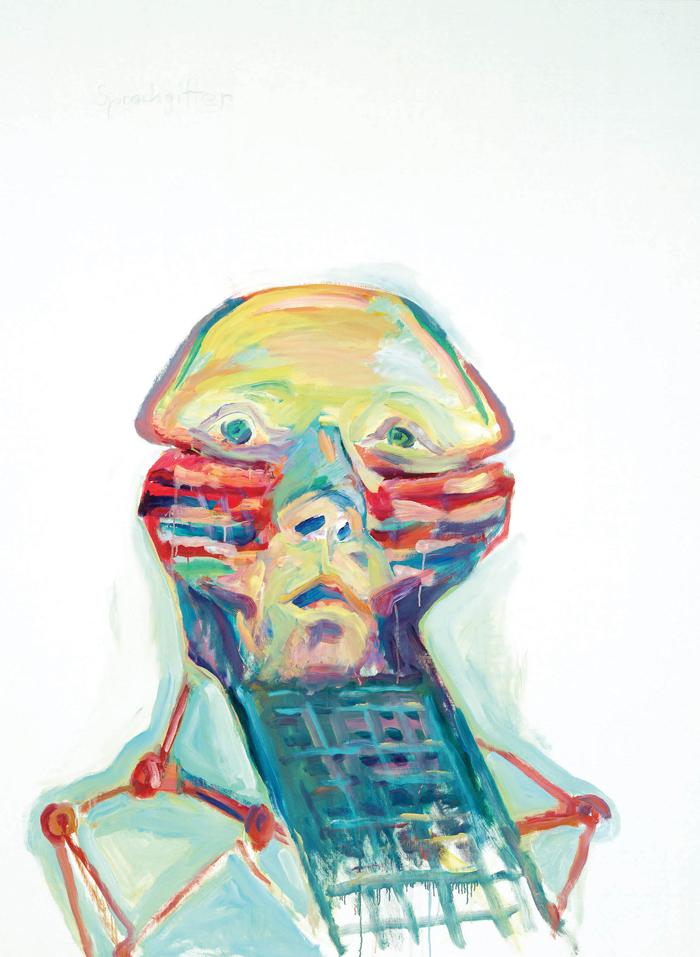

Maria Lassnig, Sprachgitter/ Language Grid, 1999. Oil on canvas, 80 3/4 x 59 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth Collection, Switzerland. © Maria Lassnig.

Maria Lassnig (born in 1919 in Carinthia, Austria) trained at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna. In the 1950s and 1960s she was exposed to Surrealism and Art Informel in Paris, and she counted the Viennese Actionist Arnulf Rainer as a friend. From 1968 to 1980 she resided in new York, where she did pioneering work in animated film. At the urging of fellow artists, she returned to Vienna’s University of Applied Arts in 1980 to become the first female professor of painting in the German-speaking world. She represented Austria at the 1980 Venice Biennale, and she participated in the pivotal documenta 7 of 1982 and in documenta 10 of 1997. In commemoration of her ninetieth birthday, exhibitions were held at the Museum of Modern Art in Vienna, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, and at London’s Serpentine Gallery. Described as the sleeper hit of the season, the London show introduced her work to an English-speaking public.

In an elegant essay for the Vienna and London exhibitions, Jennifer Higgie characterizes Lassnig’s art as a struggle between two worlds: “the surface (of the skin, of the painting, of paint), and the inner world (of the painter, of the person looking at the painting). The artist is at once herself, the body she inhabits, and the subject of her own creativity.”1 Lassnig’s art certainly conveys a struggle between inside and outside, between the artist as subject and the artist as object. And it is concerned with expression—with bringing the inside to the outside, with bridging inside and outside. But Lassnig’s works of art also negotiate the separation between sensation and awareness inside the self, that fissure between feeling and articulation papered over by consciousness.

Lassnig has coined the terms Körpergefühl (body sensation) and Körperbewusstsein (body awareness) to describe her art. The use of these two terms reveals the rub: to sense and to be aware of sensation are two separate things nonetheless bound together. Her art is either body sensation or body awareness, and it is both at once. That said, hers is anything but a postmodernist free-for-all of the self. Rather, her best work hovers existentially on a razor’s edge between sensation and awareness, as it explores the sensate self and expands the frontiers of the self-portrait.

