It’s very fancy

on old Delancey

Street, you know.

The subway charms us so

when balmy breezes blow

to and fro.

–Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, “Manhattan”

Delancey Street spans the eastern half of lower Manhattan for one mile between Bowery and the Williamsburg Bridge. The street is an historic thoroughfare for New York’s Lower East Side—once a traditional Jewish neighborhood, characterized by pushcarts, synagogues, and tenements; now punctuated by nightclubs, eateries, and art galleries. From the glamorous heights of the 1920s, the area slid into the neglect that famously incubated the New Bohemia of the 1960s. On 2nd Street, on the Lower East Side, Claes Oldenburg staged his Store (1961), filled with enameled plaster sculptures of consumer goods, on a block that “might have needed an actual supermarket rather than a dubious bodega.”1 The work confounded neighbors and critics alike. Months later, these sculptures appeared in his uptown gallery and “voilà!” They made sense, the critics got it, and the work resolved into the matrix of art history, flanked by precedents and contemporaries from Duchamp to Jasper Johns.2 Two decades later, Madonna would meet Basquiat at a Lower East Side night club. Today art on the Lower East Side no longer impinges on the working class grind, but instead reflects a history of transposition: downtown to up, lowbrow to high—and now, so it seems, vice-versa.

Urs Fischer, big foot. 2014. Installation view, Gagosian Gallery at 104 Delancey Street, New York, 2014. Cast bronze; three parts: foot: 61 × 62 × 94 inches; large rock: 26 × 39 × 37 inches; small rock: 7 × 20 × 9 ½ inches. © Urs Fischer. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.

In the spring of 2014, one could witness several weird permutations of this process within a few Delancey blocks. At 55-D, James Fuentes Gallery staged The Real Estate Show Was Then: 1980 (April 4–27), an exhibition of works from the eponymous “extra-legal” art show that took place five blocks east at 125 Delancey.3 That building, demolished in the early 2000s, is now a parking lot awaiting development as part of the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area, or SPURA—a notoriously cumbersome city project first proposed in the 1970s but only fully planned in 2013.4 Across the split lanes and median, at 104 Delancey Street, dealer Larry Gagosian had temporarily set up shop in a former Chase Bank branch. There, for mermaid / pig / bro w/ hat (April 3–May 28), laissez-faire “neo-dada” sculptures by Urs Fischer splatted against what the artist has called “cat-food colored Modernism.”5 Instead of a teller, a hand-gouged bust of Napoleon sat on the counter; behind it, under a dimming Chase logo, the backlit wall display had been ripped down; a bluish rectangle lined with LEDs remained. In a back room, a big severed foot engaged in formal play with a rectangle of unpainted drywall. A boy sodomized a pig in the kitchenette. Fischer’s punny work, usually burdened by art history, seemed somehow freed by the building’s atmosphere of abandonment and apocalypse. Uptown, though, at Fischer’s concurrent last supper at Gagosian proper (April 3–May 8), the white walls stultified. A single sculpture, his hand-raked riff on said tableau, looked stupid. “Divorced from its downtown context,” wrote Corrine Fitzpatrick for Artforum.com, “the work itself does not seem worth the follow-up trip.”6 Brienne Walsh, covering both Fischer shows for Art Review, conceded, “Perhaps the context was at fault, not the work. My neural pathways may be wired in such a way these days that all I can feel in a white cube space is apathetic disgust.” While back on the Lower East Side, Walsh wrote, “Is it horrible to say that I loved it?”7

Urs Fischer, mermaid / pig / bro w/ hat, exterior view, Gagosian Gallery at 104 Delancey Street, New York, 2014. © Urs Fischer. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.

Behind the ex-bank’s graffitied facade (and nearly every reviewer takes care to say it’s got graffiti on it8), Fischer’s bronzes dithered between being blue chip art and piles of lowbrow slag. Gagosian staff added to the postmodern boutique atmosphere. Two gallery assistants sat at a desk in a glass walled office, like bankers. Half a dozen guards in black suits milled around—gallery security acting like bank security. Fischer’s scatological little sculptures, which were largely shaped from mounds of raw clay by volunteers during his 2013 show YES at the Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles, have been cast in bronze. Some are silver- or gold-plated—transubstantiated, gentrified.

