Doonesbury © 2011 G. B. Trudeau. Reprinted with permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved.

The Stasi and the Smart Phone

In 1999, on the occasion of their appearance in the Venice Biennale, the Rumanian art collective subREAL (Cãlin Dan and Josef Király) made the trenchant assertion: “The history of the 1990s starts and ends under the sign of the archive. The archives compiled by the secret services of the Communist ‘block’ are one side of this reality. The corporate databases meant for monitoring potential customers are the other.”1

Yet despite the power and elegance of Dan and Király’s image of a decade neatly archived between the political oppression of collapsing state socialism on the one end and the commodity fetishism of resurgent global capital on the other, “the sign of the archive” in fact covers a much broader cultural terrain and is sunk much more deeply into the substrate of our history. Indeed, the archive’s theorization, explication, and invocation have made it a site of radical contest. Ultimately, the archive is implicated in our deepest understanding of modernist and post-modernist struggles, struggles both to instigate and to come to terms with the collapse of Enlightenment rationality and (ultimately) that of Renaissance humanism as well. If the sign of the archive necessarily entails the power to define and discipline our subjectivity, to eclipse our rationality and efface our humanity, it also and just as necessarily entails the potential articulation of knowledge and the possibility of interpretation, as well as the ability of Being to project itself as an oh so tenuous light shining against the darkness of the abyss.

Clearly, if the above characterization is anything close to accurate, any analysis on the scale envisioned here must be provisional and fragmentary at best. Nevertheless, it might be useful to begin by approaching the idea of the archive from a putative point of origination, and to survey the meaning thus exposed in its widest possible application. From there we can proceed to narrow our focus, hopefully in a way that will provide us with an “Ariadne’s thread” capable of guiding us at least some distance through the archive’s labyrinth.

The Mystic Writing Pad

That point of origination encompasses both a man, Sigmund Freud, and a text, his beguilingly metaphorical 1925 “Notiz über den ‘Wunderblock,’” or “A Note Upon the ‘Mystic Writing Pad.’”2 In that short text, which provides a kind of supplement to an argument developed in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Freud examines a pair of mnemonic problems that we have undoubtedly all experienced, namely: that our powers of recall are both fallible and impermanent. Likewise those external aids that, as of 1925, might have been deployed to enhance the retention of written information.3 “Thus an unlimited receptive capacity and a retention of permanent traces seem to be mutually exclusive properties in the apparatus which we use as substitutes for our memory: either the receptive surface must be renewed or the note must be destroyed.”4 Unless, of course, we take our notes upon the “miraculous” mystic writing pad, the operation of which Freud employs as a metaphorical and external model for the formation of the memory trace and the interaction between memory and consciousness. It works like this. The mystic writing pad, or “magic slate,” is a children’s toy where one writes with a stylus on a sheet of clear plastic laid over a wax tablet; the text vanishes when the plastic is lifted. Freud was pleased to note, however, that the traces of former mark making remained on the wax tablet, and thus was able to draw a distinction between the temporary inscriptions of perception and “permanent” inscriptions on the psyche.

Regardless of whether or to what extent one might be willing to accept Freud’s little “picture [of] the functioning of the perceptual apparatus of our mind”5 as usefully consonant with its actual functioning, his text sets out the theoretical parameters of what has become the wide-ranging, technologically complex, and ideologically charged discussion that we have described above. The mystic writing pad itself might have been a toy, but Freud’s desire to externalize memory as an unlimited system of permanent traces can easily evoke the wish for a totalizing combination of knowledge and power.

As a matter of convenience or definition, we can refer to such an externalized memory system, at the moment still having only a potential existence, as an “archive.” At least in theory, such an “archive” can contain an unlimited amount of information; and that information can be stored in an infinite variety of formats. Although we probably tend unreflectively to think of archives as comprising a certain class of easily “archivable” material (documents, photographs, film, sound recordings, and the like), the comprehensive Archive of an entire culture, to take an extreme example, would comprise all of that culture’s material artifacts in so far as those artifacts themselves comprised an external and collective cultural memory.6

Memory’s Junkyard

Clearly, however, the above definition is of little practical value. On the one hand, it has the kind of uncompromising perfection that we might attribute to a canvas covered with pure uninflected white pigment—a field carrying an unlimited potential for the articulation of meaning, but without any variation in that field to suggest a starting point or a direction for the unfolding of that articulation. On the other, we might just as easily substitute “black” for “white,” yielding now the image of a field in which all the articulating moves have already been played out, all the potential exhausted.