In his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences of 1817, G.W.F. Hegel evoked the separation between sensation and awareness, or feeling and articulation, as a divide between voluntary and involuntary memory.2 Voluntary memory refers to exterior or conscious memory, to productive memory that can be voluntarily recalled. Involuntary memory implies a deeper, interiorizing memory that lies forgotten and must be called to mind. Calling the material of the involuntary memory to mind alters its original form, however. Involuntary memory remains immaterial, fleeting, or at best distorted.3 Hegel likens the involuntary memory to the mine and the well, to shafts whose depths can be penetrated but whose contents can never be perceived in their fullness. Ever at odds with one another in the temporal flow of memory, voluntary and involuntary memory continually inscribe what is effaced and efface what is inscribed.

At the turn of the last century, Sigmund Freud described a similar movement between the conscious and the unconscious mind, when he analyzed the psyche as a ceaseless churning of memory and repression. Meanwhile, Marcel Proust offered up the madeleine as the royal road to lost time, and lost sensation. Seeking the remembrance of things past, Proust strenuously placed the involuntary memory in the service of the intellect.4 Nevertheless, his novels are haunted by a language that inscribes what is effaced and effaces what is inscribed. Sensation, feeling, and memory can exist on the inside without articulation, but they exist on the outside only through articulation. Articulation is a distorting mirror, however. Consciousness and language paper over the separation between feeling and articulation but a gap exists nonetheless.

If the nineteenth-century bourgeois subject was born with a gap between feeling and articulation in its breast, then the twentieth-century Expressionists and Actionists, including Egon Schiele and Lassnig’s friend Rainer, sought a way around this separation through practices of direct expression. They howled, hurled, or otherwise broke down the self in order to express so-called primitive or primal sensations. Yet, as Arthur Rimbaud wrote in 1871, “I is someone else.”5 In the process of thinking about or depicting yourself, you actually become someone else. There’s no way around it.

Lassnig’s art seems driven by a species of existential self-knowledge: “I is someone else.” Her primary subject is herself. But she approaches her art without intentions, by which she means the desire “to paint something very specific.”6 Her artistic process is slow, concentrated, meditative. She never uses photographs. Instead, she often closes her eyes in order to see past the conventions that seeing imposes, or she lies down or sits on the canvas as she works. From “meditative slowness” comes awareness of the interior bodily sensations rendered in the strokes and lines of her art.7 Shaped by the self and shaping of the self, in Lassnig’s art visual language transforms the self into another as it transforms the self into an I. Lassnig creates and she is depicted.

In Language Grid, a self-portrait of 1999, verbal and visual language are enabling and constraining. The painting’s size and scale are monumental. The artist’s head, seemingly under construction and set against a blank field, calls to mind nineteenth-century photographs of monuments in the making—Bismarck’s head, Liberty’s torch—whose colossal dimensions would be gauged by the part as well as the whole. The way the vocal chords appear to be propped on a grid in the painting, the way this grid resembles an annotated scroll, remind me that language is a matrix or grid that enables expression. At the same time, the painting poses a contrast between the openwork of the tinker toy torso and the grid, which becomes denser and darker—more laden with paint, more somber in tone—as it reaches the throat. The grid appears then to be a grating. Like a barred prisoner’s window, it promises and disavows.

The point of contact between grid and throat is the pivot of Language Grid; the mouth is its center of gravity. The grid that supports the vocal chords appears to be the grate that heaves against them. Is the artist’s mouth open to express language or has it been forced open by discomfort, by terror, as in a silent scream? Color participates in this question and its irresolution. The construction of the face through fauve-like zones of color contrast invokes visual pleasure. Still, the color red enlivens and alarms, especially in the cheeks, where horizontal strokes simultaneously build and flatten. The syncopation of expansion and contraction in the cheeks echoes the seesaw of the throat’s grid-grate. The result is a drastic painting.

For Lassnig, drastic paintings “are those that bluntly admit that any emotion is accompanied by an image, and this union of image and emotion creates a simplicity in which reality predominates nicely, since our external life dominates the emotional life, just as the ordinary person believes.”8 In Language Grid, image-emotion occurs at the throat, where language is expressed, but it reverberates throughout the figure. The seesaw of the throat’s grid-grate, like the expanding and contracting of the cheeks, alludes to the felt points where verbal and visual language is constraining. Just as consciousness papers over the breach between feeling and articulation, so the external life—of self-perceptions, of social constructions and cultural conventions, including the conventions of art—dominates the emotional life and shifts the shape of the self portrayed.

