Mariah Garnett and William E. Jones’s experimental, research-based, and multifaceted practices are rooted in documentary filmmaking and critical engagements with archival sources. Their works explore unexpected narratives and complex histories that interrogate the role of the subject, the spectator, and the documentarian. Both artists also unapologetically and distinctly tackle sex and gender.

In anticipation of their two-person exhibition, The Long Take, which I curated at Los Angeles Contemporary Archive in the summer of 2016, Garnett and Jones joined me one hot Saturday afternoon in Los Angeles. We recorded our conversation while thinking through which of their video, photo, and archival works to include in the show. The conversation has been edited for publication. For more information and images from the show, visit: http://lacarchive.com/long-take-0. –Suzy Halajian

Suzy Halajian: How familiar were you with one another’s practices before this exhibition?

Mariah Garnett: I was pretty familiar with William’s work. In fact, he came to screen Fred Halsted’s L.A. Plays Itself (1972) in Thom Andersen’s class at CalArts, and I was the teaching assistant.

William E. Jones: I remember seeing your Peter Berlin piece with the film projected on the disco ball (Encounters I May Or May Not Have Had With Peter Berlin, 2012). I think that was the first time I had seen your work.

MG: I remember when you walked in, and you said, “Where did she get these old images of Peter Berlin?” If I ever had a DVD jacket for that installation, I would put that quote on the back.

WJ: You fooled me.

SH: You’ve both engaged with porn star Peter Berlin. Mariah, in the single-channel version of Encounters I May Or May Not Have Had With Peter Berlin, you attempt to embody Berlin as you reenact his poses in his signature style, and later on you actually interview Berlin in his apartment. And William, you include footage of Berlin in your 59-minute work v.o. (2006), which is composed of various segments of gay porn films produced prior to 1985. Was the initial impetus to delve into Peter Berlin’s world a nostalgic one?

WJ: The video v.o. came out of my experience working for Larry Flynt. I was producing a line of budget compilation DVDs—four hours for ten dollars—composed of scenes from old gay porn titles owned by Hustler Video. I was most attracted to scenes from movies that were shot on film, and consequently were of the most aesthetic interest. Two of the best were the Peter Berlin films. I have to confess that I don’t find Peter Berlin sexy as a performer. He interacts very little with others, because he’s most concerned with his own attractiveness. His work is an enormous project of self-portraiture, an expression of hardcore narcissism. For me, there’s no access there, but it allowed something to happen for Mariah.

