In the essay “Turning,” published by e-flux in 2008, theorist, curator, and organizer Irit Rogoff responded to the proliferation of art making that engages themes of pedagogy or education—what had recently been termed the “educational turn” in contemporary art.1 Rogoff’s writing was not wholly celebratory, though she clearly affirmed the potential of this expanded production. One of the criticisms Rogoff launched was aimed at the development of an aesthetics that she argued had become a kind of visual shorthand for pedagogy. “[A] table in the middle of the room, a set of empty bookshelves, a growing archive of assembled bits and pieces, a classroom or a lecture scenario, or the promise of a conversation have taken away the burden to rethink and dislodge daily those dominant burdens ourselves,” she wrote.2

Returning in the present moment to Rogoff’s concerns with what she termed “pedagogical aesthetics” allows us to chart the history and better contextualize the current stakes of the continued proliferation of this form of production. These works also provide a counterpoint for considering artistic practices that engage pedagogy or education from an active and explicitly political standpoint, such as many of those discussed in a recent book edited by Tim Ivison and Tom Vandeputte, Contestations: Learning from Critical Experiments in Education.

Since Rogoff’s text was first published half a decade ago, the turn it discusses has gained momentum. Take, for example, independent artist-run schools, one of the many phenomena associated with the educational turn in art. As evidenced by the 2012 Frieze article “New Schools,” just mapping these projects is now a formidable task, to say nothing of the symposia, conferences, and exhibitions that have proliferated alongside them. Though clearly the forms associated with this turn do not all bear the markings of pedagogical aesthetics, the use of the formats Rogoff highlights in “Turning” have certainly multiplied. For these reasons, Rogoff’s weariness with the phenomenon of pedagogical aesthetics is a sentiment that is now more widely shared. And so, in a moment when weariness risks becoming exhaustion, it has become increasingly important to parse the differences between works recycling a hardened pedagogical aesthetics, primarily functioning to represent an absent process, and those that are finding ways to activate the political potential of a truly process-based pedagogy. Mapping these actively political strategies in the contemporary arts is one the chief contributions of Contestations.

The book is small enough to fit in a back pocket, and there is an almost playful stealthiness to its design. Like construction paper jackets over illicit magazines, the simple cover gives little indication of its contents. The book jacket displays a colorful photo of overturned books, seemingly littered across a plaza, and one word—Contestations—is printed on the spine. The cover image documents a protest that took place on the campus of the University of California Berkeley in 2011, when student Occupy protesters responded to the forced dismantling of their encampment by leaving overturned books on the quad where the camp had been. In the photo, the books are splayed open on the pavement, mimicking the shape of the tents that had previously occupied the space.3 To those who recognize it, the image on the cover might signal the book’s political orientation; one markedly different from the practices Rogoff questioned and that have become increasingly prevalent since “Turning” was published.

Contestations’ compelling analysis of the current conditions shaping higher education may be taken to indicate that there is a strong political imperative for artists and culture workers to accept what Rogoff calls “the burden to rethink and dislodge daily.”4 Edited by London-based artist and writer Tim Ivison and writer and editor Tom Vandeputte, Contestations features essays from a host of contributors from the United States and Europe, including Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Sean Dockray, Jakob Jakobsen, Nils Norman, Gregory Sholette, and the collective Ultra-red. In their introductory essay, the editors frame the contributions as “critical reflections on education as a form of political engagement.”5 The aims of this political engagement are also offered, albeit in broad terms: “[W]e seek to underline a common project that all of these practices, to a greater or lesser extent, seem to share: the contestation of the current direction of academic institutions, and the attempt to rethink the structures and spaces of learning on a fundamental level.”6

Of course, this drive to interrogate the state of postsecondary education is not unique to Contestations. In the late 2000s, when this “educational turn” was newly declared, the effects of the Bologna Declaration reverberated through the fields of higher education in Europe. Describing the effects of the policy, the editors of Curating and the Educational Turn wrote that the Bologna Declaration marked a political reorientation of academic education in Europe, newly configuring the system around the values of “inter-operability of service provision and a system of exchange equivalence for ‘outcomes’—a common market.”7 In other words, the declaration reframed higher education away from pure scholarship toward a more pragmatic education in support of globally expanding markets. The desire to critique what Contestations’ editors frame as the “current direction of academic institutions” has not weakened over time.8 Present in many of the essays in the book, the issue is summed up by Italian writer, media theorist, and activist Berardi. In an interview with the editors, he argues that post-secondary educational institutions’ subjection to these “neo-liberal” policies has effectively ended their epistemological independence, reducing “research and discovery…to instruments for economic competition.”9

