Pandora1 meets Amazon2 for the artworld. That’s the entire elevator pitch for Artsy, which leaves us with plenty of time to spare. When the elevator doors finally open onto the twenty-fifth floor of the Artsy headquarters, it is clear that the pitch was a success. A black ping-pong table, scattered mid-century couches, and a long, gleaming communal table lead to an open floor plan. The rare standing wall is glass and frames offices that convey transparency. The largest area is dedicated to a few dozen staffers who sit across multiple rows—each young face glowing from the LEDs of Apple flat panel displays. They are the labor force behind the startup that aims to centralize art collecting and education under a single taxonomy called the Art Genome Project.

João Enxuto and Erica Love, Artsy Office, New York, NY (8/13/14, 6:18:20 PM), 2014, photograph. Courtesy of the artists.

The Artsy offices are perched in a pre-war tower on Broadway in Lower Manhattan over mostly low-slung tenements and cast-iron buildings. There are commanding views from windows that frame a panorama of the Metropolis. This vista seems extravagant for a company that operates as a data-driven Internet platform, where eyeballs are locked on computer screens at all times. On its website, Artsy is described as “an online platform for discovering, learning about, and collecting art.”3 We visited in early August, for a Friday evening happy hour dedicated to recent college graduates. It was a party to facilitate networking among Millennials interested in art, technology, free beer, and job prospects. In many of its job postings, the company proclaims that it wants “to change the world.”4 By the end of that Friday evening, chances are that a few idealistic candidates were swept up in the exuberance.

Changing the world has long been a Silicon Valley directive, repeated by countless venture capitalists, CTOs, and developers, with usage roots possibly reaching back to some 1970s Mountain View garage-cum-laboratory littered with circuit boards and dog-eared copies of Atlas Shrugged. The mantra appeared again in the closing passage of “Here’s to the Crazy Ones,” a free-verse poem at the center of a 1997 advertising campaign that marshaled Apple’s comeback:

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. But the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things… Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.

Changing the world also requires outpacing the competition. For Artsy this will mean claiming status as the primary Internet portal between a collector and art. Recent history has proven that the network effects and power laws that rule the Internet can foster diversity, but ultimately the tendency has been toward the creation of monopolies. The “old inequities that we hoped the Internet would overthrow are often intensified,” explains filmmaker and writer Astra Taylor in her recent book, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age.5 As Taylor points out, we have “one leading search engine (Google), one major bookstore (Amazon), one predominant market (eBay).”6 Could a single player also emerge to dominate the online market for fine art?

Artsy was launched in October 2012, and has since cataloged nearly 200,000 artworks by 25,000 artists represented by galleries, museums, auctions, and art fairs.7 That’s an impressive haul for a startup working in a crowded market to solve how to most effectively monetize art on the Internet. In April 2014, investors poured $18.5 million in capital to help distinguish Artsy from Google Art Project, Artstor, Artnet, Artspace, Artstar, Paddle8, Contemporary Art Daily, Mutual Art, Christie’s LIVE, and Sotheby’s.8 Each of these platforms (which include for- and not-for-profits) provides one or more service that overlaps with what is currently available through Artsy.

Arno Rafael Minkkinen, Self-portrait from the Shelton Hotel Looking East, New York, 2005. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 24 inches. Edition of 25. Courtesy of Robert Klein Gallery. Screenshot, Artsy.net, August 8, 2014.

The Artsy headquarters in New York is a hub for art specialists and gallery liaisons in Los Angeles, London, Munich, Berlin, and Hong Kong, a total of seventy employees worldwide. From its roost high above Broadway, it is possible to survey the local datascape of confreres and competitors. Paddle8 is a mile to the north on Cooper Square. A few blocks east from there is Artnet. A pit stop at NEW INC, the New Museum’s technology incubator, is a minor detour on a stroll that concludes at Artspace, situated on the southern tip of the island. In fact, it is possible to walk the art world’s own “Silicon Alley” without ever venturing north of 14th Street.

From the Artsy office windows one can register a broad expanse of urban topography marked over time by a sequence of industries, not least of which was the visual art sector that drove the repurposing of the post-industrial city and prepared it for gentrification.9 The east-facing view is of the disorderly patchwork of Chinatown and the Lower East Side. Further still, beyond the bridges and rising waterfront condominiums, are the former and current artist enclaves of Williamsburg and Bushwick. The view encompasses the homes, studios, and home/studios of thousands of artists (including us) who are the base for art production in the metropolis10—the first step in a supply chain.

