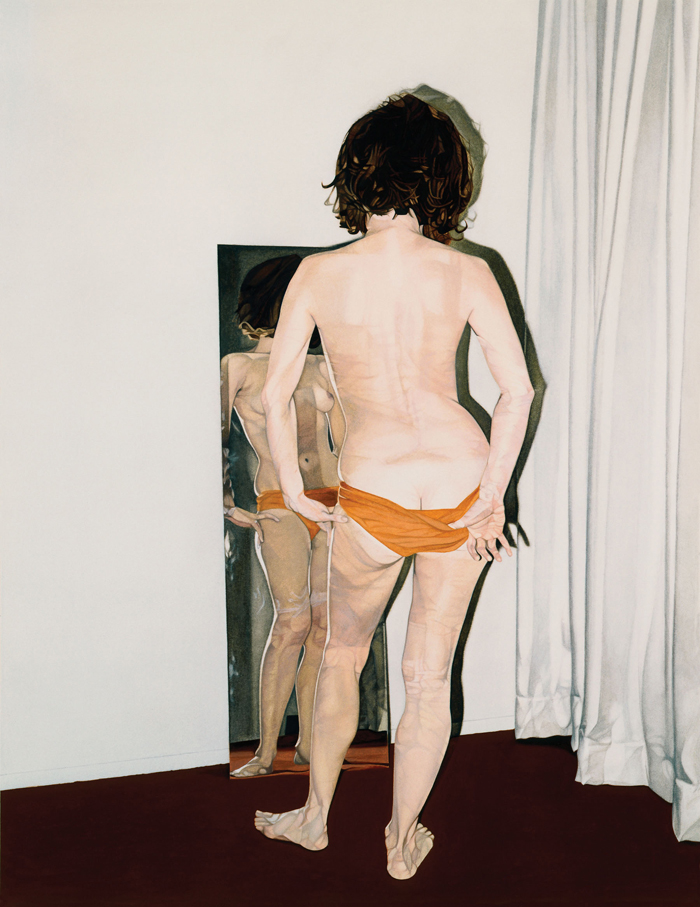

Judie Bamber, Mom With Orange Underpants, 2006. Watercolor on paper, 16 1/2 x 12 3/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Angles Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

In 1871, James Whistler’s portrait of his mother was nearly rejected from a show at the Royal Academy of Art when the academy objected to its title: Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1. Whistler, who disavowed the significance of his model’s identity, appended the explanatory subtitle, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, merely to mollify his Victorian critics. Judie Bamber’s portraits of her mother, which appeared in Are You My Mother? at Angles Gallery, can be thought of as arrangements of color, light, desire, and emotion. While Whistler made his mother central to his investigation of grayness, and subordinated her to a rigorous formal structure, the mother almost bursts out of Bamber’s tidy compositions, brimming with life and bristling with sexuality. And while the visual trope of “mother and child” is overly familiar, the presentation of the mother alone—the mother with a book, a balloon, with tan lines, the mother looking at herself in the mirror, the mother playing erotically to the gaze of the artist—these cross the line between an almost religious reverence and potentially incestuous voyeurism.

With these diminutive paintings and drawings, Bamber seems to reach back in time, as if to find the woman before she was “the mother,” before she had taken on the stereotypic maternal function in relation to the artist. To access this time, Bamber used photographs taken by her father, in most cases photographs where the mother knowingly poses for his camera. Bamber precisely reproduces these photographs in graphite and watercolor, and transforms them in the process. The transformations are subtle but stunning—what a photograph flattens out, say a shadow, the graphite deepens. What a photograph lends perspective to, say a reflection, the painting renders as superficial.

In fact, the transposition of surface and depth alters our understanding of the “arrangement” of desire between mother, father, and child. Bamber’s work investigates the similarities and the differences between not only the mother and the daughter who paints her, but also between the father who took the photographs and the daughter who reproduces them. Through her painstaking absorption in recreating these images, Bamber brings herself into direct relation with these people—her parents, who apparently folded images and image-making into their own sexual pleasure. Bamber clearly identifies with their enjoyment in looking (and in being looked at), as if to claim kinship across the abyss that separates parents and children.

Bamber thus interrupts the neat symmetry of the expected Oedipal triangle that demands the girl desire the father and identify with the mother. These paintings exhibit both identification and desire, yet they exceed that binary and conjure the maternal body as the epicenter of its own aesthetic universe. In so doing, Bamber undoes the voyeurism implicit in her father’s photographs, and re-configures the image of the mother from an object to be looked at, to an aesthetic subject who herself looks, desires, arranges the gaze, and even looks away. The transition from photograph to painting draws out the sexuality of the mother’s looking even as it disperses that sexuality across the canvas and away from its sole focus on the female body.

