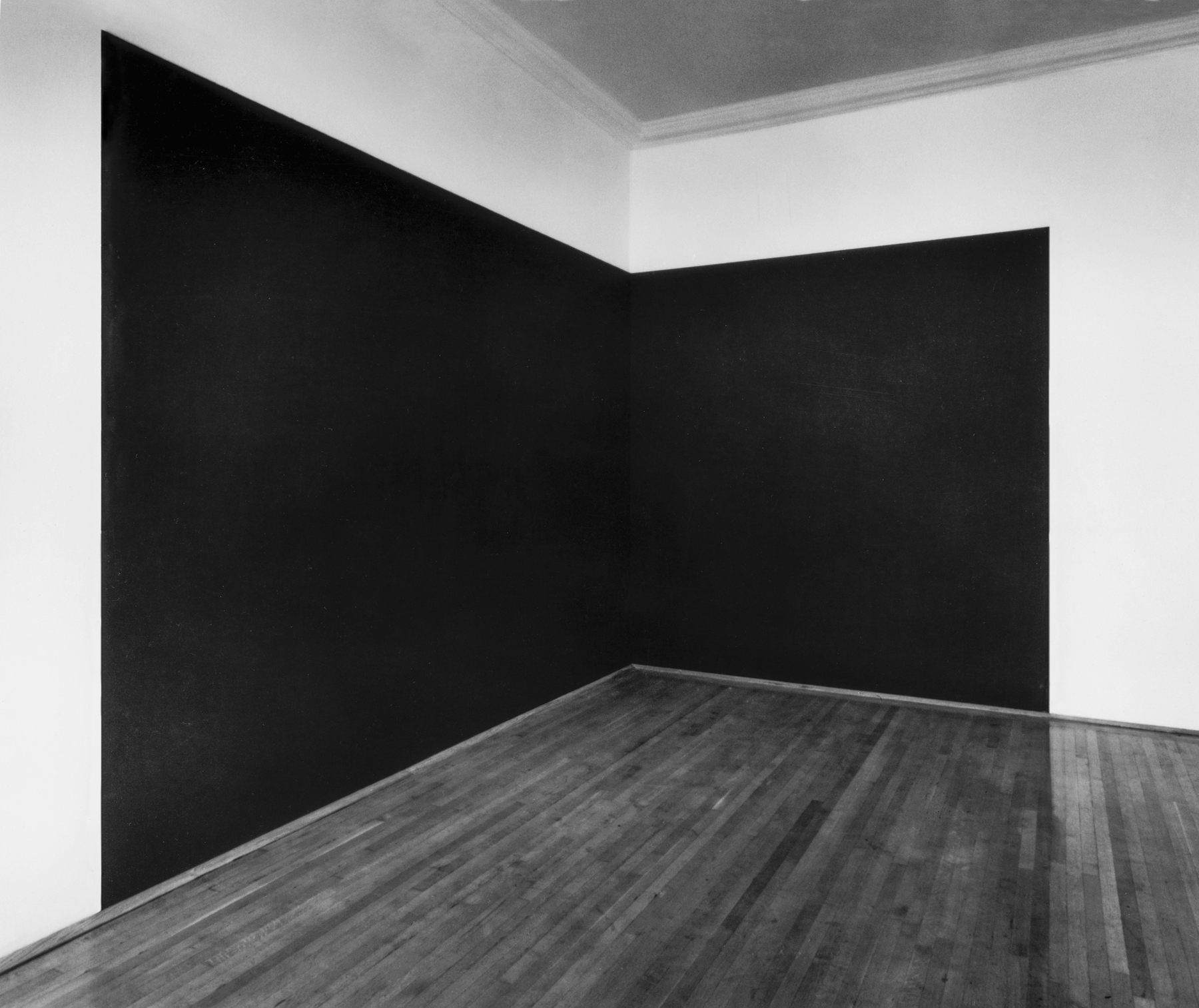

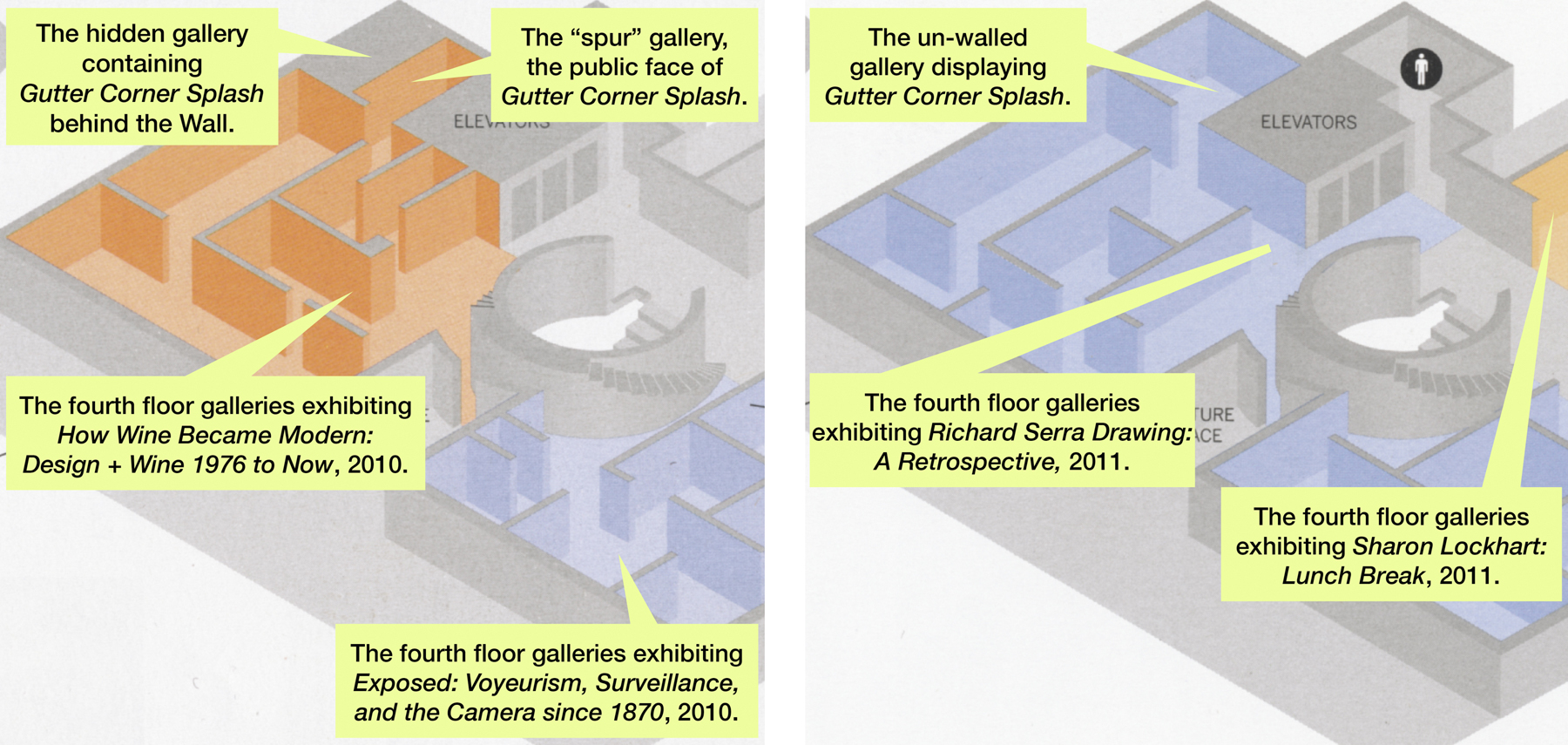

Once upon a time, on the fourth floor of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, there was a tiny spur of a gallery, a fifteen-by-nine-foot cul de sac that jutted out from the flow of larger galleries. It was the sort of space that visitors might overlook as they follow the main arc of an exhibition, a space whose former residents might have included the 2009 exhibition of Glenn Ligon’s self-as-runaway-slave posters, ephemera from the 2008 Frida Kahlo show, and Gerhard Richter’s airplane paintings from his 2002 retrospective. My inability to precisely reconstruct the gallery’s roster arises not so much from the passage of time but from the deception that the spur perpetrated. This grifting gallery proposed itself as only half the gallery that it truly was. Its other half? A pea palmed in a shell game. I was an easy mark. It was not until SFMOMA’s 75th anniversary retrospective, in 2010, that I realized that one wall of the spur gallery was temporary, even though I had seen its conjoined twin years before. Sealed up behind the wall, and reposing in silence if not patience, was Richard Serra’s Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift (1969/1995). Each time the wall came down, the sculpture’s eight lengths of cast lead overtook the spur gallery. Because one of the lengths remained adhered to the gallery wall and the others weighed a ton apiece, the sculpture declared, and still declares, its immovability and permanence.

Museums rotate artworks from their permanent collections into and out of their galleries all the time, but few of these works, if any, claim their exhibition space even when they are not on view. In this way, Gutter Corner Splash ’s double life has been unique, but this has not protected it from change. Following SFMOMA’s enormous two-year expansion, the containing wall has come down forever. Although the galleries on the fourth floor of the “old” Mario Botta-designed building will be devoted to temporary exhibitions, Gutter Corner Splash , along with several Serra works from the Fisher Collection, will be permanently displayed.1 But that’s only half the story.

