This is the second part of a two-part interview with Laura Owens that took place on March 28, 2013. The first part, which was printed in X-TRA, volume 16, number 1, concentrated on 356 South Mission Road. This section focuses on the paintings she created and exhibited there.

Laura Owens: We’re talking only about the building and the idea of 356 South Mission, but I want to return to the paintings. It was my intention to try to show my art here, because I’d been shipping work over to Europe and I hadn’t shown in Los Angeles for ten years. I felt like I was not a part of the conversation here.

Stephen Berens: There’s a sense that you want people to think about these works together, and the exhibition is set up so you can do that. The paintings are very close together given their size, right? There’s the idea of trying to have an exhibition wrap around you.

Jan Tumlir: In any other medium, everything is not in there—not in the frame or in the material or in the object. In a photograph, for example, there’s always something going on outside, but everything that’s in a painting was put there by the artist, and that’s all there is.

LO: And you know where it ends.

JT: Yes, but then you deploy a number of moves in these new paintings that function almost to blur that dividing line between inside and outside.

SB: And you employed some motifs in these paintings that are, like, twenty or thirty years old.

LO: Yeah, there’s some drop shadow action.

JT: The shadows are ridiculously convincing. I don’t know if it’s because of the scale of the paintings.

LO: Oh, they’re next-level drop shadows, for sure.

SB: And then there are the edges of the white paintings that make them look almost like they’re stuffed.