In the introduction to A Brief History of Neoliberalism, David Harvey defines neoliberalism as “a theory of political practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade.”10 Since the 1970s and 1980s, governments the world over have deregulated a host of markets and privatized industries, many of which were providing public or social goods that were previously considered to be best provided through the state. This shift has had significant effects on the field of higher education in both Europe and the United States, as neoliberal policies in education effectively force universities to operate according to market logic. This assault has intensified since the global financial crises; as Ivison and Vandeputte write in their introduction, “[A]usterity policies in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis has [sic] resulted in a sustained attack on education…. The purpose of the university is increasingly understood in terms of attendance numbers, evaluation procedures and efficiency regulation; institutions are forced to restructure, commodify, privatise and close down departments that do not conform or compete.”11

A version of this broad-based critique is often present in the literature associated with the educational turn in art, but an analysis of cultural production in relation to specific policies and events can generate a more nuanced understanding of the political stakes of this work. This is one of the chief contributions of Dockray’s essay for Contestations. In “Openings and Closings,” the Los Angeles-based artist examines current policies and conditions affecting post-secondary education—an analysis that also crucially frames a field of possible action. Dockray is the founding director of Telic Art Exchange, the non-profit arts organization in Los Angeles that initiated The Public School, an educational platform, and AAAAARG.ORG, a website for sharing and accessing academic texts free of charge. Many of these types of texts are made available to students and faculty at degree-granting institutions through subscription-based services like JSTOR. But for those unaffiliated with such institutions, access would require costly journal subscriptions.

In “Openings and Closings,” Dockray analyzes seemingly disparate conditions on post-secondary campuses and in higher education, beginning by recounting a number of events occurring in recent years that demonstrate the militarization of college campuses. The examples are global in scope. In 2011, Sao Paulo’s military police arrested seventy-two protestors responding to the lifting of a decades-old ban on police presence on campus.12 The same year, a thirty-five year ban on police access to university campuses in Greece was abolished; the change was motivated, Dockray writes, by politicians’ desire to “effectively implement austerity measures imposed by European financial interests.”13 This event occurred just ten days before the now infamous “pepper spray incident,” when the University of California Davis responded to a peaceful protest on their quad by pepper-spraying students at close range.14

Berkeley Book Tents, 2011. After being evicted from the UC Berkeley campus in the autumn of 2011, student Occupy protestors left books where their tents once stood. In 2009, students across the University of California system protested against an unprecedented 32 percent rise in tuition fees. Photo: Arturo Snuze.

In Campus Security, published by Semiotext(e) for the 2014 Whitney Biennial, UC Riverside professor Jennifer Doyle relates the decisions of the UC Davis administration and the campus police department that lead to the confrontation and the violence of the encounter between students and the police. Doyle’s and Dockray’s discussions of this incident share more than subject matter. Both offer a careful recounting of the event, though Doyle’s essay renders the story in greater detail. She conveys the bizarrely conciliatory dialogue between the police and students in the moments before the students were pepper-sprayed; scrutinizes the official and unofficial language of the administrators, both prior to and after the event; and returns again and again to the images of the violence. Her often deadpan reconstruction slows things down, in a rhetorical move that forces reflection deeper than is typically garnered by a flashing video on a laptop screen—the way so many have experienced this event.

In “Openings and Closings,” Dockray argues that the (re)militarization of post-secondary campuses often takes less obvious forms. His examples range from police enforcement of copyright law in Brazil to the banalities of the password firewalls that are routinely required for academic participation. Dockray describes the similarities between these disparate realities of campus life: “In the inconveniences of proximity cards, accounts and login screens we discover the quotidian dimension to the militarization of the university,” each of which is a part of larger systems that are designed for “policing access.”15

The routineness of firewalls and ID card checks obscures the latent violence that can erupt in the enforcement of these “inconveniences.”16 Doyle describes a situation that began when student Mostafa Tabatabainejad was singled out for an ID check in a UCLA library in 2006.17 As Doyle writes, “ID checks are controversial on every campus as men of color are selected for the college edition of ‘stop and frisk.’”18 When Tabatabainejad refuses to show his ID card, this encounter with campus security soon became one with the police.19 The confrontation escalated when Tabatabainejad, who had begun to leave the library when the police arrived, went limp in their arms. The police responded to this form of passive resistance by using a Taser on him multiple times.20

For many students attending both public and private universities in the United States, the terms of access are clear. They can expect to be saddled with un-repayable student debt and to participate in a learning environment that is tightly controlled. But this has not always been the case. Instead, it is a product of the current neoliberal political climate, in which “the state is acting to produce and defend a structure that generates wealth from the process of education.”21 Dockray argues that this wealth is protected and accumulated through regulating the various forms of access required for participation in academic learning environments, including the ID card checks, passwords, and other “quotidian dimension[s] to the militarization of the university” described previously, as well as the more blatant examples of this militarization in recent years.

