Conversations expand and contract, circling, like detritus cast up on a stony beach—a bright piece of plastic rope, a broken board, a small shoe. The waves repeat, sliding over the stones, leaving “scraps, orts and fragments” behind.1 This repetition exceeds our description, like the conversations circling, and leaves me with a heap of remnants, disparate yet connected, some thoughts on repetition.

The first conversation was a written exchange with Francette Pacteau, who said something like: Photography is no longer a discrete category, it suffuses us; it’s everywhere, inside and outside us, consciously and unconsciously… Or that’s what I thought she said.

Actually, she wrote this, in an email from Paris one morning: “It is in our every bone, as it were, ‘it’ has dissolved into a multitude of practices—conscious and unconscious—it has shaped our sensibilities, the ways we see the world and ourselves in it, etc.” In which case, we can’t say: Here I am, and there is the thing, and there, on the other side, is the image, the photograph of the thing. We can’t draw such distinctions.

Later that day I spent some time with an artist from Iceland, Páll Haukur. In response to this notion that photography is not a category, he said something like, Yes, this is what I have been saying: There is no medium. He said he thought a new philosophy would emerge, in response to our contemporary being in the world. At one point he said, memorably, There is no representation. As if the idealist, Platonic infrastructure has finally collapsed under the pressure of our multifarious interconnected and apparently immaterial screens.

Páll and I went together to see what can only be described as an exploitation documentary, Let Me Die a Woman (1977), which was made across a number of years in the 1970s by Doris Wishman. One of the most prolific women filmmakers of the twentieth century, Wishman is admired in certain circles for her films Bad Girls Go to Hell (1965), A Night to Dismember (1983), and Dildo Heaven (2002), a film she was working on at the time of her death at the age of ninety. Let Me Die a Woman purports to be a documentary on what it calls transsexualism. It is truly unsettling, hilarious, and shocking, and includes close-up footage of an actual sex-change operation, as well as ethnographic displays of the naked bodies of male-to-female trans people. In these scenes, the subjects stood calmly before the camera in what appeared to be an elaborately staged medical examination room, their hands gently clenched by their sides, as the doctor used a collapsible metal pointer to emphasize specific physical characteristics.