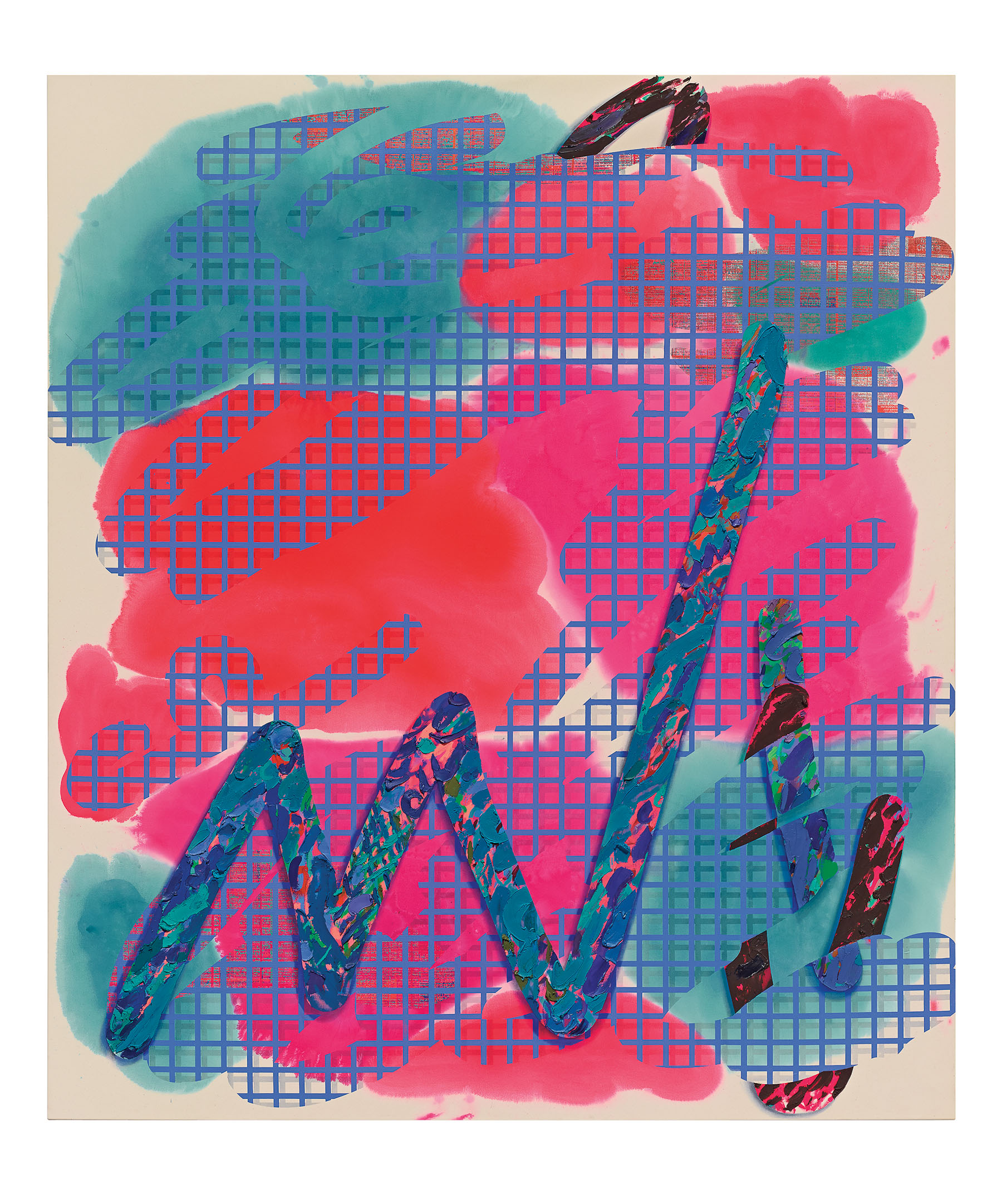

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2013. Flashe, acrylic, and oil on canvas; 137 !/2 × 120 inches. Photo by Fran and Doug Parker. Courtesy the artist, 356 South Mission Road, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

LO: That’s because I did this sort of burnished edge. Have you ever seen in old paintings that, when you take the frame off, they’re never painted up to the edges? And then you notice that it lends itself to a breaking of the frame of the picture? It came out of seeing a bunch of Impressionist paintings without the frames on. You see where a Matisse ended because he knew the frame was there. So there’s this little gap that makes the space of the painting even more foregrounded.

JT: There are those kinds of stretcher bars with a little curvature that gives you a soft edge where the picture can kind of fade off onto the wall.

SB: Like the edge of an old TV set.

JT: So you have these burnished, softened edges. And then putting the paintings so close together suggests that they are sequential panels of a narrative, a storyboard. And so you’re also suggesting that it’s not all in there, in the singular painting, but that it extends from one painting to the next.

LO: Yeah, but I’m hoping that, after you saw one, you wouldn’t think it was somehow incomplete, like it needed the other panels. I don’t know if it’s a conflict, but I just want to make the viewer aware that there is this tension. Like, you see through your periphery what’s on either side of you, and that’s also how you remember what’s behind you, and that’s an interesting thing about going to see a show that I wanted to exploit, that immersive or phenomenological thing. Just like it’s interesting to think about how to make everything happen inside the painting.

JT: You said “immersive,” and I was thinking, well, this singular thing that is painting when everything’s in it, that’s rather more absorptive, in the way Michael Fried talks about absorption. It’s the overall context that is immersive and the individual paintings are absorptive, right?