The shell game was all the more impressive because it preyed upon the ways in which museums both allocate space and construct and sustain their art historical missions through the narrative of exhibition. Gutter Corner Splash, in collaboration with its wall, had been an object lesson in seeing, a disruption of the apparently smooth space-time continuum of “history.” In 1940, German philosopher Walter Benjamin defined history as the story told by the victor, a story that preempts from the historical record the account that the vanquished would give.2 It is a testament to the power of this concept of history making that some of us could be surprised upon seeing Gutter Corner Splash each of the handful of times that the museum revealed it over the past 20 years. It is equally a testament to the power of imagination that, for the duration of each exhibition in which it was displayed, we would gracefully reintegrate its forgotten moment into the present. Yet, prior to its permanent display, Gutter Corner Splash, with its wall, had narrated an alternative art history. This history was one in which the past repeated and the vanquished spoke, perhaps in the voice of another Benjaminian notion: the “dialectical image.” In Benjamin’s revelatory moment, during which, as he said, “what has been comes together in a flash with the now,”3 the sculpture appeared as both past and present, vanquished and victorious, hidden and manifest, and the museum uncovered its narrative and curatorial process, exposing it not to ridicule but to inquiry.

The Perpetual Motion Machine

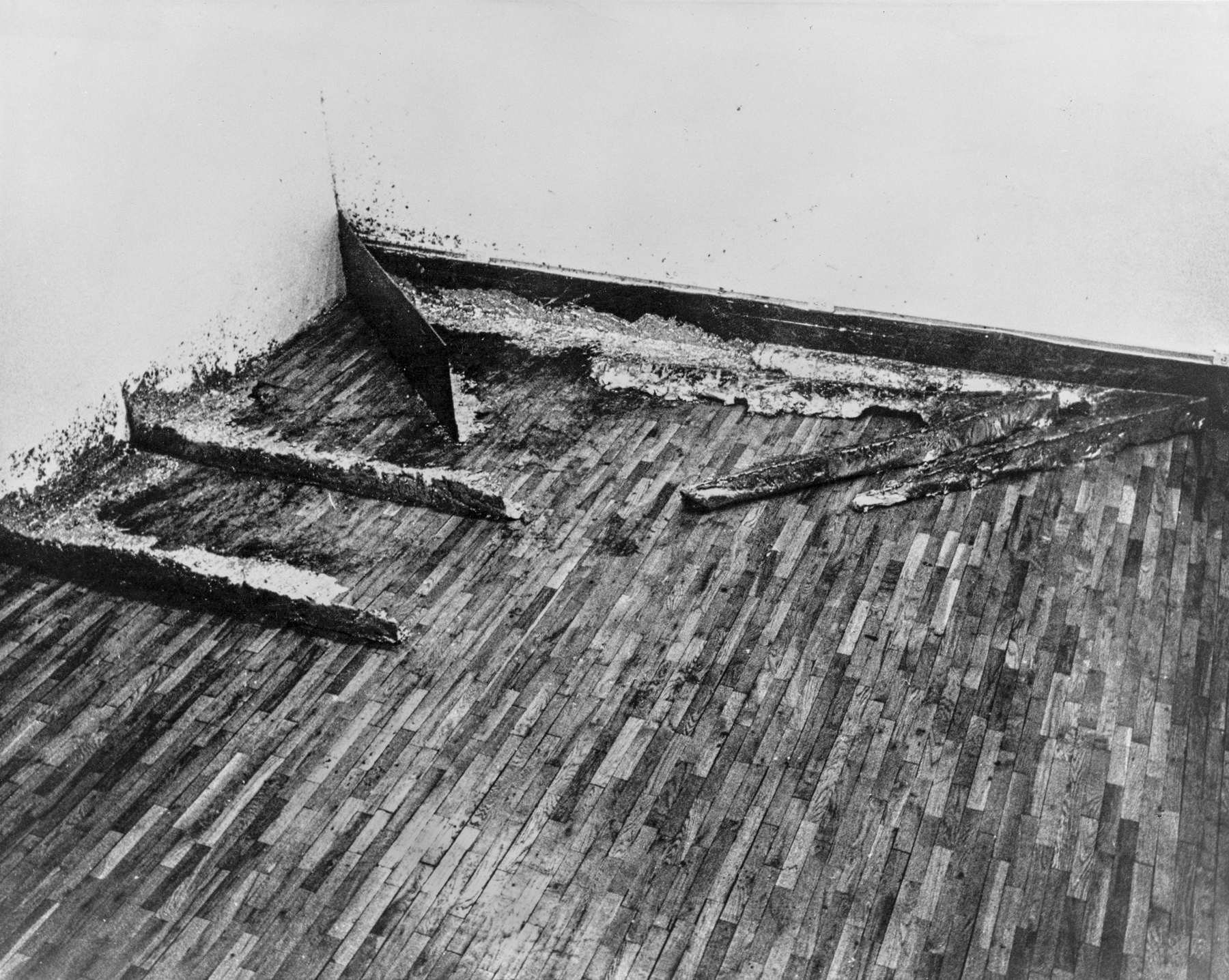

Imagine Serra, aided by a merry band, splashing molten metal into the “gutter”—the juncture where the gallery’s back wall meets its floor. Over the course of three days, the team exhausts a supply of more than 15 thousand pounds of lead in order to materialize eight castings. They remove seven from the parent corner-mold, invert each, and place each side-by-side with its siblings. The eighth they leave attached to the wall. Stretching nine feet into the space, Gutter Corner Splash extends like an industrial park of warehouse rooftops or an inlet roiled with surf. No matter what it evokes, the sculpture eloquently records the process of its construction and renders in metal the structure of the gallery.

