Work (Water) (1956) by Motonaga Sadamasa (1922–2011) was made of plastic tubes of varying diameters and lengths, sealed at each end, and weighed down in the middle by quantities of colored water. Photographs of the work strung between trees in the Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition of 1956 suggest sci-fi pods in a transforming landscape, membranes from which something alien might emerge. The sight of Work (Water) at the Guggenheim, its elegant swoops crisscrossing the rotunda, signaled three things: first, that the curators of Gutai: Splendid Playground, Alexandra Munroe and Ming Tiampo, were not pussyfooting around when it came to the refabrication of no longer extant works, but neither were they trying to replicate the works’ original contexts; second, that Gutai’s strange, organic futurism was being put in dialogue with a more familiar modernism; third, that surfaces—membranes, skins—were something that demanded attention.

Motonaga Sadamasa, Work (Water), 1956. Polyethylene, water, dye, and rope; dimensions variable. Installation view, Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition, Ashiya Park, Ashiya, July 27–August 5, 1956. © Motonaga Nakatsuji Etsuko. Courtesy Motonaga Document Research Office.

Gutai was a self-consciously avant-gardist association of artists, based in Osaka and presided over by its founder, the painter Yoshihara Jiro (1905–1972), who determined its membership. It is seen to have had two phases, the first, 1954–61, more concerned with radical self-expression (the “pure creativity” Yoshihara called for in his manifesto of 1956)1; the second, 1962–72, modifying its existentialism in favor of engagement with technology and a broader audience.2 These distinctions are somewhat approximate, of course. Perhaps the most iconic work produced by a Gutai artist, Electric Dress (1956) by Tanaka Atsuko (1932–2005), a “dress” of flashing, painted light bulbs, made during the first phase of Gutai, clearly deals with technology. Shiraga Kazuo (1924–2008) and Shimamoto Shozo (1928–2013) continued to refine their unusual ways of making paintings after 1961, while Matsutani Takesada (b. 1937) added to the corpus of painting in Phase Two. Still, it seems that Phase One more often anticipated aspects of Phase Two than Phase Two developed or transformed ideas from Phase One. And, while Phase One produced many abstract paintings that may be appropriated to existing historical categories, its overall effects are the more unsettling over time.