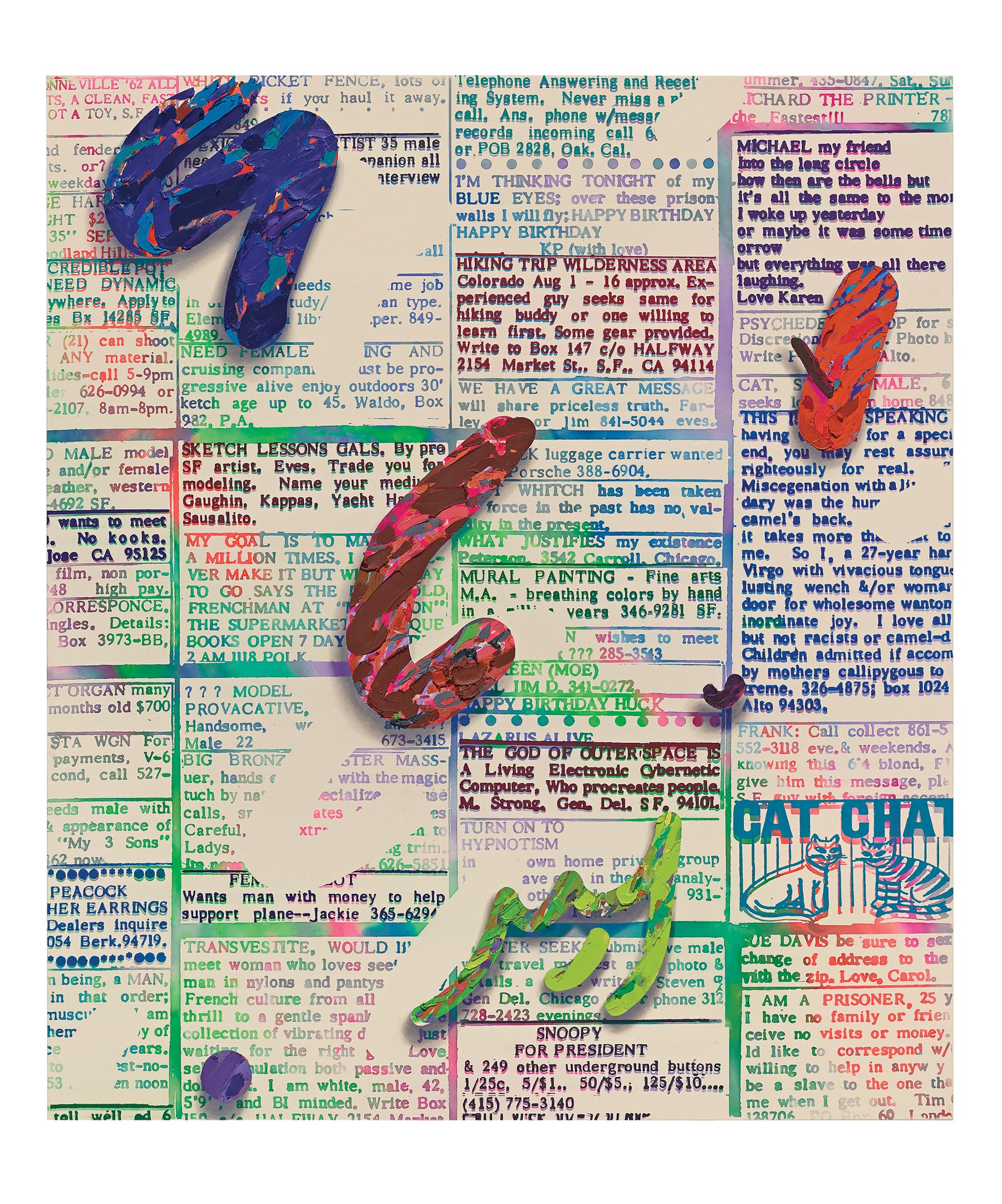

LO: That’s where I get unnerved, because I really want paintings to be problems and I want to activate the viewer to feel that this absorption is disrupted in some way. Even within the individual works, the reason I’m using these different techniques and have these drop shadows that are pushing out is so that you can’t fall into it like a window. The painting is coming out at you and asking you to put these things together. Why is this painted on a newspaper-like ground? Why is everything so disparate? It gives you more chances to level these hierarchies and talk about heterogeneity, because here’s a reference to Matisse and then a children’s mural, and you get to slam those two things together in the same exhibition, two different ways of making. So there are more spaces to move through, all these different levels in space.

When I think of absorption, I think of going into this world, this other world that relates to me more in a photographic way, where you’re teleported somewhere. Whereas what interests me in painting is that it comes out into the room, almost punches you in the face. And you can, if you want, go back in deep space because it has so much elasticity. But I really dislike paintings where I’m just meant to dive in. There’s a passivity to absorption that I’m not interested in.

JT: OK. But one can become completely fascinated by a painting, for whatever reasons, without paying any mind to what’s going on around it. It’s in the way the object addresses a viewer and controls their attention for a given period of time.

LO: Yeah, that’s about formalism, like the Hans Hoffmann school of painting, and what’s useful about that is it definitely teaches you the mechanics of how that actually works. There’s an objective truth to it that can be taught, and it has to do with certain thicknesses of line and certain angles and certain colors. Like, this type of square in this upper quadrant does this. I’m really interested in that, that it is actually factually true.

The paintings in the show use many of these techniques in many different ways. A gesture points to another gesture, but perhaps you are slowed down by the different ways the marks are made. Color is used strategically to move the eye and keep the viewer in the painting; it’s all very old school. But I guess what also interests me is how these formal devices get tripped up by contradictory forces, or used with more illustrative material that has a whole other agenda on how to look. So, the tail of a cat and the line that is a ball of yarn become abstraction, but at the same time, they remain this very pedestrian illustration.