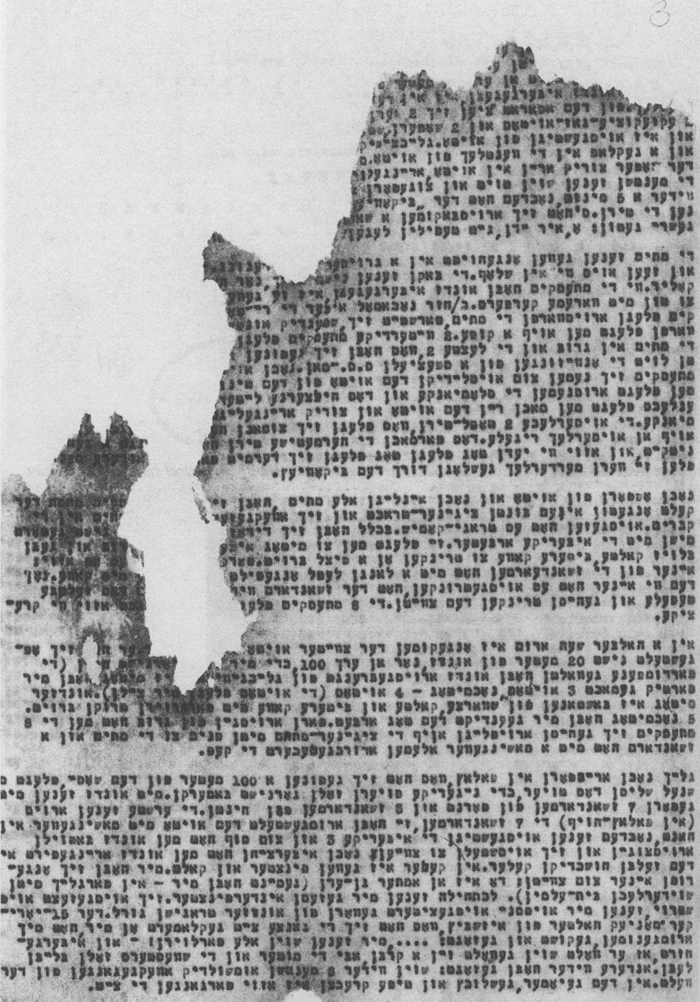

In point of fact, however, and despite the radical technological innovations to which I will return, the dream of a comprehensive external memory technology remains elusive; and the Archive itself thus appears as a site of fragmentation, erasure, and effacement. Indeed, I would argue that it must present such an image. In simplest form, we might see that image in a single page from the Oyneg Shabes (the “Joy of the Sabbath”), the archive assembled in the Warsaw Ghetto by Emanuel Ringelblum and his co-workers to document the progressive destruction of Eastern European Jewry from the fall of Warsaw in 1939 until the programmatic dissolution of the Ghetto in the apocalypse of the Final Solution.7 Alternatively, it might appear as a vast collection of texts, endlessly dense, sodden and decayed in some mnemonic junkyard or recycling center for dead memories.

The latter is precisely the image enshrined in Miles Coolidge’s monumental Backstop (2011) recently on view in his solo show at ACME. Gallery in Los Angeles.8 Measuring 92 x 181 inches, the picture is initially overwhelming in its juxtaposition of a glossy inkjet surface against the felt presence of a weighty and precariously balanced mass of printed material seen end on and filling virtually the entire frame. If knowledge indeed has an archaeology, then this photograph must surely render visible its geology: dense, sedimentary, deformed by tectonic forces, abraded and eroded by exposure to heat, cold, rain, wind, in constant process of slow, inexorable decomposition. Yet for all that it remains compellingly beautiful, with its strata of raggedy white, its friable vein of blue-shot yellow, and its striking splashes of blood red. What we see then is not just the slick surface of the print, but also the roughened surface of the “backstop” itself, the endlessly complex yet patterned system of superficial variations that suggest the unfolding of a narrative in deep time, a narrative hidden in the memory traces concealed within the sediments of text, yet even here in cross section guaranteed by its visible indices, each one a point of possible entry and a guarantor of potential interpretability. Thus, if one distressed and damaged page from the Oyneg Shabes can stand metonymically for the Archive as a whole, Coolidge’s Backstop can stand to it in a relation rather metaphorical or allegorical.

Miles Coolidge, Backstop, 2011. Pigment inkjet print, 91 X 181 in. Courtesy of the artist and ACME., Los Angeles.

Two points can be drawn from this comparison. First, that the fragmentary or degraded nature of the information presented to us under either of these images (Szlamek’s Chełmno testimony from the Oyneg Shabes or Coolidge’s Backstop) represents a real loss, albeit one that might be remediable at least in part through the reconstructive practices of history. Second, thinking back to our hypothetical canvases in black and white, that this very degradation (as Coolidge’s work in particular suggests through the richness of its apparently abraded surface) stands as a necessary precondition of the archive’s legibility, since it is precisely at those points of fracture or discontinuity that we can identify a site from which to begin our own project of interpretation.