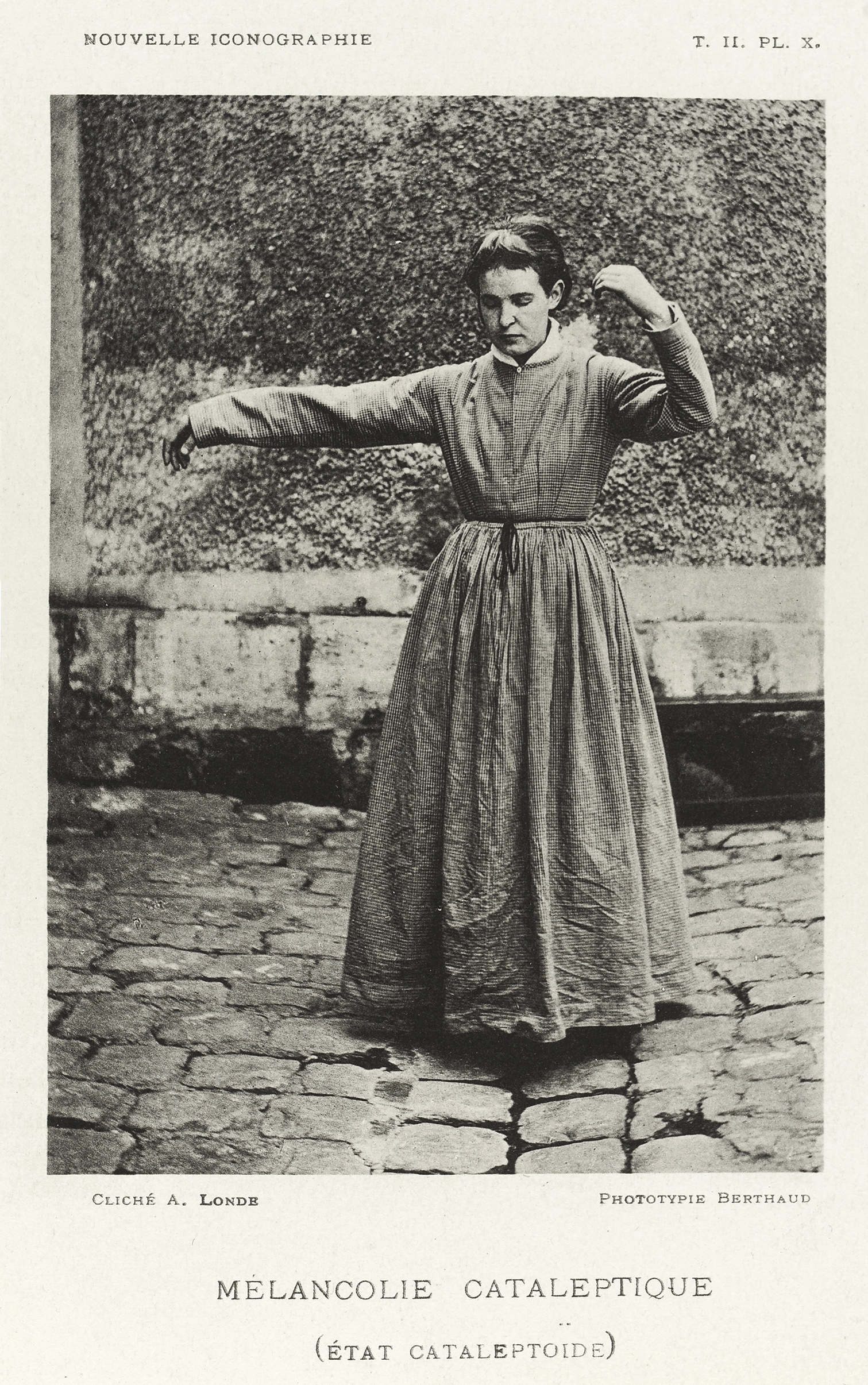

Albert Londe, Mélancolie cataleptique (État cataleptoïde), from Jean-Martin Charcot et al, Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière; Clinique des Maladies du Systeme Nerveux (Paris: Lecrosnier et Babe, 1889), vol. 2, plate 10. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London.

It was striking to hear how emphatically these pioneers in the field of sex-change surgery insisted on their need to become “a complete woman”—a category that was itself undergoing deconstruction in the discourses around feminism and psychoanalysis at the very same time. The completeness they invoked was defined by certain socially agreed upon attributes and activities, certain practices that could apparently guarantee and validate a specific gender identity. The task was to match reality to the image, in an aspirational push towards an impossible ideal. I would argue that these aspirations belong to the very structure of femininity, and are therefore shockingly familiar.

The artist Zackary Drucker presented the film, in the context of Queer/Art/Film—L.A., a film series presented at Cinefamily and curated by Lucas Hildebrand. Zackary’s work is imbued with her interest in queer and trans history—a history that is hard to trace and therefore precious, whatever form it takes. Let Me Die a Woman presents its trans characters as specimens, to be scrutinized within a medical frame, but it also implicitly allows us to wonder at the motivations of the individuals who were willing to undergo the objectification of that frame, in order to achieve a presence, as representation, for unknown others—for us, in the future.

At the end of the film there was a Q&A, and someone spoke of a recent conversation about a trans acquaintance, in which someone else had said how unfortunate it was that this mutual acquaintance wouldn’t or couldn’t pass. They wondered if the ideal of passing as a specific gender was somehow all wrong, or out of date, or limiting? From the stage, Zackary smiled and said, “Yes, I think nobody passes.” In other words, whatever our struggle, we all fall short and at the same time exceed the limits of the image, that ideal image that promises a control and a completeness that will always elude us.

