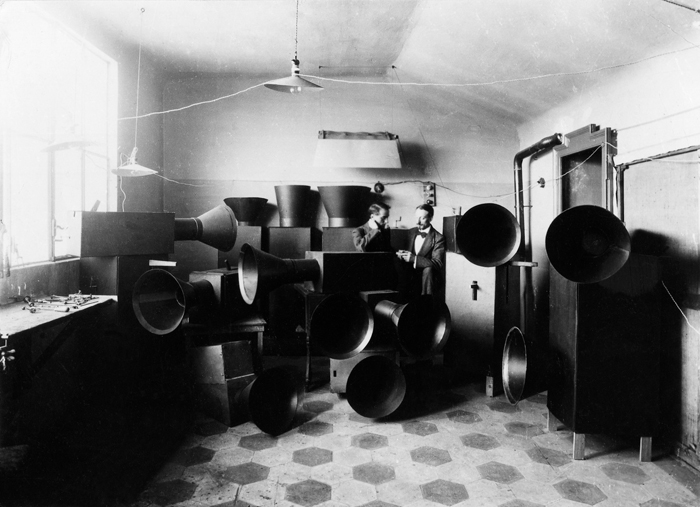

Luigi Russolo (right) with his assistant Ugo Piatti and their intonarumori, 1913. Courtesy Rovereto, Mart, Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Russolo.

I. A Photograph Comes to Life

In every history of sound-art lurks a photograph of the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo (1885-1947) and his assistant in Russolo’s painting studio with the intonarumori. Literally noise-intoners, these were musical instruments with delicious names: gorgoliatore (the gurgler), ululatore (the howler), stroppicciatore (the rubber), and so on. Played with levers and cranks, and housed in simple plywood boxes, the intonarumori channeled their gurgles and howls through large, speaker-like cones. Much in the photograph is obscure: the bulky boxes hide the internal mechanisms from view, and both the photographer and the precise date of exposure are unknown.

In spite of or perhaps partly because of its obscurity, the image has become famous, entrancing generations of artists and experimental musicians. Part of its allure is formal: the patterned spread of hexagonal tile on the floor creates a strong, almost diagrammatic perspective in the foreground, which then terminates in a jumble of boxes against the back wall. The effect is deeply classical, not unlike some paintings by the 15th century master of perspective Paolo Uccello. In the photograph, the two men appear dwarfed by the giant instruments. Together, they seem composed but slightly ill at ease, late-19th century men adrift in a 20th century world of inflationary geometries. The whole scene is suffused with the decline of the Belle Epoque.

Luciano Chessa, a musician and musicologist, has studied this photograph intensively for several years. He is probably the world expert on this picture and on its close cousin, an alternate exposure of the same scene with a slightly different arrangement. Ever since he began looking at the photos while writing his dissertation on Russolo (published in 2004), he hasn’t been able to leave them alone, mining them for their every minute detail as a documentary record of the instruments. When RoseLee Goldberg, impresario of the Performa festival in New York, invited him to recreate the instruments for concert performance in 2009, he began an extended project of reconstruction. At once scholarly and creative, Chessa’s project recreates a technique of the historic avant-garde, bringing it into the present in a necessarily altered form. Given its massive scope, it also raises historically complex aesthetic, political, and musicological concerns that have so far escaped serious critical review. This essay attempts to situate and evaluate Chessa’s remobilization of the intonarumori within each of these realms.

Many less ambitious reconstructions have been attempted in the past, mostly for museum displays, with varying degrees of success. Some examples were on display at the exhibition Sons et Lumieres at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2004. I remember them being shown on plinths as sculptures, off-limits to the public, and perhaps with good reason. At the 2006 Russolo retrospective at the Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto in Italy, all but three of the rebuilt instruments were broken in the first few days of the exhibition by visitors who, it must be assumed, played too hard. Oh, interactive art.

The main logistical problem attending all efforts at reconstruction of the intonarumori is the dearth of historical material. While a wildly varied written record of letters, memoirs, and concert reviews that describe the historic performances can be found, and some patent drawings have survived, the original instruments no longer exist.1When Russolo went to Paris during World War II, he deposited the instruments at a school in Milan, where they were stored in an auditorium, and apparently used occasionally as sound effects for school plays. Later, retreating German soldiers stayed in the auditorium where, according to speculation, the instruments were used for firewood.2 Only one sound recording of the instruments exists, a two-sided Gramophone disc from 1921. Unfortunately, the sound quality is dismal, and the piece is not representative of Russolo’s intentions.3

