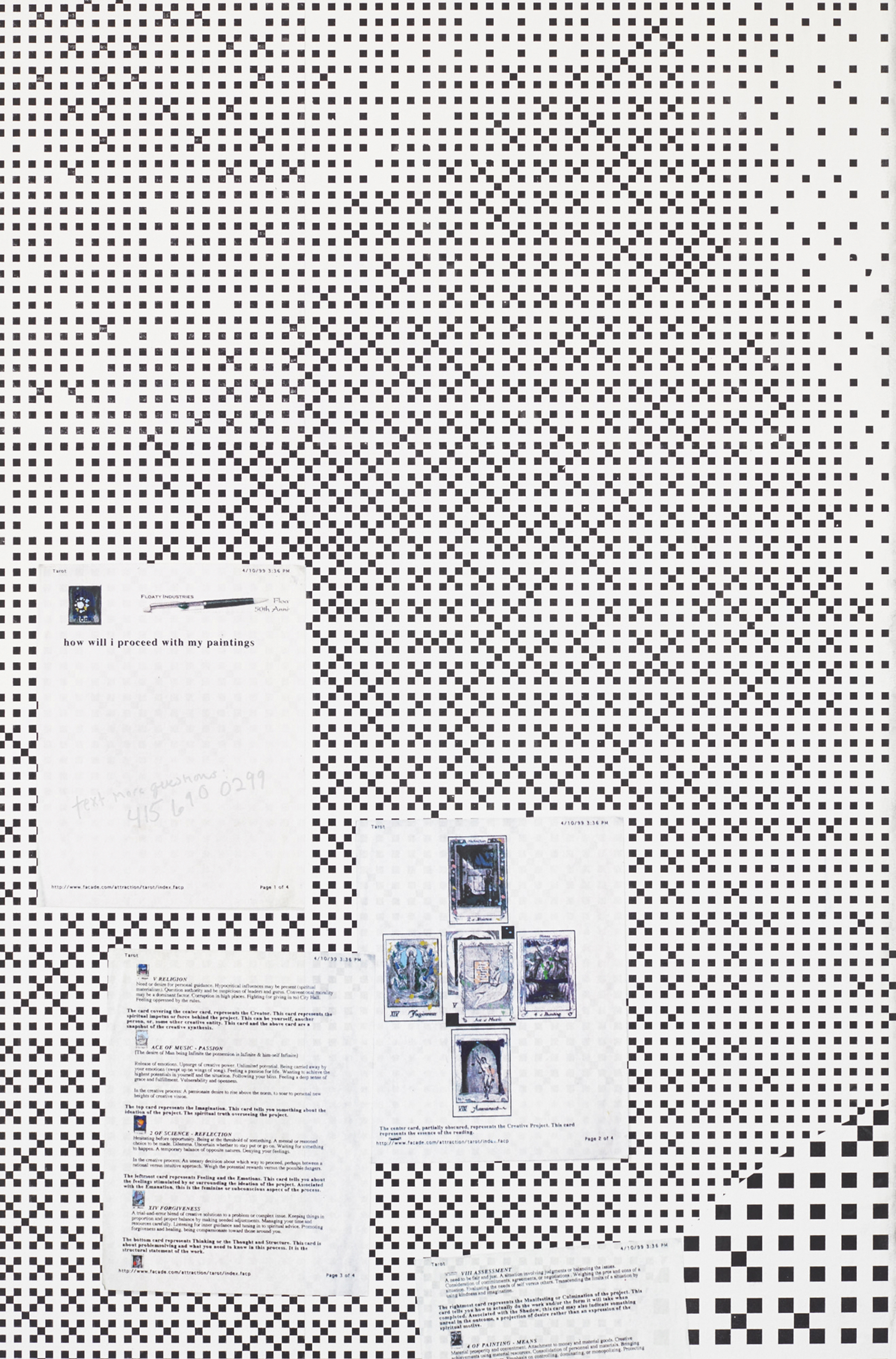

For once, if you wanted to know what the show was about, the show itself could tell you. “Come text a painting,” read the CCA Wattis Institute website in late May, soon after the opening of Laura Owens’s exhibition Ten Paintings. A good first question was: Where are the paintings? Aside from a few dauby abstractions in a back gallery, hung salon style with the artist’s grandmother’s needlepoints (a rocking chair, a schoolhouse, an autumnal mill), Owens’s show comprised a giant silkscreened mural on paper, seamlessly tiled and pasted flush to every inch of the main gallery wall. Tromp l’oeil prints of lumber columns coincided with the gallery’s extant supports. This was less painting than wallpaper, an artisanal digital paradox as much desktop as drawing room, a massive bitmap of gray-lavender texture, layers of more or less coarse grids shaped by hard-edged, god-sized Photoshop brushes and erasers. It looked like not “ten paintings” but a painting—big-screen gestures breaking down into little squares of ink, the whole thing impastoed here and there in toxic-looking neon pigments like a giant hand-touched giclée, the drop shadows on the digital swooshes somehow mocking the actual, plastic buildup. The intimation of kitsch and craft, like grandma’s proto-digital needlepoints, dipped into self-effacement, while the craftsmanship throughout was aggressively good. Scattered everywhere—like scraps on a studio wall, each silkscreened with impressive fidelity—were vintage classifieds from the underground Berkeley Barb, a cat, a Peanuts strip featuring Snoopy’s brother Spike, printouts of webpages, and handwritten notes that urge you to “text any question” or “text more questions” to a handful of 415 numbers.

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic, oil, Flashe, silkscreen inks, charcoal, pastel pencil, graphite, and sand on wallpaper. Ten Paintings, installation view, CCA Wattis Institute, April 28–June 23, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Sadie Coles HQ, London / Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; © Laura Owens. Photo: Johnna Arnold.

This, so far, is quintessential Owens—an attitudinal body of work well summarized in a gallery text by Wattis director Anthony Huberman, here paraphrased in the press release: “When it comes to painting, there are many battles to choose from: flatness versus depth, materiality versus illusion, abstraction versus representation, the epic versus the everyday, the grid versus the gesture. Laura Owens picks them all, and she plays both sides. …She makes paintings that look like paintings. She forces painting to perform tasks other than painting. She feeds painting its own tail so that it ties itself up in knots.”1

Owens lobs a few more shells at the old battleground of “surface.” If pretty art is superficial, decorative, both “flat” and “stupid,” Ten Paintings fits the bill. But this knowing concern for the tail-chasing of Greenbergian Modernism also cues us to the show’s intellectual depth, overwhelming in not only its technical execution (involving seemingly hundreds of unique silkscreen applications) and illusionistic space, but also in the deftness of its art-historical index. The walls were also physically deep; the wallpaper images literally had something behind them: the titular ten paintings. Embedded in the walls, ostensibly awaiting extraction as discrete works of art, were ten aluminum panels.