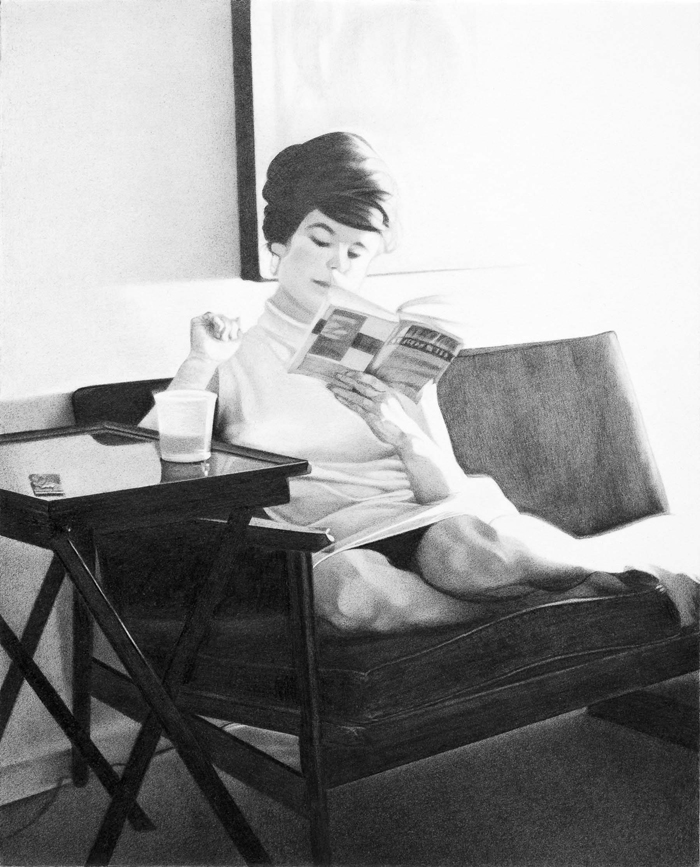

Judie Bamber, Mom Reading 1, 2010. Graphite on archival board, 10 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Angles Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

In one graphite drawing, Mom Reading 1 (2010), the female figure sits on a narrow modernist sofa, a drink at hand, legs curled under her and with her eyes down, absorbed in her book. She is marked as “mom” by the title, yet the woman here contradicts our everyday expectations of motherhood: time is in abundance, leisure absorbs her, and she has literally composed herself as part of the modern décor; she seems calm, in control, apparently defying the decomposition that is associated with motherhood. If being a mother tethers the woman to the child’s schedule—to her needs, whims, fits, and moods—these portraits refuse to allow the sitter’s subjectivity to be colonized by these expectations. In this portrait and in others, the sitter turns away from the gaze of the artist, the photographer, or the viewer, and is occupied elsewhere; she sets herself apart and disappears into the other universe of the book. In Mom Reading 2 (2010), the woman emerges from her book and turns to face the viewer. The gaze here is a direct, forthright, and even sexual, and Bamber’s detailed drawing emphasizes the way the photo catches the body in motion as the figure reaches back to scratch an itch, answering its own needs rather than the needs of an other, emphasizing the body’s presence as experience rather than object.

Judie Bamber, Mom Reading 2, 2010. Graphite on archival board, 8 x 10 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Angles Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

By reframing these two photographs and others in the exhibition as autoerotic, Bamber draws out the subject’s engagement with her own image, her self-conscious self-presentation for the camera. By disrupting the heterosexual circuit of looking, Bamber turns our attention back onto the woman, and from there back to the female artist who paints her, and finally to the act of painting itself. Bamber’s mother thus becomes a mirror for her daughter not because both are caught in the act, trapped in the frame, but because the narcissistic interaction between the mother who composes herself and the daughter who paints her doing so creates a dialogue on gendered creativity itself. The daughter removes the mother from the clichéd erotic structure of the pinup and places her firmly within an aesthetic structure, a structure that is itself eroticized by the intensity of Bamber’s looking and meticulous transcription of the images.

Frames abound. In two other images, one graphite and one watercolor, the figure looks into a mirror and manages her self-image there. Mom with Tan Lines #1 (2007) teases the viewer by showing the mother naked from behind and emphasizing her breasts and butt by revealing the tan lines that cordon off these private areas from public consumption (another frame). The angle of the image allows us to see her face in the mirror propped on the bed, but not the rest of her body. The woman, like the bed upon which she sits, is disheveled despite the neatness of the tan lines and the tidiness of the pose, and her expression in the mirror is thoughtful, as if she is critically considering her own body as an image and object.

In Mom With Orange Underpants (2006), the mother’s body is framed by a kind of theatrical set up—stage, mirror, curtains— and the “actress” at the center of the frame looks into a mirror that casually leans against the wall. Smudges on the mirror serve as a reminder of the artistic process of leaving human marks on surfaces. And the woman’s pose, pulling at her “orange underpants” while looking at herself, creates tension between showing and hiding, exposing and concealing, recognizing and mis-recognizing, a tension that extends through all the work here. Again, the woman’s attention to her own body and her own clothing seems to imply an intimate viewer, who watches openly, but in the transition from playful photograph to the meticulously rendered painting, the implied heterosexual male viewer is replaced by the queer artist, and what perhaps was a naughty gesture in the photograph becomes an aesthetic intervention in the painting.

Ultimately, Are You My Mother? questions not simply the status of intimate relations and aesthetics, it also wonders about scrambled circuits of desire that compose and decompose across time and space and make the mother into more of a question than an answer, more of a mystery than a source of comfort, more of an artist than an object of the gaze. Bamber’s portraits of her mother taken from her father’s photographs are not simply “arrangements” in color or black and white, they are re-arrangements of kinship, of family, desire, and identification. And if you look closely enough at the rendering of shadow and light, the transformation of print into canvas, of light into paint, you can find multiple answers to the question that frames the show.

Jack Halberstam is Professor of Gender Studies and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. Halberstam is the author of four books, most recently, The Queer Art of Failure (Duke UP, 2011), and has a fifth book coming out in September 2012 titled Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender and the End of Normal (Beacon).