Whereas the Viennese Actionists and the successive artists they inspired expanded their pursuit of a body-centered art into performance, photography, and video, Lassnig has persisted (even in her animated films) with what she calls the Ur-art of painting and the devices of pencil and brush.9 Drawing offers a “freer and more flexible” engagement with body sensation and body awareness than painting on stretched canvas, since the artist can place a sheet of paper, as she says, “on my knees, on my belly in bed, on the table, on the floor, on a chair,” and she “can take up all sorts of postures in front of it.”10 The drastic paintings begin with the body as an object and they depict the sensations of this condition. The drawings begin with bodily sensations and they grope toward awareness—toward articulation—of the feeling world. On both canvas and paper, the artist creates a perspective of the interior body. Background, when it does appear, does not set the figure in space; it seems to be an extension of the figure’s internal space.

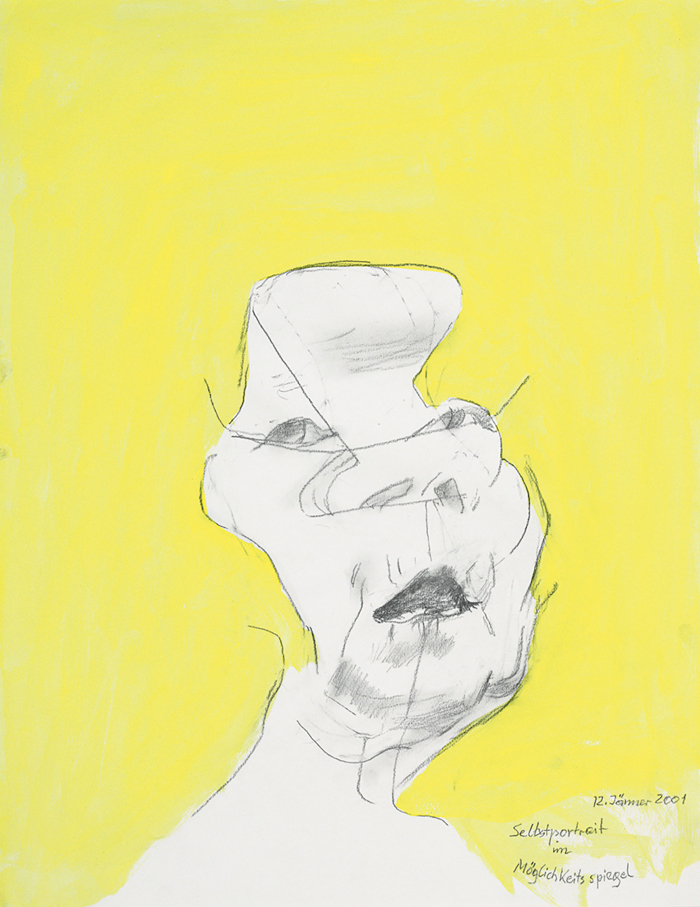

In Self-Portrait in the Mirror of Possibilities, a pencil and acrylic on paper of 2001, the primal pencil is concentrated on an originating moment of depiction. The smallness of this work draws me near. Its impact intensifies the nearer I draw. My eye travels into the mouth, into the artist’s body, as the artist’s face emerges from space the color of a bodily fluid. Just as Lassnig seems to draw from the inside out, so she appears to emerge through the paper rather than to be depicted on it. To follow her pencil is to see sensation taking the form of a provisional awareness—vague pressure drawing the eye toward the cheekbone, scent in one nostril, mental and manual concentration as a grip in the throat. Here Lassnig conjures a visual language for the process of the self becoming another as it becomes an I. A self-portrait.

Maria Lassnig, Selbstporträt im Möglichkeitsspiegel/Self-Portrait in the Mirror of Possibilities, 2001. Pencil, acrylic on paper; 645 x 500 mm. Courtesy of the artist and Museum Ludwig, Cologne. © Maria Lassnig.