The “spur” gallery of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art during the exhibition How Wine Became Modern (November 2010 – April 2011). Photo: Saul Rosenfield © 2010. Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In a video SFMOMA filmed during the sculpture’s installation, Serra explains that he added the phrase Night Shift to the title to reflect the accommodation he and the museum made to protect daytime crowds from the toxicity of the lead fumes.4 This concealment of the primal moment of conception prefigures the lifetime of seeming ambivalence the sculpture has endured, all the subsequent covering up, as if to shield the world from the creative act itself. During the SFMOMA retrospective, Gutter Corner Splash interacted with visitors like a lunatic otherwise sequestered in the attic and allowed to join the party only long enough to appear to prove eccentric rather than dangerous. But the sculpture is dangerous—and not only because it is made of lead.

Upon encountering the sculpture, my first impulse is to breach its border. The desire to enter any sculpture’s “personal space” may, in fact, be essential to the definition of the sculptural medium, the necessary realization of my four-dimensional relationship with the work. Perhaps, in fact, no sculpture that is protected by museum stanchions or guards or convention is ever truly experienced. Serra’s more recent works resolve the oxymoron of “museum sculpture” by incorporating the breach, through pathways imposed by enormous weathering steel panels, into acceptable exhibition behavior. Gutter Corner Splash does not. An invisible line several inches before its leading edge echoes the lines of lead that follow and defines, without the guard’s intervention, the point past which visitors intuit that they may not venture. But Serra has found, whether wittingly or not, a solution: the piece itself does the breaching. It advances toward me.

Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift, revealed, its restraining wall torn down during SFMOMA’s 75th anniversary retrospective in 2010. Photo: Saul Rosenfield © 2010. Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Studio of Richard Serra.

Standing in the gallery, as if on a beach, I might almost believe that these molten waves would fail to honor the laws of motion and would continue coming, overtaking first the room and then the museum. So it is no surprise that my second intuition is to flee. I did not need to construct the metaphor of incoming surf to feel the advance of the castings. They force themselves upon me. Serra calls “space”—not lead or steel—his medium.5 Gutter Corner Splash is not a static arrangement of metal corners but a perpetual motion machine, a work that shows not only the artist’s process of shaping—splashing, casting, removal, and duplication—but also the continual repetition of that act. In this experience of breaching—this illusion of motion, like the disorientation I feel as I watch my sandy feet through an overlapping surf—Gutter Corner Splash is the actor defining its space. If, throughout my account, it sounds strange to invest the sculpture with agency, and to frame the relationship between museum and sculpture as reciprocal, for the moment consider that the objects that we possess also possess us.

In his splash pieces, Serra saw a different sort of danger. Although these works successfully violated the sculptural conventions of the pedestal art that Serra sought to challenge, the artist feared that “the lateral spread of materials, elements on the floor in the visual field,” would fail to subvert “the pictorial convention,”6 which he also sought to undermine. He worried that an active sculptural participant would become a passive, immobile viewer, scanning a flattened artwork from outside instead of breaching its boundaries. Or, as Lynne Cooke put it, Serra was concerned that the floor would become a “two-dimensional planar support for what was read as a graphic incision.” 7 Time would stand still; space would become static.

Richard Serra, Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift, 1969/1996. Cast lead, 19 x 108 x 179 inches. Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Jasper Johns. Photo: Saul Rosenfield © 2010. Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Studio of Richard Serra.

It is true that I cannot walk around or into Gutter Corner Splash, true that it submits itself to the inertia of its “planar support,” and true that, from above, it might appear “pictorial.” But Serra’s reassessment of his “lateral” artworks seems to underestimate both their capacity to induce a feeling of motion and their influence on their sites. Encountering the un-walled version of the spur gallery, I feel the space tilting toward the sculpture, succumbing to its weight. The sculpture’s spread of metal not only joins the otherwise distinct surfaces of plasterboard wall and wooden floor, plating them in lead; it also puckers and roils their smoothness in an upheaval of right-angulation.

So the lead corners do reconfigure the gallery’s space—perhaps not as profoundly as Serra’s weathering steel sculptures—but in ways that are at least as effective as the artist’s black paintstick drawings. This is significant because Serra saw in the materiality of the drawings their capacity to interact with the space of the gallery in which each drawing hangs. Like sculpture, Serra said, the drawings “alter the perception of the volume of a space, [but] they also reassert its structural principles and physical identity, in that they call attention to the architecture’s boundaries and edges.”8 Serra chose black paintstick for two reasons: its light-absorbing qualities and its relative resistance to metaphorical association when compared to other colors.9 It turns out that it’s not primarily the metaphorical associations of wave, rooftop, warehouse, and barrack that engage me. Instead, it’s the material fact of the gutters that marshals the space and turns it around. The heavy, grainy, flakey, sludgy materiality of lead; the silver-grayness of its surface; the dull-sharpness of its right-angled corners; the stickiness of the formerly molten metal to which still adhere bits of the gallery’s wall; the repetition of right angle after right angle: all conspire to warp the space and, as much as any accidental resemblance, draw me into the sculpture’s zone of influence. Likewise, it is not just the lateral spread of this material that charges the space. The gutters highlight, unmetaphorically, the key structural component that transforms continuous planes into enclosure. When revealed, Gutter Corner Splash tells it like it is, narrating the three-walled space in the language of the eight gutters. The sculpture becomes a meditation on rooms as spaces—in a space that refuses to remain stable as a room.