The Chase branch in question, once a Washington Mutual, had been vacant for two years; across the closest intersection, at the southwest corner of Essex and Delancey at 109, is an active Chase. Indeed, gentrification was the joke behind the Gagosian pop-up. The gallery was slumming it. Fischer’s sculptures, usually playing bad boy to the institution, here seemed almost transgressive—truly not belonging. There was something thrilling for the viewer, too. Like Gagosian, one could play pioneer—given the opportunity not only to witness contemporary art, but to explore a contemporary ruin. Gagosian staged a gentrification drama—a Lower East Side story—occupying a symbolic vacancy left by an all too actual recession. As much as Fischer’s crowd-sourced sculptures are parodies of spontaneous collective effort, this “occupation” is the cynical inverse of the extra-legal “pop-up” at 125, thirty-four years and a four-lane road away.

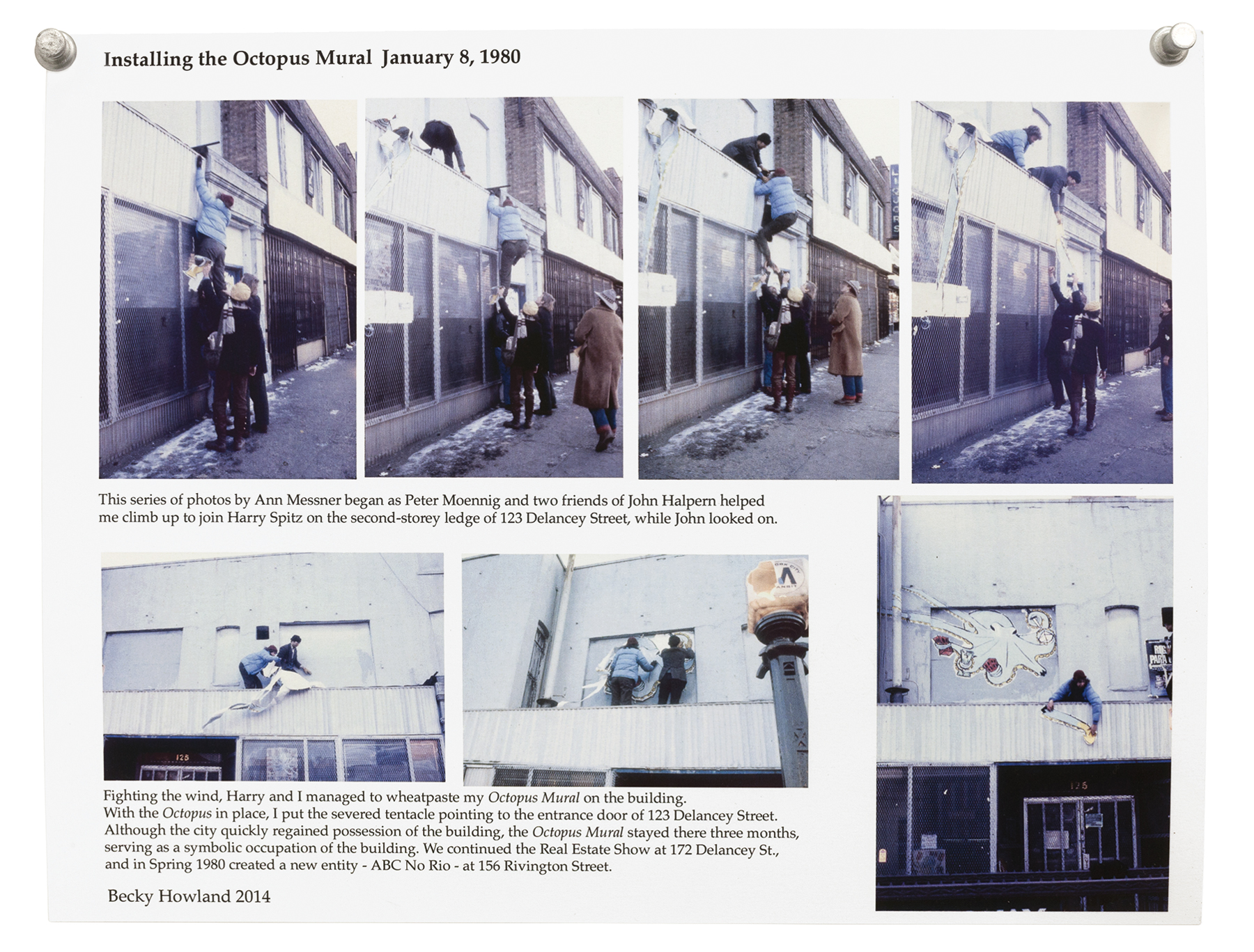

Becky Howland, Installing the Octopus Mural, January 8, 1980, 2014. Installation view, The Real Estate Show Was Then: 1980, James Fuentes LLC, New York, April 4–27, 2014. Photo: Jason Mandella.