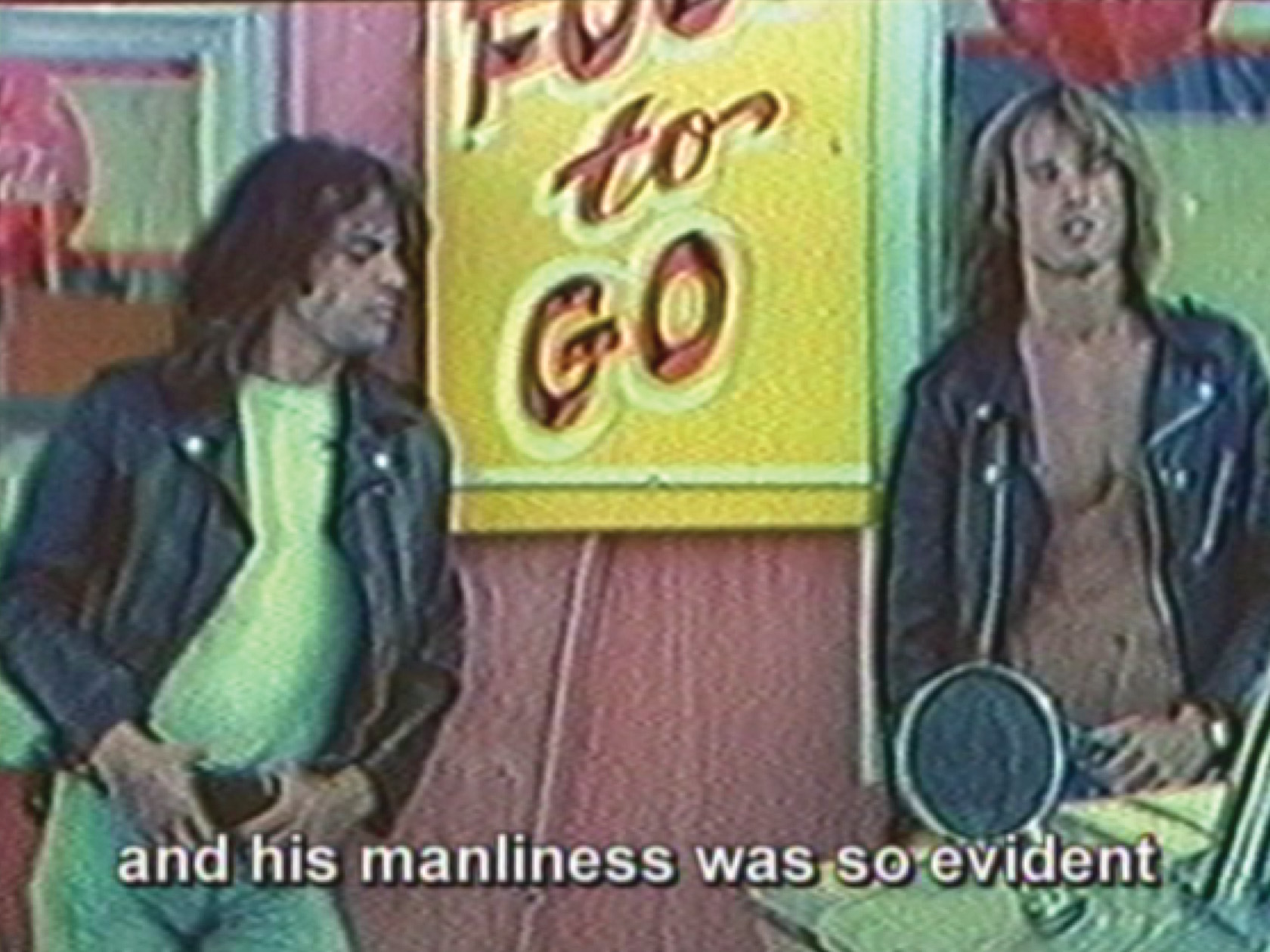

Mariah Garnett, Encounters I May Or May Not Have Had With Peter Berlin, 2012. Video still. 16mm film, color, sound, 20 min. Courtesy of the artist and ltd los angeles.

MG: The work was actually partially influenced by your work, because I was looking at pre-AIDS-era gay porn that has one foot in experimental film and one foot in this new genre that was gay porn, which had no real market yet. It was gay men making images for their own pleasure; there was no structure codifying how it was supposed to look. And then I came across Peter Berlin, whose films are so aesthetic, and something about the narcissism was compelling to me. Not in a sexually titillating way, but there was something about how earnest and un-self-critical it was. There was also the style that he’s completely fabricated, which is hypermasculine but also weirdly androgynous.

WJ: The pageboy haircut.

MG: Yeah, it was like discovering this person who is off by himself doing this little thing totally obsessively and generating thousands and thousands of images purely for his own pleasure. He didn’t parlay it into a financial career, really; he avoided the spotlight. He was doing it for his own self-gratification, and that played into this cliché narrative of what an artist is supposed to be: “I do it because I have to.” That’s not the way I make art.

WJ: Another aspect of your Peter Berlin work is that it reflects a radical change in women’s attitudes toward early gay porn. A few years ago, I gave a talk with Barbara Hammer, who came to prominence as a lesbian feminist filmmaker in the early 1970s. We were both a little apprehensive at first, but it ended up being a delightful event. She was really afraid that my work would have all these penises in it, and she wanted nothing to do with that. Women of later generations are embracing gay porn in its sexual explicitness.