The Resident Nomad

Gutter Corner Splash exemplifies a defining characteristic of much of Serra’s sculptural work: site specificity or, more broadly, site sensitivity. So insistent is the sculpture in its specificity—it literally adheres to the gallery, and removing the back gutter would destroy the wall—that the museum has continued to demolish and rebuild its restraining wall, working around the piece—or rather, with it—to expose or block access.

The poetry of the museum’s cycle of wall building and demolition lies in its unrelenting reversal of the fate of what is arguably Serra’s most famous piece, Tilted Arc (1981–89), which bisected lower Manhattan’s Federal Plaza. That sculpture’s short and controversial life (during which it was accused of obstruction, danger, and ugliness) is one of the signature events of the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s. Of Tilted Arc, Serra proclaimed, “To remove the work is to destroy the work.”10 This assertion of site-specificity explains both the fact that Tilted Arc’s date must now be expressed as a lifespan, and that Gutter Corner Splash has two birthdates, 1969 and 1995, reflecting the sculpture’s original incarnation in Jasper Johns’s New York studio and its resurrection in San Francisco. Ironically, if Tilted Arc was destroyed, at least in part, because it was derided as a “wall,” Gutter Corner Splash survives because its wall, rather than its substance, is continually destroyed. Gutter Corner Splash, it could be said, lives the long life that Tilted Arc also should have enjoyed.

Richard Serra, Pacific Judson Murphy, 1978. Installation view. Pacific Judson Murphy was displayed during Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective(2011), which was co-organized by and exhibited by San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Menil Collection, Houston. Photo undated and unattributed. Courtesy Studio of Richard Serra.

Johns donated what was then called Splash Piece: Casting to SFMOMA in 1991. Serra re-executed it in 1995, the year the museum completed its then new building. Unlike Tilted Arc, whose destruction was a communal and political act, Splash Piece’s destruction was a private one, necessitated by the sale of Johns’s studio building. The decision to recreate the artwork in SFMOMA was collaborative, involving Johns, Serra, and SFMOMA’s then director John Lane, who “all agreed that this would be a wonderful solution for the work.”11

Art historian Miwon Kwon cites Gutter Corner Splash in her critique of “refabrications,” which she defines as reconstructions during the 1990s of “vanguard” and “radical” artworks of the 1960s and 1970s. Refabrication, Kwon says, “unhinged” site-specific works from their specified sites, mobilizing them as portable, and therefore commodifiable, pawns of galleries and museums. Kwon quotes Susan Hapgood’s 1990 essay, “Remaking Art History”: “The once-popular term ‘site-specific’ has come to mean ‘movable under the right circumstances.’” Kwon concludes that the practice of refabrication “shatter[s] the dictum that ‘to remove the work is to destroy the work.’”12 But Gutter Corner Splash manages to avoid the pitfalls of mobilization and exploitation for several reasons. Tilted Arc’s site specificity depended on a unique space, Federal Plaza and its surrounding buildings, to engage in a sculptural dialogue about ideas of power, government, and architecture. Splash Piece/Gutter Corner Splash proved, through its transformation, that although it was equally site specific, the situation it required was not unique.

Richard Serra, Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift (detail), 1969/1995. Photo: Saul Rosenfield © 2010. Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Studio of Richard Serra.

Gutter Corner Splash is the same work as Splash Piece, since Johns “donated” Splash Piece’s concept, process, and material. Yet Gutter Corner Splash is also not the same piece, since the site-specific objects produced by portable concepts, processes, and materials are not, themselves, portable: both the site of Serra’s effort, which impelled his process, and Serra’s thinking, the source of the concept, were different in Johns’s New York studio, in 1969, than they were in SFMOMA, in 1995. In fact, Serra specifically rejects the procedure of Conceptual art’s progenitor, Sol LeWitt, who created a set of written instructions for others to faithfully transpose and execute in new spaces. “For me,” Serra says, “the conceptual framework that LeWitt laid down was overly scripted.”13 Unlike the draftspeople/re-creators seeking fidelity to LeWitt’s instructions, Serra takes his cue from the space itself. The result is not so much a re-creation as a co-creation, a collaboration with the space rather than an imposition on it. Indeed, during its evolution, Splash Piece acquired not only a new site and an additional 12 thousand pounds of lead, as Serra’s vision outgrew the three thousand Johns had donated from Splash Piece, but also a new title, to mark Serra’s dialogue with the expanded space. “It didn’t seem to make sense to do that piece [Splash Piece] in this large space,” Serra says in a second SFMOMA-produced video, in which the artist discusses his lead splash pieces in general.14

