Lee, In Production (3), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Lee, In Production (3), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Lee, In Production (3), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Lee, In Production (3), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Lee, In Production (3), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Lee, In Production (3), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

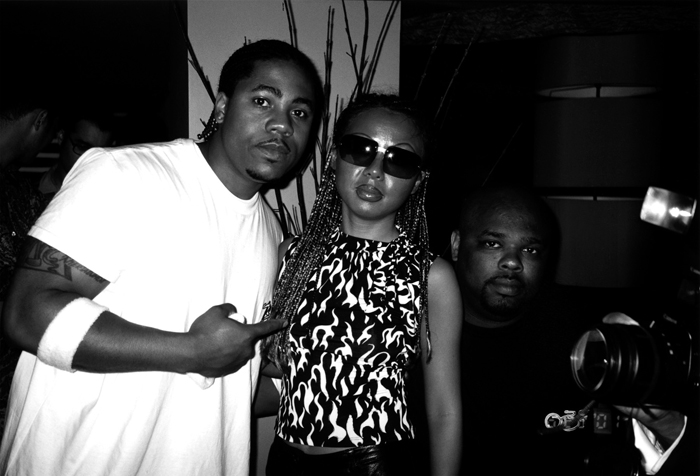

Nikki S. Lee is best known for several series of photographs, entitled Projects (1997–2001), in which she appears as a member of various American subcultures. The snapshots, taken by friends, document her temporary immersions into the roles of Japanese East Village punk in The Punk Project (1997), tough barrio chick in The Hispanic Project (1998), Wall Street professional for The Yuppie Project (1998), old woman for The Seniors Projects (1999), hip-hop girl in The Hip Hop Project (2001), and stripper in The Exotic Dancers Project (2000), among others. In transformations that can last months, Lee alters her body by pumping it up, changing her weight, and modifying her hair and make-up. She took dance lessons for The Swingers Project (1998-99) and learned radical skateboard moves for The Skateboarders Projects (2000). She exhibits the resulting photographs with the various series mixed together so that the only constant is Lee’s chameleon-like presence—an oddly familiar but constantly changing Asian face that seems to be everywhere at once.

Lee arrived in New York from her native Korea in 1994 to study fashion, received an MA in photography in 1999, and later merged her two interests by working in fashion photography. Her self-transformations began early, when she changed her name from Lee Seung Hee upon arriving in the U.S. As perhaps only an outsider from a far more homogenous society could, she began noticing the different melting pot-resistant groups that make up contemporary, mostly urban, American culture, honing in on the details of group identity. When Lee embarks on one of these Projects, she identifies herself to her new friends as an artist and explains that she is working on an art piece. With a winningly guileless personality and a genuine lack of condescension toward her subjects, she is welcomed into the gang and remains for a few weeks to several months. Lee’s immersions are often so complete that participants—such as the old ladies she befriended and the audience she expertly regaled in the stripper club—were convinced she was the real thing. Rather than attempting a critique of group identity, Lee’s projects imply that she relishes her immersion in these subcultures. In Lee’s series Parts (2002-2004), she posed with different men, but cropped them out of the pictures so that only a hand or a sliver of a shirt, as well as her casually intimate poses, characterized the men as lovers. In each of these images, Lee looks different, as if changing according to the persona of her barely-represented, temporary boyfriend.

Nikki S. Lee, In Production (9), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Nikki S. Lee, In Production (9), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Nikki S. Lee, In Production (9), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Nikki S. Lee, In Production (9), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Nikki S. Lee, In Production (9), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Nikki S. Lee, In Production (9), 2006. Color Fujitrans in light box; 10-1/2 x 43-7/8 inches. Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Much has been made of Lee’s debt to Cindy Sherman. In their most iconic works, both artists depict themselves in various guises, never actually revealing themselves. But while Sherman’s earlier series reflect and confront mainstream media images of women, most famously in the Untitled Film Stills (1977-80), Lee’s images explore the nature of identity within specific ethnic, racial, and class groups in contemporary America. While Sherman, like Lee, arranged her own scenarios in the Film Stills, those works engage with a narcissistic gaze (with Sherman as a lone figure in the image that she has set-up for herself) and an implied voyeuristic gaze (through the viewer being positioned with the camera). In contrast, Lee’s snapshot-style pictures mirror the local, cliquish reality of the neighborhood.

