The International Cairo Biennale is no transient art-world fad, but rather an established institution of over twenty years that has recently been carving a place for itself on the international scene. For its 11th installment, the organizational process and the artwork selection were restructured in an attempt to better reflect the diversity and complexity of contemporary art.1 In its transition to a new format, the show was somewhat uneven. Yet its significance and interest were concentrated in a selection of several very strong works, and the promise that the new format holds in the rapidly growing art world of the region. As Khaled Khafez—a member of the organizing committee, a central figure in the Cairo art scene, and an artist in his own right—notes, the selection committee curtailed the tradition of displaying hundreds of individual pieces by limiting their selections to approximately eighty artists, in order to allow for the increasing centrality of installation art and to better reflect the practices of painters and sculptors by representing bodies of work in greater depth.2

In the interest of disclosure, I co-authored a catalogue essay with U.S. Commissioner Kimberli Meyer for the United States’ presentation of Jennifer Steinkamp. Prior to my arrival in Cairo, I consulted on public programming for the U.S. presentation. For the purpose of this review, I examine artworks by artists with which I was not involved.

The majority of artworks in the Biennale focus on social concerns, from the perspectives of the global, the local, and the personal as political. For the foremost artists of the exhibition, media is not a transparent mode of communication, but rather the subject of analysis. Noticeable is a heightened awareness to the ideological functions of the photographic image and its immense influence on identity formation. Lebanese artist Khaled Ramadan’s humorous mockumentary Wide Power (2006), for example, presents a montage of personal photographs, while a voice-over narrates his life-story in relationship to media. An outgrowth of a childhood craving to have his picture taken, Ramadan’s initiation into adult consciousness is intertwined with his growing awareness of photography’s place within power dynamics. Throughout Wide Power, the artist observes the position of the camera as apparatus, activity, and documentary tool within personal, social and political hierarchies.

Adel Abidin, Tasty(still), 2007. Cardboard boxes, DVD player, projector, semi transparent projection surface, four active speakers and sugar cubes. 6 minute loop. Installation at Cairo Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2008-09. Courtesy of the artist. © Adel Abidin.

Adel Abidin, Tasty, 2007. Cardboard boxes, DVD player, projector, semi transparent projection surface, four active speakers and sugar cubes. 6 minute loop. Installation at Cairo Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2008-09. Courtesy of the artist. © Adel Abidin.

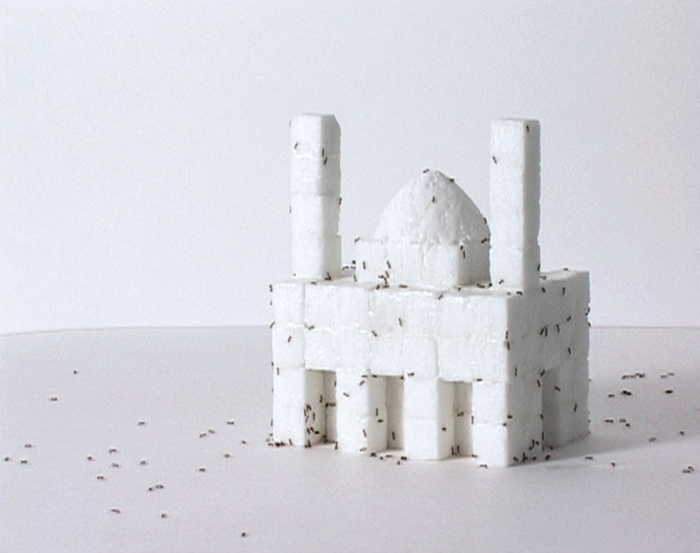

In many of the Biennale’s artworks, humor underlies serious subject matter. Referencing the play in Marcel Duchamp’s Why Not Sneeze Rrose Sélavy? (1921) on the cognitive difference between seeing, feeling and tasting, a video by Adel Abidin (born in Baghdad, lives and works in Finland) called Tasty (2007) depicts a model of a mosque constructed from sugar cubes, which is projected onto a screen assembled from white cardboard boxes. Positioned near an off-screen anthill, the on-screen mosque is crisscrossed by ants, which threaten to consume their sweet host. At moments, the assembly of tiny insects looks like a long-distance shot of attendees gathered at a religious event, an image familiarized by broadcast news. The play on scale becomes a comment about the deceptive potential of media—how it warps our sense of scale and distance, perceptually or otherwise.