By the way, you could text the paintings.

Sending a question to one of the posted numbers cued one of an unknown number of scripted audio responses, some general, others strikingly specific, which played from speakers embedded in the walls roughly where the paintings were hidden. Texting “Where are the paintings?” for example, triggered a scattershot chorus of “here, here here, here…” Like Siri’s programmers, Owens anticipated lots of the who, what, where, when, and why of her show—questions like, “How did you make the paintings?” and “Where should I go for lunch?” Yet, even when audible in the white cube’s sloppy acoustics, the replies (something like “I had a good teacher” and “Taco Bell”) were never the answers I wanted. Then again, they were always the quip I deserved for talking to a painting.

Laura Owens, installation view of embroidery and cross-stitch works by Owens’s grandmother, Eileen Owens, made between 1971 and 1995. In Ten Paintings, CCA Wattis Institute, April 28–June 23, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Sadie Coles HQ, London / Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; © Laura Owens. Photo: Johnna Arnold.

The flat, mute image, long derided for precisely these qualities, now adds to its pretense of depth a scripted interactivity. The clues on the walls and the seemingly bottomless “game” of texting paintings hint at a hidden richness: the interior lives of paintings. A program, of course (here in 2016, short of true AI), can only simulate (and perhaps stimulate) conversation. But Owens’s show also models a kind of painterly discourse. As with (other) paintings, there’s a discursive barrier to entry. And what you learn, once there, is that there are no last words. An artist proceeds from an unanswerable question of a set form—the “painting problem,” for example, of which Owens plays all sides. A peevish answer can be just what we need to maintain motion across time—to overcome the fatigue that maybe we’d like to blame on all this superimposed media, the layered and merged historical styles, cell phones, classified ads, web psychics, and the Adobe Creative Suite. In this respect, Ten Paintings’s insidery attitude, its veneer of information and secrets and gimmicks, is both Owens’s latest innovation and the work’s least productive aspect. After all, how much info do you really want? How far will you go to “discover” the “secrets” of these “paintings”? Rather, it’s the open-ended anxiety of secrets left covered and questions left unasked that prompts a more fundamental and unsettling problem: What is it you want from art, anyway?2 As if asking something of Art in the abstract is any less insane than asking paintings directly, or texting your question to a decorated wall is substantively different than standing there looking at it and wondering, what’s the point?