MG: I guess there’s a fair amount of that now. It’s been re-appropriated by a younger generation. Maybe it’s because images of women, especially pornographic images of women, are so charged. It’s impossible to look at any images of women without them bearing some relation to sexism and exploitation. Gay porn effectively removes that problem—for women—and in that early gay porn, there is this sense they are doing it because they are turned on by it, which is hot.

WJ: I think it’s also that early gay porn stages something like pure sex in a way that people want to use for their own purposes today. This relates to my writing on Boyd McDonald (1925–1993), publisher of the first queer zine, Straight to Hell (1970s). Boyd collected “true homosexual experiences” like an anthropologist of smut. He wasn’t making erotica by transforming sex stories into literature, but rather presented the sex writing of a multitude of anonymous men in all its unadorned glory. His ideal, he used to say, was the graffiti in public toilets, which gets straight to the point. Some older gay men have read my work with a certain incomprehension. They’re not really sure why the subjects of my research are something special, because they were so much a part of the fabric of their daily experience in previous decades. On the other hand, almost all of the most positive reviews I’ve gotten for my book True Homosexual Experiences: Boyd McDonald and Straight to Hell (2016) have come from women who are a generation or two younger than I am, and that’s been very gratifying. I wonder why that is the case.

One way into Boyd’s project is through his film writing. He wrote wonderful essays on actresses. He saw them as often humiliated by an industry that transformed them into sex objects and oppressed them. For Boyd, the best actresses got through this with a sense of dignity by making wisecracks or perhaps by raising an eyebrow and subtly adding an extra dimension to frankly sexist material. They suggested subtexts of their own. This is very similar to what gay men of past generations were doing: they were taking old Hollywood films and using them as a mode of communication, a way of speaking in code to address someone who was clued in. In any given film, Boyd’s favorite performer wasn’t necessarily a glamour queen, and she wasn’t necessarily a “great actress” either, but she had a sense of humor about the situation in which she found herself. This kind of performer communicated in a profound way to gay men, who literally had no way of seeing images of themselves on screen. They couldn’t be explicit in their sexual interests unless they were with trusted friends or in a gay bar. They identified with these women who went after men but who couldn’t say they were just after cock—that would be pornographic—and they couldn’t be totally passive either, because that wouldn’t make for an exciting film. Both actresses in classic movies and gay men before liberation had to negotiate complicated restrictions on their behavior. It’s great that younger women have understood and appreciated this connection.

William E. Jones, v. o., 2006. Video still. Video, color, sound, 59 min. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery.

MG: Something that just came up for me when you were talking was about refusing this gender binary, which is built in to second-wave feminism and was the context for images of lesbians from that era. I know a lot of people don’t identify as women who love other women; they think about it in more abstract terms, and one way to do that is to look at gay porn. It’s gay, but you can, like you said, inhabit the body of another gender, and then perform these mental sex acts with the other person. It becomes really complicated conceptually, which is exciting, I think. It takes you out of being stuck in this gender binary. And it’s in line with what’s going on now politically, in terms of thinking about queerness and third-wave feminism being a reaction against defining what a woman is and identifying strongly as a woman.

SH: Mariah, how does your own physical appearance in films factor into this personal desire, for instance, with your performance in this work with Berlin? I’m also thinking about your recent work, Other & Father (2016), with your father. For that piece, you investigated the political landscape of Belfast in the 1970s, and also reenacted the original 1971 BBC news documentary that featured your father in an extremely controversial Catholic/Protestant relationship in Belfast. This was at the beginning of the conflict known as The Troubles, and it led to his leaving Ireland for good. We witness you reenacting your father in the documentary, next to Robyn Reihill, a transgender actress who plays your father’s girlfriend. Did your father end up seeing the project?