A Google web search of “Internet art sales” produces dozens of results that seem to confirm the increasing success of online art commerce. For instance, a Reuters article from April 2014 claims that the fine art market online was expected to more than double to $3.76 billion in the next five years.11 These projections were sourced from a British company that sells insurance for luxury commodities. A few weeks later The New York Times had similar news to report with “Art Makes a Move Online.” This time the data came from the European Fine Art Foundation, which runs an art, antiques, and design fair in the Netherlands and recently launched a mobile app. They reported that online sales of art in 2013 represented only 5 percent of the $65.9 billion in global sales, but projected an increase of roughly 25 percent each year for the next few years.12 In both cases, the Internet foreshadowed its success with young people and first-time art buyers willing to part with thousands of dollars on the promise of a JPEG.

The rise of the Internet and screen as the apparatus of image circulation has undoubtedly produced qualitative shifts in the art object as it moves through emerging networks. Changes in the reception and distribution of visual art has and will continue to offer rich material for contemporary art historians. What is most pressing are the political stakes in this moment of technological rupture and realignment of power.

In the matter of a few years, Evgeny Morozov has emerged as the most prolific and acerbic critic of Silicon Valley utopianism, which he argues corrupts notions of democracy with an “endless glorification of disruption and efficiency.”13 Morozov contends that the new technocrats apply what he calls “solutionism,” the use of algorithmic regulation to address the effects of political problems, such as income inequality and national security, without an understanding of underlying causes.

In keeping with Morozov’s analysis, a significant margin of error and some degree of skepticism should be brought to any forecast of art market trends linked to the Internet. The art business is the largest unregulated market in the world. Wealth distribution is very unbalanced, even among its stakeholders. There are a small number of dominant galleries, collectors, and auction houses, then there is everyone else. The art market is less a monopoly than an oligarchy. And a significant part of that inner circle has put its faith in Artsy. Additionally, a link from Artsy to Silicon Valley has been engineered through the financing of PayPal co-founder and venture capitalist Peter Thiel, Pandora CEO Joe Kennedy, Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey, and Google Executive Chairman and former CEO Eric Schmidt, among others.14

Origins

Hatched in the Ivy League dorm room of its future CEO Carter Cleveland, the origin story for Artsy echoes that of many technology startups. The then-Princeton computer science student recounted his “Aha!” moment for Forbes magazine: “I assumed there would be a website with all the world’s art on it,” he admitted.15 Cleveland searched for a picture to decorate his dorm room, but an “everything store” for art didn’t yet exist. This struggle exposed a problem to be solved. In this etiology, the art poster was a precursor to the Internet, in its potential to democratize the world’s art. The art poster also carries symbolic currency in the coming-of-age story of art dealer Larry Gagosian, who became an Artsy investor in 2010. It is often repeated that Gagosian got his start in the art business by selling posters on a sidewalk near the campus of the University of California, Los Angeles.16

Cleveland’s father David is a novelist and art historian credited with a recent history of American Tonalism. His mother works in finance. In total, Cleveland’s biography reads like the expression of an algorithm, a perfect set of traits that result in a CEO archetype for a company that synthesizes technology, art, and commerce. Besides Gagosian and the elder Cleveland, the company is advised by Marc Glimcher, president of The Pace Gallery, and the esteemed John Elderfield, Chief Curator Emeritus of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.17

Mechanisms

When Artsy was launched it sought revenues from galleries through a commission model. Ranging between one and six percent of total sales, galleries were trusted to pay Artsy under an honor system for each sale made to a collector who had first encountered work on the Artsy website. A year later this format was abandoned and Artsy transitioned to a subscription-based payment model. Galleries that are accepted to the Artsy platform now pay a monthly subscription fee, which can range from around $400 to $1,400 a month.18 Included in a subscription is a set of marketing and sales features such as a gallery profile page, unlimited artwork listings, and the promotion of exhibitions and art fair participation. Artsy will do “targeted email campaigns to users who ‘Follow’ the gallery’s artists,” and, notably, “Artsy also broadens the potential audience for its gallery partners through Search Engine Optimization (SEO).”19 Unlimited artwork listings and SEO mean that subscribing galleries will have more of their artwork at the top of every search.