Páll Haukur described it in these terms: Photography (or gender identity) is not “post-descriptive” so much as it is constitutive, as we strive to imitate an ideal, to repeat it and copy it, in a performance of identity and belonging. I’ve been fascinated by Lacan’s essay on the Mirror Stage for a long time now, and it seems to me to be the fundamental text on this question of our relation to the (ideal) image.2 Ideal is in parentheses there, because in a sense all images are idealizations. Lacan is clear that the relation to the mirror image produces an idealized version of the child, who sees something he mis-recognizes as himself: the mirror presents a child with a complete outline, exteriorized, framed, and perspectivally situated within a virtual, that is, fictional, space. The child points to the two-dimensional image, symmetrically reversed, incomplete in so many ways, and says, That’s me! Ever after, our task will be to try to line up that image with our own lived real. That impossible project—and the contradictions that ensue—is what we all live out, every day.

We want to be like the mirror, but we’re all over the shop; we’re more like sculpture than we are like pictures. We’ve got backsides and insides, and we see everything from an interior that mixes up whatever we see with memories and fantasies and other images and wishful thinking of all descriptions. Lacan says the mirror image provides the child with a model, a prototype for objects in the world.3 In a sense, we aspire to become like an object, complete, coherent, and seen from the outside, and failure is built into that project from the beginning.

Lacan’s description of the child in front of the mirror raises the question of what happens when the mirror is itself both de-stabilized and mobilized, becoming a disparate collection of different sized screens, multiple windows framing the world in a series of temporary, arbitrary articulations. In a doctor’s waiting room in Los Angeles recently, I saw a child of perhaps three scrolling through the videos on her mother’s phone, adroitly using the touch screen to select which one to watch. They were videos of the child herself, on her tricycle, at the beach, etc. She staved off the boredom of immobility by the fascination of watching herself repeated, perpetuated, watching a repetition of movement, exteriorized. Did she remember the internal sensations of the experiences depicted? Or was the detour through the image complete, the girl watching herself as another might?

Paul Regnard, Attaque: Période Épileptoïde. Planche XVII, from D-M. Bourneville and P. Regnard, Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière: Service de M. Charcot (Paris: V. Adrien Delahaye, 1876–80), vol. 1, 1878. Albumen print. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London.