MG: Yes, he’s seen whatever I’ve shown of it thus far. His response is, naturally, wrapped up in his own experience of the past, and the way he was misrepresented by the BBC, so he was a bit miffed that, in my reenactment, the BBC narrative stayed intact. In making this work, my driving desire was to get to know my father better. In the video, I was re-enacting his desire, which was portrayed by the BBC, for his girlfriend. I cast Robyn Reihill partly because she’s a great actress but also because I wanted to map my own queerness onto this footage. If I truly was going to try to understand my father better through a reenactment of his adolescent love affair, my reenactment would inevitably be queer, and I wanted my casting choice to reflect that.

SH: Mariah, did you have a clear plan when you went to Ireland to make Other & Father, or was it more of an attempt to spend some time wandering around in Belfast and see what happened?

Mariah Garnett, Other & Father, 2016. Still from two-channel video installation. HD video transferred from 16 mm, color, sound, 11 min. Courtesy of the artistand ltd los angeles.

MG: Initially, I was going to go stay with my dad (who no longer lives in Ireland) for six weeks, and I didn’t really have a clear plan. I knew I wanted to make this project about him and about his history in Belfast. I had found this archival footage of him and brought it with me. I knew I wanted to document us interacting, which was really difficult to do because I didn’t have a cameraperson. It was also really hard to navigate when to turn the camera on and when to turn it off. I think I made it a much bigger burden than it actually was. I had always planned on going to Belfast to look up his old street and check the city out, and maybe look up one of his brothers or sisters in a phonebook. I imagined I’d be there a week; it turns out that just my initial idea took two months, because it’s so confusing there. On the first trip, it took several attempts and multiple government agencies before I found my grandmother’s grave. The first time I tried, half the gravestones were knocked over, and all the graves were overgrown. It was not a well cared for cemetery, it seemed like evidence of massive death, with the anxiety around it and a desire to forget. I would’ve expected an Irish cemetery to be quaint and mournful, but this was like deep trauma. And there were drunk guys in tracksuits hopping the fence and pissing on the gravestones. I was there alone, and I was kind of scared, actually.

SH: That’s quite a crude introduction.

MG: I did eventually find her, but her grave was unmarked, and I had to go to the cemetery office. Turns out there are two other people buried with her. Everything there is more complicated than you would expect. All of the old streets in my dad’s neighborhood are gone. It’s hard to pinpoint where the old street even was, where his school was. The city has changed and been reorganized so many times since the 1960s. Simple tasks like that become really, really difficult.