Meanwhile, James Fuentes hosted a more explicit, perhaps more faithful, transposition. The Real Estate Show Was Then: 1980 included reproductions, reinstallations, and new versions of work made for the 1979–80 Real Estate Show, the open call exhibit organized by members of Colab (Collaborative Projects) in a Delancey Street squat. The show opened News Year’s Eve; by January 2nd, the police had changed the locks. Yet, almost by accident, this artists’ resistance would pay off. The Real Estate Show artists had provoked a city weary of controversy surrounding the long-delayed SPURA, which had already displaced thousands of Lower East Side residents but, as of this writing, has yet to break ground. New York City, rather than endure still more bad PR, offered Colab their choice of other abandoned properties in the area; they eventually settled on 156 Rivington, one block north of Delancey, and founded the art and performance venue ABC No Rio.9

This kind of civic generosity would be incredible today; imagine, for example, Mayor Bloomberg and the NYPD providing Occupy Wall St. with a list of other parks in which they might squat, indefinitely. The RES remains a high water mark in the history of artist activism. After decrying the real estate manipulations then facing New York’s poor, Colab’s original Real Estate Show manifesto ends with the line: “It is important to learn.” Yet as police, landlords, and politicians, as well as artists, remember the battles for SoHo and the Lower East Side, today the lessons drawn from the RES might be more abstract than actionable.