Somewhat fittingly, considering the role that acting plays in her work, Lee produced a.k.a. Nikki S. Lee, her first film in 2007. The hour-long work, which screened at the Hammer Museum in January, is a mock-documentary about the life of “the artist Nikki S. Lee” that, like her photographs, mimics documentary tropes and seamlessly confuses fact with fiction. a.k.a. Nikki S. Lee takes on the tradition of the “PBS” type artist biopic, a media form that contributes to the myth-making apparatus surrounding the figure of the artist in society. Here Lee utilizes the stylistic constructs of such documentaries expertly. At the same time, a.k.a. Nikki S. Lee reveals art world rituals in all their pretentiousness.

a.k.a. Nikki S. Lee opens with a text stating that the director of the film, who remains unseen and unheard throughout the movie, began filming Lee for a documentary about Nikki S. Lee. The introductory shot is of Lee in her studio, that most authentic site of artistic creativity, familiar from countless filmed artist profiles, being interviewed by this director, who is gradually revealed to be fictitious. Lee begins by saying that people often wonder what she is really like, and they have mistaken preconceptions of her as a party girl. The obligatory montage of her photographs accompanies her words. As if to counter this frivolous view, Lee is dressed in a workmanlike shirt against a spare backdrop of bookshelves and little else. The “studio” is actually a stage-set assembled by Lee for the film, undermining the “behind-the-curtain” quality of the studio visit.1 Intermittently the film revisits Lee in the studio in a supposed “reality-check” within the whirlwind of her hectic life. She appears speaking to the off-camera “documentarian” in an appropriately serious tone or being interviewed by various experts such as her dealer, Leslie Tonkonow, or the performance art scholar RoseLee Goldberg. Each depicted encounter parodies the impulses of art world institutions—to position the artist as a “conceptual artist” (read “rigorously intellectual”) or in another context, to very literally illustrate a discussion of the ethnic roots of her practice with a vision of the younger Lee singing traditional Korean songs.

This set up is reminiscent of another mockumentary—Woody Allen’s 1983 film Zelig. As what could be considered a precursor to Lee’s impersonations, Zelig is a “human chameleon” who adopts the mental and physical characteristics of those next to him. In color film collaged with black and white “archival” footage that fuses fact with fiction to hilarious effect, Zelig appears uncannily as a black jazz musician, Chinese immigrant, obese man, and an Aryan Nazi, tracing the popular and historical events of the decade. Zelig’s affliction is a result of his extreme desire to assimilate, and the film is a comment upon, among other themes, the dangers of conformity. While Allen’s film has an absurd and ultimately touching ending, with Zelig finding his true self through the love of his psychiatrist (Mia Farrow), Lee’s film has no such resolution or revelation of character.

Nikki S. Lee, The Seniors Project (15), 1999. Digital Fujiflex c-print. 21-1/4 x 28-1/4 inches, Edition 5; 30 x 40 inches, Edition 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Lee’s film shifts from the acetic locale of the studio to that most glamorous of art world venues—Venice at the time of the Biennale. A vision of casual chic dressed in white on a boat on the way to La Serenissima, Lee states her intentions, “For this documentary, I create Nikki Lee based on what people think her character is.” As in the Projects, Lee is forthright about her motives, letting the participants in on the ruse from the beginning. She then shows “Nikki” (her moniker for the star of the mock-documentary we are watching) partaking of the delights of the city—shopping for designer clothes and hobnobbing with collectors and celebrities. “Nikki” stays with collector friends in a grand apartment filled with art, chats up Jeremy Irons (who agrees to let her use his footage in her film) and lunches with Hollywood producers.

Various art collectors appear in different scenes in the film, some with whom “Nikki” obviously feels familiar and comfortable, such as her Venetian hosts, and others whom she meets at openings and cocktail parties. Not much is revealed about any of them. Most of them appear ill at ease before the camera, with one exception—the boisterous Long Island family. In one scene, where she is conducting research for Parts (in which she appears as a bride), Nikki visits the art-packed home of this family with three married daughters and a collection of elaborate wedding dresses. What might have been the most uncomfortable of encounters with over-the-top flamboyance is actually a peek at authenticity. The most unselfconscious of all the collectors depicted in the film, the family comes across as genuine and warm and honestly touched by Nikki’s visit. As is her talent, Nikki becomes part of the group, trying on gowns and tiaras and kissing babies. By contrast, the most awkward encounter occurs at a party at the home of the fashionable collector Yvonne Force Villareal, where a woman approaches Nikki, showers her with compliments, ending with “I love what you do,” and then abruptly walks away, leaving Nikki alone perched on a couch.