This all adds up to a fairly straightforward business model, but it produces incommensurable search results, caught between established art historical criteria and subscription fee levels. These impartial results favor an uneven taxonomy of artworks valorized by select “real world” institutions. And since Artsy only partners with art institutions, an unaffiliated artist can only gain visibility through established channels. As a result, there is little chance to discover an unrecognized, emerging artist.

On its website, Artsy highlights its “Education” section as a set of tools for educators and students.20 For instance, if we follow advice posted for teachers and browse tendencies in contemporary photography, the delivered thumbnails are arranged from top to bottom with the likes of Robert Paul Kothe, Bernhard Handick, and Michael Dweck. It isn’t until six or seven rows down that the survey course staples begin to emerge, with a couple of Sally Manns, three Thomas Ruff typological portraits, and some tasteful Mapplethorpes, before the listings begin to degrade again. A photography survey can be filtered out of this muddle, but not without some effort. The vertical scroll of images is in service to more than one demand: A sale always goes down better with a dash of edifying content.

The centerpiece of Artsy’s taxonomy is the ambitiously titled Art Genome Project. It is a database of contemporary and historical work presented as an array of thumbnail images searchable through a web browser. On the back end, the labor of the Genome Project is carried out by a team of full-time and freelance art historians and artists. They are hired to add assigned terms (an average of twenty-five) for each artist and artwork.

João Enxuto and Erica Love, Artsy Office, New York, NY (8/13/14, 7:03:19 PM), 2014, photograph. Courtesy of the artists.

João Enxuto and Erica Love, Artsy Office, New York, NY (8/13/14, 6:49:55 PM), 2014, photograph. Courtesy of the artists.

João Enxuto and Erica Love, Artsy Office, New York, NY (8/13/14, 6:56:30 PM), 2014, photograph. Courtesy of the artists.