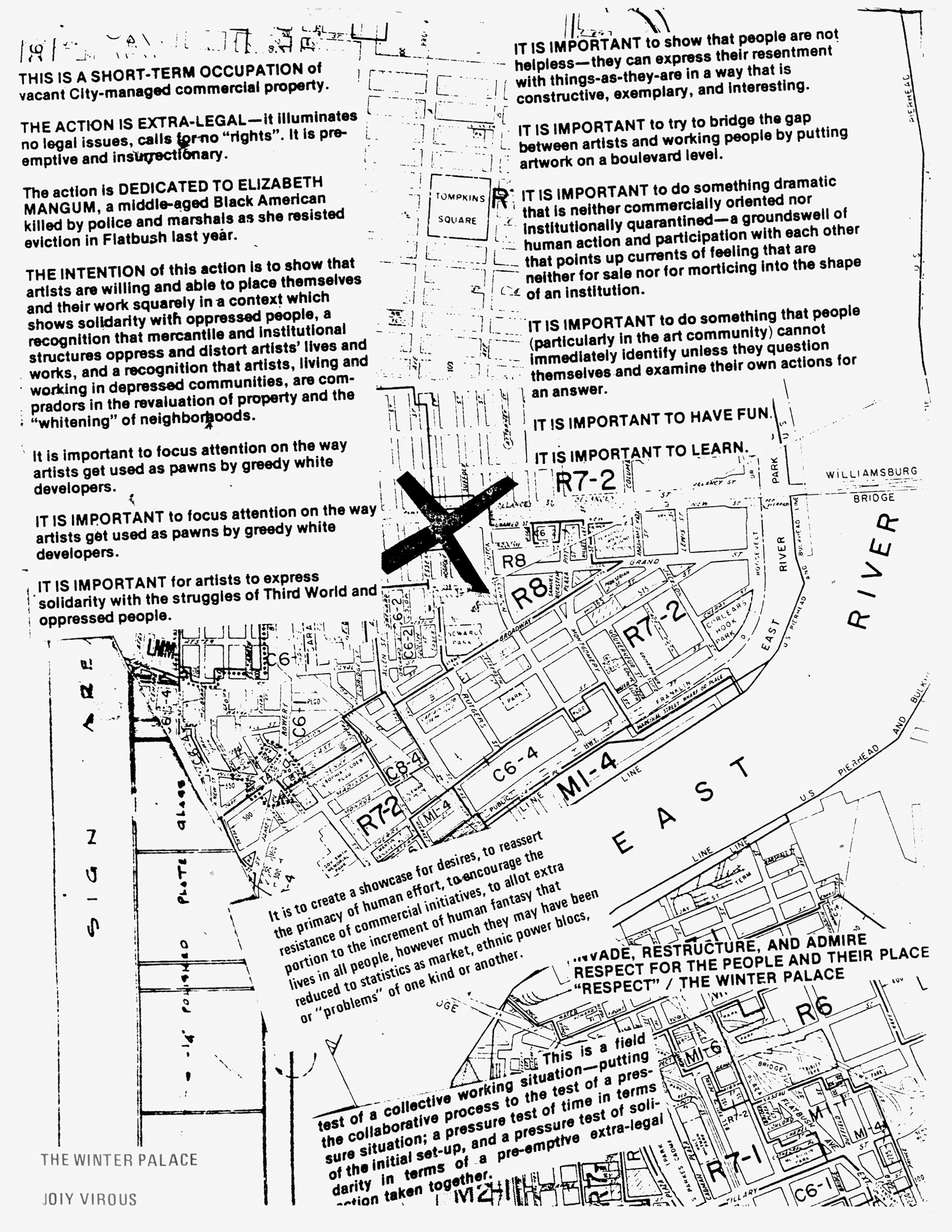

Flyer from the original Real Estate Show, 123 Delancey Street, New York, December 31, 1979–January 1, 1980. Flyer by Howland and Moore, 1979. Text by Committee for the Real Estate Show (Becky Howland, Ann Messner, Peter Moennig, Alan Moore, and others).

The Fuentes show operates less as a vital exhibition, more as a history lesson—while perhaps also angling our attention toward the current, same-but-different trends of the Lower East Side.10 James Fuentes grew up in the area, and was three years old when Alan Moore and a small crew from Colab snipped the lock on 125 Delancey Street.11 In September of 2010, he moved his gallery from Chinatown to a larger space, becoming the “only gallery on Delancey.”12 Citing the imminent first phase of SPURA, Fuentes says the Real Estate Show is “a particularly relevant history given the impending Essex Crossing project.”13 Vintage artworks, posters, and publications from the historic show were joined by documentation of the 1979 opening and subsequent press conference, as well as updated artworks. A pile of cigarette packs gathered by Robert Goldman from the surrounding streets, reprised at Fuentes, provides an odd demographic study; the present version is mostly Newports, with a sprinkling of Marlboros, Camels, and American Spirits. Other works range from quaint agitprop (a bright stencil of a worker by Walter Robinson) to militant jabs (anti-landlord sloganeering by Coleen Fitzgibbon and Robert Cuni—including a painting of a machete above the words FOR / CLOSE). A petition that circulated at the Colab-organized Real Estate Show press conference, sporting Joseph Beuys’s signature under a doodle of a hat, dangled from the wall on a clipboard. The Real Estate Show manifesto, once a Xeroxed cutup, had been properly typeset as a takeaway poster.

Robert Goldman (Bobby G.), Dead Packs, 1979. Mural by Mike Glier. Installation view, Real Estate Show, 123 Delancey Street, New York, December 31, 1979–January 1, 1980. Photo: Christof Kohlhofer. Courtesy of Becky Howland.