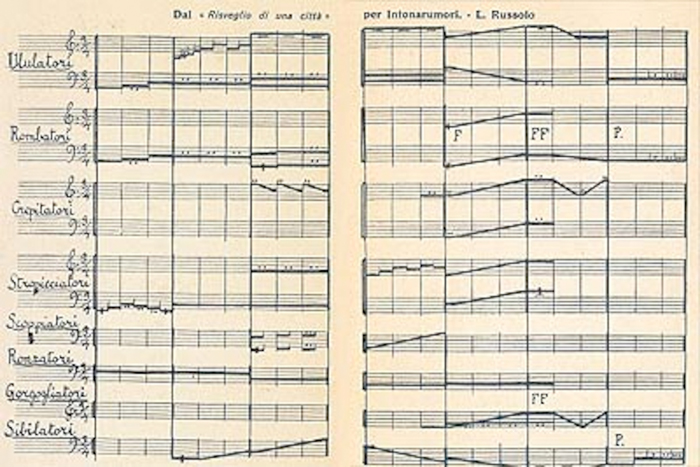

The other great lacuna is the almost total disappearance of any original scores. The only extant fragment contains the opening seven bars of Russolo’s Risveglio di una citta (Awakening of a city), which has survived only because it was reproduced in a magazine. As fragmentary as it is, Russolo’s graphic notation is both radical and influential, and employs the traditional five line musical staff only to indicate the pitch span of each individual instrument, with no consistent harmonic meaning. Glissando lines use the space as a microtonal continuum, without discretely pitched notes. In other respects, however, the score is oddly conventional, using bar lines and a 3/4 waltz time. Trained as a painter, Russolo was (as he put it) “bolder than a professional musician could be, unconcerned by my apparent incompetence.”4

Excerpt from Luigi Russolo’s score for Risveglio di una città (Awakening of a City) for intonarumori, published in Lacerba (March 1914).

Given this fragmentary evidence, any reconstruction of the intonarumori is highly speculative, dependent on the interpretive predilections of the maker. Chessa’s project thus raises material and interpretive questions that compare to and perhaps even surpass the quandaries faced by specialists in early-music performance. Chessa, who has a degree in 14th century music, about which information is often scarce, was perhaps uniquely suited to the task. Unlike previous rebuilds, which have mostly been completed by carpenters and engineers, Chessa’s instruments were made by a luthier, Keith Cary. Cary is a Californian with a background building banjos.

In all of the sonic details of their reconstruction, Chessa and Cary have chosen to err on the side of espressivo, choosing range, sonority, responsiveness, and an Italianate musicality over the merely mechanical or charmingly maladroit. The ululatore (howler) family, in which there are a few different ranges, carries some of the tone of a conventional string instrument–a scratchy violin, or a scraped stand-up bass. The crepitatore (crackler), which employs a rotating notched wheel repeatedly plucking and damping a string, can sound like a steel string guitar played with tremolo picking, although with a very strange flange-like pitch-wobbling effect. The sibilatore (whistler) is akin to a wind machine. The bass instruments, in particular, are impressively loud. The rombatore basso (bass roarer) growls like some kind of satanic hurdy-gurdy, a low rumbling screech that is deafeningly loud by pre-electronic standards, and probably even louder than the original instruments.5 Each instrument has approximately a 10-note range. They are mostly human powered (though, as in the originals, a few use electric motors) and the human element creates an unstable, organic quality that is aurally quite different from the fixed washes and precise fades of most contemporary electronic noise music. The instruments have particularly interesting and somewhat unpredictable effects when operated in their extreme registers, or when cranked at very slow or very fast speeds. Their characteristic motion is a glissando-like slide; melodic leaps are difficult to perform. While it is primarily the world of industrial machinery that is evoked, the tones of the instruments are also occasionally reminiscent of animal sounds: a lion’s roar, a cow’s moo, or the trebly ratcheting of cicadas.

II. Back to the Futurism

The logistical problems of any revival of Futurist aesthetics are accompanied inevitably by the political problems. The 1909 Manifesto by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, published on the front page of France’s leading newspaper, states his program baldly: “We want to glorify war–the world’s only hygiene-militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman. We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.”6 Yikes. Although Marinetti was one of history’s greatest hyperbolists, and apologists over the years have tended to take his declamations light-heartedly, he doesn’t really seem to have been speaking figuratively.