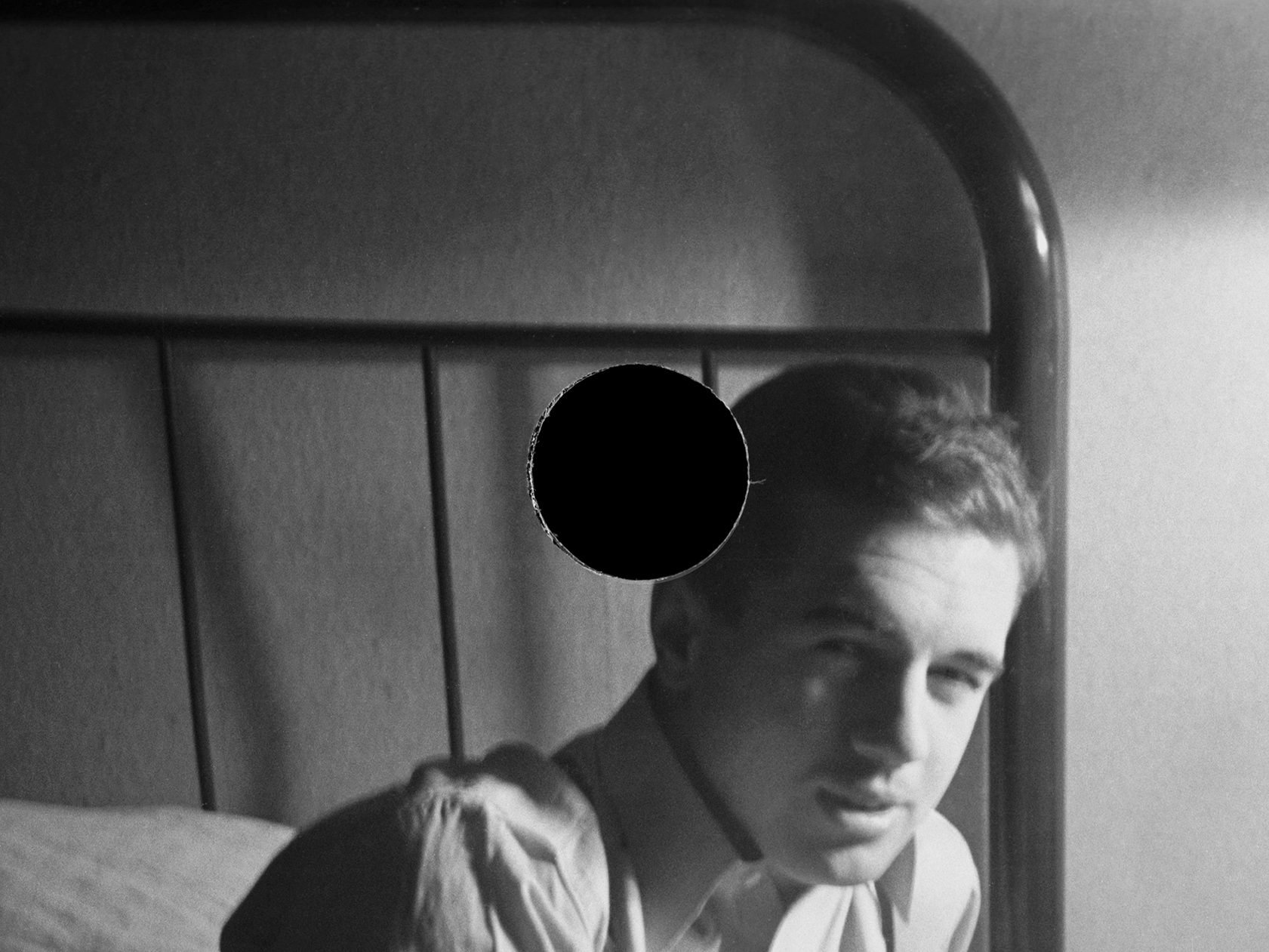

SH: It seems that, with both of your practices, you enter into a process, often through archival research, thinking that the work will land one way. But the material you encounter opens up multiple narratives that then shift the work. William, for example, with your 2009 film Killed, which first introduced me to your work, you were looking for examples of gay life in the Library of Congress’s FSA archives. The punctured images you encountered in the archives led to a different kind of project.

WJ: I was looking for something very subtle. Using the phrase “gay life” is already going farther than the subjects of these photographs would go. Nobody having a “fairy party” would have allowed a government photographer to come in and take pictures. At that point in the United States, it was illegal to have a single-sex gathering of more than two or three people. Even private parties got busted.

SH: This is when?

WJ: The 1930s through the early 1960s, perhaps even later in some places.

MG: Could straight men not have parties with all guys then?

William E. Jones, Killed, 2009. Video still. Sequence of digital files, black-and-white, silent, 1:44 min./looped. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery.

