The stereotype is only a remnant—as a result of having been multiplied—of an original emotion. Its accentuation ends up evoking a lack in the contemplative viewer: the nostalgic intuition of what the original object of that voluptuous emotion might have been, or simply the emotion itself, or the obsessional fantasy. …The interpretative function of the stereotype is to conceal, but if it is accentuated in excessive proportion, it becomes a critique of its own concealment.

–Pierre Klossowski in conversation with Ann-Marie Lugan Dardigna,

Klossowski: L’Homme aux simulacres

(Paris: Navarin, 1986), 29.

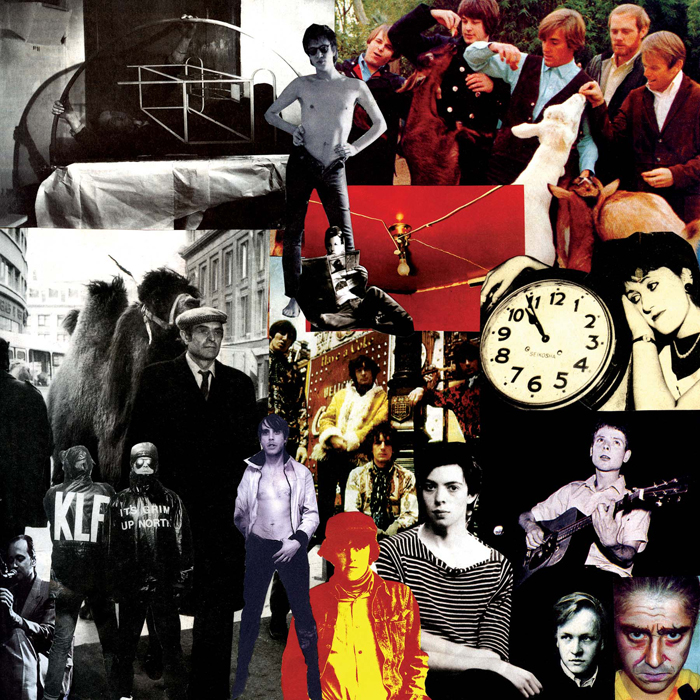

Screwball Asses, inspired equally by writer Pierre Klossowski and queer theorist Guy Hocquenghem, examines a range of gay stereotypes that inform gay male identity. Most of the imagery in this group show at The Company is appropriated and seems to pick up where Andy Warhol’s film projects and drawings ended. Screwball Asses simultaneously titillates and repulses, exposing gay sensibilities that run from the flaming to the hyper-virile. Much of the work focuses on the history of gay male subversion from the heyday of the late sixties to the glam of the seventies and eighties. Curators Hedi El Kholti and David Jones posit stereotypes not as marks of shame but as lenses that elucidate the experience of life and captivate the imagination.