I’m also interested in the meta-conversation happening formally between the paintings, so that in one instance, text refers to an actual newspaper, perhaps blown up large, and in another, the text is a texture on a textile, a sail. It then jumps over and calico-izes a cat,

or else the text is a stain and less illusionistic, just “painted,” all the while retaining its readability and referent. So all these devices move the viewer through the show in the same way he or she is moved through one of the paintings.

Installation view of 12 Paintings by Laura Owens, 346 South Mission Road, Los Angeles, January 2013. Photo by Fredrik Nielsen. Courtesy the artist, 356 South Mission Road, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

SB: So, what about still lifes? Do you think about still lifes in relationship to these paintings? Because the experience of looking at some of these works reminds me of my experience looking at 16th- or 17th-century still lifes. The way I look from there to there, the way my eye moves around the frame, it’s not the same as my experience of looking at abstract paintings.

LO: Well, on the desk where I was working the whole time there were only pictures of Cézanne still lifes. It’s just what was out, and that’s what I was looking at. And I thought that somehow that would make it into the work, but it didn’t happen.

SB: What I’m saying is that it did happen.

LO: Oh, cool.

JT: It’s true, it’s a very particular way of looking. With portraits you either focus on a face, or else you’ve got a figure-ground thing going on. With landscapes it’s more of an atmospheric thing; the gaze melts into space. You could be looking at an abstraction when you’re looking at a landscape. But pictures of things, which is what still lifes are, work differently: they make the eyes dance around from one point to another.

LO: I guess I’m just now trying to think about it, but it seems like there are more chances for the painter to be painterly in a still life painting than a landscape or portrait because you don’t necessarily have these predetermined ideas that relate to a recognizable reality in terms of, like, deep space and foreground and background relations.

JT: You also automatically have heterogeneity in the still life; it’s a bunch of different things sitting next to each other. In a landscape, everything is made to go together because it grew together, it’s organically fused in some way, and it’s basically the same for the figure. But here you’re given free rein.

LO: In a landscape, if there were an elephant next to a skyscraper, you’d think about it a little more. And if I painted the figure as abstractly as I think you can paint a still life, it would be a jarring idea about the psychology of the person. Whereas with a still life, there’s more room, more elbow room, to play with these elements and freely improvise. You can go from apple green to apple orange to apple purple, whatever, and it’s not like you suddenly get stopped because you see a purple apple, or because the apple’s sitting next to a deer hoof or next to a record. It’s just sort of seamless.

JT: Right. Because, as you’re saying with the portrait, if suddenly you’re devoting heightened attention to this part of the figure and not to this part, and you’re painting all the parts differently, that person will seem bonkers.

LO: Students end up working ten times too long on the face because they’re obsessed with getting it just right. Their brain won’t let go of it. We have this biological imperative. People get really caught up in painting the figure because, at an early age, you’re meant to recognize the face of the mother, immediately, so you don’t die probably. You respond to her face so she keeps feeding you or something. We have this recognition of faces and knowledge of proportions so that, if it’s off in a painting, you really notice it. Like, it’s really a bad painting.