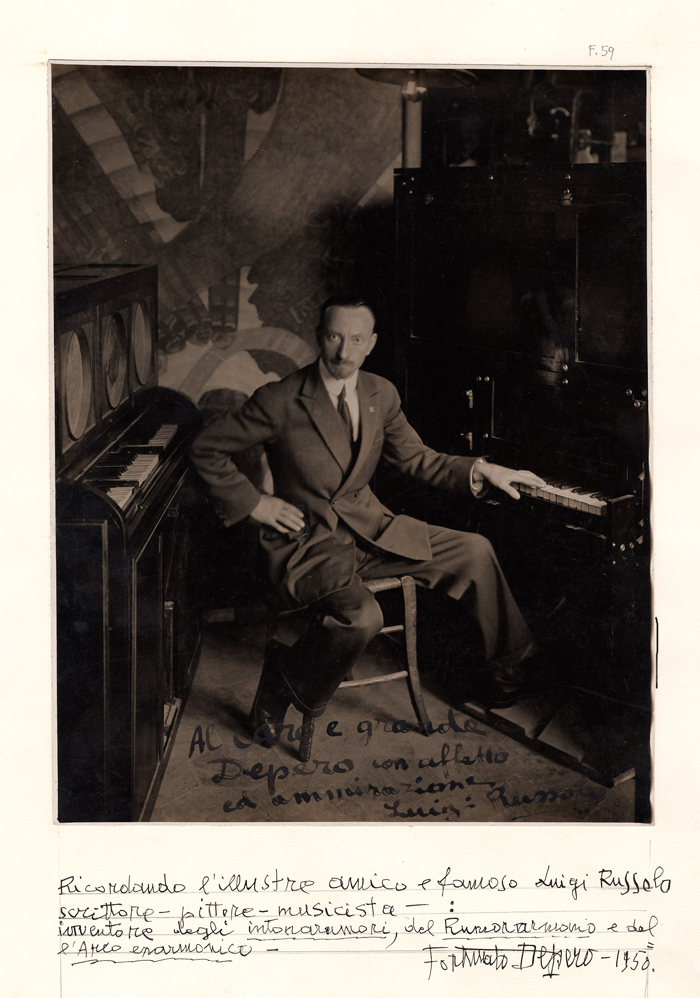

Luigi Russolo at Russolophone (with Depero’s dedication), 1934. Courtesy of Rovereto, Mart, Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero.

Russolo’s manifesto L’arte dei rumori (The Art of noises), published in 1913, channeled these sentiments into music, although no instruments had yet been built:

For many years Beethoven and Wagner shook our nerves and hearts. Now we are satiated and we find far more enjoyment in combining in thought the noises of trams, backfiring motors, carriages and bawling crowds than listening again to, for example, the “Eroica” or the “Pastoral.”7

Russolo then quotes what he calls a “marvelous” free verse poem by Marinetti describing a battle of the Italo-Turkish War:

load! fire! what a joy to hear to smell completely taratatata of the machine guns screaming… shrapnels waving arms exploding very white handkerchiefs full of gold srrrr-TUMB-TUMB raised grenades tearing out bursts of very black hair ZANG-srrrr-TUMB-ZANG-TUMB-TUUMB the orchestra of the noises of war swelling under a held note of silence in the high sky round golden balloon that observes the firing…8

Marinetti was responding directly to current events; Italy’s invasion of Libya was the first war in which bombs were dropped from airplanes. But after quoting this poem, Russolo then affirms it: “We want to attune and regulate this tremendous variety of noises harmonically and rhythmically.” In case any question remained, the category “Voices of animals and men,” one of the six “Families of noises of the Futurist orchestra,” includes only the sounds of suffering and distress: “Shouts, Screams, Shrieks, Wails, Hoots, Howls, Death rattles, Sobs.”9

Luciano Chessa conducting Joan la Barbara and the Magik*Magik Orchestra in the premiere of la Barbara’s “Striation” as part of Music for 16 Futurist Noise Intoners. A Performa commission, 2009. Photo by Paula Court, courtesy of Performa.

Marinetti’s rhetoric is fundamentally repulsive. While the daily lives of the Futurists were undoubtedly more prosaic than their manifestos might suggest, and Marinetti’s overpowering editorial control of the Futurist publications must be taken into account, the aspirations expressed in these statements are fundamentally abhorrent, and demand serious confrontation in our own era, which has not shaken a collective psychological bias towards war. From the very beginning, Futurism’s ideological overlap with fascism’s infatuation with youth and its program of speed, technology, and violence against the opposition was more than circumstantial. But the story resists simplification, and not just because of dissent within the Futurist group. Even taken on its own, Marinetti’s sensibility is extraordinarily difficult to describe in contemporary terms. He courted laughter, but he was not being ironic or satirical in the way those words are used today. He has no present-day analog. Try to imagine a breathless free verse poem celebrating the showering of Hellfire missiles from Predator drones onto villagers in Pakistan, printed on the front page of Le Monde.