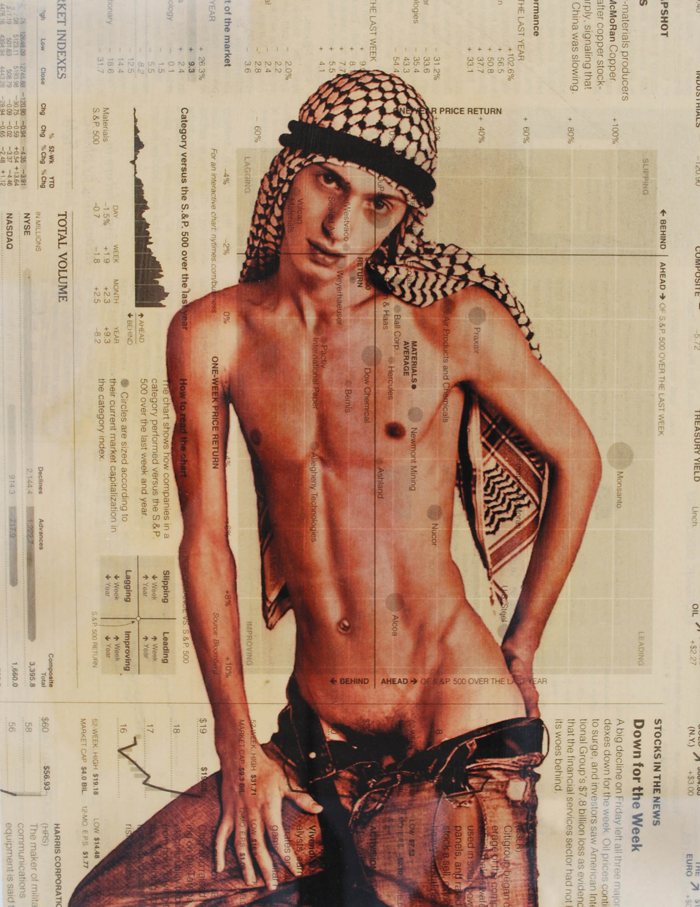

Representative of the curators’ fascinations, Slava Mogutin’s Stock Boys Series of archival, inkjet prints on canvas board are simultaneously sincere and sarcastic. In Stock Boys Series #1 (2008), a young boy in an Arab headdress leans voluptuously. His hand grabs his thigh and his elbow is posed contrapposto, revealing pubic hair that peeks from the top of flesh tone pants. The image, taken from an erotic magazine, is printed on top of the Wall Street Journal stock reports on the value of oil. Making literal a relational intercourse between the viewer and the boy, the stereotype here is both hideous and totally revealing as wider cultural criticism of our own role as exploiters of the Middle East and her bounty here portrayed. In Mogutin’s hands, the image of a young Arab supplicant, like that of T.E. Lawrence’s companion Selim Ahmed, also known as “Dahoum” (or “little dark one”), is both shocking and poignant as it reveals a historic stereotype that functions exactly as Klossowski imagined. To an Anglo, the eroticism of image of a Middle Eastern lover is perhaps sevidence of the Anglo’s sense of anxiety in regards to the imbalance of power between self and other in the relationship. Anxiety is relieved in the body in different ways, chiefly through laughter and orgasm. Viewed with this understanding, the ethnic stereotype reveals a masturbatory power game that privately alleviates tensions in the viewer, here envisioned as a reader of the financial section.

Slava Mogutin’s other images of ethnic fetishism and rock-hard skinheads highlight the charge and self-critique of erotic stereotype. The viewer becomes aware of how repressed the stereotype is in our cultural awareness and how shamefully exciting it remains to reveal a latent image. Excitement results from the transgressive act of pushing the intimacy of private experience into a closet and then ripping it back out again in the form of radical exhibitionism. The term “queer” and its history have long been emptied of accusation and shame within gay culture. Much like other ethnic and cultural epithets, “queer” is not offensive if used by the object-as-subject. The curators seem to play with notions of sadistic power as a type of sexual transgression that both oppresses and liberates.

The transgression, however, is ultimately pretty narrow, since the “queer” proposed by the curators is predominantly male. Ironically, Guy De Hocquenghem was the first male member of the Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire (FHAR), a group founded by militant lesbians whose purpose was to fight the stereotypes of bourgeois homosexuality. Sadly, Screwball Asses’ exclusion of lesbian imagery disenfranchises half of queer culture. One could imagine a whole range of lesbian imagery that would fit within the prescribed scope of the show. After all, the terms queer, homosexual, gay, and lesbian represent very different understandings of the gay experience as well as differences in power relations based on identification. The stereotypes associated with eroticism in lesbian culture are often based on machismo and the games associated with male power, an example being the “wife beater” t-shirt, a dyke fashion statement that creatively appropriates a repressive male stereotype.

The juxtaposition of Gary Lee Boas’s photographic portraits of small town performers in the 1980s with Sheyla Baykal’s portraits from the 1970s of friends from New York’s Lower East Side exposes another gay male stereotype elaborated on in Screwball Asses, that of drag queen or lady boy. Baykal left the Ford Modeling Agency to collaborate with Peter Hujar in documenting seventies drag queens and burlesque stars of New York. Boas shows a parallel subculture, the drag show pageant scene of South Central Pennsylvania. Compare the grit and honesty of Boas’s striking portrait Eddie, Lancaster, PA (1985) with that of Sheyla Baykal’s portrait, Peter Hujar as Candy Darling (1973). In each form of portraiture the models exhibit an awareness of being looked at and pose for the camera. Boas’s staging is crude while Baykal’s is slick and stage-lit, like one of George Hurrell’s movie star portrait from the forties. Boas’s character, Eddie, has an underground quality that stands in contrast to that of “Warhol Superstar” Candy Darling from Baykal’s portrait. Boas’s Eddie is literally torn in half by his gender identity—half of his body, hair, and makeup are that of a female and the other half, including facial hair, is distinctively male. As played by Hujar, Baykal’s Candy Darling is in contrast fully female with certainty, pretense, and pleasure.