In fact, Splash Piece bears little resemblance to Gutter Corner Splash. In the earlier work, lead traces the gutter along the 15-foot back wall of the Johns space. At the gutter’s left end, a 19-inch-high solid lead plate, about five feet long, bisects the corner of the room; splashed lead forms a corner at the gutter between it and the floor. At the right end of back-wall gutter splash, two parallel gutter casts, each about seven or eight feet long, bisect the right-hand corner of the room. Together, the elements form an unfinished triangle: one side is the standing lead plate, the second side is the two gutter castings, and the base is the splashed back wall. There is no apex to this triangle. Instead, in front of the lead wall formed by the vertical plate, two more castings, each about six feet long, jut out into the room at right angles to the left-hand wall. Unlike Gutter Corner Splash’s associations with waves or roofs, it is the geometry of Splash Piece that redefines the space of the room. In any case, if the viewer did not know that Gutter Corner Splash was the reincarnation of Splash Piece, there is little in the physical configuration or photographic experience (we have only a photograph of Splash Piece to judge) to signal their common origin. As Serra explains, “There’s something about trying to remake something you’ve made before which never makes sense anyway. And that’s never usually what happens: even if you try to do it, you invariably make something else.”15

But Kwon’s critique of refabrication is broader than this. She suggests that, by unhinging what had been site-specific art, galleries, museums, and artists undermine the radical nature of site specificity, the goal of which had been to undercut the autonomy of the artist and the artwork, to force each to yield to the authority of the site. It is true that, on display, Gutter Corner Splash easily reverts to autonomous “artwork,” rather than radical “intervention.” However, by co-opting and collaborating with the very wall the museum had used to control it, the sculpture diverged from other post-1960s refabrications. It refused to remain docile, to stay in its place, instead enacting an ephemeral yet ongoing performance of display and disguise. Gutter Corner Splash evolved from “phenomenological,” the first of Kwon’s three categories of site specificity, to the third: “discursive” or “nomadic.”16 It became as akin to performance art and internet-based art as it was to the unhinged “autonomous” sculpture. The resulting joint agency between SFMOMA and Gutter Corner Splash might have been imperfect for both parties, but the wall-building compromise delivered rewards to each. The museum’s reward was not only flexibility but also a narrative loosened by the sculpture/wall collaboration’s unconventional voice, media, and shifts in time. The sculpture’s triumph was to be both immovable and nomadic at the same time.

In this way, the Gutter Corner Splash/wall collaboration had shared as much with its less adaptable cousin, Tilted Arc, as it had with its former self, Splash Piece. Of Tilted Arc, art historian Douglas Crimp made the following controversial observation, in 1986: “Serra once again used sculpture to hold its site hostage, to insist upon the necessity of art to fulfill its own functions rather than those relegated to it by its governing institutions and discourses.”17 Gutter Corner Splash, guilty as Tilted Arc was charged, had held hostage time as well as site, refusing to remove itself to accommodate the museum’s exhibition calendar. Each of these hostage takings was an eloquent if quixotic gesture toward the ambition of stasis. Crimp concluded that Tilted Arc revealed “the true specificity of the site, which is always a political specificity.” It’s our feelings about what Tilted Arc had been in the specific space of Federal Plaza—including the sculpture’s site-disturbing nature and the controversy surrounding the work—that made the sculptural intervention exactly what it was. Relocating it, as the United States General Services Administration (GSA) had proposed, would have made Tilted Arc something else entirely.

Richard Serra, Splash Piece: Casting, 1969-1970. Lead, 19 x 108 x 179 inches. Executed and installed in Jasper John’s studio, New York. Photo: Gianfranco Gorgoni. Courtesy Gianfranco Gorgoni and Studio of Richard Serra.

In a June 1989 New York Times article, GSA regional administrator William J. Diamond proclaimed, “It’s a revolution in our thinking—that open space is an art form in itself that should be treated with the same respect that other art forms are.”18 Diamond’s doublespeak attempted to conceal the botched Tilted Arc process, which, however you feel about the sculpture, contradicted the GSA’s own guidelines for commissioning public art.19 It seems no surprise that Tilted Arc’s history continues to haunt the plaza. In the spring of 2013, the GSA replaced Martha Schwartz’s snaking bright green benches, which followed Diamond’s post-Tilted Arc “open space,” with Michael Van Valkenburgh’s patchwork of plantings. But instead of repeatedly erasing the past, the GSA could have championed Titled Arc and used the past thirty-five years to write a more complex history of the plaza. Had it invited a layering of interventions to coexist and converse with each iteration of the space, the GSA would have extended Serra’s transformation of the plaza and manifested the truest political specificity: the exchange of ideas.20

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc,1981. Weatherproof steel, cylindrical section; 144 x 1440 inches along the chord x 2 1/2 inches thick. Photo Anne Chauvet. Courtesy Studio of Richard Serra.