Faced with these interpretive difficulties, most casual accounts of Futurism, molded by a formalist narrative anchored by the Museum of Modern Art, have in general been unusually forgiving with regard to its politics, telling a simplified story that positions the movement simply as another school of painting to grow out of Cubism. This narrative has become unglued in the visual arts, and is now under attack from all sides. It is perhaps only in music that we still can entertain a pure formalism that separates an object permanently and utterly from its era, and even from its creator’s stated intentions. It might be argued that a composer’s intentions are irrelevant, and that the work stands utterly apart from its originary context. While not wrong, the emergence of this viewpoint is itself, however, broadly circumscribed by historical contexts, and a host of governing prejudices that collectively determine what a work is, which phenomena are considered works, and where the boundaries of these works lie. The content of music, the most abstract of all the arts, is notoriously difficult to specify. Its political content can easily appear to accrue entirely from its context, and the musicologist’s task of restoring an original context for a work can easily compete with or even contradict the musician’s goals of expression, with its traditional emphasis on originality. Yet, as in the better-known cases of Wagner and Heidegger, the taint of fascism must be acknowledged, grappled with, and not oversimplified by an artificially strict separation between disciplines.

III. The San Francisco Concert

In 2009, Chessa’s reconstruction project culminated in two concert programs of mostly new music composed for the reborn intonarumori, one in San Francisco at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and one at Town Hall in New York as part of the Performa festival. I saw the San Francisco concert, which was a wild ride through the playbook of “new music” composition.

One texture that recurred throughout the evening was that of an “all-in” orchestral density, with each player at full volume, creating the swarm-of-bees sound-image so beloved of the 1950s avant-garde. This was the basic mode of both Elliot Sharp’s Then Go, and Mike Patton’s <<KOSTNICE>>, both of which supplemented the intoners with percussion. These pieces were essentially confrontational; they acted as musical scare tactics, sound-images of bombardment, disorientation, and panic. Pablo Ortiz contributed Tango Futurista, a sophisticated and humorous piece that set the sounds of the intoners to folk rhythms, perhaps an ironic nod to the waltz time of Russolo’s Risveglio. Anomalous in the program was James Fei’s New Acoustical Pleasures (A Furious Meow), which was composed of quiet, brief sounds, separated by silences. Cage-ean in its static simplicity, it sounded at one point like someone alone in a room moving a heavy piece of furniture, nudge by nudge.

The concert opened with Paolo Buzzi’s Pioggia nel pineto antidannunzaniana (Rain in the anti-D’Annunzian pine forest), a theatrical show-starter with fragments of language, in Italian, shouted through a megaphone over the grunting of the instruments. The score was “realized” from a sort of graphic score that Chessa found in the right margin of the manuscript of Buzzi’s 1916 poem, a satire of idyllic forest sounds disrupted by urban noise.

Perhaps the most successful piece of the evening was a group improvisation near the beginning of the program, titled let us return to the old masters… The title is a cheeky reference to the 1910 Manifesto of Futurist Musicians by Francesco Balilla Pratella, which states the goal of “declaring the phrase ‘let us return to the old masters’ to be hateful, stupid, and vile.” The improvisation was developed out of experiments that took place during the rehearsal process, and exploited a hands-on familiarity with the idiosyncrasies of the instruments that the composers, working at a geographical distance, were perhaps not able to call upon. (Many of the composers worked out of necessity from short demonstration videos of the instruments that Chessa created and posted on a website.)

One of the paradoxes of this music is that while its scores consist visually of lines, the sonic results are typically not musical lines but blocks. These slabs of sound tend to exist more or less independently in musical space, in a landscape of sound events whose structure can seem overly indebted to visual metaphors, and often lacks any music-specific principle of continuity. The general absence of harmonic tension is compounded by the similarity of the noise-sounds, which causes them to aggregate almost too readily when sounded simultaneously, tending to defeat the possibility of polyphony. This aggregation was in fact Russolo’s stated goal, but it is an extremely steep price to pay for the expanded timbres on offer. In addition, the shifting glissando-like effects that the instruments easily produce, while fascinating on the first and even the fourth and fifth hearing, can grow familiar and even tedious over the course of two hours.

Chessa’s own piece, L’acoustic ivresse (The acoustic breeze), was one of the few pieces to manage these problems, sustaining polyphony through careful orchestration. It added the bass vocalist Richard Mix to the ensemble, who sang the text to Paolo Buzzi’s poem “Russolo,”10 a Baudelairean ode to the instrument-builder steeped in mysticism and death. The poem was sung in the original French, but listeners could follow the English translation in the program notes. Mix’s vocal technique alternately blended and broke with the noise textures, mixing layers of noise glissandi with a kind of mutant bel canto. Chessa’s score and musical approach demanded relatively specific pitches from the instruments, aided by marks near the levers on the instruments corresponding roughly to various approximate pitches within each instrument’s range. It was thus a powerful study in the utter derangement of harmony, one that interrogated the limitations of the instruments themselves as a kind of musical material, acknowledging and occupying the gap between their sound production and the perfectly intoned harmonies of classical music. Its perverse treatment of harmony was the most ambitious of the evening, and the piece was met with the warmest applause by the packed house.