Since these photographs were made, our culture has become more accustomed to transgender images. By their inclusion in the exhibition, Boas and Baykal’s portraits recall a time when the risk of dressing in drag was greater because it was less socially recognized. The drag queen character’s burlesque or circus-side-show status is emphasized and then stripped away by Boas in images like Miss Gay Marilyn 1993, Lancaster, PA (1993). Here, Marilyn appears bald under a wig stocking. As she applies lipstick in a backstage area, or perhaps a cheap apartment, her pristine and corpse-like reflected image is rendered real by the frailty of her baldness. In Baykal’s portrait Jackie Curtis (circa late ‘70s) the drag queen is staged as a career woman in office attire. Behind her a framed movie star portrait hangs on the wall. Baykal’s subject stares in a seductive manner from atop an office desk, ready for action. His Jackie is as liberated as the Mary Tyler Moore-type career girl she seems to be playing. Whether covered up by Baykal or exposed by Boas, the queen as stereotype is revealed. It is worth noting that all of the Baykal photographs in the show were made available thanks to performance artist and playwright Penny Arcade (born Susana Carmen Ventura). Arcade’s thirty-year career as a performer focused on sex and censorship. One of the characters she famously assumed is based upon “Margo Howard-Howard,” a fifty-year-old drag queen. Arcade’s first significant performance was as an actress in the Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey film Women In Revolt (1971). An autobiographical trilogy of her plays, Bad Reputation, will be released by Semiotexte in October 2009.

The use of appropriated imagery is at its most inventive in the work of co-curator David Jones. His stop motion animation The Secret Love of Jesse James (2009) is based on the theme of satyriasis, a condition of excessive and often uncontrollable sexual desire in men. Jones uses still photography to create crude, collaged animation of two “Marlborough Men” out in the desert. With jointed appendages that move in mechanical motion, we see the cowboys meet, ride Brahma bulls, flirt, kiss, and consummate. The music and text interspersed throughout lends romance and drama to an otherwise rather awkward look at romance and violence out in the Wild West of hookups. There is something touching and silly about Jones’s desire to create a handmade Brokeback Mountain, this time with cuter guys who go all the way on camera. The dualistic sentimentality and eroticism in Jones’s video is amplified through hand-chalked text, expressing such statements as, “this thing that won’t stop or go away,” and “I never felt it stop until my heart went dead.” For the closing sequence of the video, Jones lights fire to some of the collage itself, adding an apocalyptic “The End” for the audience and his young lovers.

The most thoughtful deliberations in the show are evidenced in the writings of co-curator Hedi El Kholti. Clearly El Kholti has a gift for language and intellectual syncretism. His fanzine When You Read This I’ll Be Gone contains myriad references to art and literature, as well as a fascination with Guy Hocquenghem. Both a journal of the show and a glimpse of El Kholti’s far-reaching mind’s eye, this tiny, unassuming, silver book contains the heart and asshole of Screwball Asses. El Kholti draws from emblematic cultural icons and friends that guide his practice and experience in order to create his work. A confluence of events, scenes, images, personal dilemmas, and memories of sexual awakening, the book’s specter is the exhibition itself. El Kholti’s memories resonate throughout the exhibition in the imagery of other artists. Works like Paul Gellman’s Kimono (2009) and Les Amours de Jupiter (2009) by Donnie & Travis illustrate small details of El Kholti’s book, such as a memory of his mother, a model on a photo shoot in the desert, and the brevity of summer love in Morocco. In the end, El Kholti’s personal narrative rather than any overt stance on the recontextualization of the term “queer” drives the exhibition.

Screwball Asses seems comfortable with its own pandering of gay stereotypes. It’s as though the struggle for gay liberation is completely over and we are living in a time of total equality and celebration. Unfortunately, for many Americans the question remains whether gay rights are indeed civil rights. Interestingly enough, during the run of the show in Los Angeles, the California Supreme Court upheld Proposition 8, known as “The California Marriage Protection Act,” effectively eliminating gay marriage rights in the state. Perhaps the next show that Jones and El Kholti curate should focus on the relationship of the gay rights movement to the civil rights movement. Such a show would be an interesting foil to Screwball Asses and function to uphold the diverse notions of Guy Hocquenghem and FHAR.

Mary Anna Pomonis is an artist and a writer living in Los Angeles. Her artwork and life focus on the mimetic practices of writing and drawing.