The Obstinate Orphan

Gutter Corner Splash succeeded where Tilted Arc was forced to fail. Behind the spur gallery wall, the sculpture prevailed, defying even the construct of “museum.” Within this construct—a space that houses artifacts (art, nature, technology, history, etc.) to illustrate the story that is at the heart of the museum’s mission—almost any artifact is replaceable because other examples, even of iconic works, can usually be found. In fact, they ought to be found, which explains why hundreds of museums rely on similar artworks to tell similar stories. Finding these artifacts, the museum demonstrates the widest applicability and, therefore, the fundamental “truth,” of its storyline. Artifacts that fail this test risk dismissal as subjective, accidental, or digressive.21 If the pre-museum-expansion Gutter Corner Splash had been like any other artwork, it would have fallen into one of two museum categories: permanent, if not iconic, and always on the display; or warehoused, removed from the exhibition floor until a curator calls it into action to illustrate the premise underlying a specific exhibition. But it had not been like any other work: it refused to relinquish its exhibition space even when it was in storage, claiming the status of both permanent and stored, thus forcing the museum both to give up that space and to build the wall.

Other museums have revealed the partiality of their story-telling process by temporarily exhibiting warehoused art as warehoused art, revealing the porous boundary between the two museum categories. But Gutter Corner Splash had made enduring what, for example, the Oakland Museum of California achieved for only six months. In 2010, OMCA welcomed artist Mark Dion to juxtapose “orphaned” objects from the museum’s stored collections of nature, history, and art—in effect, the museum’s archive of its former narratives—with objects on exhibit in its galleries, the transcript of its current narrative.22 So Admiral Peary’s 1906 Arctic expedition sledge, lent by the New York Museum of Natural History 75 years before and never accepted back by its original owner, suddenly appeared next to William T. Wiley’s rope-and-wood construction, How to Chart Course (1971). A stuffed baby giraffe sidled up to Rupert Schmid’s 1895 white marble nude, California Venus; a Micronesian Yap stone coin, two feet in diameter, was deposited in a gallery of Gold Rush art; and a five-foot-tall ceramic electrical insulator dwarfed a vitrine of pottery vases.23 By fostering the Oakland Museum’s orphans, reintroducing them to society, Dion disturbed the idea of a stable narrative. But since the orphans’ reprieve was temporary, the preexisting narrative reasserted itself after the objects were reinstitutionalized.

The Marvelous Museum: Orphans, Curiosities & Treasures: A Mark Dion Project (2010-11). Installation view, Oakland Museum of California. Photo: Saul Rosenfield. © 2010.

By commandeering premium exhibition space, Gutter Corner Splash refused the status of orphan, insisting instead on a hybrid status of being simultaneously in society and in retreat, exhibited in its warehouse and warehoused within other exhibits. It seems likely that the museum, if it could have, would have removed the sculpture to storage when it was not on display. Building and re-building the wall took effort, a process made more complicated by the need to protect the sculpture during construction and demolition. Had the museum left Gutter Corner Splash on view all the time, however, its presence would have interrupted the narrative flow of the fourth floor galleries, which, as it happens, often hosted what were among the museum’s biggest and most publicized exhibitions. And, since the unveiled sculpture dominates the whole of the gallery space, allowing it to be seen would have deprived other exhibitions of the additional area afforded by the gallery’s walls, a problem solved by the fabrication of the wall and little spur gallery. As Tilted Arc might have engaged in a dialogue with subsequent plaza interventions (and still could, were it restored to the plaza), so the pre-museum-expansion Gutter Corner Splash made its statement of permanence in a conversation with the museum. And the language the sculpture and gallery spoke was no less articulate for its limited vocabulary: the binary architectural interventions of wall and not wall. Unlike the pieces from SFMOMA’s permanent collection that rotate in and out of its galleries, or OMCA’s orphaned objects, Gutter Corner Splash could never be completely forgotten. Like the pea under the mattress, the unlabeled gray space on the museum’s fourth floor plan confirmed the sculpture’s presence.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Richard Serra: Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift, 1995. This video depicts the 1995 installation of Richard Serra’s Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. See https://www.sfmoma.org/watch/richard-serra-throws-molten-lead-inside-sfmoma/. Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Did Gutter Corner Splash appear while hidden, even if only as an intuition? If so, were those moments of feeling, of recognition—the culmination of which were its reappearances as having been hidden—a species of Walter Benjamin’s “dialectical image”? Benjamin scholar Max Pensky elaborates on the concept:

Under conventional terms “past” is a narrative construction of the conditions for the possibility of a present which supersedes and therefore comprehends it; Benjamin’s sense, on the contrary, was that “past” and “present” are constantly locked in a complex interplay in which what is past and what is present are negotiated through material struggles, only subsequent to which the victorious parties consign all that supports their vision of the world to a harmonious past, and all that speaks against it to oblivion. . . . Benjamin was convinced that behind the façade of the present, these otherwise forgotten moments could be recovered from oblivion and reintroduced, shoved in the face of the present, as it were, with devastating force.24