Winner of a Biennale award, the video projection Oil and Sugar (2007) by the French-born representative of Algeria, Kader Attia, shares the subjects of the media and, coincidentally, sugar. In a tightly composed shot, sugar cubes arranged into a neat cube on a tray slowly topple when black crude oil is poured over the top and seeps through the cracks. The video employs materials that have specific socio-geo-political significance, referencing a history of cross-cultural economies that are necessary and constructive as well as those that are colonialist and destructive. The texture, shine and scale of the image create a mesmerizing effect that resembles footage of natural disasters or buildings being demolished, reminding the viewer that a mediated spectacle may elsewhere be a tragic reality.

Lara Baladi, Borg El Amal (Tower of Hope), 2008. Ephemeral construction and sound installation: symphony, bricks and cement, 9 meters high. Installation at Cairo Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2008-09. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Lara Baladi.

Constructed on the grounds of the Palace of the Arts is Egyptian artist Lara Baladi’s Borg El Amal (Tower of Hope) (2008). This nine-meter tower and sound installation, made of red brick and National cement, embody the paradoxes at the heart of a socially engaged art practice. Baladi’s tower, which is modeled after the informal domestic architecture that sprawls endlessly on the outskirts of Cairo, comments upon the city’s expansion along the Nile, which is pushing agriculture and rural life further away from the metropolis.

Emulating the architecture of survival, the tower is nevertheless majestic in its appearance, its proportions and open ceiling inspiring a sense of awe upon entering. Inside, one can sit on cast-concrete benches around the perimeter and stare upward into the sky, an experience that becomes almost spiritual at night. Yet, the transcendental qualities of the work are tempered by its mimetic qualities. Because Borg El Amal is so reminiscent of the urban landscape, it also reminds viewers who take pleasure in it of the privileged position of art, and art’s ability to distance poverty.

Lara Baladi, Borg El Amal (Tower of Hope), 2008 (detail). Customized brick for the project, ready to be cooked. Cairo Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2008-09. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Lara Baladi.

This contrast is underscored by the work’s soundtrack of soprano voice, cello, flute, and violin, composed by Nathaniel Robin Mann and Angel Lopez de la Llave, as inspired by Henryk Górecki’s composition Symphony of Sorrowful Songs #3, Opus 36 (1976). The music disrupts contemplation, as its striking tones are punctuated by the recorded braying of donkeys. Banned by officials from the city’s center, the beast of burden also returns as an image pressed into some of the tower’s bricks. Despite its contradictory aesthetic, the mix of braying donkeys and poignant modern music is seamless, underscoring the aesthetic contradictions at the heart of the project. Winner of the Biennale’s Nile Grand Award, Borg El Amal achieves a delicate synthesis by allowing for a physical experience of pleasure and transcendence while serving as a socially engaged, non-reductive artwork.

Perhaps more so than any other biennale host, Cairo cradles the art in its immensity and history, demanding multiple interpretations and providing endless instances of questioning. Many of the artworks on view encourage a critical approach to the process of visiting and looking. The representation of social issues central to this Biennale orients the visitor as she steps out into the city to soak in its thousands of years of history, her awareness of her position as an observer finely tuned.

Dr. Nizan Shaked is an Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art History, Museum and Curatorial Studies at California State University Long Beach. In 2008, Shaked (along with three others) received an Emily Hall Tremaine Exhibition Award for How Many Billboards on the Boulevard?, a large outdoor exhibition of commissioned billboards slated to launch in 2010.