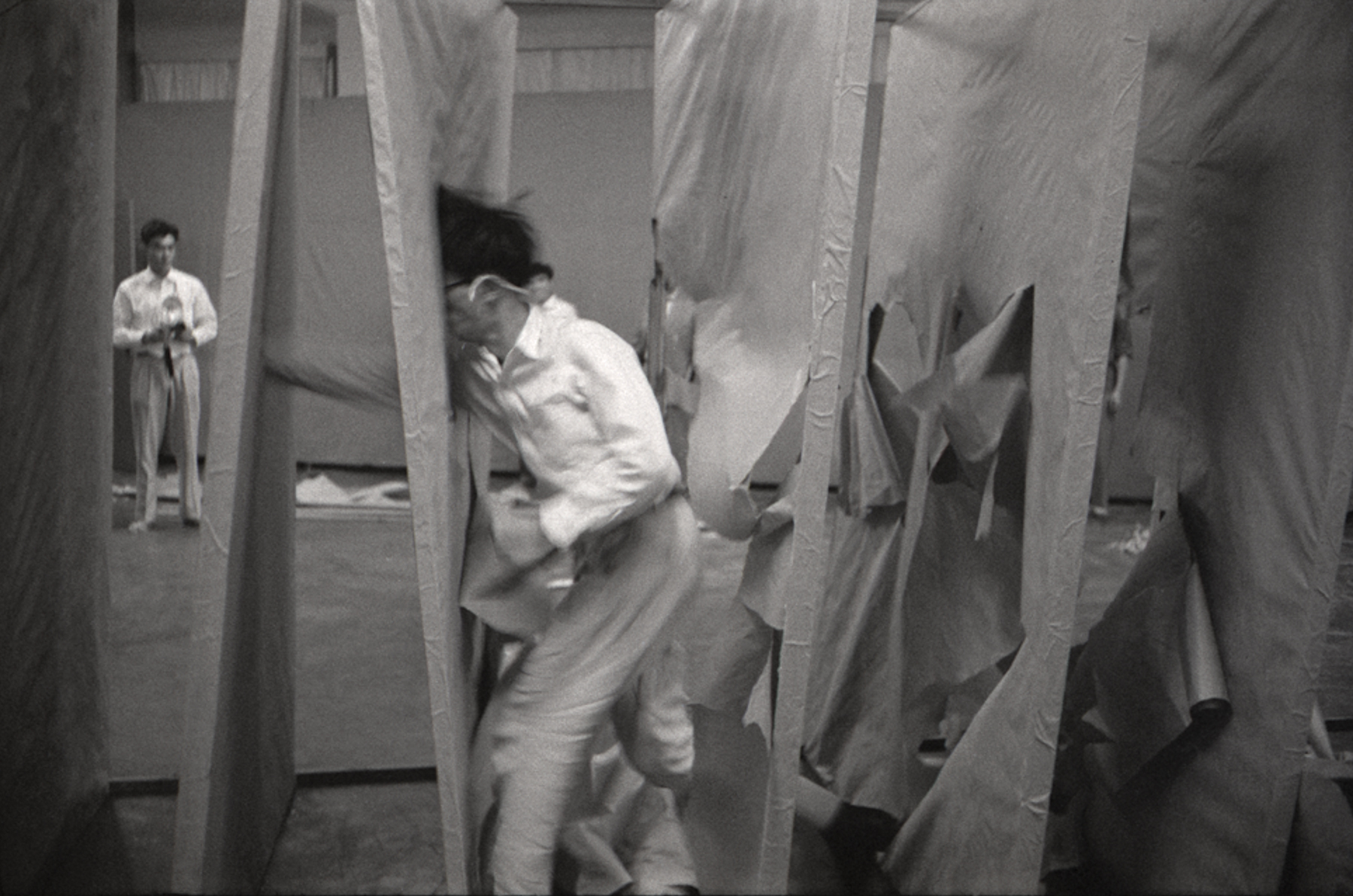

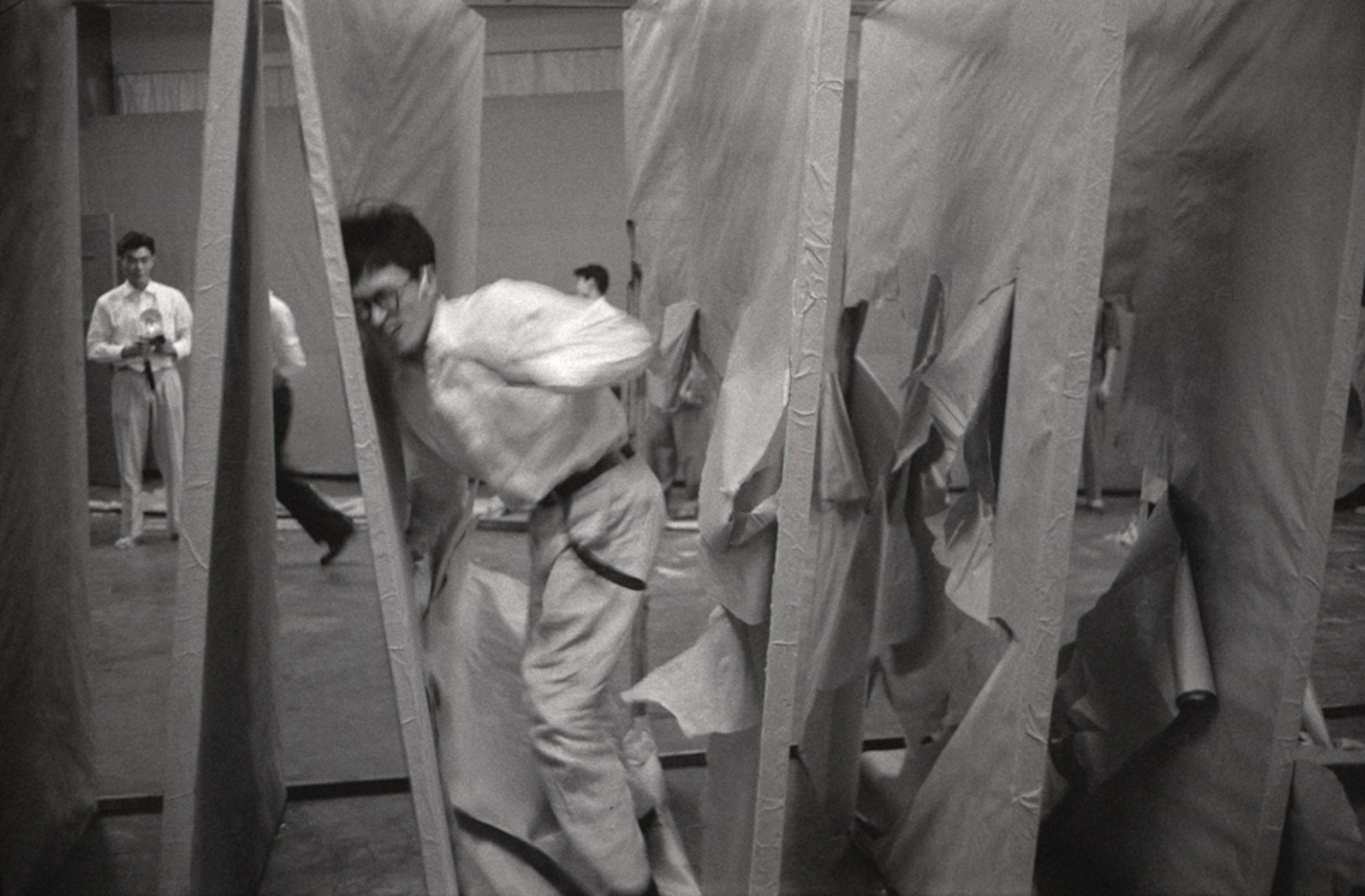

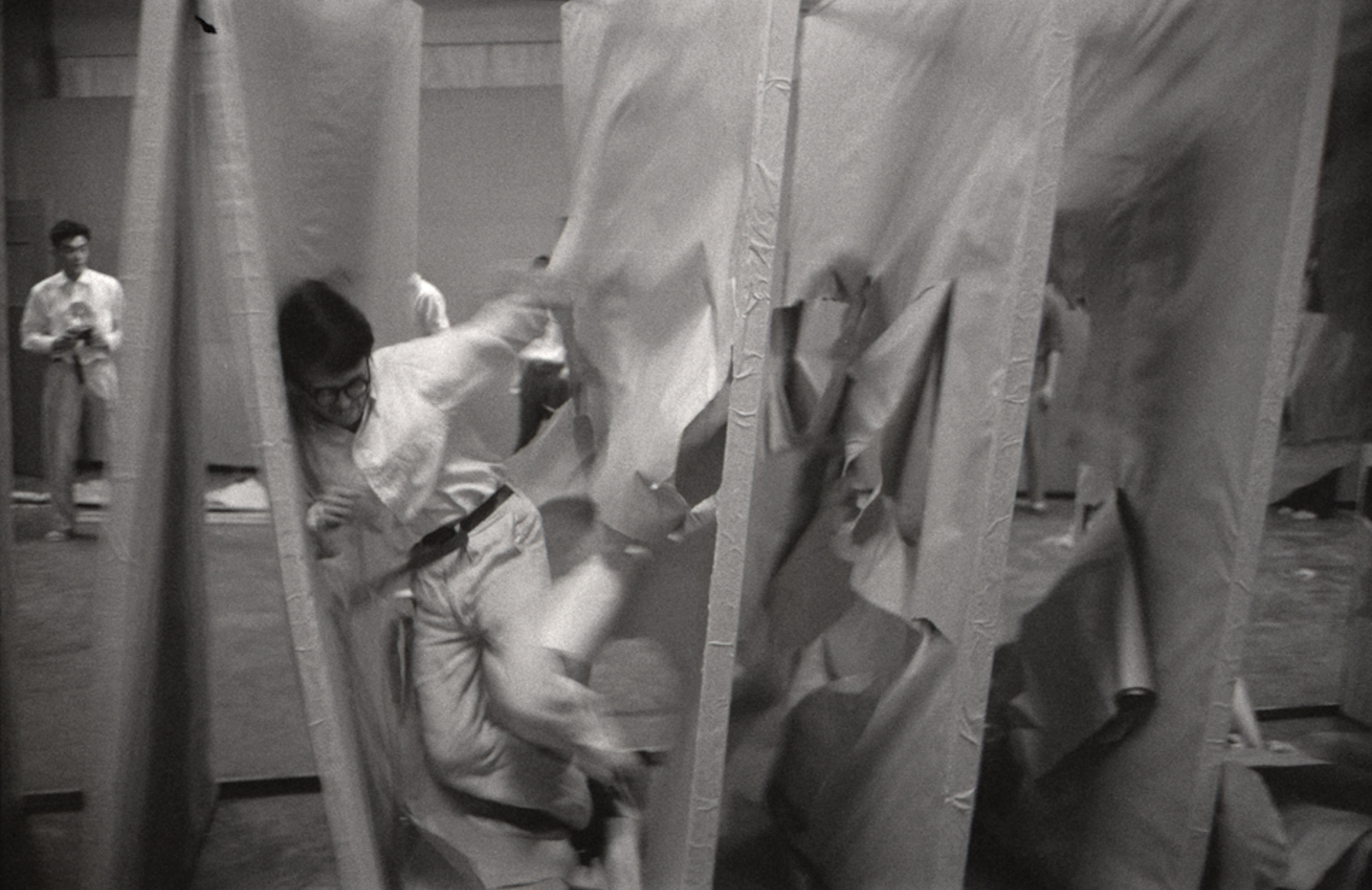

Shiraga Kazuo demonstrating his signature painting style during the 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition, Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo ca. October 11–17, 1956. Photo: Otsuji Kiyoji, Collection of Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo. © Otsuji Seiko.

Gutai artists produced a wide variety of works, many of them performative or otherwise ephemeral, and key works no longer exist, including Work (Water), Electric Dress, and Work (Red Cube) (1956), by Yamazaki Tsuruko (b. 1929), a red vinyl room-like enclosure, suspended about two feet off the ground by cables, also originally seen outdoors. (Work [Red Cube] seems to resonate with later architectural interventions such as Bruce Nauman’s Floating Room of 1972, though the exhibition suggested such different motives that it rendered many such connections tenuous at best.) The exhibition catalog largely documents original works in their initial settings—Yoshihara and his cohort were canny about documentation, even staging the One Day Only Outdoor Art Exhibition on April 9, 1956, for the benefit of photojournalists from Life magazine3—but a number of refabricated works were exhibited without fuss. (Where other efforts at reconstruction or the redo have generated a frisson of approval/disapproval—usually to do with the relation of the reconstruction to the artist’s intentions, the original context, and notions of authenticity—this is evidently less compelling in the case of historical or unfamiliar works.) In Gutai: Splendid Playground, along with vitrines of photographs documenting the original installations of works that have disappeared or decayed, there was something about the shiny new versions that helped to undercut the sacral high modernism of Wright’s ramp and rotunda. The frank acknowledgment of ephemerality tied to the newness of the version of Work (Water) on view, for instance, along with the work’s playfulness—the old-fashioned, space-age aspect of the curving plastic pods, together with the child-like quality of the brightly colored water—suggested a different, temporary, contingent, and unmonumental modernism.