“[T]ext more questions / 415 690 0299” reads a note seemingly handwritten on a computer printout, then rendered on one wall. Heading the page in a digital typeface is the phrase: “How will I proceed with my paintings.” It’s Owens’s own question to a tarot card website. The bot’s reply fills a further three pages, listing and describing the six cards from the William Blake tarot (the recommended deck for writers and artists) arranged in the cruciform layout of the Creativity Spread. The first, for instance, the center card, “partially obscured, represents the Creative Project. This card represents the essence of the reading.” Owens has drawn “V RELIGION”: “Need or desire for personal guidance. Hypocritical influences may be present (spiritual materialism). Question authority and be suspicious of leaders and gurus…” The answer, like those of the paintings, isn’t direct or specific—that’s how tarot works—but the general wisdom can be bent to anyone’s situation. The spread isn’t final, but procedural—another prompt.

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic, oil, Flashe, silkscreen inks, charcoal, pastel pencil, graphite, and sand on wallpaper. Ten Paintings, installation view, CCA Wattis Institute, April 28–June 23, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Sadie Coles HQ, London / Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; © Laura Owens. Photo: Johnna Arnold.

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic, oil, Flashe, silkscreen inks, charcoal, pastel pencil, graphite, and sand on wallpaper. Ten Paintings, installation view, CCA Wattis Institute, April 28–June 23, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Sadie Coles HQ, London / Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; © Laura Owens. Photo: Johnna Arnold.

More than painterly considerations, however, what I most wanted to know is why, in a largely formalist and contemporary show, on a gallery desk otherwise scattered with little ceramic emoji faces and copies of the exhibition text, was there a yellowed copy of a January 17, 1991 Los Angeles Times, where the headline announces the start of Desert Storm? I’ll admit I asked the paintings. They were unhelpful. I’ll also say I called the 805 number printed on a postcard-scale version of a poster by Sister Corita Kent (a nod to another stunning graphic artist), that reads, in the sky-blue sky above an ochre path through brushy hills, “we can create a life without war.” On the first try I got a busy signal. (A landline? It’s like I called the 1990s.) Later, I tried again and reached an office answering machine. I couldn’t understand the man on the tape when he said his name. I was curious, but I wasn’t actually that curious—and I didn’t leave a message. Maybe that was my answer.

FOR HELP DIAL “0” / Anyone who thinks he can manage alone, he’s an idiot. / The Sure One—Sister Corita Kent, the sure one, 1966

Fitted to the illusionistic wooden column in a back corner of the Wattis gallery is another overlay—a list of 29 handwritten names (plus the word “Puto’s” [sic] and an arrow); all but three names are crossed out, including the last entry: Laura. The list has been lifted from graffiti on a concrete column in the basement of 356 S. Mission Rd., the gallery in Los Angeles that Owens co-founded.3 One column cues another. In San Francisco, Owens’s ten paintings stood mutely or babbled or broke into Gregorian chant in the airy Wattis space.4 Back in Los Angeles, the denser, darker cacophony of Lutz Bacher’s four-channel video PLEASE (LC) (2013–15) clamored in the dim yellow basement of 356 S. Mission Rd. A clip of Leonard Cohen peering out from a blue curtain and singing a bar was repeated in semi-random sequence across four projectors. In the center of the room rose the show’s titular Magic Mountain (2015), a head-high pile of spikey blue modules of acoustic foam. Designed to muffle the walls of a recording studio, here they weren’t absorbing much.