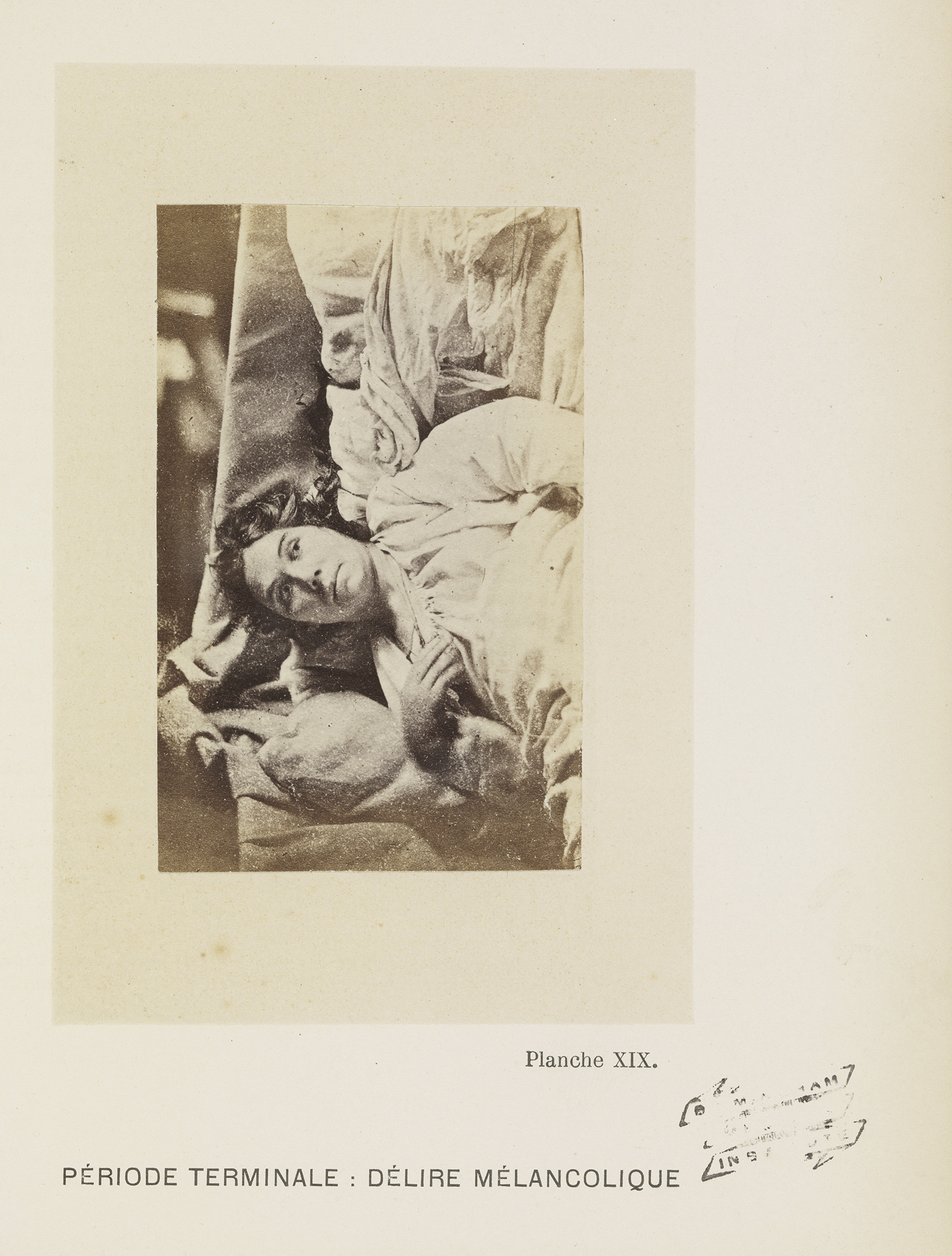

Paul Regnard, Période Terminale: Délire Mélancolique, Planche XIX, from D-M. Bourneville and P. Regnard, Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière: Service de M. Charcot (Paris: V. Adrien Delahaye, 1876–80), vol. 1, 1878. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London.

Lacan proposes a connection between the structure of the mirror and our fascination with statues, ghosts, and the automaton, in which the world of our own making (our human world) tends to find (as he puts it) completion.4 When I think of the automaton, I remember the Terminator, with his ambiguous promise of eternal return: “I’ll be back!” I think of the vampires: Miriam Blaylock, Angel, Spike; I think of Seven of Nine, the cyborg on Star Trek: Voyager, and the last Time Lord, aka Doctor Who.5 We are fascinated by these figures in part because they live both inside and outside time. They cannot die, and as such they are more like that mirror image, the mirage (miroir/image), than we will ever feel ourselves to be.

More recently I’ve been watching a brilliant TV show called Orphan Black, in which a young woman accidentally discovers that she’s a clone, a scientific experiment, and one of a group of identical yet very different young women: the pill-popping uptight suburban housewife, the brilliant lesbian genetic researcher, the extremely violent punk psychopath, the New York City cop, etc.6 (One actor, Tatiana Maslany, plays all of them, needless to say.) Cloning is about repetition. We like thinking about human clones because we enjoy the play of similarity and difference, the question of how to become individual, the question of duplication. And we like to consider those who are almost human, the hypnotized, the pre-programmed—Trilby, River in Firefly, Echo in Dollhouse—because they present for us the conundrum of the unconscious.7 To some extent we are all pre-programmed, according to Freud, driven as we are by the secret contents of our own inner cabinets of curiosity, the unconscious system.