IV. The Musician and the Musicologist

For Chessa, Buzzi’s poem “Russolo” does double duty both as a musical resource and a musicological source. Drawing on the specific language of this and other texts, Chessa’s UC Davis PhD thesis radically positions the intonarumori as literally being instruments of the occult. His survey of Futurist practice broadly recreates the intellectual and popular milieu in Milan around 1913, showing it to be steeped in the vocabulary of spiritualism. Rejecting the view of Russolo as simply a materialist scientist, Chessa points to the immersion of the Futurists in the vocabularies of Theosophy, thoughtforms, telepathy, parapsychology, clairvoyance, and perhaps even necromancy. These contexts lend a literal meaning to the words of Buzzi’s poem:

Luigi, the ululatore is the oracle

Of God who inspires you and who will render you

justice.

The abyss, our illustrious Relative, is grateful to you.

I hear only the true music: those

That the dead hear.

Over their heads, under our feet.

The future City awakens

In an explosion that invites

The cemeteries to masked balls of power and desire!

It would be tempting to read the language of the poem figuratively, except that, as Chessa shows, Russolo apparently genuinely believed that he could communicate with the dead.11

Later in life, Russolo laid out his interests in spiritualism explicitly. His philosophical book Al di la della materia (Beyond matter), first published in 1938, describes a “doubling of the body,” attached by a kind of umbilical cord to its subject, which is able to roam the room independent of its source, even moving objects around.12 Chessa’s research, however, pieces together an argument for a much earlier manifestation of these interests, during the period of the intonarumori. Chessa is careful not to speculate too much, and there is no single precise textual “smoking gun.” But it seems highly possible that Russolo, in his own mind, was attempting through his touring concert program nothing less than some kind of conjuring of spirits on a massive scale. Given the taboos against black magic, it would only be logical for Russolo to have surrounded this project with secrecy and even perhaps obfuscation, which would explain the lack of direct evidence for his approach.

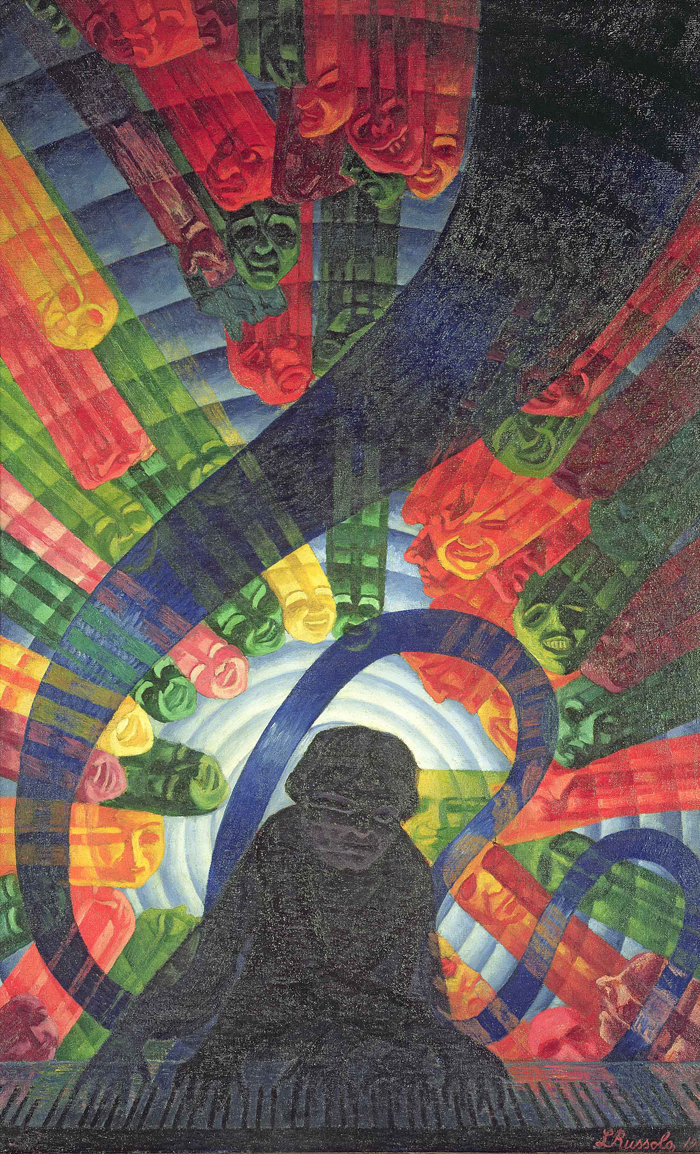

Luigi Russolo, La Musica, 1911. Oil on canvas, 88 1/2 x 55 in. Estorick collection, London.