Robert Goldman (Bobby G.), Dead Packs Worldwide, 1979–2014. Installation view, The Real Estate Show Was Then: 1980, James Fuentes LLC, New York, April 4–27, 2014. Photo: Jason Mandella.

As with the Real Estate Show itself, however, art sometimes plays a supporting role to the action. Reporting on the Fuentes redux, writer Natasha Kurchanova put it diplomatically: “Taken separately, the aesthetic merit of these works can be discussed and disputed.”14 Critic Ken Johnson didn’t mince words: “Hardly any of it is visually compelling,” he wrote, reviewing the show for The New York Times, “but the back story is interesting.”15 Indeed, Johnson perhaps unwittingly restates the perspective offered by Alan Moore in his piece for a special “Real Estate Show Revisited” issue of House Magic: “We have known for a long while that what makes this show significant was not its content, but its circumstances and its outcome.”16 More significant than the messages of paintings and posters is the idea of artists as a (romantic, speculative) market force. The litany of artists living, working, and moving together through tumultuous New York years, often detached from qualitative judgment, exerts an almost elemental effect on the city’s neighborhoods—a “bohemian” flux that seeks out and reimagines a mix of the new, the derelict, and—like the Chase branch at 104—the newly derelict.

“The Real Estate Show was a cry of pain,” writes Moore.17 In those days, rising rent had pushed artists from their lofts in SoHo and TriBeCa; many landed in the cramped, sometimes illegal tenements of the Lower East Side. Yet the present situation in the neighborhood is closer to the rapid gentrification of SoHo in the 1970s than to the crusty, graffitied bohemia of the Lower East Side in the 1980s. “That world,” writes Moore,“is as much frozen in time and bound to a particular milieu as Greenwich Village or Montmartre.”18 Moore’s conclusion to his history of the Lower East Side gallery movement, included in Julie Ault’s Alternative Art New York reader, could easily refer to the Fuentes redux:

I made a sentimental journey to a vacant lot on January 1, 2000, the twentieth anniversary of the Real Estate Show. There, in a city-owned building, a group of artists had made a play for a piece of Manhattan action. On view that same day, up the street and around the corner, the fruit of that action, the cultural center ABC No Rio was exhibiting Dangerous Remains: Revolting Artifacts of the Premillennial Urban Infiltration Twenty Years after the Real Estate Show. Here I considered the wry captions beneath wall-mounted plastic boxes containing dusty dreadlocks, patchwork hotpants, and placenta prints from a homebirth, the obscure mysticism of hodge-podge construction work signified in cheery diagrams, and a box of “bugnuts” used to tap into electrical lines.… [T]his was an aestheticization of the experience of involvement in a resistance struggle.19

Indeed, the RESWT and the Fischer pop-up both played out against an almost rose-colored narrative of resistance to gentrification—if not of gentrification itself.

If the Fuentes site presented a sort of political art relegated to a more optimistic past, at RESx (The Real Estate Show Extended) (April 9–May 8), a sister show at ABC No Rio, the safe historicization of Lower East Side activism met the uncomfortable bleeding edge of the present version. Here, as with the original Real Estate Show, local artists were free to drop by and fix their works to the wall, often with tacks or staples, next to handwritten (often incomplete) title cards. Pieces included a glittered and marked recent real estate listing, anti-capitalist scrawls, and a set of steel tenements joined with a chain, by Julie Hair. Apart from its nod to ABC No Rio’s origin story, the show was in some ways no different from most others at the space. Organizers asked artists to bring art that could easily be replaced, since crowds press against the walls at weekly punk rock shows and readings. ABC No Rio retains the crusty, anarchic verve that stymies any review that would list the dates and titles of artworks.