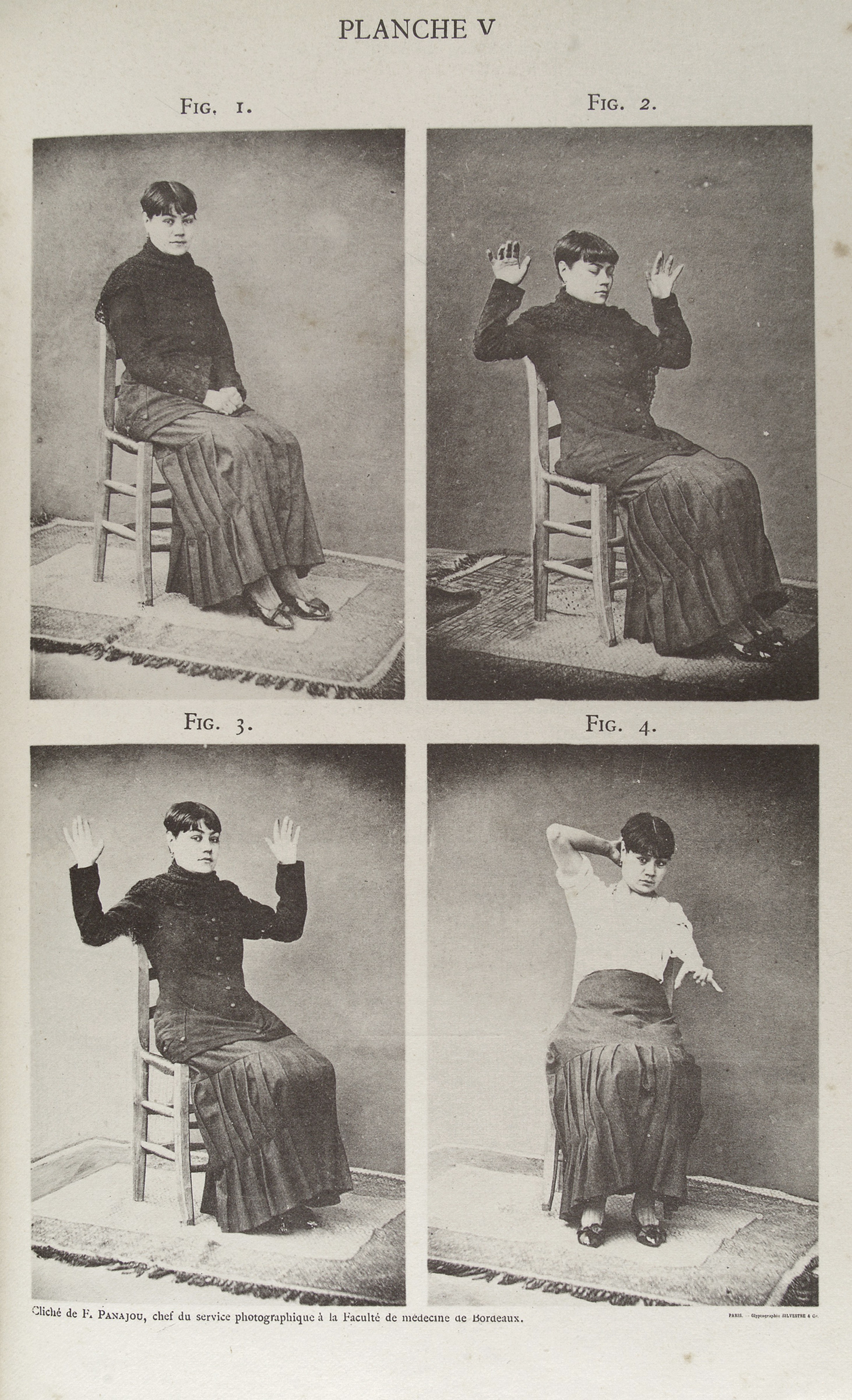

F. Panajou, Planche V: 1. The patient awake; 2. The patient in a cataleptic state, eyes closed; 3. The patient in a cataleptic state, eyes open; 4. Visual hallucination during cataleptic state, from Albert Pitres, Leçons Cliniques sur L’Hystérie et L’Hypnotisme (Paris: Octave Doin, 1891), vol. 2, p. 523. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London.