Gutai: Splendid Playground, installation view, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 15–May 8, 2013. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Of course, something similar might be said of Happenings, as developed in the United States and Western Europe. A fairly standard response to Gutai has been to see it as a derivative—or at best counterpart—first to abstract expressionism and then to Happenings. As a result, Gutai is still described as having produced the strongest second generation of abstract expressionists.4 Munroe and Tiampo thoroughly discredit this approach. The exhibition and in more detail the catalog track relations between Gutai and American and European abstraction, Happenings, art informel, Tachism, intermedia, Gruppe Zero and the Nul group, and it’s clear that these were not one-way streets. (In this context, it’s not clear, for example, exactly when in the fifties Allan Kaprow encountered Gutai.)5 Yoshihara had a sophisticated understanding of what we would now call globalism and of center-periphery relations, in which the periphery—or the region (Osaka as against Tokyo)—was seen to be a “freer, more experimental space than the art world’s centers, whose power actually endorsed conservatism.”6 Certainly, Yoshihara and his followers were interested in Pollock, as was Kaprow, but to see their work as continually secondary is to ignore differences in historical context, and to invest in false morphologies. This is where the importance of skin emerges in Phase One Gutai, perhaps especially skin in relation to technology.

Shiraga is one of the artists to whom one might point for the direct influence of Pollock. Famously, he painted with his feet, either standing and sliding around on long sheets of paper (subsequently mounted on canvas), or swinging from a harness with his feet down. This process can be seen, not unreasonably, to develop the gestural or performative interpretation of Pollock’s process, as though emphasizing or elaborating the idea that Pollock was “in” the canvas (in a way that Pollock, eternally leaning over his canvases in Hans Namuth’s photographs, never really was). But the more you look at Shiraga’s paintings, the more distant Pollock becomes as a point of departure. To start with, foot-painting is even more pre-symbolic than the finger-painting that we typically associate with children, and Shiraga’s paintings of the late fifties, like Work (1957) and Work II (1958), are fabulously crude, kinetic knots, with none of the delicate, filigreed layering of Pollock’s work. And in the video documentation situated near his paintings in the exhibition, Shiraga at work looked gleeful in a way that is difficult to associate with Pollock. In Challenging Mud (1955), performed in Tokyo at the 1st Gutai Art Exhibition, Shiraga plunged half-naked into a large pile of mud, thrashing around and wrestling it as best he could. His paintings deal with paint as if it were mud, a material substance. To distinguish between paint as a “substance” and paint as a“medium” is to acknowledge the ways that mediums invoke the history of the artistic manipulation or deployment of the substance. While the Gutai artists knew their art-historical precursors, their futurism required them to set that aside, at least to some degree. To this end, Shiraga put his skin directly against the paint and paper. In Wild Boar Hunting II (1963), Shiraga intensified this skin-on-skin aspect of his process by painting with his feet on a boar’s hide, to produce a dense, visceral surface at the center of which is a vivid red slash of thick paint: a wound.