In closing, Dockray notes a historical shift in the forms of access policed by academic institutions. “If access has moved from a question of rights (who has access?) to a matter of legality and economics (what are the terms and price for access, for a particular person?), then over the past few decades we have witnessed access being turned inside-out…. [W]e have access to academic resources but are unable to access each other.”22 One method to gauge the extent to which this access to each other is indeed under threat is to return to Dockray’s early discussion of police presence on Greek campuses. Here, the artist notes that UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi (also a key figure in the pepper spray incident described above) was involved in a report recommending the Greek government lift the decades-long ban against police on Greek campuses. The report made note that “the politicisation of students…represents a beyond-reasonable involvement in the political process,”23 an admission from the administration of the risk they perceived.

The point of my sustained focus on a singular essay from Contestations is twofold. The first intention is to highlight the urgency of the discussion in Dockray’s article and the mirroring of concerns raised recently by Jennifer Doyle. It is also to underscore these texts, and the conditions they outline, as critical points of departure for artists and cultural producers working now. Dockray offers his own ideas for moving forward, and ends the essay by arguing for the development of a pedagogy that intentionally breaches these points of access. I hope this call will resonate with culture workers struggling with how to engage this set of conditions.

The proposed course of action suggested by Dockray might be understood in relation to Rogoff’s notion of emergency versus urgency. In “Turning,” she writes,

I would suggest education to be the site of a shift away from a culture of emergency to one of urgency. Emergency is always reactive to a set of state imperatives that produce an endless chain of crises, mostly of our own making. So many of us have taken part in miserable panels about “the crisis in education.” A notion of urgency presents the possibility of producing an understanding of what the crucial issues are, so that they may become driving forces.24

In sketching the contours of a crisis, Dockray highlights the urgency that may motivate further enquiry. But what is crucial in refuting an emergency mentality that could equally take hold is his provision of possible points of departure, the forms of which are not dictated by the crisis itself, unlike a more reactive type of engagement.