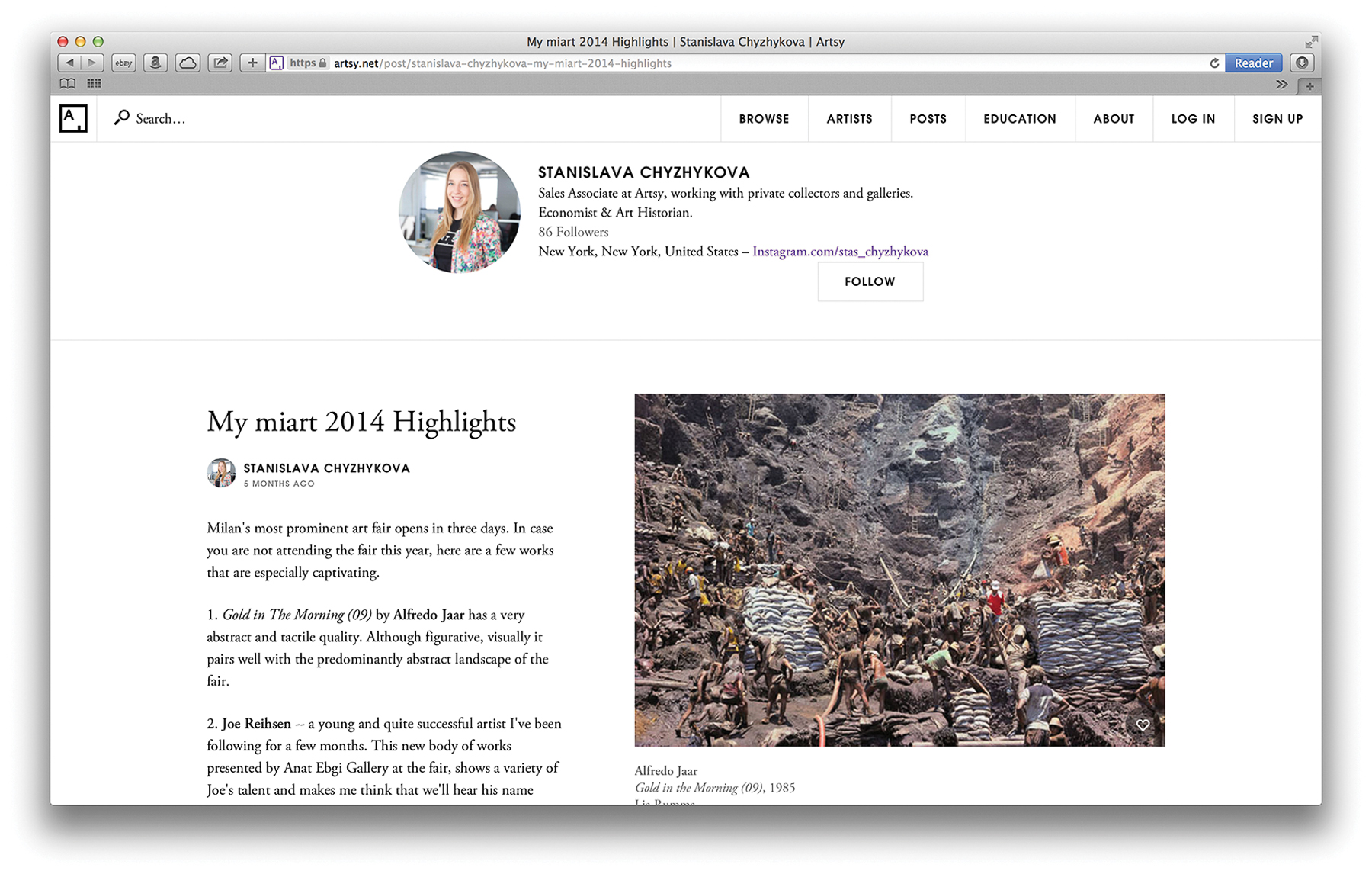

In a rhetorical twist, Artsy mutated genome into the verb genoming. While science has mapped and sequenced the DNA of living organisms, Artsy has inverted this process by overlaying dominant traits on a palimpsest of JPEG files collected from art history. How might artworks be distilled to a set of recognizable traits without being conceived as anything other than essentialized? According to the Artsy website, the Genome provides complexity beyond conventional, non-hierarchical metadata tags. There are over 1,000 genes in fourteen different categories, such as “art-historical movements,” “art mediums,” and “contemporary tendencies.”21 Unlike tagging, these terms are weighted according to relevance on a scale of 1 to 100.22 For example, a picture such as Alfredo Jaar’s Gold in the Morning (1985), which features a rocky landscape with many figures, might be assigned a value of 50 for portrait and 50 for landscape. These numbers saturate each image with metadata. With over 1,000 genes to choose from, how might the sum of the terms “Violence,” “Political,” “Architecture,” “Focus on the Social Margins,” “Installation,” “Art of the 1990s,” “Globalization,” “War and Military,” and “Film/Video” come to represent the work of an artist like Alfredo Jaar? And how is it that “Photography” is conspicuously absent from this lexicon?23 It is a missing gene that might call the entire Genome into question. The Art Genome Project is a process of reinscription that, like all social distinctions, relies on historically constructed traits. In his linguistic study of the origins of the word data, Daniel Rosenberg found that “today, when we speak of data, we make no assumptions at all about veracity. Electronic data, like the data of the early modern period, is given.” Rosenberg proposes, “The data we collect and transmit has no relation to truth and reality whatsoever beyond the reality that data helps us to construct.”24

Courtesy Artsy.net.

Natural Selection

Just as there are districts of artists fighting for daylight in the Hunger Games of art-market validation, there are also legions of underemployed art historians and academics seeking gainful employment. Currently, nine genomers are working at Artsy to attach metadata to art and artists. All have a background in art history and/or library science. Many have advanced degrees. The most recent hires are freelancers who are required to work remotely on three-month contracts, with the potential for renewal. Training consists of a one-and-a-half-day genoming intensive at Artsy Headquarters. If hired, genomers are asked to work a minimum of eight hours a week.25

The Genome is described on the Artsy website as “the product of a dialogue, the process of a very large collaboration, the collecting of information which is already out there, rather than a vocabulary we just ‘invented.’”26 If the Art Genome consists of “what’s already out there” in an art historical canon, then it stands to reason that it can be completed, to be occasionally updated as new data emerges. Once entire art historical periods are cataloged, this form of human labor will be de-valorized. When art historians submit to the wage labor of search engine optimization, they are participating in the process of their own obsolescence. Eventually, with enough data, the entire Genome might become automated through cloud-based computation.