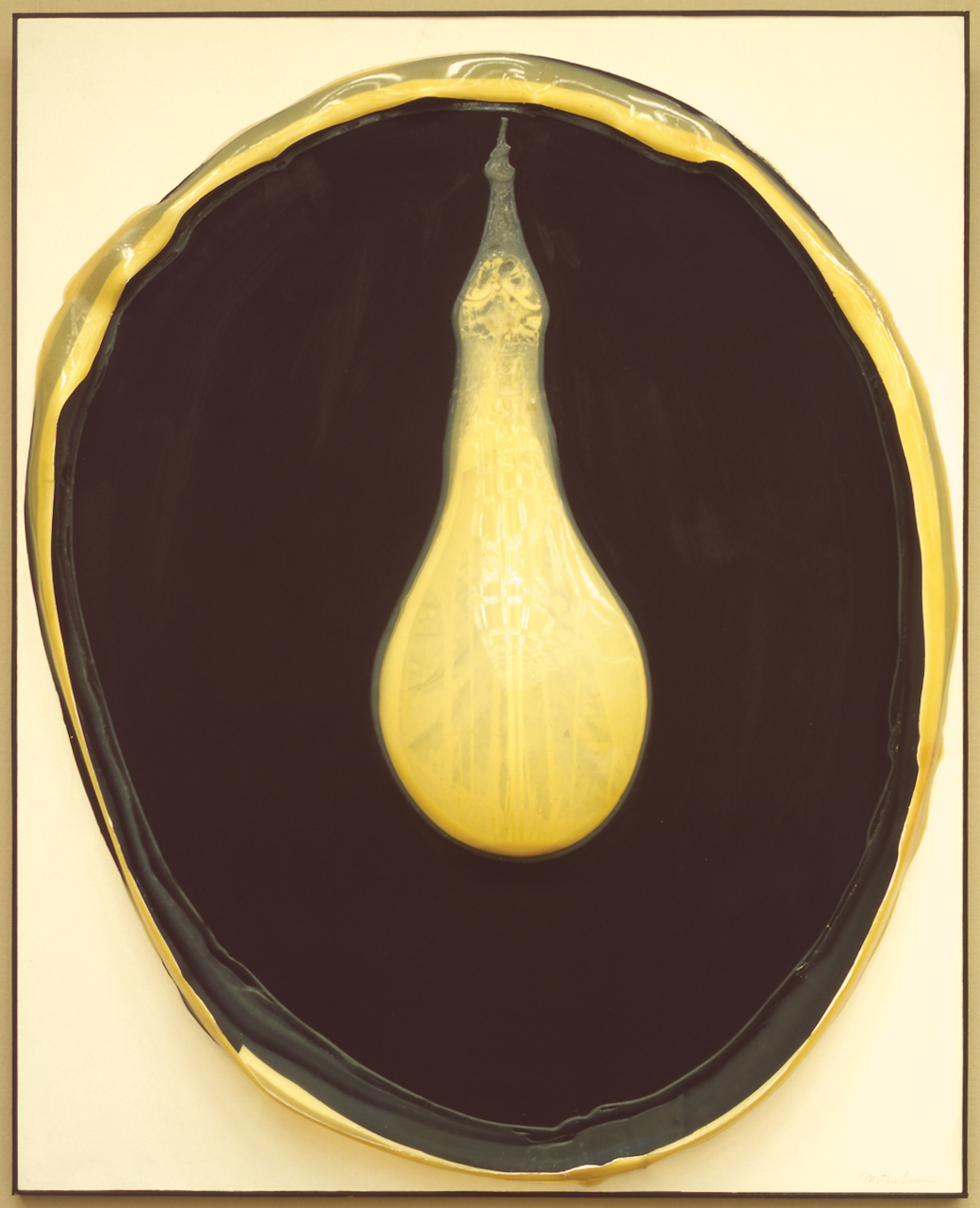

Matsutani Takesada, Work, 66–2, 1966. Synthetic paint and adhesive on canvas, 63 1⁄2 × 51 × 4 3⁄4 inches. The Miyagi Museum of Art, Sendai, Japan.

A similar mix of play and damage or destruction involving surface or skin can be seen in other paintings. Shimamoto made paintings by hurling glass bottles of paint at canvases. That shares in some of Shiraga’s glee, while Kanayama Akira (1924–2006) was more coolly mischievous, using automated devices modified from electric toy cars to make spidery, all-over compositions that are the closest things to Pollock in the exhibition, but which, as in Work (1957), threaten to become so dense that all their lines will finally congeal, or even rupture the surface. Matsutani is represented in the exhibition by two extraordinary Phase Two paintings featuring circles (a motif that Yoshihara himself had adapted from traditional Japanese art), White Circle (1966) and Work 66-2 (1966), from which emerge thick yet fragile-looking translucent blisters, in rounded shapes that seem to refer to body parts (breasts and/or penises). It turns out that the blisters were formed by inflating a “synthetic adhesive,” i.e. Elmer’s glue. As with Kanayama’s little machines, there’s a lo-tech sci-fi quality to these, accompanied by a sense of possible collapse.