The favorite meeting ground for spiritualism and technology in the period was the theory of vibrations: the idea that X-rays, light waves, and sound waves were all manifestations of the same basic etheric phenomenon, differentiated only by frequency, wavelength, and intensity. Vibrations in one form could thus excite vibrations in another form. It was in the field of painting that Russolo first registered interest in this notion. The massive oil on canvas La Musica (1912) shows a shadowy keyboardist/medium summoning masked faces that swirl through the air, called forth by a melody symbolized by a blue band. Chessa argues convincingly for the Theosophical character of the painting, with its synesthetic rendering of sound waves as vibrating visual “waves.”13 X-ray images also fueled speculations of a universe of vibrations outside the ordinary perceptible world. Magnets and X-rays were thus of particular interest to spiritualists, including Russolo, who seems to have built some kind of X-ray device in his studio.14 Experiments in magnetism, spirit photography, and “ideoplastic materialization” seem to have followed. Russolo, under the influence of Theosophy, appears to have sought a kind of metaphysical rationalism, in which spiritualism and technology were not opposed but united. From Russolo’s point of view, abstraction alone was not sufficient: “Music must move away from an abstract indefinite, which is the characteristic of its language, of the matter which it uses, to arrive at a spiritual infinite.”15

Chessa’s research both follows and extends a wave of recent research into the historic avant-garde’s relationship to the occult. A critical turning point in this discussion was the publication of Okkultismus und Avantgarde: Von Munch bis Mondrian, 1900-1915, the catalog to a show in Frankfurt in 1995. This massive anthology of critical essays presented an extended double take on the staid formalist orthodoxies of popular art histories of the European avant-garde. However, there is still relatively little on the subject in English. Broadly, the new research, while turning up some interesting new facts, anecdotes, and objects, relies mostly on the strength of close reading, essentially just taking the avant-garde at its word. It treats seriously the sometimes confused, difficult, and purposefully vague spiritualist language of the period, language that formalist interpreters have ignored for almost a century as poetic, rhetorical, or simply embarrassingly regressive. Basically, what’s emerged from this return to primary sources is that the Futurists in particular were a whole lot nuttier than the MoMA narrative lets on. The crowning absurdity comes in 1933, in Marinetti’s introduction to Il Macchinismo, a late manifesto that proposes a technique for reanimating the dead: “The idea of mechanization of the dead obtained by metallizing their essence may seem insane but when seriously studied and pondered, it can offer unforeseeable ideological and practical solutions!”16

It is common for those who deeply study a historical personality for a long time to become enmeshed in the character of their subject. The ego shifts analysis imperceptibly towards the mimetic and the affirmative; after a few hundred pages the quotation marks start to slip away. For example, we find Hubert Dreyfus’s 25-years-and-running interpretation of Heidegger invisibly blending into its object of study, supplying a lucidity but also a tolerance that the original plainly does not have. The result: “Dreydegger,” a fascinating but ahistorical Frankenstein, a Nazi with liberal multicultural sympathies. Chessa’s decade-long scholarly immersion in the world of Russolo courts a similar merging. His thesis is no hagiography, but his empathy for Russolo is palpable, and there are moments when the interpreter and the interpreted bleed into one another. We thus catch a glimpse of “Chessolo,” a historian/musician composite who seamlessly bridges the spiritualism of the historic avant-garde with a friendlier, neo-liberal, yoga-mat spirituality of the present day. This composite figure is sympathetic, but also critically suspect. It is perhaps impossible for a creative personality to study the past without assigning it a contemporary language. But an archeology of noise music (like any archeology) carries with it the risks of distorting its subjects in the course of cleaning them up for display. To his credit as an academic, Chessa catches himself doing it, and he restores order by opening his final concluding section with the disclaimer: “Whether or not I believe in black or red magic, in mediumistic seances or in ideoplastic materializations, matters little. What I have felt it important to emphasize is that Russolo and other Futurists believed in these things from the very beginnings of Futurism.” From the musicological point of view this is perfectly clear; but the problem is that in the concert hall we absolutely do want to know if Chessa the composer believes in “mediumistic seances”! We want to know Chessa’s intentions for the same reasons that we want to know Russolo’s intentions. Chessa recalls that when he described Russolo’s spiritualism to some of the commissioned composers, they nodded affirmatively. But one has to wonder what was being affirmed exactly, because the spiritualism of the historic avant-garde is not contemporary spirituality.

Fascism remains the wolf outside the door in this discussion. Even at a distance, it complicates any effort to recuperate Russolo’s early work, because the same formalism that has allowed some musicians to claim Russolo as something like the Father of Noise Music is also the barricade that has kept the ugly politics of 1913 from contemporary consciousness. Chessa thus performs a difficult balancing act, returning the repressed spiritualism of Russolo to public view in his scholarship, and at the same time laying some claim to the lineage of Futurist thought in his own musical projects, while sidestepping the political question. A short text fragment in Chessa’s program notes for the San Francisco concert urges: “After the noises of War, let’s embrace the noises of Peace.” It’s a nice aspiration, but also puzzling, considering that the concert it accompanies was in many ways what Russolo’s original manifesto originally called for: an aestheticized form of panic, this time framed through the sanitizing mirror of nostalgia.