In a similar vein, Jaron Lanier describes how the translation of a passage by Google does not magically emerge out of a cloud but rather is correlated from previous translations across the Internet. Importantly, Lanier points out that “the human translators are anonymous and off the books. The act of cloud-based translation shrinks the economy by pretending the translators who provided the examples don’t exist. With each so-called automatic translation, the humans who were the sources of the data are inched away from the world of compensation and employment.”27 As Internet technologies have dismantled and distributed power, they have also extended power by obscuring it.

Artsy also pays freelance writers for reports that often translate the deterritorialized and fragmented structure of the larger global art market into narrative form. Artsy’s editorial content identifies global art market trends from sites like art fairs and biennials. These dispatches can sometimes carry the incongruity that comes with corralling heterogenous artworks in a single space. One example is a report by Stanislava Chyzhykova, a sales associate at Artsy, on the Miart art fair in Milan. “Gold in the Morning (09) by Alfredo Jaar has a very abstract and tactile quality,” she writes. “Although figurative, visually it pairs well with the predominantly abstract landscape of the fair.”28 Jaar’s photograph of the Serra Pelada mine, which was hand-dug by self-employed Brazilian miners, makes backbreaking labor visible. This is in stark contrast to digital labor, which ventures such as Artsy render invisible. Perhaps this is why Chyzhykova articulates the display of labor power as a formal property, mirroring the unrecognized and unremunerated labor that drives the digital economy.29 In one of many impious asides in Capital, Karl Marx relates the common perception of primitive accumulation as playing approximately the same role in political economics as original sin does in theology. The industrial potentates of Marx’s time were the direct beneficiaries of epoch-making revolutions, leveraging those moments “when great masses of men are suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence, and hurled onto the labour market as free, unprotected and rightless proletarians.”30 This was the case for the feudal serf, and it parallels the upheavals faced by the creative class in this most recent digital “revolution.”

Genetic Drift31

The exponential growth of data and information technologies has shaped our current moment. Like most relational databases, Artsy’s Art Genome provides seemingly infinite possibilities for the reconfiguration of data. A database also conveys a sense of mastery, and as the user navigates it she can imagine herself as central to its view. Yet when searching the Art Genome, the user has only a partial view of art history. “Database and narrative are natural enemies,” asserts Lev Manovich. “Competing for the same territory of human culture, each claims an exclusive right to make meaning out of the world.”32 The parts of history that are by nature messy and contingent cannot be represented in databases. How does this square with Artsy’s stated intent to have the database educate? Matthew Israel, an art historian, became the head of the Art Genome division shortly after earning a PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.33 During a conversation via Skype, he compared the applicability of Artsy’s Genome Project to that of an art history survey course. “You need to give people a road map,” he said. He continued with a version of Art Genome orthodoxy: “It lowers entry barriers by providing greater opportunities to catalyze an art experience.”34 However, the idea that databases are in the service of history is a prevalent misconception. Rather, databases consist of algorithms that produce the most efficiently ordered dataset based on the tagging and weighting of the user’s query. As the writer Mike Pepi explains, “Information stored in a database is not designed to conjure, remind, or look back in retrospect. On the contrary, these data exist to power an application.” Databases are designed for “optimal end-user performance, not, as it were, some higher calling to organize information as an abstract service of historical memory.”35

Heredity

Ultimately, Artsy follows traditional models of the art market by replicating its existing hierarchies, performing the function of an art advisor who connects collectors with galleries. The high valuation and interest in Artsy can lead one to speculate that the value of the site may not lie in its gallery subscriptions. The Art Genome Project is at the core of Artsy’s business and its primary asset. Its algorithm could exist separately from the Artsy platform, justifying the significant resources, both financial and human, that have been allocated to its development. As is often cited, Pandora’s Music Genome was the inspiration and precursor to the Art Genome. Recently, Pandora was hired by Universal Pictures to advertise its upcoming film, Get On Up, the new James Brown biopic. Pandora inverted its Music Genome to locate listeners whose musical tastes shared traits and attributes to James Brown’s music. According to their press release, Pandora “hyper-targeted the listeners with innovative ad banners that dynamically surface insights from the genome in a way that is directly and immediately relevant to the listener. Listen to Bruno Mars and you’ll discover that [sic] the R&B connection between him and James Brown.”36 The campaign allowed Universal to reach a wider audience beyond identified James Brown fans. It is conceivable that the Art Genome could be applied to the next artist movie biopic. If you like Keith Haring, George Condo, and Julian Schnabel, then you will like the next Basquiat film. While the database can reduce an artist to twenty-five genes, a new biopic can reinscribe his narrative.

