate still driven by inequality, institutional unaccountability, and economic austerity.”25 Rael and Cruz argue that the border wall belongs to the public realm. It is therefore a responsibility for citizens, and for architects in particular, to engage a border wall that is, after all, architecture.

Ronald Rael, a souvenir from the Teeter-Totter Wall, n. d. Copyright Rael San Fratello; used with permission from University of California Press.

With the results of the 2016 election known, President Thomas Vonier of the preeminent American Institute of Architects (AIA) issued a statement pledging to work with the new administration on infrastructure. The organization’s members, including Rael, lashed back. “The statements by the leadership of the AIA can easily and embarrassingly be construed as consistent with Van Jones’ conception of a ‘whitelash,’” wrote Rael, “where the historically white and male dominated profession [of architecture], who’s [sic] diversity is quickly changing, is now attempting to re-align itself with its historic base, rather than embrace its growing diverse constituency.”26 Rael’s letter compares the AIA’s kowtowing response with the priorities of the European style nationalists he later characterizes in his book’s citation of the Grand Tour—before appealing to the better angels of that same culture. “It has been estimated that the 700 miles of borderwall currently dividing the U.S. from Mexico will require $49 billion dollars to maintain over the next 25 years,” he writes. “If we contextualize that amount in comparison to recent major architecture projects in the U.S., $49 billion dollars could finance 300 Seattle Public Libraries, 204 Disney Concert Halls, or 500 Miles of the High Line.”27

Rael devotes a few lines of his book to DS+R’s popular High Line park, again applying a budgetary logic but arriving at slightly different figures. (Rael’s cursory math is somewhat speculative, too; it’s not clear, for example, if he factors in how much of the High Line is refurbished rail bed, renovated warehouse, preexisting stairway, etc.) “It is difficult not to imagine what else an investment of $49 billion could fund along the border,” he writes, “when we compare this cost to recent architecture projects, such as New York City’s High Line—an elevated vertical public park through Manhattan. With capital expenditures expected to be $90 million for the 1.45-mile project, approximately 725 miles of High Line could have been constructed along the southern border, nearly the same amount proposed by the Secure Fence Act.”28 The point remains. Even if DS+R would rather their projects float in a rarefied aesthetic realm—as if the High Line (and their other major public urban commissions, from the Lincoln Center renovation to the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston and The Broad museum) had no political dimension—Rael reinscribes their park back into the world.

So much for a design challenge issued by a newspaper. But what if the RFP is “real”—an opportunity for a government contract to, indeed, build that wall? Between four and eight finalists will construct 20-foot segments of their designs at a testing ground near San Diego. Their prototypes will be blowtorched, hit with trucks, and climbed by government agents with hooks and tall ladders. Then there are the artists. Jennifer Meridian reportedly submitted a handful of designs seemingly hand-drawn on napkins, including for a Pipe Organ Wall and a barrier comprised of Artists Redrawing Border Walls, to the Other Border Wall RFP.29 The #ArtThatWall initiative tried to slow down the wall process by flooding the CBP with silly questions about the call for entries, such as whether fake cacti could stand for real ones in the tests.30 It’s unclear to what degree artists contributed to the general chaos of the RFPs’ uncoordinated rollout, but the initial deadline was pushed back nearly two weeks. The function of these artists’ proposals is not that they were seriously considered or ever had a chance of being built. (Nor, I’d argue, are artists well served by reiterating the stereotype of whimsical artistic interventions in “serious business.”) Instead they function something like the wall itself—as cognitive barriers that give us maybe five, maybe thirty minutes, in a journey where seconds count.

J.M. Design Studios (Tereneh Mosley, Leah Patgorski and Jennifer Meridian), Artists Redrawing Border Walls, 2017. From the series The Other Border Wall Proposals, 2017. Ink on paper and text, scanned and submitted as a PDF document to U.S. Customs and Border Control Agency on April 4, 2017. Courtesy of the artists.

There is another reason to single out DS+R in this regard. Even before becoming starchitects with university buildings and private museums to their credit, the team fielded ephemeral projects like the Blur Building, a temporary pavilion with mist for walls, and Mural, a 2003 project at the Whitney Museum of American Art. (The latter project took place a decade prior to the construction of the Renzo Piano-designed Whitney building that is linked directly to DS+R’s High Line.) In Mural, an automated drill gradually poked holes in the sheetrock, destroying the walls over the course of the exhibition.31 Based on experimental walls of mist and a self-demolishing museum space, the firm was given the chance to design buildings such as The Broad in Los Angeles, which they fitted with a perforated scrim they called the Veil.32 In other words, if ever architects can claim to be mere tools, DS+R never can. They have always worked in the non-neutral territory of the cultural sphere. Further, they have demonstrated again and again a particular attention to challenging our notion of walls—specifically by way of their perforation, literal and otherwise.

It remains to define architecture as any structure that guides or controls our actions. The figurative, conceptual dimension of DS+R’s practice brings it close to Rael’s own project. Good architecture is good not because it gets built, but because it proposes something better than itself. Another wall is possible, says Rael. Words are words, deeds are deeds. Then some words in a budget say the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on, as if the arts and humanities have no real value, no real effect, no “architecture.” Throughout his book, Rael puts the idea of the border wall into play as an aesthetic proposition with tangible consequences. Thus, the border wall as architecture: Don’t design it, don’t not design it; do the third thing: design the wall that will come next.

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He serves on the X-TRA editorial board.