The vampire, the automaton, the clone, and the hypnotized: all of them are both human and non-human. There is something mechanical about them, as by definition machines are repetitive. Ideally, they repeat perfectly, you can count on them not to fail. Jean-Martin Charcot’s Augustine could be counted on to perform hysterical seizures on cue, before the public at his leçons du mardi, and before the camera in the photographic studio at La Salpêtrière.8

These things, the automaton and her friends, are more like a photograph than they are like me. They are exteriorized; we don’t see the connection between inner motivation and outer behavior, because the programming is alien to them. Most importantly, machine like, they appear both dead and alive, a paradoxical state to which I too unconsciously aspire. For I am locked in repetition, in a death sentence that requires me to be myself, to go on being Leslie Dick, day in and day out, until death, or another unlooked for catastrophe, interrupts the repetition.

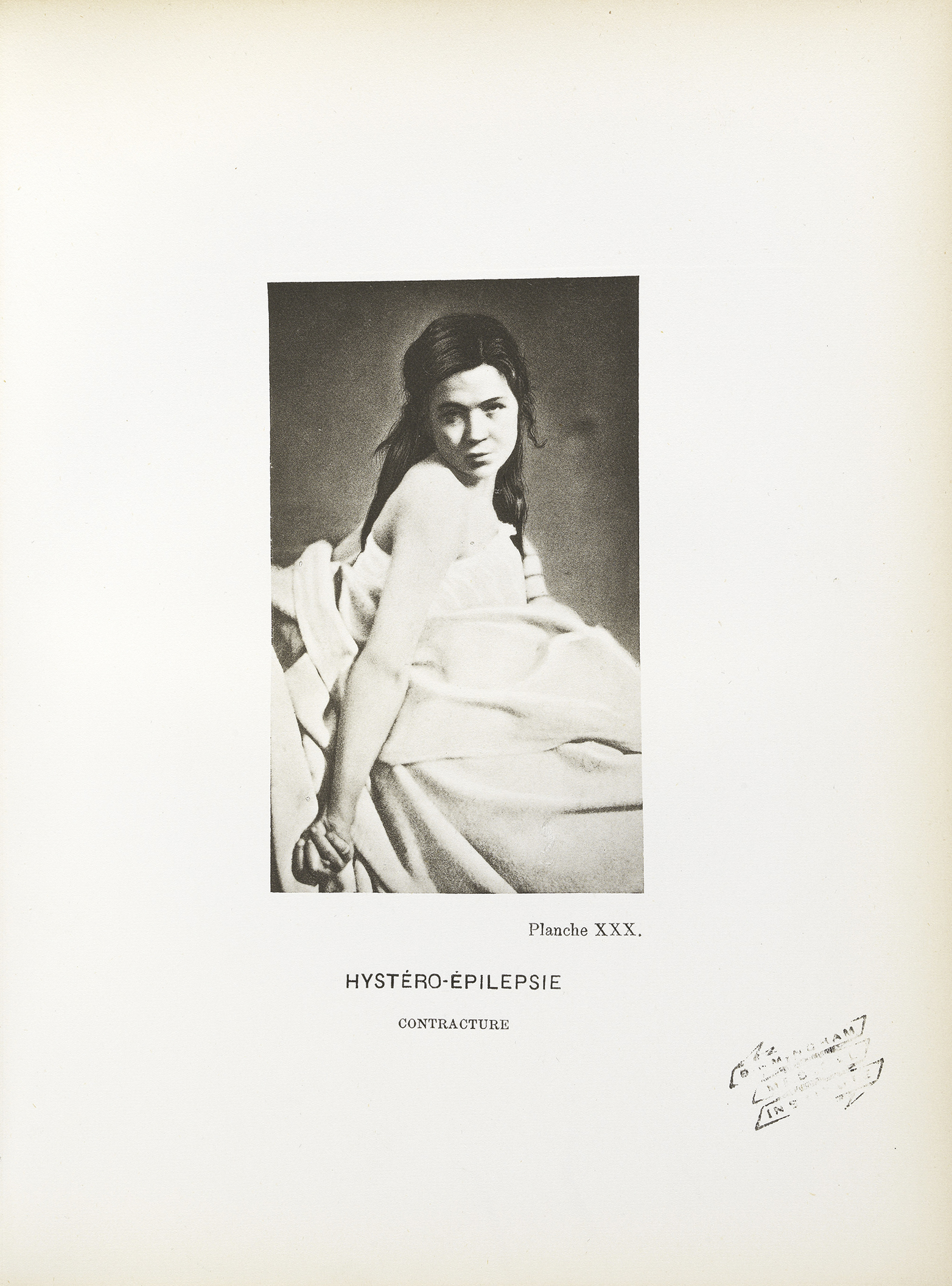

Paul Regnard, Hystéro-épilepsie. Contracture, Planche XXX, from Désiré-Magloire Bourneville and Paul Regnard, Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière: Service de M. Charcot (Paris: V. Adrien Delahaye, 1876–80), vol. 2, 1878. Collotype. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London.