Yet Self-Portrait in the Mirror of Possibilities is a portrayal of self in possibilities’ mirror. Here as elsewhere the artist must give form to feeling “because feeling has no form; it is a dissemination.”11 Lassnig describes the process of translating interior sensation into form as “fencing in clouds.”12 Her description recalls for me Walter Benjamin’s essay on a child’s view of color. Whereas “productive adults” perceive color as a discrete form or object of experience, Benjamin contends that from a child’s point of view color is an “interrelated totality of the world of the imagination,” as in a rainbow (or a cloud).13 To fence in clouds is to dissolve this interrelated totality into form—into an object of awareness, into an object for thought. Hegel similarly describes the involuntary memory as awash in figureless images, which is to say in images without a differentiating contour. Hegel, Benjamin, and Lassnig each evoke figuring as a distorting mirror, and fencing in figureless images (feeling, memory, a rainbow, clouds) cannot be done without distortion.

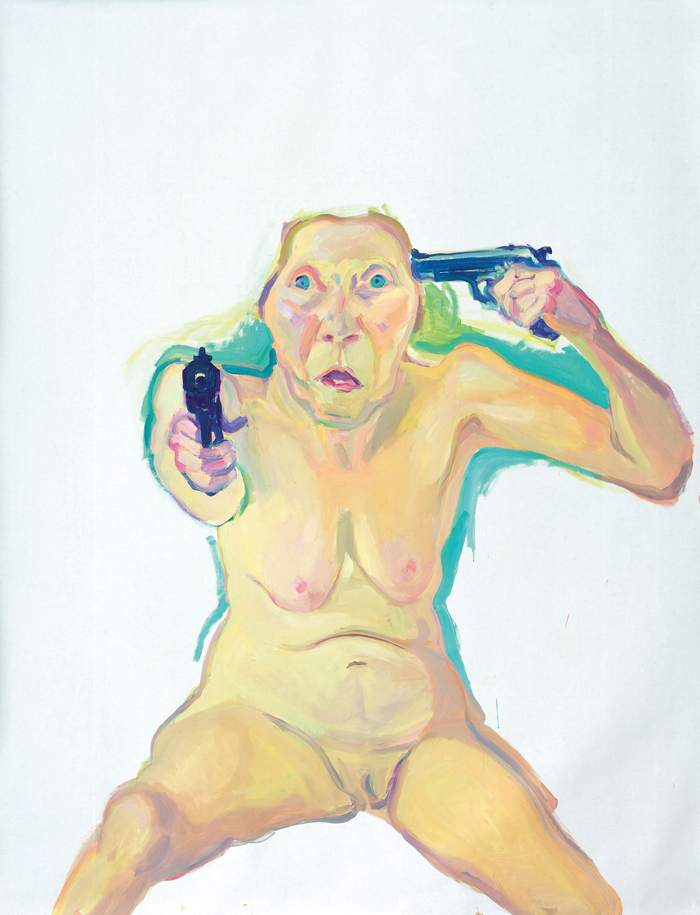

Maria Lassnig, Du oder ich/ You or Me, 2005. Oil on canvas, 202 x 155 cm. Friedrich Christian Flick Collection. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Maria Lassnig.

Lassnig’s small works on paper invoke the ebb and flow of sensation-awareness. The big drastic paintings “knock the truth on the head with a hammer.14 Nevertheless, these works of art are tuned to the same imperative. They emerge between sensation and awareness, between “I think” and “I am thought,” in the gap papered over by consciousness.15 Imagination resides in this breach. Immanuel Kant claimed that the productive imagination is an ingredient of every possible perception. In Lassnig’s art, it is. Like sensation, for her “the imagination itself is a reality.”16 Imagination lends shape; it does not fix form. “For the fact is that the imagination,” as Benjamin says, “never engages with form, which is the concern of the law, but can only comprehend the living world from a human point of view creatively in feeling.”17 Lassnig’s art is the comprehension of the living world from this perspective and the creation of a visual language for its depiction.

In You or Me (2005), a drastic painting if there ever was one, the artist straddles the gap. A gunslinger naked and nude, herself and herself as another, she takes aim at the interior and exterior world. You or Me invokes comment on the objectification of women. But the breach it suggests drives deeper still. In You or Me the artist hits the truth on the head with a hammer. For the truth is, body sensation and body awareness are two separate things nonetheless bound together.

Karen Lang is associate professor of art history at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. A recipient of numerous fellowships and awards, she is the author of Chaos and Cosmos: On the Image in Aesthetics and Art History (Cornell University Press, 2006) and essays on a range of topics.

For Ursula, Christian, and David