V. Sound and Superstition

It is impossible to neatly summarize the century that separates us from the first intonarumori concert, or the historical changes that underlie the shifts in their signification. But to get there from here one must at least touch down at the temporal midpoint, at the divided response to noise music in the postwar period. The decisive figure remains Theodor Adorno, and the decisive text is his magisterial essay The Aging of the New Music (1955), in which he discusses how, in the aftermath of Expressionism (both musical and painterly), sound itself came to be confused with expression. It is worth quoting at length:

The totally new, many layered sounds of the New Music were conceived of as bearers of expression. And this they were, but in a mediated way, not immediately. Their individual values depended partly on their relation to traditional sounds that they negated and through this negation preserved in memory, and partly on the position of the sounds in the structure of the compositions as a whole, which they at the same time contributed to changing. On account of their newness, however, the expressive qualities were at first attributed to isolated phenomena of the sounds themselves. This was the origin of a superstitious belief in intrinsically meaningful primitive elements, which in truth owe their existence to history, and whose meaning is itself historical. Even radically minded artists barely withstood such superstition…. To be sure, the material does speak but only in those constellations in which the artwork positions it; it was this capacity to organize the material and not the mere discovery of individual sounds that from the start constituted Schoenberg’s greatness. The inflated idea of the material, however, which clings tenaciously to life, misleads a composer into sacrificing the ability, insofar as he has it, to form constellations and encourages him to believe that the preparation of primitive musical materials is equivalent to music itself.17

Adorno was writing about the serialist composers, not Russolo, whom he ignored with majestic disdain. But there is no more ready target for any charge of a “superstitious belief in intrinsically meaningful primitive elements” in all of the 20th century than Russolo. The “bruitistic” (to use Adorno’s word) mysticism that Russolo embodied was, as far as Adorno was concerned, mediocrity incarnate. Adorno’s argument, bounded as it is by both an almost exclusive concern for the tradition of European art music, and a monstrous arrogance and hostility towards every form of popular culture, nevertheless articulates the theoretical basis of a powerful skepticism towards the musical value of new sounds per se. There remains today, just as fifty or one hundred years ago, a risk of falling into the critical fallacy that more is always better, into the assumption that an increase in formal materials and instruments will automatically lead to an increase in expressivity, when there exist powerful historical arguments to the contrary.

Luigi Russolo, Self Portrait, 1909. Oil on canvas. Civico Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy. Photo: Photoservice Electa Mondadori / Art Resource, NY. © Luigi Russolo.

Adorno and the Frankfurt School in general may be said to have dismissed Futurist thought, but it was out of ideology, not out of ignorance. If, as Adorno argued, musical meaning essentially comes from structure, then musical sounds must be both flexible enough and consistent enough to interact meaningfully within a wide range of structural “constellations,” and not just as ornamental effects. This would seem to have the practical effect of ruling out simplistic noise instruments as serious tools of composition. If a musician’s determination to simply “let sounds be sounds” results in a collapse of structure, that in turn could result in a vacuum of subjective meaning. The argument and enormous influence of The Aging of the New Music mark the end of a phase of Modernism, and by the late fifties serious music in Europe would be characterized by a mixture of approaches that continue to this day under the banner of Postmodernism.18

On the other end of the spectrum during this same period, the most rousing celebration of noise would come, of course, from John Cage. Though he couldn’t have heard the intonarumori, Cage was familiar with Russolo’s manifesto, obliquely acknowledged his influence, and even appears to have paraphrased him somewhat in certain passages of his early writings.19 Both composers pursued abstraction, but where Russolo insisted on aggregating sounds to force them out of the realm of the purely imitative, Cage in his middle period insisted on the separation and individuation of sounds, the better to contemplate in isolation. Cage’s writing (which his music basically illustrated) fundamentally and radically questioned the Beethoven-centric ideology that privileges musical structure over sound. Cage accepted the distinction between what he called “powers of audition” (the instincts and skills involved in recognizing new sounds) and what he called “powers of relation” (intellectual abilities that relate to the skills of Adorno’s “structural listening.”) However, he simply concluded that powers of audition were historically undervalued, and that (to oversimplify only a little) harmony as traditionally understood could be dispensed with for an art that was essentially about musical duration and its own immediate circumstantial environment. Cage introduced noise into existing musical structures, and pointed at subtle forms of noise that were already present in musical conventions, environments, and technologies, most famously through the use of chance operations.