I have a limited repertoire, of gestures, vocabulary, ideas, lipstick, and it is through repeating them with a kind of dogged persistence that I become recognizable, to myself, to you. I repeat myself, endlessly. The symptom by definition must be repeated, in order to be recognized as a symptom—otherwise it would be merely an untoward event. In this sense, to be myself, as I am constantly told I must, is symptomatic.

There’s more to this. It is through repetition that we perform the work of mourning; we go over and over the ground, re-living in memory scenes that are forever lost to us, yet indelibly present in our minds. Freud proposes melancholia as a refusal to do this work: we set up the lost object inside ourselves like a monument, a memorial, in perpetuity.9 Recently I met someone who told me that she and her dear friend had realized that they were carrying the dead corpses of their ex-husbands around with them, so that the stench, the stench of the rotting corpse, would keep other men away. She told me they realized they had to do what she called “burning rituals”—and then she told me the stench lifted, dispersed in the smoke rising into the night sky over Los Angeles. Keeping someone dead and alive allows a kind of stasis, where neither you nor I have to move, shift, change. To let go is to open up that space, to let something other in.

Sometimes we get stuck on repeat. Freud is clear about it: There is no time in the unconscious.10 I guess that means there’s no repetition, and there’s only repetition, because nothing erodes or fades, everything remains, as bright and hard as the first time. Time is both lost and found in the photograph, as it presents a moment definitively past, yet perpetuated, stilled and captured. Repeated.