Gutter Corner Splash, with its wall, flashed not only the vanquished Splash Piece: Casting into the consciousness of the visitor. It also shoved into our faces the fact that the museum had made, and makes, curatorial decisions to show or not show an artwork. While obvious on one level, this fact becomes invisible in the flow of an exhibition, as invisible as the warehouse in which the absent artworks reside after they are judged no longer “relevant.” Gutter Corner Splash, revealed then hidden, had been a proxy, a representative, for all warehoused works, for all works that yearn for presence, even permanence. It thrust into consciousness the subjectivity of classifying systems as well as the drumbeat of change and innovation that governs the art historical narrative. In this way, the collaboration between Gutter Corner Splash and the wall reversed the stain of “autonomy” that Kwon claimed was the effect of refabrication, and not just because the sculpture, even without the wall, reasserted the “phenomenological” power native to Kwon’s first category or because it embodied the “nomadic” soul of her third category. As dialectical image, the Gutter Corner Splash/wall collaboration also delivered the punch of Kwon’s second category, the “social/institutional,” exemplified by works that critique museums as institutions. So although it is a gift that the sculpture is now always on display, because it will cement the work’s rightful place in the current narrative, this shift also sacrifices the critique that the sculpture/wall had broadcast: the objects we discard still make a claim on us, and return; and when they return, they regain a status as new without relinquishing their status as old. The amazing thing about this state is that the museum, as well as its visitors, had become the audience for a critique, however unwitting, of its own design.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Richard Serra: Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift, 1995. This video depicts the 1995 installation of Richard Serra’s Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. See https://www.sfmoma.org/watch/richard-serra-throws-molten-lead-inside-sfmoma/. Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Over Time

Serra imagined that the Gutter Corner Splash installation crew might have initially thought, “Am I really going to have to sit here chopping lead all night?”25 Over time, however, the crew became “convinced that the efforts were worthwhile.”26 I take this musing as a parable. Its lesson is that we cannot know the full meaning of things until we have achieved an impossible state: knowing them over time, ultimately forever.

Here, then, is the solution that Jorge Luis Borges might propose in response to the problem of the history-revising museum that Benjamin raises. As a museum’s narrative changes, there would be built a new museum, leaving intact the old museum as a manifestation of the old story. The result would be a continent as encrusted with museums as this gallery’s floor is populated, one after another, with lead gutters. The continent and the gallery each form a temporal as well as spatial record of every iteration. Gutter Corner Splash whispers a more practical alternative: the tender proliferation of points of intransigence, works that cannot be disconnected from their places or their moments, whose stories cannot be reconceived, revised, or dismantled, and who recount them again and again.

I imagine myself floating above the earth, looking down on other intransigent structures—Stonehenge, Easter Island—whose site-specific meanings are now only conjecture. Zooming from the heavens into the SFMOMA no-longer-a-spur gallery, I know that, once, hidden behind a wall was a work whose story could be untold only by the destruction of its site. Indeed, at times it had seemed as if an earthquake could flatten San Francisco, and yet this thing would remain in place, unshaken, hanging in air, the single reference point around which the city would be restored. For Gutter Corner Splash, the compromise with the museum—the barter of presence for absence—was no compromise at all, but was an exchange for the privilege of delivering, in collaboration with the wall, an insight that would otherwise have been—and now is—lost.

Miwon Kwon describes “the history of avant-garde . . . art practices . . . as the persistence of a desire to situate art in ‘improper’ or ‘wrong’ places.”27 She suggests that this desire might be wrongheaded, that in fact there is no right place. Gutter Corner Splash, in its fraught, pre-museum-expansion condition, embraced place just as quantum physics would propose it: as multiple simultaneous states. In such a place, art was ongoing if unseen, burdening and blessing the museum with its immovability, freeing and flustering the institution with its impermanence, being right and being wrong. Neither artwork nor institution could ultimately assert the greater control.

Ironically, by apparently ceding authority to the permanently exposed sculpture, SFMOMA has seized authority back, forcing Gutter Corner Splash into a new compromise. For most, the sculpture’s new accessibility is a gift and a testament to the success of the new museum and the creativity of its curators. But the time-shifting—the scarification ritual that reveals history as process rather than product—will heal over and leave nary a blemish, except perhaps for an ache among those of us who knew the sculpture when its invisibility was as prominent as its display.

Rob Marks writes about art and aesthetic philosophy. He has published regularly on the museum experience for Art Practical and Daily Serving, and has written extensively on the work of Richard Serra. His chapter “In the Body’s Space, the Body’s Time: Feeling Your Way Through Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time,” is forthcoming in Sarah Lippert’s Space and Time in Artistic Practice and Aesthetics (I.B. Tauris). He has a MA in Visual and Critical Studies from the California College of Arts and a Master of Journalism from the University of California, Berkeley.