Co-Evolution

This spring, in addition to the posting for genomers, Artsy announced a job opening on their website for a product designer. Under the heading “Our Design Ethos” it announced: “Design doesn’t stop at screens and pixels. Every part of the customer experience can and should be designed.”37 Nothing is left to chance when total design dictates this encounter with an artwork. Graphic user interfaces (GUIs) are engineered to animate arrays of images for web browsers. Pictures are no longer inert. They are to be touched, pinched, clicked, and zoomed, while algorithms coax eyeballs to lock on a select JPEGS in the screen’s “infinite vertical scroll.” Here we are educated in the attention economy.

Alfredo Jaar, Gold in the Morning, 1985. Lightbox with color transparency, 102 × 153 × 15 inches.© Alfredo Jaar. Courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples, and the artist, New York. Screenshot, Artsy.net, August 8, 2014.

Alfredo Jaar, Gold in the Morning, 1985. Lightbox with color transparency, 102 × 153 × 15 inches. © Alfredo Jaar. Courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples, and the artist, New York.

The infinite scroll is screen design hyperbole. This illusion approaches fact as the number of available search results increase. Artsy has over 180,000 results, which produces an adequate semblance of the infinite. Artsy’s competitors typically contain web pages with a footer: The Paddle8 platform has buttons to unravel additional thumbnails while Artspace frames browsing with paginated results. It was the Contemporary Art Daily art blog that received a sustained analysis of the “infinite” or “running” scroll in the 2013 Artforum article “2011: Art and Transmission” by Michael Sanchez. These observations focused on Contemporary Art Daily as an image aggregator that benefited from the ubiquitous web access provided by the iPhone and iPad. Sanchez states that we are living in an aftermath, where “a set of technical innovations have arisen that have reconfigured conditions for the production and distribution of art.”38 The rest of his essay explores this disruption in the art field.

Contemporary Art Daily was launched in 2008 by Forrest Nash, then a student at the Art Institute of Chicago. He started with a modest following but quickly increased his audience by posting installation views of current worldwide exhibitions in a recognizably austere and cool style perfectly suited to the clean aesthetic of Apple products. According to Sanchez, 2011 was a pivotal year for the iPhone and the iPad, and most critically for the images one could view on these surfaces. A prominent pull quote in Artforum announced, “Art is no longer discovered in biennials and fairs and magazines, but on the phone.” “Contemporary Art Daily,” Sanchez points out, “replaces the discrete pages of the print journal and the gallery with a running scroll.”39

As the influence of Contemporary Art Daily grew, Sanchez suggests that a crop of galleries synchronously emerged to meet the demands of screen platforms. “These galleries all employ a large number of high-wattage fluorescent-light fixtures, as opposed to more traditional spot lighting.” This observation by Sanchez is verifiable by a visit to any contemporary space in Berlin, New York, Los Angeles, London, and other, smaller art worlds. Whether lighting fixture upgrades came as a result of Contemporary Art Daily or, as Sanchez claims, were a response to the white pulsating LCD technology introduced by Apple in 2010, remains up for debate.

The stakes of developing an analytic toolkit for art consumed via the Internet are high for a company like Artsy, which has wagered its future on this form of transmission. It is undeniable that the computer screen, albeit one anchored to a desktop, fosters novel viewing habits. Sanchez has, at the very least, initiated a move toward understanding such tendencies. Might this variety of art criticism become indistinguishable from e-commerce art consulting and ultimately be more valuable than the Art Genome Project itself? Could a Clement Greenberg of the computer screen emerge to demystify the habits and desires of elusive customers?