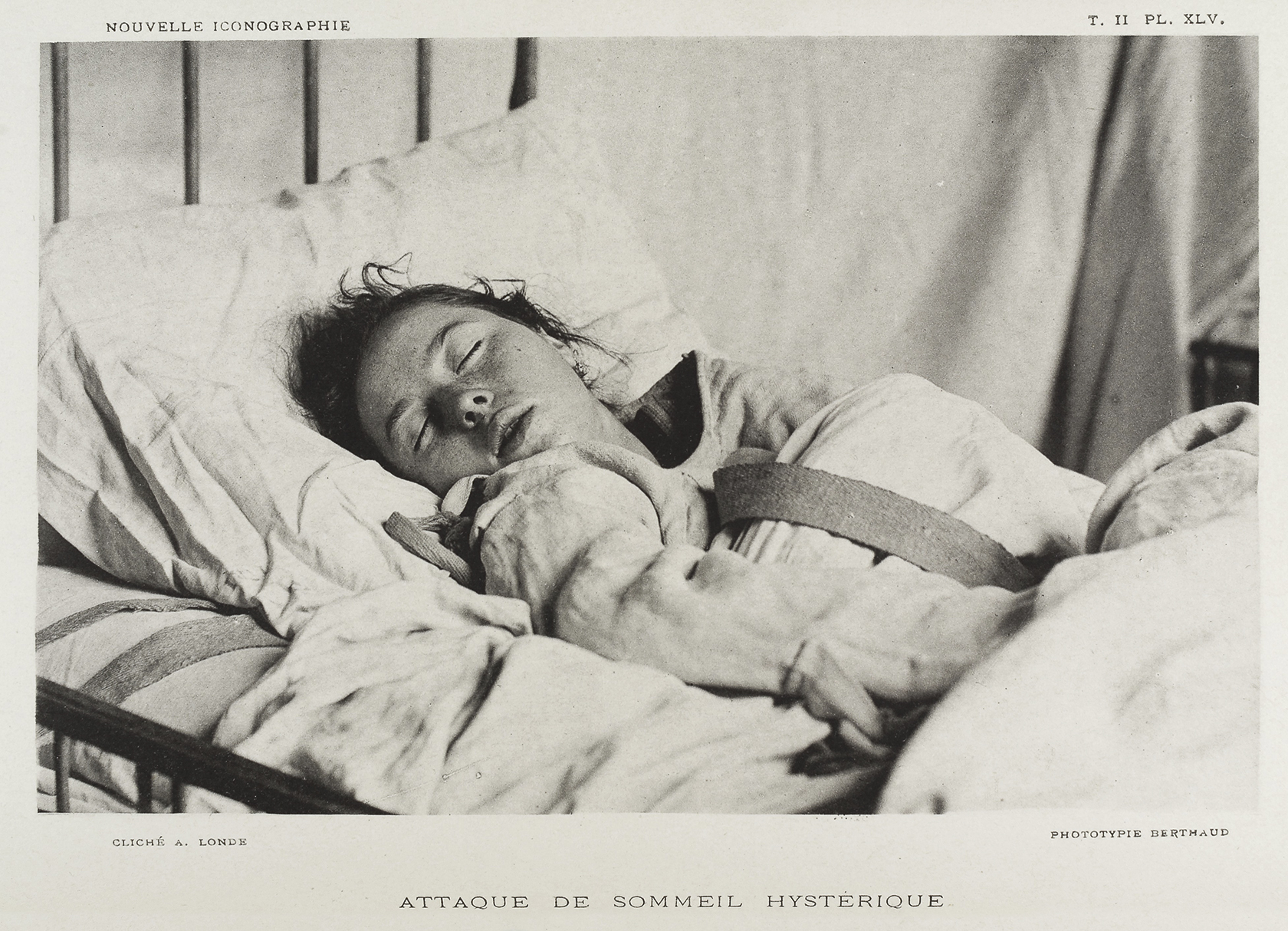

Albert Londe, Attaque de sommeil hystérique, from Jean-Martin Charcot et al, Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière; Clinique des Maladies du Systeme Nerveux (Paris: Lecrosnier et Babe, 1889) vol. 2, plate 45. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London. Note the straitjacket.

When the child watches herself running around in miniature on her mother’s iPhone, she is watching a former self, even if the video was shot that very day. It’s a repetition, not only in re-viewing the footage, over and over, as she might ask for the same story to be read to her over and over again, but also in her imagination she can perhaps relive the scene in the garden. At the same time, this tiny child knows she can use the device to make a new film of herself, here and now, or merely to fix her gaze on her own live reflection, as people do to check their hair, or their lipstick.

Is the child with the phone carrying the dead corpse of her own repetitions around with her, so that the stench prevents something else, something other, coming in? Roland Barthes wrote that the photograph was attached to the real like a criminal chained to a corpse. He said the photographic image literally drags a rotting corpse around with it—the pre-text, the real thing, the event.11 Maybe now the connection to the real is breaking, and the corpse can rot away…and turn to dust.

The idealized image produces endless repetition, a copy of myself, an illusion of mental stability and coherence. When the photographic paradigm is undone—by digital technology, among other things—the corpse can fall to pieces, come apart, as the real event dissolves into uncertainty, and all the framing devices melt into air.

Nobody passes, despite the apparently infinite repetitions of the digital, as the image becomes inconsistent and cannot be measured against a preexisting reality. Nobody passes, and with that we can perhaps move beyond ideals of control, completion, and totality, to a space of uncertainty that is both impossible and beautiful.

Leslie Dick is a writer who teaches in the Art Program at CalArts. She is currently a visiting critic in sculpture at Yale.

An earlier version of this text was presented at Returning to Berlin: a symposium on photography and repetition, organized by Kim Schoen, at MOTTO, Berlin, on August 11, 2013.