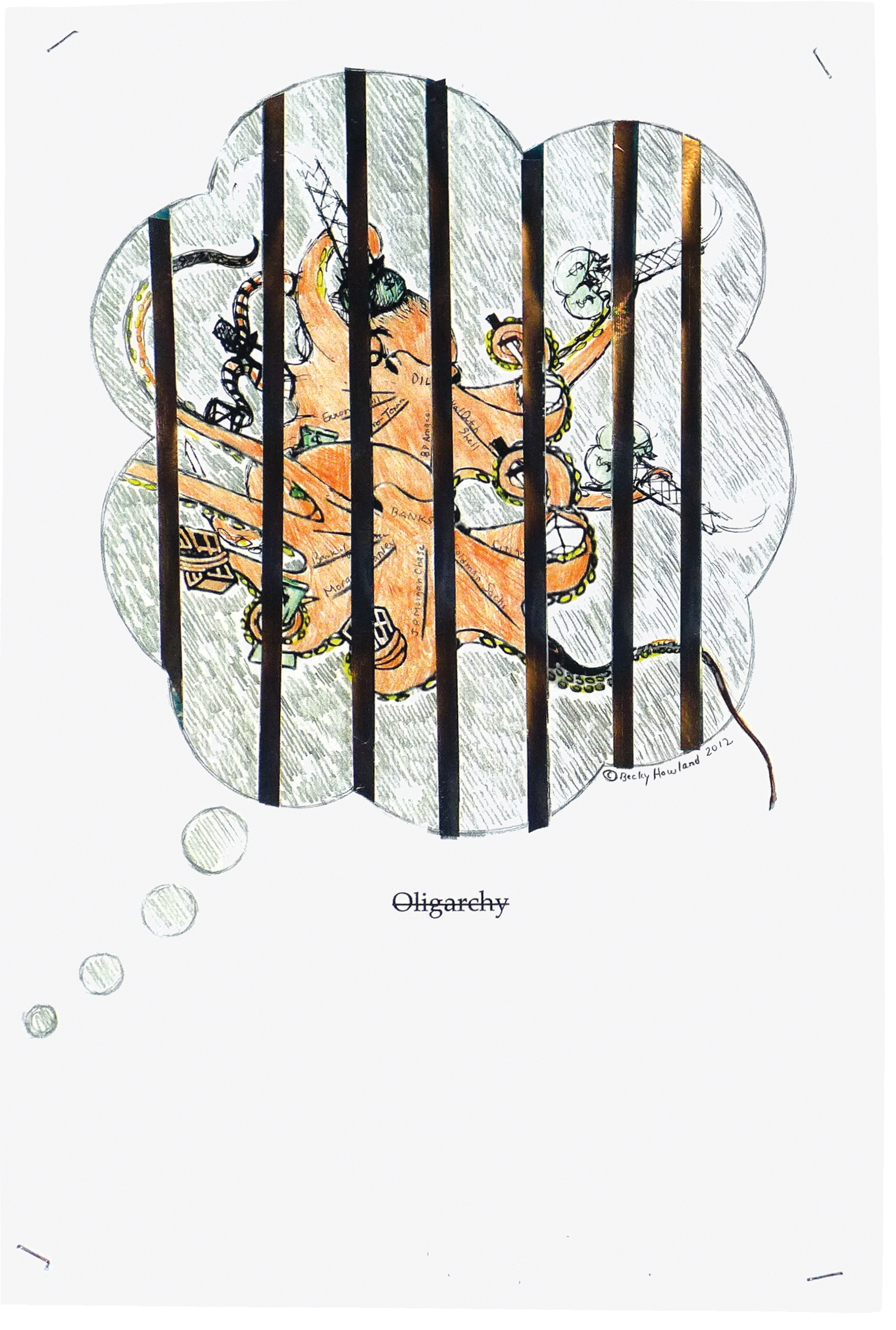

Becky Howland, installation view, RESx (The Real Estate Show Extended), ABC No Rio, New York, April 9–May 8, 2014.