Installation view of Lutz Bacher’s Magic Mountain, 356 S. Mission Rd., Los Angeles, May 21–July 31, 2016. Courtesy of the artist, 356 S. Mission Road, Los Angeles and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

As you passed through a heavy-gauge plastic curtain and ascended the stairs to the main 356 S. Mission Rd. gallery (a larger and rougher version of Wattis’s refinished warehouse) the loud plucky scrap of Cohen crossfaded to the light dirge of a piano being tuned. In the middle of the space, like the basement works’ bright “doubles,” sat a trio of more heavenward pieces. Paradise (2016), a baby grand piano painted white and rigged with a speaker, played the sound of its own tuning.5 Aligned approximately one floor above the castoff Magic Mountain, The Alps, 2015, a billboard-scale mylar print, shiny and translucent, of sharp snowy peaks against a relentless blue sky, trailed down lengthwise from the rafters to the concrete. Glitter covered the floor and dusted the windowsills and electrical outlets—a work titled Divine Transportation (2016).6

Such cheap, readymade transcendence scraped away where visitors dragged their feet and hitched a ride on shoes and clothes, winding up transported to your face, your car, your apartment. Magic, then divinity, then paradise, Bacher’s gestures feel loose and grandiose, promising more than they deliver—a conceptualism both gnostic and punk.

Installation view of Lutz Bacher’s Magic Mountain, 356 S. Mission Rd., Los Angeles, May 21–July 31, 2016. Courtesy of the artist, 356 S. Mission Road, Los Angeles and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

Earthly toil is never far away. Bacher, like Owens, “intervenes” in the gallery desk. Thirteen found chairs (Chairs, 2016), of a simple welded-box-type design and painted in flaking copper, silver, and gold, have replaced the gallery’s usual office seating at a long table in the front room. Pasted to the wall behind it, in a Leonardesque tableau, is a roughly tiled blowup of a found photo of several turn-of-the-century gentlemen around a table. Bacher mirrored the old image horizontally, to make it a biblical thirteen chairs (six of the seven in the original photo appear twice), but 22 men. Over the years, the source print had been etched with graffiti; possibly the subjects had given themselves nicknames, or later owners had added insults. Both long tables—one extant, one photographic—evoke, maybe, the Last Supper, while at the same time leaving this an absurd coincidence. It’s a silly photo, after all—one man poises a gavel above his neighbor’s head, another points a banana like a gun. It’s a warehouse, not a church. Trying to find some greater meaning in Magic Mountain is like asking God for a lunch recommendation, and getting a reply: “Taco Bell.”

Lutz Bacher, Godfathers, 2016. Inkjet print on paper, 80 x 46 inches, and Chairs, 2016. Paint on metal, 32 x 6 x 6½ inches each, 3 total. Magic Mountain, 356 S. Mission Rd., Los Angeles, May 2–July 3, 2016. Courtesy of the artist, 356 S. Mission Road, Los Angeles and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

In recent years, Bacher has organized panel discussions on her work as part of her exhibitions. At 356 S. Mission Rd., three panelists met behind this very table.7

Like God, the artist is present only indirectly. Instead, audience members may ask questions of her panelists, who are likely just as baffled as they. For a talk to complement her 2013 show at the ICA London, a participant began by quoting “expressions of dismay” from Bacher’s reviewers, including the essential: “How are we supposed to view the work of Lutz Bacher?”8 Like God, the artist doesn’t give interviews (only the occasional oblique press release). Instead, she conducts interviews with friends and collaborators.9 She asks the questions. And if the artist herself is somehow an answer to her art, this too is withheld; Lutz Bacher, famously, is a pseudonym.

Lutz Bacher, Sweet Jesus, 2016. Sound installation. Installation view, 356 S. Mission Rd., Los Angeles, May 21–July 31, 2016. Courtesy of the artist, 356 S. Mission Road, Los Angeles and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

“The exhibition continues downstairs and outside,” reads a sign. Like “text more questions,” it’s an admonition and a challenge. Four speakers are mounted in an asphalt side lot; over a tightly looped, New Age chord progression, the patented velvet voice of James Earl Jones, slightly slowed, intones the begats that introduce the Gospel of Matthew. (In the 42 generations from Abraham to Jesus, only four women are mentioned—in the form “begat X of Y.” The feminist invective, too, is nearly readymade.) The piece is titled Sweet Jesus (2016), after the star of both the begats and the New Testament, but among Bacher’s more rhythmic or stuttering edits is a marked hairpin turn in the lineage, right before the finale. In this version, Jacob begat Joseph, then Jacob begat Joseph again, then Matthan begat Jacob.10

Topped on two sides by barbed wire, the parking lot is less prison yard than a little slice of desert, complete with knee-high sunbaked weeds. Forty-two minus one is forty-one—a numerology for which, no matter how long we wait in this wilderness, Bacher offers no Messiah. Or at least we won’t live to see it. That’s the post-spiritual penance we can rightly expect of contemporary art—where all answers are trivia, all questions prayer.

X—

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He serves on the X-TRA editorial board.