The conflict between these two fascinating, polarized, and deeply flawed approaches of Adorno and Cage continue to structure the experience and interpretation of new music to this day. Adorno, for his part, acknowledged Cage’s early work (the Piano Concerto) but with a telling reservation, and one particular passage on Cage from Adorno’s late essay “Difficulties” cuts to the core of the Russolo/Chessa question:

[I]n their effect the extremes of absolute determination and absolute chance coincide. Statistical generality becomes the law of composition, a law that is alien to the ego. Certainly the absolute indeterminacy of Cage and his school is not exhausted in it. It has a polemical meaning; it comes close to the dadaist and surrealist actions of the past. But their “happenings,” in keeping with the political situation, no longer have any politically demolishing content and hence tend to take on a sectarian, seance-like quality-while everyone believes that they have participated in something uncanny, nothing at all happens, no ghost appears.20

A more precise description of the problems involved in an authentic centenary performance of the intonarumori could hardly be imagined. For if what Adorno wrote in 1964 was not exactly true of Cage’s now-legendary performances, the developments in culture since then have removed any element of hyperbole. The flesh has fallen from the bone, and the leftover armatures of avant-garde spiritualism in both painting and music often seem merely quaint today, with their true historical content mentally inaccessible. The willing audience’s feigned suspension of disbelief has in turn become its own kind of shallow ritual.

Antonio Russolo’s orchestra in Paris, 1921. Antonio Russolo is on the far left. The orchestra also played intonarumori by Luigi Russolo. Courtesy Rovereto, Mart, Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Russolo.

The risk of a refashioned intonarumori performance is thus not that of a pseudo-seance in which the crowd loudly jeers in disbelief, which after all is what happened at many of the original 1914 performances.21 It would be hard to elicit or even imagine such a riotous audience response today, given the proprieties of contemporary new music culture. Rather the danger is that of a pseudo-seance that simply digs the audience deeper into the cliched postures of irrationalism in art. The greatest danger, in fact, would be the risk of some chance phenomenon, of something vaguely supernatural actually seeming to appear, against the expectations of all, probably including Chessa himself! Spiritualism is not the only cultural antidote to an excess of paranoid logic. If Cage’s performances, as Adorno suggested, inherited the spiritualism of the historic avant-garde in a reduced vestigial form in which “no ghost appears,” then today we stand at a double-remove. The historical climate that underwrote Theosophy, parapsychology, and “ideoplastic materialization” is no longer a living memory. Remembrance cannot restore it and should perhaps not even attempt to.

Meanwhile, the form of musical irrationalism that Russolo pursued in his Futurist period has long since been popularized in entertainment. It finds its utmost popular expression in the figure of Mickey Mouse as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice in the Disney film Fantasia (1940), an image of the symphony conductor as conjuror. In the film, the apprentice falls asleep after casting a spell on a broomstick, and his etheric double rises up into the air to conduct a symphony of spiraling lights. The parallel with Russolo’s experiments, writings, and paintings is striking. The animated images of this sequence in Fantasia are in fact, however improbably, the not-so-distant progeny of Russolo’s La Musica. In the Disney film, however the occult irrationalism that the Futurists brought into the mainstream of Modern Art has been sterilized. The spiraling masks of the painting have been abstracted into animated balls of light, and the spiritually vibrating waves of sound have been literalized as crashing ocean waves. The narrative of the segment underscores the accommodation to the American middlebrow. When the sorcerer reappears at the end of the sequence to scold Mickey for his negligence, order is restored, paternal authority is affirmed, and no damage has been done. The etheric double that Russolo sought to establish in reality later becomes, in Fantasia, only an entertaining metaphor.

Luigi Russolo, The Revolt, 1911. Oil on canvas, 59 x 90 1/2 in. Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands / the Bridgeman Art Library.

But it is not that “we are all Futurists now.” Quite the opposite, today everything must find some pre-built historical rack to hang on, which is Futurism’s very antithesis. The chief symptom of this historicist sequelmania is that any “political” valence is today identified and experienced as an insertion, as a figure on the monochrome ground of consensus reality, and not as part of the fabric of social exchange itself. Instead of art as a by-product of history, and as a necessary and embodied deposit of a form’s historically accrued relationship with its audience, we have a universe of pre-regulated meanings, programmatically fixed through scholarly administrative fiat, and a present that is being ventriloquized continually through the past. This strange hollowing out of the present is itself a political development. The risks and rewards of music lie as always in the dynamic between the audience and the work, at this moment caught in the scholastic temptations of an ascendant cult of history, and in the troubled and troubling “museumification” of sound, both of which cut against the only aspects of Futurism worth preserving for the constantly disappearing present.

Benjamin Lord is an artist based in Los Angeles. The writer would like to thank Luciano Chessa for providing some access to the instruments, for access to his research, and for fielding questions regarding Russolo and the Futurists. Chessa’s book Luigi Russolo Futurista: Noise, Visual Arts and the Occult, the first monograph on Russolo’s Art of noises, will be published in 2011 by University of California Press.