From the enforced social situations of the art world, the film turns to the “workaday life” of a successful artist. Nikki is in Frankfurt for her first exhibition in a German gallery, which generates the film’s requisite crisis point. When she arrives to install the show, only to discover the borders of her photographs trimmed off, Nikki behaves like the archetypal “difficult artist” declaring, “This is not my work” to the horrified dealer (who promises to rectify the problem). Moping in her hotel room, Nikki discusses a conversation she had with the unseen director of the film. He has asked her “to do what she normally does when she is alone on one of these working trips.” Complaining about being filmed constantly (by what is in fact her own camera), Nikki explains that she cannot perform a fantasy of her own life for the director and his all-seeing camera. As though she is speaking about her working process, Nikki recounts the director’s contention that editing is just as much about creating a fantasy as anything else. Once again, Lee is reminding us of the artifice in her work.

Nikki S. Lee, The Hispanic Project (2), 1998. Digital Fujiflex c-print. 21-1/4 x 28-1/4 inches, Edition of 5; 30 x 40 inches, Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

Several sequences of the film provide revealing views of Lee’s working method. In one scenario, Nikki works on a “Sugar Daddy”-themed photo shoot for The New York Times Magazine. First, she visits Paris to choose dresses for the shoot where she is presented as the ornately dressed mistress to a supplicant older man in various fancy settings. She is entirely in control of shoot, directing her “sugar daddy” and the photographer while dressed in couture dresses and jewels. In another sequence, the setting, a Korean/Jewish nuptial that takes place in a gilt-lined hotel lounge, is the backdrop for one of the wedding pictures from Parts. Again, Nikki is simultaneously actor and director, posing herself and others for the camera, choreographing the dancing and toasting, and always aware of her changing persona. In a third shot, taking place in a museum, she preens in a mirror that is actually part of an art installation, declaring: “Nikki is looking at herself and checking herself. That is her personality.” The ref1erence to Narcissus and the narcissistic nature of her (or any artist’s) work could not be clearer.

The penultimate scene is the most poetic and takes place in, of all places, an art fair. To the mellifluous music of Phillip Glass, the camera tracks Nikki from behind as she walks determinedly through the endless procession of gallery booths at the Armory Show in New York. In a deadpan punch line, her drawn out passage through the immense trade show concludes with Nikki simply stopping to deliver an envelope to her dealer. The climax over, she turns around and walks back again through the continuous corridors and out the door.

Nikki S. Lee, The Hip Hop Project (15), 2001. Digital Fujiflex c-print; 21-1/4 x 28-1/4 inches, Edition of 5; 30 x 40 inches, Edition of 3. Copyright Nikki S. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NY.

The final scene of a.k.a. Nikki S. Lee finds Nikki in the “studio” as she performs four takes of the same scene. She repeats in four different ways what could be the truest statement in the entire film, “I really like New York because New York is the only place I can be Nikki.” Her repeated attempts to “get it right” alert us to the contrivances in the film and raise questions about the credibility of everything we have seen. The phrase, however, also reflects the truth of Lee’s experiences in New York. Arriving from a far more conventional and homogenous society, the newly immigrated and re-named Lee embraced the opportunity to adopt, however temporarily, the attributes of various ethnic and cultural tribes in her new home. Watching her go through so many transformations, we might expect the “real” Lee to emerge, but here again she plays with our expectations and desires to “know” the real artist. The interviews, opening parties, and lectures are all a vain attempt to reveal the true nature of any artist. In this era of the inflated contemporary art market and the “branding” of people as products, Lee knows that “Nikki” is the ultimate commodity. Yet, as in her group immersions, Lee is implicit in the machinations of the art world, gamely partaking of the games. The film, like her photographic project, is neither overtly cynical nor naive. It is simply a reflection of a particular social and commercial system, in this case one which benefits the artist. The moral ambivalence that emerges is perhaps the most honest response any of us who are part of the art world can attempt.

Amada Cruz is the Program Director of United States Artists, a new non-profit organization based in Los Angeles that provides grants to artists working in various disciplines.

Jeffrey Sturges, Nikki S. Lee, 2006.