It is perhaps open to question whether the term “archive” is best understood as comprising a structure, a technology, a body of information, or (as seems likely) a concatenation of all three. But insofar as we conceive it to refer to an object or process modeled by memory, it seems impossible that we should not also conceive its degradation or fragmentation as modeled by forgetting. And, since memory is necessarily personal, particular, individual and specific to the one that remembers and no other, what is forgotten is effectively gone, at least momentarily irretrievable, and in its place is now rather a fracture or a discontinuity.

True, only death, disease, and trauma can efface memory completely and forever. It might be argued that we have here reached the limit of the archive’s memory model, the point where the metaphor begins to show its own internal stresses and strains. Alternately, it could be that, even as forgetting, recollection creates in the archive fractures and fault lines that likewise provoke interpretation.

When such a feature is encountered in geology, it immediately begs the question, which, in its most rudimentary form, we might cast simply as: What happened there? likewise with that archival “geology” imaged in Coolidge’s Backstop, where the question “What happened there?” begins a process of interpretation that is rendered possible precisely by the flaw that the answer itself attempts to remediate. Unlike “real” geology, however, where there is in theory an answer to this question that is “objectively” correct (i.e. that corresponds to the actual unfolding of earth’s history), archival geology by its very nature as interpretation is always subject to contest—that is, to revisionist (re)interpretation. Likewise, every point of fracture, every line of discontinuity becomes a point of possible entry into the archive, and thus the staging point for a different interpretive process, the articulation of a different interpretation.

Nevertheless, the question of the “truth value” of particular archives can be a very serious issue, for example, in the case of subReal, those of the East German Stasi or the Rumanian Security Police. Indeed, one of the characteristic “historical” practices that we can associate with modern totalitarian regimes involves the systematic fictionalization of the archival record, which carries the implicit imprimatur of “objective” (and comprehensive) truth. Whether the construction of such an objective and comprehensive archive is a necessarily illusory goal, even as it remains an essential totalitarian fantasy, or whether its inherent and eventual fragmentation and degradation is the result of processes external to itself, is an issue that has been contested in blood, perhaps no more sharply than in the Warsaw Ghetto under Nazi occupation.

Memory and Counter-Memory

The almost unbelievable story of the efforts of the historian Ringelblum and a host of co-workers to document not just life in the newly-constituted Ghetto as it unfolded under the German boot, but also the effacement of Eastern European shtetl culture, and, eventually, the opening moves of the Final Solution and the doomed uprising of April 1943, is brilliantly told by Samuel D. Kassow in his 2007 study of the Oyneg Shabes Archive, Who Will Write Our History?9 As Kassow slowly and meticulously lays out the tale, it becomes increasingly evident that this question—Who will write?—is much more complicated than it appears at first. Among Ringelblum and his closest cohorts, the composition of the corps of archivists (the identity of Kassow’s “who”) was a matter of much dispute. Was their orientation to be secular or religious? Was their language of record to be Yiddish or Hebrew? Was their approach to be rigorously historical, or did journalism and even literature have a place? Exactly whose history was it that was being written? (This was an especially tricky question since the Ghetto itself was an artificial and externally imposed construct, its population heterogeneous in the extreme.) And exactly what events, or what kinds of events, constituted that history? All these questions and more were in play throughout the unfolding of the project, with answers changing both in response to the contingencies of events and continuing negotiation among a changing cast of actors. Yet it is clear from Ringelblum’s reiterated assertions that he expected himself and his fellow archivists to “rise above passion” and “maintain cool objectivity,” “no easy task,” he writes, “in times so tragic.”10

Indeed, the secular and life-long leftist Ringelblum describes his project, near the end of his life as he hides from the Nazis in the Aryan sector of Warsaw following the destruction of the Ghetto and the mass deportations to the death camps, in terms that are so movingly religious as to imbue his work with an almost sacred quality: “When a Jewish [scribe] sets out to copy the Torah, he must…take a ritual bath in order to purify himself from all uncleanliness and impurity. The scribe takes up his pen with a trembling heart, because the smallest mistake in transcription means the destruction of the whole work. It is with this feeling of fearfulness that I have begun…”11

Manuscript of Szlamek’s testimony about Chelmno in the Oyneg Shabes, Ringelblum Archive, courtesy Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. Reproduced in Samuel D. Kassow, Who Will Write Our History? Rediscovering A Hidden Archive from the Warsaw Ghetto (New York: Random/Vintage, 2007), Illustration between pages 283 and 285.