The complex of play, skin, and destruction is not restricted to painting. It is also seen in the performances by Murakami Saburo (1925–1996) in which he crashed through large sheets of paper stretched across wooden frames, which suggest both paintings and the screens of traditional Japanese architecture. In Passing Through (1956), performed at the 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition in Tokyo, Murakami broke through twenty-one screens, ending up with a concussion.7 At Gutai Art on the Stage in Osaka in 1957, Kanayama exhibited Giant Balloon, which in documentation looks to have drawings on it, and is reminiscent of nothing so much as The Blob from the eponymous 1958 American movie— a monster connection that for me can’t help but in turn conjure up Japan’s own nuclear mutant monster, Godzilla, who first appeared in 1954. Kanayama would later make the 16 mm film Circle (1970), in which a very long, pink, helium-filled balloon marked out a circle in a landscape. Kanayama’s balloon works are funny, but at the same time, the industrial-scale balloons seem bound in the end either to explode, or sag: his Balloon (1956), seen in a photograph of the Nul 1965 exhibition in Amsterdam, has a comical, deflating pathos.

Murakami Saburo, Passing Through, 1956. Performance views, 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition, Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo, ca. October 11–17, 1956. Photo: Otsuji Seiko Collection, Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo. © Otsuji Seiko and Murakami Makiko. Courtesy Musashino Art University Museum & Library. Photo: Otsuji Kiyoji.

These relations are brought to a head in Tanaka’s Electric Dress. The “dress” of flashing light bulbs is another low-tech, sci-fi object, an impression that is especially reinforced seen in moving image documentation, flickering in the dark, when it can seem both mysterious and menacing. The dress is heavy and hot: not only must prolonged wear have been uncomfortable, it must also have been dangerous (it might burn, explode, catch fire): the technological armature that produced the spectacular image of the artist as a kind of dancing robot was simultaneously potentially harmful. This is a work that I would situate in a dialogue with Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964). At the end of her performances, Ono was left naked or nearly naked, surrounded by shreds of clothing: metaphorically, this placed a Japanese woman’s body at the center of a scene of destruction, in the wake of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (and also in the context of the Vietnam War).8 In relation to this, wrapped in technology that is at once spectacular and dangerous, Tanaka in Electric Dress is a robot dancing in the ruins. The idea of a dialogue with Cut Piece is only strengthened by Tanaka’s own “striptease,” in Stage Clothes (1957), a performance in which Tanaka rapidly unwrapped herself from layers of clothing, which look as though they begin with more traditional forms, as if to emerge in post-nuclear Japan in a fully modern and functional skin-tight black outfit. Subsequently, Tanaka’s paintings of circles connected by lines— including the large-scale ephemeral drawing with a stick on the beach seen in the film Round on Sand (1968)—relay her interest in systems and networks, but also suggest cellular forms, so that the Drawing After Electric Dress (1956), for instance, intimates an interweaving of technology and the body.

There is little in the exhibition that seems to speak directly to nuclear destruction, even though many of the Gutai artists were born in the 1920s and must have been acutely aware of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yoshida Toshio (1928–1997) made works like Work (Burn by CF No. 8) (1954) by branding wooden surfaces with hot coals, which recalls the terrible, burnt-in shadows of the bombed cities, and one might construct an argument about the distressed surfaces of other Phase One paintings. Yoshihara’s emphasis, followed by Munroe and Tiampo in the catalog, was on “pure creativity” as a means of countering Japan’s history of totalitarian rule, as if the free exercise of individuality would serve as preparation for democratic living (if only…). This is the ethical dimension of Gutai’s insistence on play. Not being steeped in the interior world of Gutai, or in the social psychology of post-nuclear Japan, however, it is difficult to encounter the various forms of skin in the exhibition—from Motonaga and Kanayama’s plastic membranes, to Shiraga’s flayed boar hide, to Tanaka’s electric armature—without seeing them as ways of imagining the body, and existence itself, transformed by the bomb. Nuclear fission, after all, seems like another way of understanding “the scream of matter itself,” which Yoshihara valued in the work of Pollock, if also Mathieu.9 Like Gutai, Godzilla the mutant dinosaur might be funny, but he’s no joke, and the ethics of play are not undercut by Tanaka’s dancing robot. It’s just that the work of Tanaka and the other artists recognizes that the dropping of the bomb is irrevocable, and that its ramifications are uncertain, even mutant, that it changes even the possibility of imagining “the unknown and original world,” the tabula rasa of Yoshihara’s manifesto.10