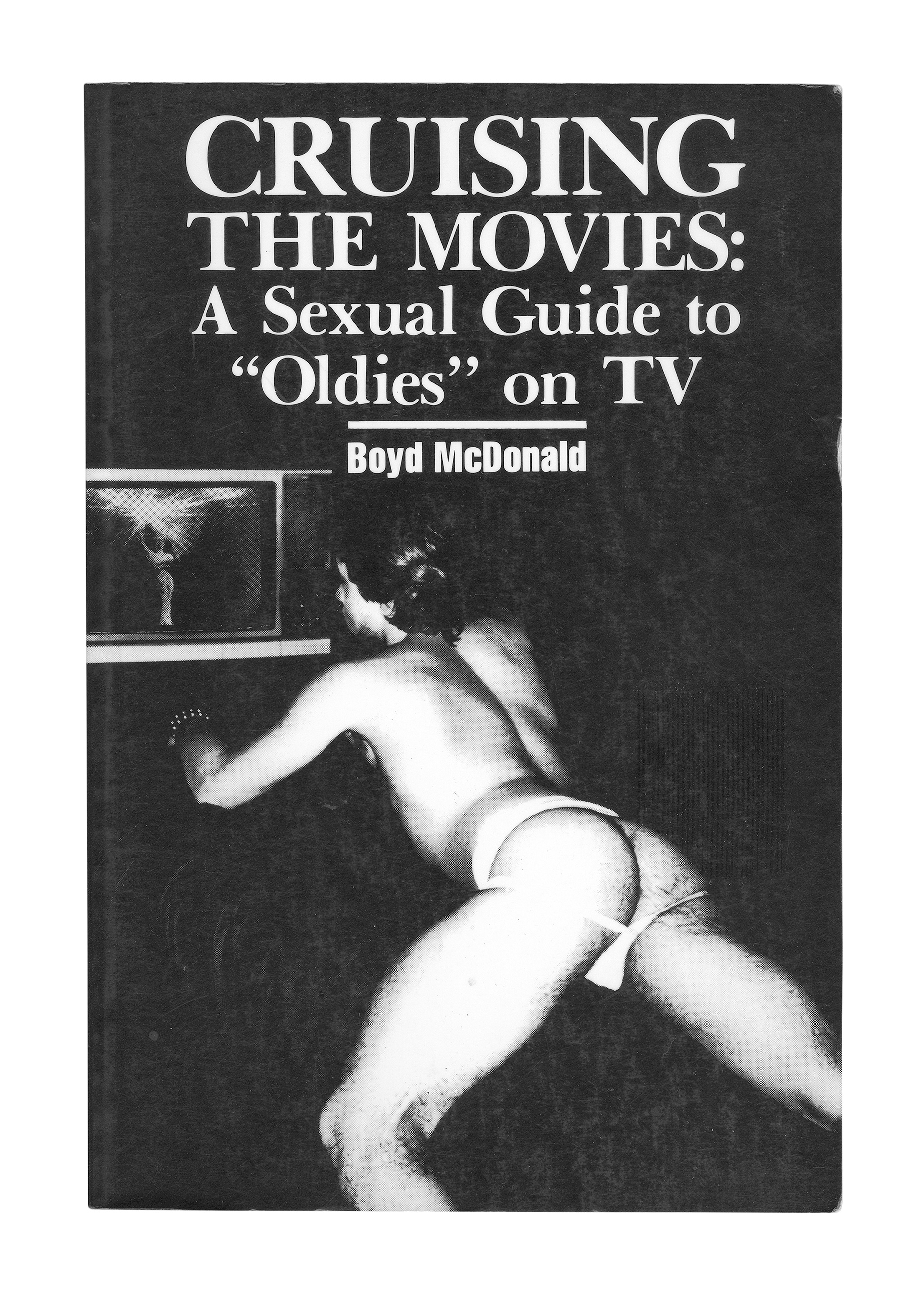

WJ: There’s clearly a double standard. Nobody was busting baseball games. This is the situation that Boyd McDonald described: being gay and totally surrounded by these all-male groups that were homoerotic, yet no one was saying a word. The main object of his wrath was hypocrisy. Boyd constantly ridiculed professional sports, the military, and the mass media. In every newspaper he read, he was looking for instances of hypocrisy, especially those denigrating queer people. He wrote satire, and it’s hilarious. For instance, in his book Cruising the Movies (1985), Boyd writes about Ronald Reagan appearing without pants in a movie and says he looks like a butch lesbian. For a femme lesbian, he uses the word “fluff.” He doesn’t explain, he just remarks, “Patricia Neil’s fluff in this film is Lizabeth Scott.” This casualness reflects his simply not giving a damn about the standards of conventional society. It’s such a refreshing attitude, so salutary for thought.