Ringelblum and his associates had not set out to transcribe a given text, but rather to inscribe a record of unfolding and contingent events. And although they never theorize the construction of the archive in just this way, the intense and meticulous discussions among the principal participants that Kassow records and analyses make it quite clear that they were deeply involved in all the myriad issues surrounding the desire to produce a “true” and “comprehensive” picture of their situation. This picture would, as they believed according to the optimism or the pessimism of the day, eventually be called upon to render one of two services. It would either provide a template for the recovery of a viable Jewish culture after the War (and indeed the outlines of that culture were also and not surprisingly much disputed within their circle), or it would provide a fitting testimony to the obliteration of a people whose absence would leave an irremediable lacuna in the structure of the cosmos. For, as the Ghetto poet Yitzhak Katzenelson suggested in one of his most poignant verses: “Without Jews, who would be left to comfort God?”12

What makes this episode exceptionally resonant for our present purposes (aside from the extraordinary affirmation of life in the face of abyssal darkness presented by the Oyneg Shabes archivists and their collaborators) is the fact that, even as their own time and their own narrative was drawing toward its inexorable close, the Nazis for their part were apparently intent on the production of a counter-narrative, an archival documentary cast in a quasi-verité style, which began filming in May 1942. Rather like the Oyneg Shabes Archive, which was buried for safe keeping, then entombed under the rubble of the Ghetto, and only (partially) unearthed in 1946, the Nazis’ raw footage was never cut and edited into a complete film, remained without a soundtrack, and was simply shelved—I suspect because the obliteration of the Ghetto made the project almost immediately redundant.

Recovered after the end of the War, the Nazi footage came to be accepted as an authentic source of information concerning conditions inside the Ghetto, its fragmentary state seeming precisely to have testified to its supposed authenticity. Although clearly produced in response to a fairly obvious, propagandistic motive to show that wealthy Ghetto Jews were content to lead lives of thoughtless self-indulgence while less fortunate Jews literally sickened and died on the streets, its conspicuous lack of narrative and soundtrack gave much of it a look of “raw” objectivity. Yet the Nazi footage in and of itself is difficult to evaluate; and the picture of Ghetto life that it presents, though obviously “false,” is arguably more complex than the original film’s planners may have intended. Some of it is clearly staged, crude (almost) to the point of caricature; but at other times it is poignant and finely nuanced, and at others, for example, when we watch the naked bodies of dead Jews sliding arms and legs akimbo down a wooden ramp into a common grave, undeniably and brutally powerful.

A Film Unfinished, directed by Yael Hersonski, 2010. Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories.

Even knowing what we know today, some of the sequences have a look of such stark immediacy that they evoke a communicative power of cinematic craft that transcends the obvious ideological frame of staged banquets and nightclub hijinks. It may indeed be possible to coerce the appearance of revelry, but the look of one who has stared into the face of death and sees its reflection in the camera lens is impossible to fake.

Eventually, a final cache of film was uncovered that made it absolutely clear that even some of the sequences that carry the most verité feel were carefully staged and often shot in a series of takes. The implications of this discovery for the archival status of the German footage, as well as the immediate impact of the filming on the inhabitants of the Ghetto, has been meticulously explored in Yael Hersonski’s stark and disturbing A Film Unfinished (2010).13 The raw footage is now contextualized by framing footage, voiceover, and the commentaries of both Ghetto survivors and Willy Wist, the only one of the German cameramen that it proved possible to trace.

No doubt, this has robbed the original footage of its once presumptive archival status (especially in comparison to the Oyneg Shabes) by exposing it as constructed rather than “externalized” memory. But that has not, or at least not in the same way, erased its value as an important historical document; and it raises as well a troubling question of the extent to which the difference between the categories “constructed” and “externalized” is really as definitive as we might presume or desire. Certainly for the German cameraman, the Nazi footage is the Ghetto archive. And as we watch Hersonski’s film we witness the playing out of a powerful drama of repressed memory (after the end of the War, Willy Wist abandoned cinema for a career as a scrap metal dealer) and forced recollection. One feels on the one hand that the Nazi project has rendered cinematography virtually a crime against humanity. On the other, we can see the work of Wist and his comrades as a forced testimony (and forced in a way never originally intended) to precisely the dehumanizing brutality that they transcribe in light and shade via the chemical emulsion on their film.

For the survivors as well, the experience of the film within the film is clearly complex, since they, undoubtedly more so than anyone else, are aware of all the fractures and discontinuities enshrined in its images—moved to tears both by the enormity of the truths and the falsehoods that it evokes in relation to the individual memories that comprise for each a personal, internal archive of suffering and death.