Extinction

If we return to Contemporary Art Daily and scan its content, it quickly becomes apparent that the blog promotes a limited constellation of galleries. This coterie of institutions, with its considered selection of artists, meets the narrow criteria for an over-reaching theory of the now. Sanchez deconstructs the visual effects of vertical scrolling with the language of pop-neuroscience. Gray paintings serve as “visually therapeutic” forms that counter “the anxiety fed by the speed of the scroll interface, slowing the eye down and dilating the pupils.” This “affective content” is brought into a larger feedback loop of networks, informational feeds, and iPhone interfaces that ultimately shapes the contemporary art world. Contemporary Art Daily becomes a Petri dish where a young art critic might see the ingredients for “a complex dynamic of causes and effects, reciprocal mimicry and recursion, in which traditional models of artistic influence no longer apply.”40 Again, the Internet is deployed as a disruptive force to flatten out some of the old institutional gatekeepers only to replace them with a feedback loop of self-regulation. The cycle of images coming from Contemporary Art Daily become trapped in a recursive space of white walls, cool fluorescent lights, and even cooler pulsating screens dotting the globe. This relatively small, anxious network of micro-trends has gradually hardened under new institutionalized terms.41

To quote the media theorist Benjamin Bratton: “‘[P]latforms’ are not only a technical architecture; they are also an institutional form. They centralize (like states), scaffolding the terms of participation according to rigid but universal protocols, even as they decentralize (like markets).”42 These criteria allow for the categorical reframing of Artsy and Contemporary Art Daily as institutional platforms.

How might these platforms shape the dispositions, practices, and production of artists—their habitus as described by Pierre Bourdieu? Sanchez has argued that conventional sociological positioning by artists has been reshaped by the quantitative acceleration of digital networks. Under these conditions, Sanchez claims that artists have become non-subjects, which leads the author away from social theory and toward a theory of systems. If we break out of this particular feedback loop and revisit the art market, the role of social distinctions and taste are still very much intact, “since taste is the basis of all that one has—people and things—and all that one is for others, whereby one classifies oneself and is classified by others,” Bourdieu wrote in Distinction, his study of taste.43