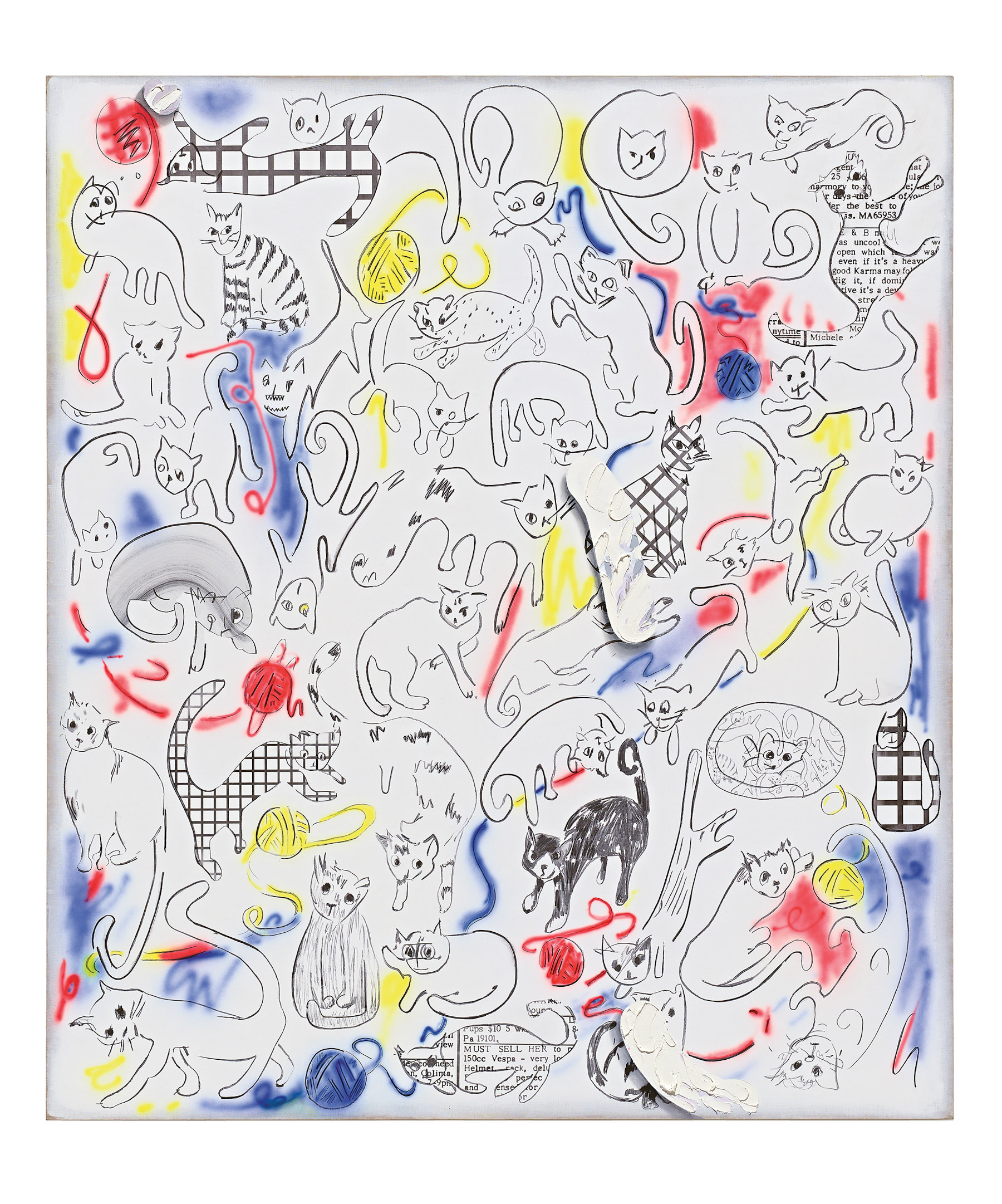

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2013. Charcoal, acrylic, and oil on canvas; 137 !/2 × 120 inches. Photo by Fran and Doug Parker. Courtesy the artist, 356 South Mission Road, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

JT: You see it even in old master portraits, where they can be very painterly, but then you’ve got the face. Everything around it begins to dissolve. The collar dissolves into the color of the painting or the jacket starts to fall away. Everything around the face becomes less and less specific.

SB: But that’s also about economics. Details take more time, and since people don’t care, you can get away with letting the fabric fade into the background. You can see that in some of Rembrandt’s portraits. However, there is this portrait of Jan Six, which Rembrandt gave the family as a gift because they were major collectors, and it still hangs in their house. What’s really strange about that painting is it is not really about the face, but the fabrics. It’s reminiscent of his late self-portraits that were painted years after this one. The collectors were not paying for it, so he painted exactly what he wanted.

JT: But I like what you were saying about the still life quality in Laura’s paintings, and I think you can say that about all of them. If they relate to any particular genre, it would be the still life. And so they can touch on these different themes: printing, childhood, Matisse, sexuality, flowers, sailboats, and so on.