What is at stake here is clearly the fate of an archive much more encompassing than the personal system of mnemonic traces that for Freud could provide a record of the articulation of the individual psyche. As the authors of the Oyneg Shabes were well aware, theirs was a struggle to articulate and (if possible) preserve the cultural memory of Eastern European Jewry, even as that culture seemed to hang on the brink of a final and total obliteration. In one sense, theirs was a special case: the Nazi drive to erase the Jews of Europe except as a cultural “memory” constructed by themselves as an externalization of a willfully false and ideologically determined image is conventionally seen as without historical precedent or parallel, at least in the modern world. The holocaust is both a terminal and an originating event: the apocalyptic end of the tradition of Renaissance and Enlightenment humanism and the degree zero of a post-humanist world where “NEVER AGAIN!” has become a cry that echoes from Cambodia to Sarajevo to Rwanda and beyond, and “genocide” has become a term of art in international law.

Except that this may not be entirely or inevitably the case. As Emanuel Ringelblum wrote in his diary on June 26, 1942, as news about the Polish holocaust was being broadcast on the BBC: “maybe we’ll be saved after all.” For himself and most of his co-workers it was a vain hope. But perhaps not for the culture, the memory of which was externalized by the Oyneg Shabes. And perhaps not for the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

Ariadne’s Thread

Aby Warburg and Walter Benjamin are two names that have occurred with increasing frequency in the discussion of the way(s) in which the Archive mediates our relationship to the deep time of Western cultural memory itself. Warburg began serious work on his Mnemosyne (Memory) Atlas in Florence in 1928; it was cut short by his untimely passing the following year. Benjamin’s so-called Arcades Project was conceived in Paris in 1927; it was still incomplete at his tragic death in 1940. Both late and ultimately unfinished undertakings sought, among other things, to chart the Western cultural memory from its pagan roots in classical antiquity down through the constitution of modernism in nineteenth-century Paris.14 Benjamin’s “Short History of Photography” was a key document in the theorization of that technology in relation to archival practices.15 These two key cultural historians and critics have been linked more and more closely of late,16 and not simply for their complex interwar attitude that balanced a profound cultural and historical pessimism against at least a glimmer of hope for the future.

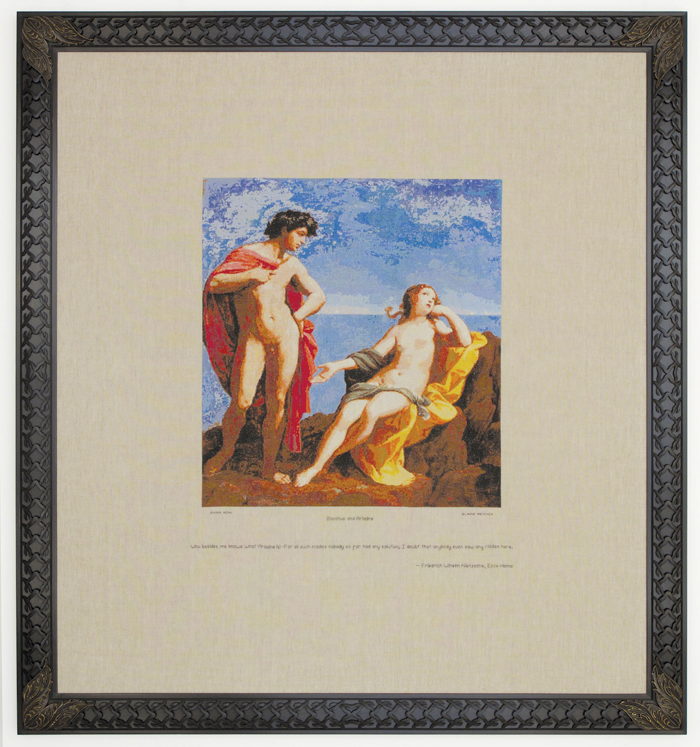

Neither these attitudinal complexities nor the equally complex outlines and intertwinings of their work can be addressed adequately here. But it is possible to explore, however briefly, the way in which Aby Warburg’s project has spawned a work that appropriates the archival impulse as part of an elegant pictorial and textual strategy juxtaposing the classical past, the Renaissance and Baroque rebirth of that past, and the modernist and post-modern critique of that reiterated cultural memory. In addition, this meditation on the density and lability of cultural memory is articulated within a productive practice that simultaneously celebrates the power of hand-work while acknowledging both the mechanical and the digital reproduction of that technique.