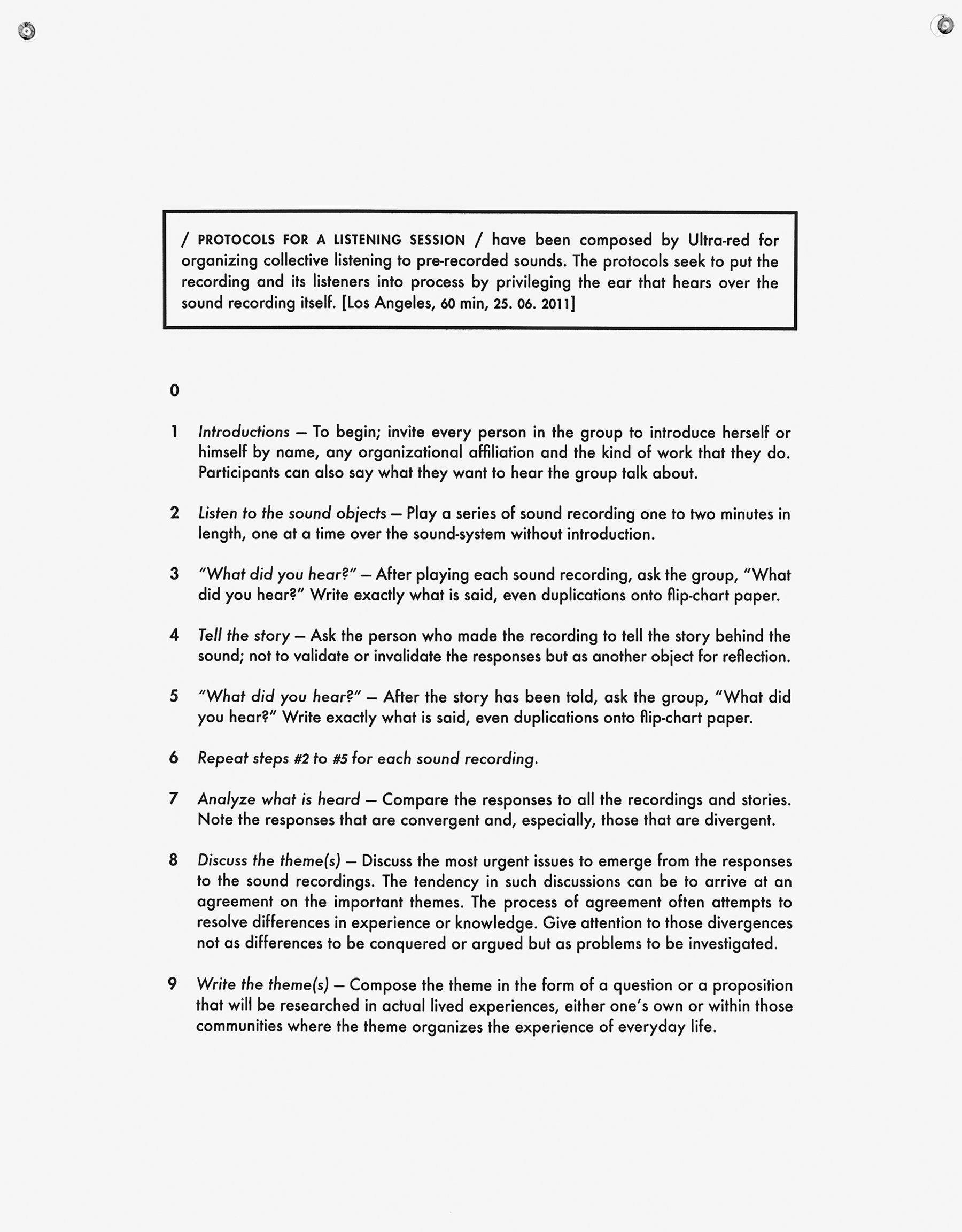

Ultra-red, The Protocols for a Listening Session, 2011. The Protocols for a Listening Session describe Ultra-red’s use of group discussion, recorded sound, and writing as techniques for the collective investigation of political issues. These protocols were used internally by Ultra-red in Los Angeles only in the planning stages for School of Echoes. Courtesy Ultra-red, 2011.

“Openings and Closings” is not the only essay in Contestations that might be understood to reflect Rogoff’s distinction between emergency and urgency. In the interview, “What is the sound of radical education?” members of the international sound collective Ultra-red demonstrate how the group puts the pedagogical in service of the needs and desires of diverse communities, citing examples of how they have employed the collectives’ listening-centered approach to popular education within community organizing spaces. While “What is the sound of radical education?” provides context around the individual political organizing work of its members, in their 2011 text, “Andante Politics: Popular Education in the Organizing of Unión de Vecinos,” the collective explicitly outlines its methodology.25

In “Andante Politics,” Ultra-red member Dont Rhine parses the differences between political activism and organizing, differences that bear similarities to those articulated by Rogoff between emergency and urgency.

The crises in capitalism lead resistance from one skirmish to the next. Wearingly, activism synchronizes itself to capital’s tempo. On the other hand, political organizing, whose pace distinguishes it from activism, has the potential to organize time differently. The disorganization of the temporality of the crises in capitalism is one device in the conjecture between political organizing and the cultural actions of popular education. Were it scored for musical performance, popular education would be denoted andante; a walking pace sustainable over the long period.26

Ultra-red’s use of the musical term andante highlights the political considerations inherent in the speed at which their work is undertaken, reflecting the collective’s sustained (and as Rhine states, sustainable) commitment to community organizing. This is clear in their contribution to Contestations, where member Leonardo Vilchis discusses his work with residents of Maywood, California. For ten years, Maywood residents have been working to learn how to take over management of the water supply in their city. The process demonstrates the depth of commitment required by this andante approach to organizing through popular education, as well as the political possibilities of this work.27

Contestations highlights a set of approaches that come directly from artists’ practices that both map and respond to current conditions within post-secondary education and beyond. These practices, such as that of Ultra-red, demonstrate the potential of truly process-oriented forms of pedagogy and deal a serious blow to the perceived political relevancy of practices associated with what Rogoff termed pedagogical aesthetics. If emergency culture is not going anywhere, and the crisis in education continues to take on new permutations, it is imperative to consider what can be accomplished at a sustained, steady pace, rather than in the short sprints of emergency-driven forms of political engagement.

Jacqueline Bell is an independent writer and curator, and is currently completing the Walter Phillips Gallery Curatorial Research Work Study at the Banff Centre. She is a member of the team producing Social Practices Art Network, a media platform for a variety of socially engaged art and design practices, and is a graduate of the M.A. Art and Curatorial Practices in the Public Sphere program at the University of Southern California.