SH: How were you first drawn to his work? Did you find a copy of the magazine?

WJ: The first thing I gravitated to was Cruising the Movies. I had studied film, and I was interested in someone who wrote about films in a way that was not pious. Boyd had nothing to do with academic film theory, but he was smart, and he engaged with issues that were well beyond what one would expect from a book with a guy’s naked ass on the cover. Boyd wrote very well, but he was not interested in participating in mainstream intellectual life. He preferred to be an irritant, the one who says, “Oh, but wait, all you people are lying.” There are lies we mutually agree upon so that we can get ahead in this world, and he wanted no part of them. Boyd lived on welfare in a single-room occupancy hotel, so he had nothing to lose. He could call anyone out on their hypocrisy. I’m most interested in people who occupy a position in the world that is despised and not respected, yet who do something that is artistically or intellectually compelling and speaks to the situation of the world. The people making the most decisive and thorough critiques of society do it from a position of no status whatsoever. They’re not trying to get tenure; they’re not trying to be published in a national magazine; they’re not trying to be on television or to be recognized as a public intellectual. They come from nowhere and they say something shocking, and it is simply on the strength of what they say that they convince; they’re not relying upon the authority conferred by status or association to make their argument.

SH: Has the desire to get closer to specific subjects driven your projects? For example, in William’s films and texts, subjects have included artist/filmmaker Fred Halsted, the cult band Morrissey, Finished (1997) porn star Alan Lambert, and, recently, Boyd McDonald. And Mariah’s work has engaged with distinct subjects, such as US war veterans who work as Hollywood stunt men, in Full Burn (2014), and Catalina de Erauso, a nun turned conquistador from the sixteenth century, in Picaresques (2011).

Cruising the Movies by Boyd McDonald. (Gay Presses of New York, 1985). Courtesy of William E. Jones.

MG: I use filmmaking as a way to connect with people who I wouldn’t really be able to connect with in regular life. For example, with the veterans, that drive was pretty strong. They’re not in my social circle, but I have a lot of military men in my family, none of whom I ever broached the subject of war with. The film was a way of understanding something about them that I was interested in—that they would come back from being under constant threat of bodily harm and then volunteer to essentially reenact that scenario in their work life. I wanted to know if this was a way of dealing with trauma, or if it was a personality type that gravitated toward the military, or if it is just an extreme by-product of capitalism. I’m really interested in people who obsessively do something that could be viewed as outrageous or outside of the norm. A lot of the time it doesn’t have to do with prestige or money. For example, one of the reasons I was drawn to Peter Berlin is because his interest in this thing was so pure and his output so prolific. He continues to do it in a vacuum and doesn’t show anyone—he has a dresser full of Hi8, VHS, and MiniDV tapes no one has ever seen, and I imagine he’ll do it forever, whether anyone sees it or not. This is the type of person I’m interested in. What is the driving impulse? Why do you keep doing that?

WJ: There’s always a problem of legitimacy. Most of what passes for literary criticism in the United States is really just a veiled statement of class prejudices, a variation on “This person is not a real author because he didn’t go to an Ivy League school, or he didn’t go to an MFA program.” I have absolutely no interest in that kind of status mongering. The first chapter of my Boyd McDonald book is called “An Improbably Literate Hustler,” a phrase I found in a successful (and conventional) gay biography. To me, that phrase is redolent of prejudice. Why can’t a hustler be literate? Now, we must admit that a hustler is allowed to be literate in a different way than a graduate of an MFA writing program is, but why do we respect one more than the other?