Elaine Reichek, Who Besides Me, 2010. Hand embroidery on linen in hand-carved frame, 57 1/2 X 53 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica, Ca.

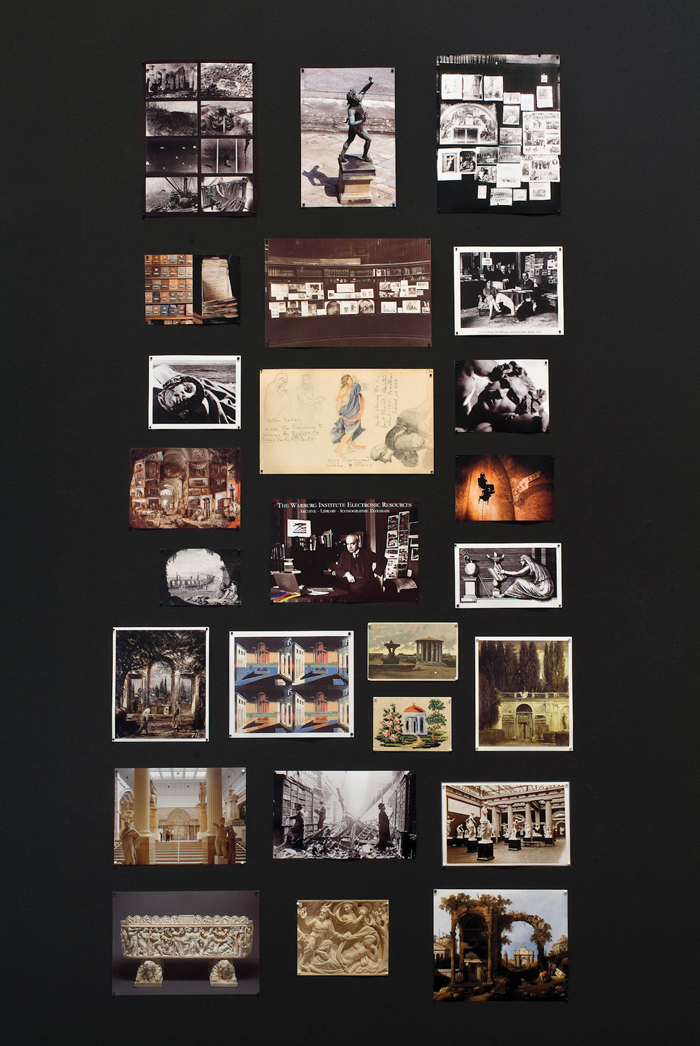

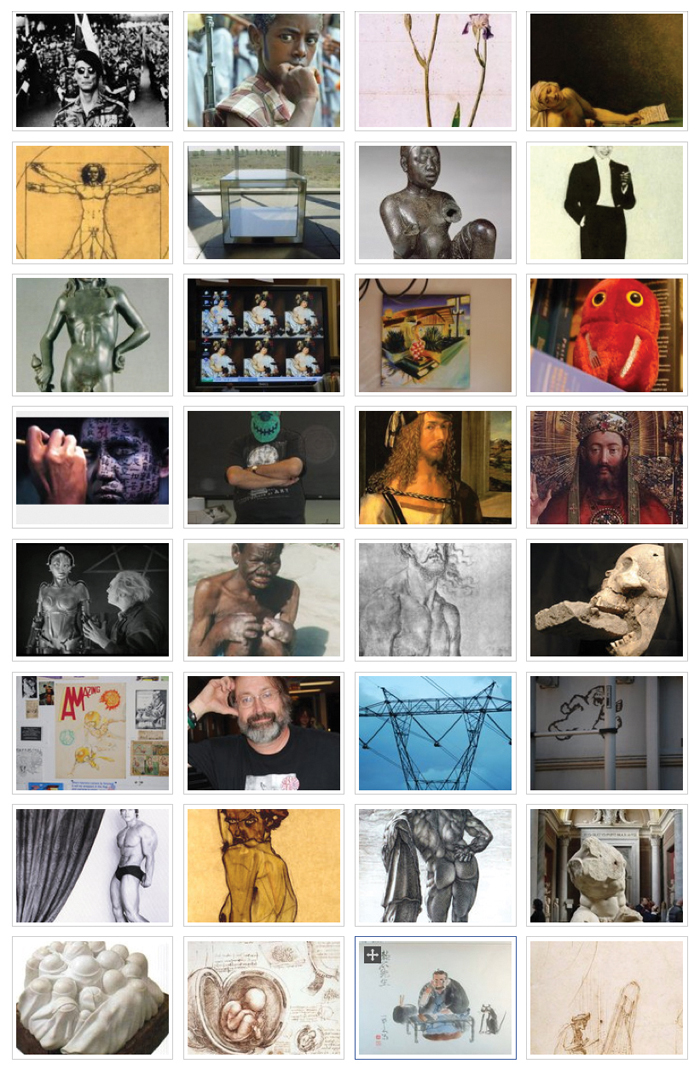

The artist in this case is Elaine Reichek, and the work is her ambitious Ariadne’s Thread (2008–11) recently on view at the Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Los Angeles.17 In briefest outline, the work consists of a series of (mostly) embroidered panels replicating (mostly) well-known works of art from Attica to Andy Warhol and centered on Titian’s magnificent Bacchus and Ariadne (1523–24). Each pictorial panel is embedded in a field on which is inscribed a gloss taken from the vast literature surrounding the Ariadne myth, beginning with a brief recapitulation of the story taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. These juxtapositions of image and text are then further contextualized by means of two huge black panels to which are affixed groups of related images that elaborate on the panels prepared by Warburg as the site for his Mnemosyne Atlas. In addition to the main elements of the myth, Warburg himself is explicitly acknowledged in a group of these images, as are the technological developments that drive the mechanization of embroidery.

The installation itself is enormously imposing, enclosing the viewer in a virtual museum of works dedicated to unraveling the story of Theseus, whose heroic dispatch of the monstrous minotaur was facilitated by his ability to follow the thread laid down by his soon-to-be-abandoned lover Ariadne, and so escape the coils of the labyrinth in which he and his fellow Athenian youths had been sacrificially imprisoned. And indeed, following the path from one text-image pair to the next is in its way not unlike following the path laid down by Ariadne herself, especially since the set of connections, resonances, and narrative and visual pathways suggested as one moves through the gallery is nothing if not labyrinthine in its complexity. Reichek presents the externalized traces of an image snaking across the landscape of an entire culture and penetrating from its nethermost depths (the deadly center of the labyrinth) to its uttermost heights (the heaven in which Ariadne herself is enshrined by her divine lover Apollo by whom, abandoned by Theseus on the island of Naxos, she is greeted in the installation’s central image).18