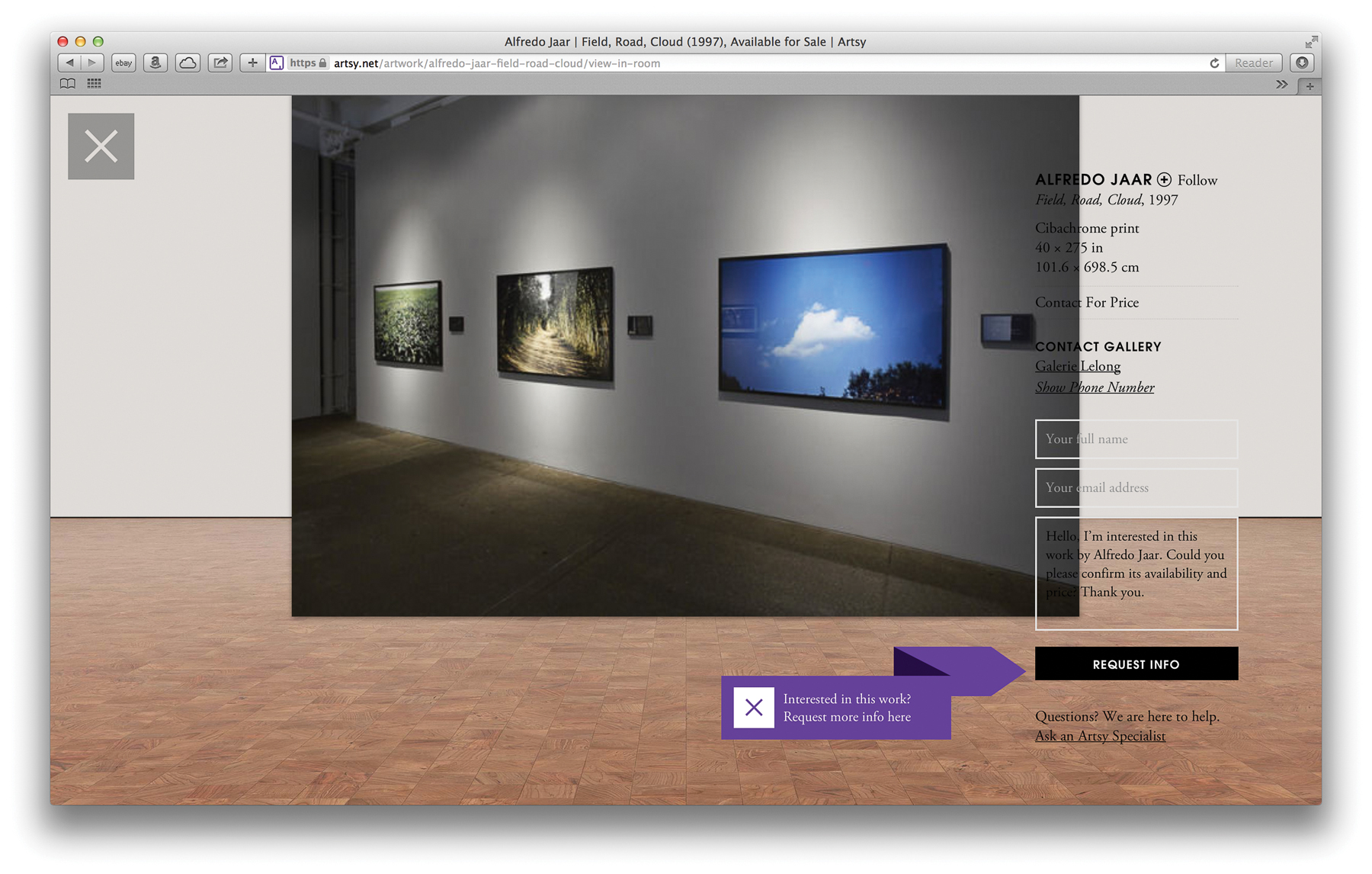

Alfredo Jaar, Field, Road, Cloud, 1997. Three color Cibachrome prints, three B/W Cibachrome prints. Color prints: 40 × 60 inches; black and white prints: 6 × 9 inches; overall: 40 × 275 inches. Edition of 5.© Alfredo Jaar. Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York. Screenshot, Artsy.net, August 22, 2014.

ArtRank (formerly SellYouLater) was introduced in early 2014. It has since become the subject of much controversy as it claims to “graph prime emerging artists based on qualitatively-weighted metrics.” Like a brokerage firm, a collector consults ArtRank to know which emerging artists to buy and sell to minimize their investment risk. ArtRank’s “qualitatively-weighted metrics” shape a standard of taste thereby regulating an unregulated market. The results have led to the homogenizing effects represented by a new class of paintings known as crapstraction, flip art, and zombie formalism, among other designations. It is probably not a coincidence that these paintings also fit the description of the “therapeutic” and “low-contrast” abstract paintings that Sanchez claims are suited for the iPad screen.44 Various critiques of the phenomenon have played out in the art press, with the best known being a piece by Jerry Saltz for Vulture.45

The young art historian Alex Bacon responded to what he perceived as a one-sided debate with a prompt: “Critics, whether they like or dislike the work formally, should be fighting back against this hijacking of art, by at least taking the terms of the work seriously.” Bacon calls for a new criterion. “Today a ‘collector’ wants to own the same things his ten friends do. It’s a status symbol, a register of a certain kind of taste…a certain level of economic achievement, and corresponding entry into an ‘in crowd’ who all have the same art portfolio.”46 These concerns were central to Bourdieu’s sociology of art and to his acolytes, which included a wave of institutional critique artists in the 1980s and 1990s.

João Enxuto and Erica Love, Artsy Office, New York, NY (8/13/14, 6:54:27 PM), 2014, photograph. Courtesy of the artists.

In a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, Carter Cleveland predicted that the art market would massively expand in the future. He wrote, “If art becomes a ubiquitous part of culture, collecting could become normal behavior for households with disposable income, just like buying luxury fashion and jewelry.”47 This presents a paradox, where the symbolic value of art (as an expression of individual and/or class taste) would collapse when everyone participates in the “democracy” of art collecting. Cleveland continued, “At Artsy we are seeing this phenomenon firsthand among new collectors in Silicon Valley, a market we have early visibility into given our tech startup roots.” From this statement it becomes clear where the “disposable income” will emerge in a nation with $11.65 trillion in total household debt.48 The promise of the Art Genome Project is to connect more people to art more efficiently. The bottleneck that stood between Cleveland and his ability to buy fine art from his Princeton dorm room was not a supply and demand problem to be solved by the Long Tail business model perfected by Amazon.49 Fine art is unlike books, music, or really any other commodity. To provide art for everyone may actually require changing the world.

João Enxuto and Erica Love have been collaborating since 2009 on work that examines the effects of new technology on aesthetic categories, institutions, and labor. They live in New York City.