Tanaka Atsuko, Electric Dress, 1956 (refabricated 1986). Synthetic paint on incandescent lightbulbs, electric cords, and control console; approximately 65 × 31 × 31 inches. Takamatsu City Museum of Art, Japan. © It Ry ji. Courtesy Takamatsu City Museum of Art.

This recognition is not posited as traumatic, though. Early in her Gutai career, Tanaka exhibited the cool-as-a-cucumber Work (Yellow Cloth) (1955), three pieces of commercially produced yellow fabric, hung like paintings, their edges here and there almost imperceptibly cut and reglued. It’s a neat Duchampian recontextualization that seems to preempt Daniel Buren’s early striped works, with the last white edge painted, except that Tanaka was engaged with seeing things differently, rather than reflecting on the conditions of seeing. In a similar vein, Murakami’s All the Landscapes (1956) was a picture frame, hung from a tree. For some of the Gutai artists, perhaps, to dance in the ruins was to look out into an irrevocably new world.

This makes sense of the Phase Two enterprise of trying to reach a broader public by means of an engagement with technology. A number of geometrical paintings and shallow reliefs produce optical effects; some, like Work (1966) by Imanako Kumiko (b. 1939) or Work 2-7-67 (1967) by Kikunami Joji (1923–2008), use materials such as metal and Plexiglas, though these lacked the brute perceptual charge of some of their global counterparts. A higher-tech sci-fi aesthetic is in play, most obviously in Bisexual Flower (1969) by Yoshida Minoru (1935–2010), an elaborate, motorized, Plexiglas and neon bachelor machine. These tend to suffer a little in relation even to other Phase Two works by older artists, such as Kanayama’s Circle, by virtue of their self-contained sleekness. Perhaps by the mid-sixties the new was taking a recognizable shape that curtailed the experimental playfulness of earlier Gutai.

Nasaka Senkichir and Yoshihara Michio, Work, 1970. Stainless steel pipe and recorded sound, approximately 492 feet long. Installation view, Gutai Group Exhibition, Midori Pavilion, Expo ’70, Osaka, March 15–September 13, 1970. © Nasaka Senkichir , Yoshihara Naomi and the former members of the Gutai Art Association. Courtesy Museum of Osaka University.

Gutai’s participation in the Expo ’70 world’s fair in their base, Osaka, made the strongest case for Phase Two’s changed direction, as Gutai produced urban environments in a mass-cultural context. Gutai artists were involved in several group installations and individual Gutai artists also exhibited their works. Gutai contributed a group installation in the Midori Pavilion featuring optical, high-tech works suspended from what was really the most interesting piece: Work (1970), by Nasaka Senkichiro (b. 1923) and Yoshihara’s son, Michio (1933–1996). Through this 150-meter installation of aluminum pipe could be heard, here and there, a sound work by Yoshihara Michio. But this reflexive presentation design was produced within the framework of the capitalist exhibitionary context: historically, world’s fairs exemplify the transformation of avant-garde gestures into R&D for corporate modernity. Similarly, the intermedia extravaganza, Gutai Art Festival, at the Expo plaza, recast earlier Gutai stage works as public spectacle. Yoshihara’s death in 1972 brought an end to Gutai, but Expo ’70, perhaps unsurprisingly, saw their last collaboration. By then, the dream of democracy fueled by freely creative individuals had given way to the discipline of the market. Even Godzilla would mutate into a franchise.

Frazer Ward is associate professor in the Department of Art at Smith College. He is the author of No Innocent Bystanders: Performance Art and Audience (Lebanon, NH: Dartmouth College Press/University of New England Press, 2012).