Elaine Reichek, Warburg Group, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica Ca.

We can easily see in Ariadne’s mythical thread the literal thread with which the artist embroiders her own story through the enactment of that practice that brings Ariadne’s story to “life.” At the same time, Ariadne’s thread, as it provides Theseus with his guide through the dangers of the labyrinth, is a figure both for the practice of interpretation (here bound inexorably to the practice of the artist) and for the practice of life itself. To quote, from the painter George Grosz, a simplified version of one of the texts that Reichek employs: “line is the thread of Ariadne, which leads us through the labyrinth of millions of natural objects. Without line we should be lost.” 19

Elaine Reichek, Pictures Archive, 2011, Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica Ca.

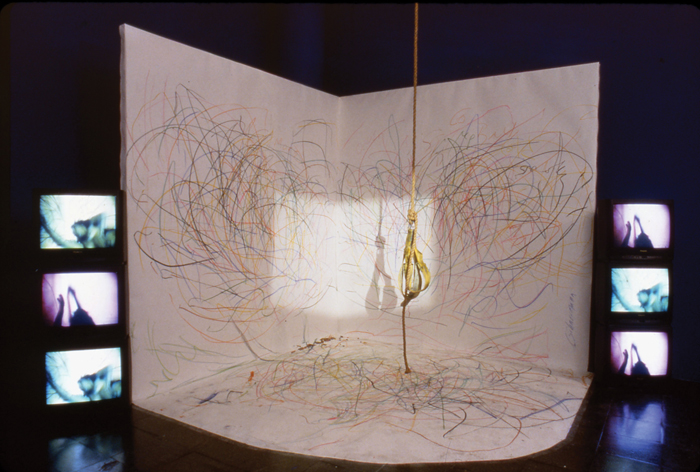

Having come now by a somewhat round-about route all the way from the written text of Freud’s memory trace, through the wordless trace of Ariadne’s thread, to the path’s material track through the world, we can pause to look at one final work that concentrates both on the track itself, the material trace that guides interpretation, and on the process of its making: Carolee Schneemann’s Up To And Including Her Limits (1973–76). This performance and its verbal and graphic residua have been given an incisive Derridean reading by Kristine Stiles in her book, Correspondence Course. On the graphic process involved in the performance itself, Stiles writes: “[Schneemann] envisioned her marks as a form of automatic writing, or trance drawing, something like a hypnotic tracking/tracing device that transcribed her physical sensations, movements and thoughts into words and images that mapped her artistic and physical processes in time. Still photographs of the performance show her body surrounded by texts and drawings, literally immersed in the two.”20 The graphic result, which Schneemann has described as “tracing…a trail [that] opens up a conducting path,” looks to me like a first draft of the Archive, which, Stiles argues, “offers an inchoate nonverbal image as an alternative to logocentric conditions of being and knowing, at the same time as it employs language to partner in decoding psychic interiority.”21