All the same, these scrappy artists are presumably not without ambition, or a certain mobility. Of the early days of the space, Moore writes, “Artists at ABC No Rio led a double life, performing a sort of avant-garde social service experiment on the East Side while pursuing their individual careers as exhibiting artists seeking gallery representation uptown and in SoHo.”20 Two other venues held related, concurrent shows—organized in collaboration with James Fuentes and ABC No Rio, featuring many of the same artists—many of whom have since gained solo recognition. At Lodge Gallery, 131 Chrystie Street near the western terminus of Delancey, the exhibition NO CITY IS AN ISLAND (April 10–May 11) surveyed recent work from Colab artists, such as Tom Otterness, Ann Messner, Kiki Smith, and Joe Lewis, dealing more broadly with urban, social, and environmental issues. The Real Estate Show, What Next: 2014 (April 19–May 18), an installation at the small alternative venue Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, tucked into a stall at the historic Essex Street Market, served as a library of material on the SPURA development and its impact. The Essex Crossing plans, for example, include moving the entire market across Delancey into a larger new building. One exhibit there detailed the neighborhood’s forgotten sweet potato vendors of the early 1900s—another casualty of the city’s cycles.21 Writes Moore, “Thinking about The Real Estate Show now means thinking about occupation, which has once again become a focal tactic in the 2011 wave of global rebellions.”22 Yet the struggle for real estate has passed from ABC No Rio, secure in its hard-won space, to a gallery on the front line of the latest push.

Julie Hair, installation view, RESx (The Real Estate Show Extended), ABC No Rio, New York, April 9–May 8, 2014.

Mac McGill, installation view, RESx (The Real Estate Show Extended), ABC No Rio, New York, April 9–May 8, 2014

Brienne Walsh begins her review of Urs Fischer by observing that corporations like banks are typically the only businesses able to afford rent on Manhattan corners; the Chase branch at Essex and Delancey is case in point.23 Fischer apparently “played down the bank venue, saying he and the gallery had considered various spaces during a two-week search.”24 Nevertheless, it would be difficult to select a more charged symbol of the city’s decline and regeneration than an ex-Washington Mutual ex-Chase. Moore recalls the plans for the Lower East Side drawn up as early as the mid-1970s by the Trilateral Commission:

This high level group, commissioned by the Rockefeller Foundation, wrote an influential report recommending the total destruction of the barrio, and the replacement of the old tenement buildings with high rise Corbusier-style edifices. The way to achieve this destruction, it seems, was by allowing “market forces” to do it. These forces included “redlining,” a system whereby banks denied loans to anyone trying to start businesses or improve properties in the zone. In fact nearly all the banks had closed their offices in both the Lower East Side and East Village (east of Avenue A); they did not reopen until sometime after 2001.25

In the 1970s, New York faced bankruptcy; today, private interests such as banks are emerging from the recession streamlined and consolidated, ready for the next boom.

Rendering of the proposed future ABC No Rio building, 156 Rivington Street, New York. Rendering courtesy of Paul A. Castrucci, Architect.

In 2009, ABC No Rio officially bought 156 Rivington from the city for the price of $1. The collective is now close to raising the $5 million needed to construct a new LEED-certified building on the site to replace their crumbling tenement, potentially becoming—some four decades after their seminal occupation—a model arts institution.26 The RES, the original extra-legal art action, has stretched from one opening night to thirty-four city-sponsored yet willfully independent years. Operating from within, staging their own programming without any expectations for content or sales or the fame of their artists, ABC No Rio has anchored an activist art scene while the surrounding neighborhood has cycled back toward affluence.27 It would be too much to credit ABC No Rio itself with gentrifying the LES. Dozens of other spaces, both artist-run and fiercely commercial, pop-ups and media darlings, contributed to the trends that, like affection for his childhood streets, drew Fuentes back to Delancey. Indeed, whether motivated by cynicism or by desperation, their relative liquidity pushes artists to the vanguard of real estate politics. And there, on Delancey, both Fischer and the RES artists have demonstrated their sway—over context, over high and low, over real estate. The conduits of professional art allow for unique triangulations between the downtown barrio, the uptown gallery district, and back again. The challenge is to learn and/or profit from the inevitable clashes. Such disjunctions might make both art and buildings bankable, but may also be the key to keeping what’s rightfully ours. Abandoned safes stand open with the keys in the locks.28

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He is a 2013 recipient of the Creative Capital Arts

Writers Grant.