LO: That’s amazing to me, because I definitely was putting that high on the list of what I thought the best painting would be, but I didn’t imagine I had any direct relation to the still life. I think there is a lot of play that can happen when you conceptualize a painting in terms of a still life, and what that means as a collection of objects, mundane or otherwise, that have materiality, texture, reference, etc. Maybe this is why, for many people invested in painting, Cezanne is still such an inspiration. He produces a brush stroke that is atomized, animated, maybe dissolving or appearing, and it is representative and indicative of the objects we look at in the painting. It takes a position that tries to represent the way looking actually happens, and how weird it is.

JT: That film critic and painter, Manny Farber, do you like his work? Because he’s also reproducing things that are themselves images already, so they become either a thing that’s in the painting or a hole in the painting, like you’re looking through it into another painting.

LO: Well, another thing I realized is that I really am invested in this idea of the painting within the painting. So the sails on the sailboat become their own paintings, or the classified ads I picked out become little poems. They become a kind of subject within the painting; each one becomes a little moment.

JT: It’s a subset of the still life, isn’t it, trompe-l’oeil painting? There you can have a bulletin board and then all these things pinned to it: pictures, letters, a scrap of fabric, maybe a feather. There’s some of that, too, in your paintings. There’s a lot of illusionistic trompe-l’oeil elements, and then there’s always some kind of grid structure that’s holding them together, that all these elements are hung on.

LO: Yeah, I think it all comes out of looking at this one Cézanne painting where there’s a lattice in the background that sort of fades into a still life. He also did this thing in a lot of the still lifes where the wallpaper or the curtains or something behind becomes part of the still life. A floral pattern merges with the actual flowers of the still life.

JT: So how do you decide when a painting is finished, or, as you said, where it ends?

LO: This is one of the most interesting ideas or questions one gets to work with when making a painting. And the answer is not there. I try to work against my own habits and conservative ideas to reformulate this as a question, but the opposite response of unfinished, no finish, not yet finished, can also lead to some habits and conventional thinking. I think this also gets close to ideas of taste in a nicely uncomfortable way, where you know you are almost a hack, clearly one step away from Thomas Kincade production, so what is keeping you from going all the way there? The illusion of speculative gestures? A search for some sort of infinite recontextualization that could carry the work forward? Are you a jam band that needs to stop jammin’? Does the drummer just stop? And then what happens? I try to just watch what is happening and throw shit at the fan.

SB: By doing that it also reflects your studio practice.

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2013. Flashe, acrylic, and oil on canvas; 137 !/2 × 120 inches. Photo by Fran and Doug Parker. Courtesy the artist, 356 South Mission Road, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

LO: Yeah, it’s always experiment, experiment, experiment, and nothing’s getting made. And there’s a sort of panic freak-out at the end. Like, there’s no paint on the actual canvas, Laura, what are you doing? It’s about letting it, the space and time for experimentation, happen as long as humanly possible before you really have to deliver. That’s really what happened for the opening, too: I was painting in here until the morning of the show, and everyone was… I mean, they weren’t ripping the paintbrushes out of my hand, but it was like, “Laura, don’t you think you want to go home and take a shower?” And then when everyone left, I was still moving stuff around, you know, putting paint away, putting the tables outside. It really was like I wanted to keep it open as long as possible—the painting, and the question of are the paintings finished. What’s finished?

JT: I’m thinking of that Francis Ford Coppola quote: “A film is never finished; it’s just left off.” He’s a case in point, right? He would probably want to keep making the same film throughout his career, and we’d just get these little dispatches from the set. If he could, he would never finish, and I think a lot of people feel that way about their production.

SB: Yeah, but I also believe that, if something works, the opposite has to work. So the opposite of that would be someone like Sol LeWitt, where the finish is decided, it’s predetermined, built into the proposal.

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2013. Charcoal, resin, and oil on canvas; 137 !/2 × 120 inches. Photo by Fran and Doug Parker. Courtesy the artist, 356 South Mission Road, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

LO: So then for him it’s more about committing to the proposal.

SB: Yeah, “the idea is the machine that makes the art,” right?

JT: Even there you could argue that the idea is the thing that’s never finished.

LO: And there’s also this potentiality that could be recreated with the directive that LeWitt has given them. As to when my work is finished, I’m hoping to leave it as a question mark for as long as possible.