Unfortunately, the risk you run when you choose as a subject somebody who is an outsider, who is really idiosyncratic, is that people won’t take you seriously. It’s a form of non-discursive, naïve criticism, implying, “This person isn’t worth writing a book about.” It’s a complete disregard of argument and of the aesthetic force of the subject’s work. It’s merely an assertion of status, but it carries weight in this common world.

Mariah, something you said really interested me. In making films, you are getting access to people you would not necessarily see in normal life. It reminds me of what queer life used to be, a way for people of different social classes and different ethnic groups to mix, to have intercourse—not just sexual, but social. Someone of a very elevated social class could be dating working-class partners, and people of different ethnic groups could be together, because they were equally despised by mainstream society. They were all outlaws. With gay liberation, and now gay marriage, that’s something that is getting lost in our society. We are being encouraged to cultivate a mentality that was once associated with suburbia, even if we live in a city, by adopting conventional attitudes for “safety.” Nowadays, there’s a lot of talk about multiculturalism, but in a certain way, our society is actually becoming more static, and the social mixing of people, especially across class lines, is becoming very difficult. For instance, as educational institutions become more expensive and more exclusive, we’re seeing less of what education used to be about—people from different backgrounds fucking and having fun and learning from each other. Those are important lessons. This reminds me of the utopian possibility in Tearoom (2007), which consists of surveillance footage shot by the police in the course of a crackdown on public sex in the American Midwest. You see black men and white men together, men who were clearly working-class with guys who were wearing business suits. They were fucking each other, but they could only do it underground, literally underground—the sex the police documented took place in a public toilet under the central park of Mansfield, Ohio, in 1962.

William E. Jones, Tearoom, 2007. Video still. 16 mm film transferred to video, color, silent, 56 min. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

SH: Yeah, but you weren’t meant to ever see those interactions.

MG: That’s one of the weird things about the internet. The paradox is that it has supposedly destroyed all the barriers that necessitated these underground spaces to exist in the first place, and consequently, those spaces don’t really exist anymore. So there is less social mixing in real life, less interest in other people, and the internet is starting to reflect that. What’s emerging is this impulse to barricade yourself into a group of people who agree with you or fight viciously with those who disagree. I know I do it (the barricading; I avoid the fights). But in reality, I don’t always want to be around people who think just like I do.

WJ: A chance meeting with someone you didn’t expect have anything in common with, but with whom you share something important, is a thrill. That’s something very precious, and I wonder if it’s getting lost in the present era.

MG: That thrill is definitely one of the biggest impulses behind making work for me.

WJ: It was certainly one of the motivations behind my documentary Is It Really So Strange? (2004). I’m a first-generation Smiths fan, and I bought those records when they originally came out. I wanted to see what kind of conversations I could have with fans who were much younger than I am and mostly Latino. It was really wonderful to speak to them and to interact around questions that we all cared about. My original plan was for a narrated film. I recorded about an hour’s worth of voiceover. Then I started interviewing people, and the whole project changed. Basically, my rule of thumb was that every time an interview subject said something that overlapped with my narration, I would remove it from my narration, so I cut my share of the film to about 15 or 20 minutes. I gave the floor to the people I was interviewing. That was a liberating gesture. It was wonderful to get other points of view from people recounting their experiences in a very intimate space, often their bedrooms. How can I put their contributions into a proper context? It’s an important ethical question for a documentarian, and a responsibility that you shouldn’t turn away from.

Suzy Halajian is a curator and writer based in Los Angeles.

Mariah Garnett is an artist and filmmaker known for her filmic portraits that combine multiple cinematic strategies to locate and codify identity. She is currently working on her first feature, Trouble.

Fall into Ruin, William E. Jones’s new film about art dealer and collector Alexander Iolas, premieres this year in solo exhibitions at The Modern Institute, Glasgow, U.K., and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.