Schneemann has returned us via her performance to perhaps the most primitive staging of the Archive as a set of putatively inchoate marks that constitute the external traces of the psyche as it passes through time and space, that is, as its immediacy becomes memory. At the same time, those externalized traces, even in their least legible aspect, as we see them presented here, provide an image that reduplicates in anonymous form the thread of Ariadne, difficult to follow and yet our only sure guide through the labyrinth of the world and the maze of interpretation.

Carolee Schneemann, Up to and Including Her Limits, 1973–76. Installation: Crayon on paper, rope, harness, two-channel video on six monitors, super 8 film projection. © Carolee Schneemann.

Reichek, on the other hand, thematizes these concerns with extraordinary specificity, while situating herself at the site where the memory traces of Schneemann’s personal archive are reconfigured manually, mechanically, and digitally into a history of the deposition and transformation of a particular, seminal image that can stand metonymically for the deposition and transformation of the classical tradition that itself constitutes the Western culture memory.

Points of Entry

Every Facebook page an archive. Every status update a memory trace. Every mobile upload a point of semiotic origination. The Library of Congress an archive of archives of archives of archives…ad infinitum. As long ago as 1994, Jacques Derrida sensed trouble on the horizon, pondering in his inimitable way the counter-history of psychoanalysis had it unfolded at a time when e-mail existed, and noting along the way that “what is no longer archived in the same way is no longer lived in the same way.”22 And although this aphorism might at first seem but another paradoxical Derridean reversal of cause and effect, at some level, in some way, we must all sense that he is right. The explosive proliferation of archival technologies based on the digital coding and storage of information and embedded in our burgeoning social media, the “smart” (but not too smart) algorithms that drive our search engines, the hidden surveillance regimes imposed upon us by the very digital technologies on which we “depend,”23 and so on: all these things inevitably structure not simply how we remember, but what we remember, and even what there is to remember.

On the one hand, our virtually instantaneous access to all the information stored in so many archives may seem immensely liberating, not least as it facilitates a latent desire for a limitlessly expansive exercise in self-fashioning, at once occult and revelatory. My own Facebook page, for example, links to an album called “self-portraits,” which consists of an ever-growing grid of self-made and (mostly) “appropriated” images, each of which, at some particular point in time, seemed to me relevant in some way to my own sense of who I am (or was). Taken as a group, they form a semiotic identity puzzle, one which, needless to say, will never be “solved,” as it must surely be of interest only to me. Nevertheless, the structure of the grid (which can also be viewed as an infinite circular “narrative sequence”) demonstrates both the labyrinthine nature of the archive, which one can enter at any point but never perceive in its entirety, and a complex pattern of linkages between images, both latent and explicit, as well as the obvious fractures and discontinuities that suggest points of entry or stages from which to leverage an interpretation.

Glenn Harcourt, Self-Portraits (Fragment of a Facebook album), 2009–11.

Yet in a different sense, it can be seen as yet another Facebook-facilitated and empty exercise in the manipulation of information, an exercise of a type that fascinates even Zipper Harris’s slacker room-mate in Doonesbury.24 it is empty because information alone is distinct from meaning, and, in a world increasingly dominated by information technology, a world where the internet, the search engine, the social network, and the blogosphere have facilitated the illusion (or the fascist fantasy) of instantaneous access to a comprehensive archive that we ourselves contrive both to construct and manipulate, “meaning is irrelevant.”25

And this, of course, defines the darker “other hand,” opposed to the sense of liberation outlined immediately above. Even if the technology of the archive does not devour itself tail-first like the worm Ouroboros so that we fall into an eternal cycle of necessary re-archivization running ever faster simply not to lose ground (and, given the rate of technological innovation in the post-modern world, this seems a distinct possibility) we may soon awake to find ourselves stranded in an endless wasteland of information bereft of meaning.

There is after all no guarantee that this fate will not befall a culture that so often seems intent on projecting itself into a future beyond memory and history. Nor, however, is there any necessity that it must be so. Even if the path to that meaning laid down in the archive of personal, communal, and cultural memory is as slender as a thread, we can still follow it out of the labyrinth. If only we are willing to “[take up our] pen with a trembling heart.”

Glenn Harcourt received a PhD in the History of Art from the University of California, Berkeley. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles.