When the artist Gary Beydler passed away last year, he left behind a body of work long since completed. Beydler stopped making art in 1977, after the debut of his last and most ambitious work. Venice Pier, an eighteen minute film, was exhibited to a reportedly distracted, peripatetic, and indifferent Los Angeles audience at Gagosian Gallery. Bitterly disappointed, Beydler dropped out of the art world, got a real job, raised a family, and his work entered a long period of critical near-oblivion.

Like so many artists, Beydler began as a painter and moved into sculpture. His materials were consistently humble: string, clay, pencil marks, prefabricated metal shapes, consumer-grade snapshots, and so on. But while his paintings and sculptures were well regarded in their moment, his films remain his main achievement. There aren’t many of them–just six, in fact, all produced within a two-year period.

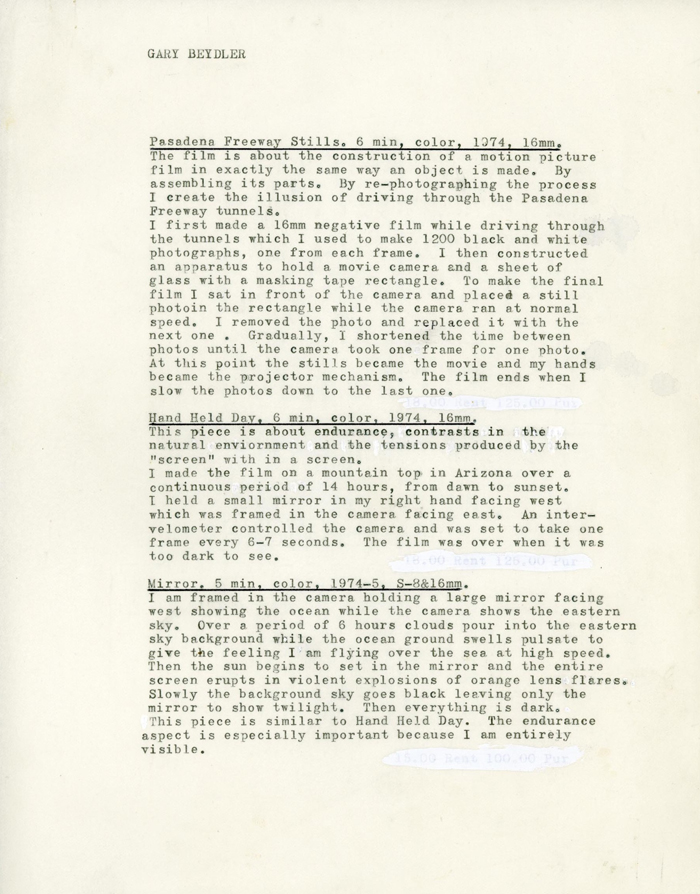

Gary Beydler, 1979, photographer unknown. Image courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

I first learned of Beydler in a college experimental film class. The film I saw was Hand Held Day (1974). It’s probably his most famous, though perhaps not his best. (It’s also the only one that has found its way onto YouTube, bizarrely scored by someone other than the artist with a hideous folk-metal soundtrack.) It is best introduced by one of Beydler’s own descriptions, a classic bit of no-nonsense, process-driven, tough-guy conceptualism:

I turned the camera on around 6:30 a.m. It was on a tripod. In the middle of its view, I placed a mirror cemented to a small steel rod attached to a wood stand. The rod was behind my arm. My elbow rested on top of the wood stand. The intervalometer was set to take one frame every six to seven seconds. Fewer than three reels of film were needed during the fourteen hours. I was not able to leave or stop the camera. I drank and ate a minimum. I had to be careful not to move my hand or arm at all.1

The Desert

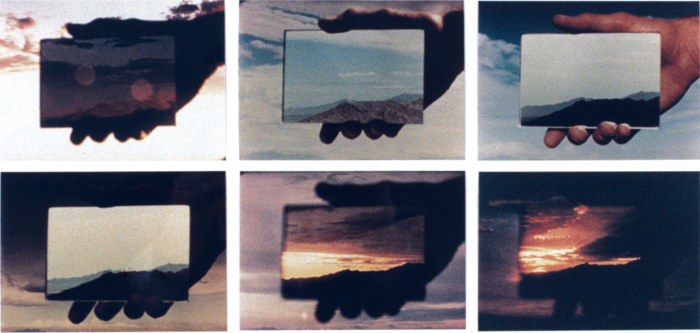

Hand Held Day was shot in Arizona, and the sweep of the desert horizon, punctuated by distant mountains, locates the image in a specifically Western poetics of open space. But almost by design, Beydler’s description of Hand Held Day leaves out the key visual effect that structures the film. At the start, the sun rises in the background in the space surrounding the mirror, while the vista reflected in the mirror remains dark. Over the course of the day, the brightness of the two spaces reaches equilibrium. At sunset, the relationship reverses, and the surround goes dark as the setting sun continues to illuminate the mirror, until the light fades entirely. Just as the sun sets, light flares brightly within the lens, filling the frame with a dazzling red, and then everything fades to black. The nervous, stop-motion jittering of the artist’s hand, with all its minor shifts of position, creates an anxious, vaguely neurasthenic counterpoint to the wash of clouds that roll smoothly across the sky in accelerated time. While the colors of Hand Held Day are acidly romantic, the film has a certain magnificent blankness that recalls Eastern philosophy.

Gary Beydler, Hand Held Day, 1975. Grid of six 4 x 6 in. color prints mounted on mat board; approx. 18 x 24 in. Image courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

Beydler’s film puns on an earlier avant-garde’s adoption of a roving, subjective camera eye, synchronized in thought with the hand that supports it. In place of that construction, Beydler instead stages a theatrical confrontation between hand and tripod. But in Hand Held Day, the dynamism, instability, and shifting gaze of the handheld camera become literalized in the image of the hand itself, while the associated motion is critically attenuated to the level of a subtle twitch, almost a nervous tic. The human element thus commands the frame, declaring a poetic symmetry between dawn and dusk, but when the film is played back, the dominant visual subject becomes the minute, unnaturally jerky wobbling of the hand, which willpower alone cannot suppress. Beydler’s subject is thus neither the empyreal nor the earthly, but a relationship between the two, one framed in the most literal way by the hand of the artist.

The terseness of Beydler’s prose description of the piece and the austere, endurance-oriented aspect of the process it describes recall the better-known performance documents that Chris Burden produced during the same period Beydler was active. Burden was in fact Beydler’s good friend; the two studied together at the University of California, Irvine, in the early seventies in a program famous for the tutelage of the artist Robert Irwin. John Lamb, a friend of Beydler’s from later in life, recalls that Beydler’s exit from the art world coincided with an incident in which Burden asked him to participate in one of his performances and Beydler refused. The tale is almost certainly apocryphal, but it traces the faint outline of an essential difference in approach. For Burden and most of the Conceptualists, the experience of the performance was the art, and the photograph was simply a record. For Beydler, the experience of the artist necessarily remained his alone, and the photograph was the art. Beydler thus remained deeply committed to the pictorial. His interest in color was unabashed, and almost embarrassingly romantic for a generation otherwise committed to black-and-white snapshots and typewriter-font documents.

Gary Beydler, 20 Minutes in April, 1976. Grid of sixteen 4-by-6-inch color prints mounted on mat board, 24 x 30 in. Image courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

The mirror motif recurs in the film Mirror (1974-75), in which the artist is seen standing, holding a large mirror that reflects an image of the ocean. As in Hand Held Day, the time span of a day is compressed into a few minutes. Mirror, however, introduces the person of the artist more visibly. Wearing a pair of dark sunglasses, the artist seems to contain somehow the oceanscape in the mirror, or to be flying above it. The set-up is almost absurdly simple, yet the result is strangely breathtaking. Beydler also produced a large body of photographs on this basic theme of the doubled skyscape, with the mirrored frame-within-the-frame. Printed as 4-by-6-inch color snapshots mounted in rows and columns on sheets of mat board, he produced over a dozen variations on this scheme, with titles such as 20 Minutes in April (1976). While postcard-perfect in their formal charms, these print pieces lack the rigorous shaping of time that Beydler uses so adroitly to command attention in his films.

Gary Beydler, 30 Minutes in July, 1976. Grid of sixteen 4 x 6 in. Color prints mounted on mat board; 25 x 31 in. Image courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

As a device, the mirror beckons a panoply of critical formulations. A mirror can be seen as the symbol of vanity (the Narcissus myth), the site of the ego’s formation (Jacques Lacan’s mirror stage), or the mind of the perfect man (Chuang Tzu), to name just a few famous metaphors. But none of these feels particularly pertinent to the experience of Beydler’s mirror pieces, in which the mirror is never used to show the physical means of production (the camera itself) or the audience (which would require an actual mirror in the screening space). Instead, Beydler’s mirror is a structuring device used to create a double picture, a picture within the picture. The internal picture in the mirror acts as a counterbalance to the otherwise powerful illusionism of cinema, reminding us palpably that we are being shown a place that we cannot fully enter into. This internal space is chronologically synchronous with the larger frame, but spatially set apart from it.

The City

The synchronicity principle of the mirror films, however, is ruptured in Pasadena Freeway Stills (1974), arguably Beydler’s masterpiece. Its initial point of departure is a test not of the artist’s endurance, but rather of the audience’s. In the film, the artist walks into view, sits down, lifts up a photographic print, and holds it in place for the viewer to see by pressing it against what we realize is a pane of glass. The edges of the glass are not visible, because it fills the camera frame. This small revelation, of the presence of the otherwise invisible pane, puts the idea of a photograph’s transparency with respect to its subject subtly in play. The black-and-white photographic print shows a view that appears to be taken through a car windshield on the stretch of the 110 freeway between the Figueroa tunnels, just north of downtown Los Angeles. The artist then takes the image down. There is an obvious cut, and then the action is repeated. Beydler puts up another print, indistinguishable from the first, and holds it in the exact same position, pressed against the glass. Is it a provocation? How many times will he show us the same image?

The process repeats, and slowly begins to accelerate, aided by editing. Subtle, evolving differences in the photographs become apparent, and their progression becomes clear. We are watching a motion picture film being shown frame by frame, with each frame a photographic print handled personally by the artist. The process isn’t rushed, and though the “frame rate” of the freeway images accelerates steadily, there is a generous limbo period in which the motion of the artist’s hands is recognizable, though somewhat jerky, and the freeway image is changing, but at a plodding pace. You know where it’s going, though, and the striptease-like quality of the film’s timing, drawing the viewer along without rushing the business, makes this one of the most deliciously enjoyable moments in art film of the era. At its climax, the freeway pictures speed by at twenty-four images per second, the standard projection speed of a motion picture projector, and the cinematic illusion of movement along the freeway is utterly conventional in the frame-within-the-frame. All around the black-and-white image, however, the artist’s hands flicker in unnatural, stop-motion time. After a minute, the process begins to reverse. We keep traveling forward on the freeway, but the individual prints receive longer and longer screen time, until we are returned to the conventional chronological space of the artist in the chair, handling his snapshotsized prints in real time.

Gary Beydler, Pasadena Freeway Stills, 1975. Four 4 x 6 in. Color prints on mat board, 24 x 18 in. Image courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

Pasadena Freeway Stills is ingeniously lapidary. The symmetry of its plan is total. Yet of all of Beydler’s films, it traffics the most explicitly in paradox. For the viewer is forced to choose, it seems, between the temporal register of the artist’s hands and the temporal register of the freeway image. As Beydler sets it out, these two realms are entirely interdependent, but mutually exclusive. The great irony, of course, is that this dialectic between illusion and materiality is enunciated within a film that is necessarily entirely illusionistic. The brilliance of the film ultimately lies in the way that it lays bare a set of presumptive distinctions simultaneously, within a single process. As in Hand Held Day, the hands represent artistic agency, presence, craft, and purposiveness. The setting is indoor, presumably that of a studio. The freeway image is, by way of contrast, a seemingly banal, mechanically produced illusion. It could pass for home movie footage. The freeway scenes shot in bright sunlight are contrasted by the darkened space of the tunnels, emphasizing the zooming motion of the speeding camera and animating the entire frame of the individually printed stills. The freeway scene explicitly channels the experience of horizontality and the mise-en-scene of the windshield that nearly every commentator on Los Angeles has reflected upon. And there is another, more nuanced aspect to the choice of site. Geographically, the Figueroa tunnels connect the gulch where the Arroyo Seco and the Los Angeles River converge (the ancient site of the first Gabrielino Indian settlements) with the downtown area developed in the nineteenth century. By positioning his freeway film (the film within the film) in the intermediate zone between these two city-spaces, which are still quite different today, Beydler subtly plays up the overall sense of shuttling between two unlike zones.

In a contemporaneous review of Pasadena Freeway Stills, Beydler is quoted as saying, “I wanted to be a human projector.”2 Like John Henry racing against the steam hammer, Beydler courts failure, and it is only through splicing in the editing room that the film is able to deliver its secondary illusion at a naturalistic pace. Pasadena Freeway Stills can be considered a kind of handmade readymade, by which I mean an art object associated with industrialized fabrication techniques, but created using ordinary, ready-to-hand production methods and/or conventional art materials. The strategy is a fairly common one today, and indeed the readymade concept has become so widespread as to be almost invisible.3 But from a historical point of view, what is distinctive about Beydler’s film is the way that he ironically purports to shift the poesis of production from the camera to the projector.

Beydler was not alone in this trajectory. Also working in Los Angeles in the early seventies, David Wilson, Pat O’Neill, and Morgan Fisher each explored the possibilities of a self conscious, rule-based filmmaking that shifted the metaphoric structure of film away from the camera towards the editing table, the copy stand, and the projector. Fisher especially, whose Projection Instructions (1976) consists entirely of projected text directing the projectionist’s live operation of the device in the projection booth, has expressed admiration for Beydler’s films.

P. Adams Sitney, the doyen of American avant-garde film theory, famously coined the term “structural film” in the late sixties to describe certain self-reflexive film practices of the time:

The structural film insists on its shape, and what content it has is minimal and subsidiary to the outline. Four characteristics of the structural film are its fixed camera position (fixed frame from the viewer’s perspective), the flicker effect, loop printing, and rephotography off the screen. Very seldom will one find all four characteristics in a single film, and there are structural films which modify these usual elements.4

In his later publications, the concept of duration is also added to the “structural” mix: “[the structural filmmakers] elongate their films so that time will enter as an aggressive participant in the viewing experience.”5 As in the early criticism of Michael Fried, the key concept is that of shape, though in film this shape is more often temporal than spatial. In Sitney’s foundational formulation, the structural film evolved as a historical reactions to what he calls the “lyrical” film, as epitomized by the work of the artist Stan Brakhage, in which the camera is offered as a metaphor for eyesight. In the lyrical film, “We see what the film-maker sees; the reactions of the camera and the montage reveal his responses to his vision.”6

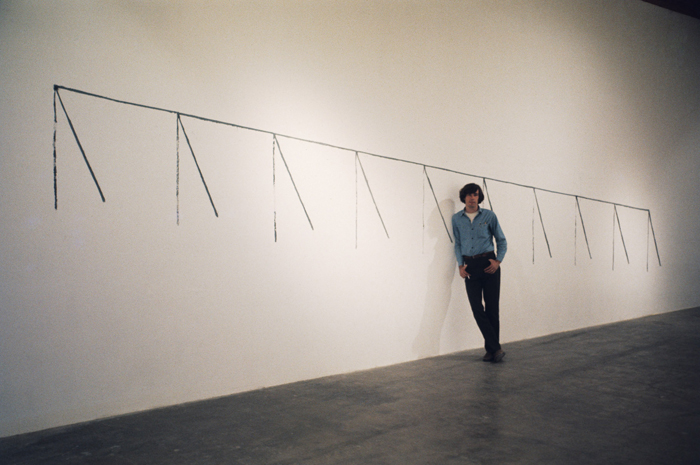

Artist’s statement by Gary Beydler, c. 1977. Image courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

Beydler’s sensibility can be described loosely as So Cal structural. His films use three of Sitney’s four techniques, and he operates with self-reflexive rigor that is “structural” in its essential pedigree. But this identification requires substantial qualification. For one thing, Beydler’s approach to duration is radically different from that of the New York filmmakers. Instead of elongated forms that draw scrutiny towards one’s attention span by testing it, Beydler’s films embrace radical concision. Instead of elongation, we confront compression. Indeed, the classic “structural” film can seem bloated by comparison. The corny murder scene and tedious noodling with color filters in Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), probably the most famous structural film, seem positively diffuse in the company of a Beydler film.

Gary Beydler, Stills from Venice Pier, 1976. 16 mm film, color and sound, 16 min. Images courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

More importantly, Beydler cannot be fully contained by the “structural” appellation because of the various subtle ways in which his films traffic on the boundary between the structural and the lyrical. Hand Held Day can be thought of as critiquing the trademark handheld camerawork technique of Brakhage, but it also paradoxically embodies it in a strange, distended fashion, where the distinction between first person and third person is held in abeyance. In Mirror, the mirror the artist holds aloft allows us to quite literally “see what the film-maker sees,” as Sitney put it of the lyrical film, but we are denied full access to the artist’s psyche by the dark sunglasses, which are never removed. Mirror thus literalizes the core metaphor of the “lyrical” film concept, while simultaneously rupturing its essential premise in a deeply ambiguous fashion. Above all, Beydler is not fully a structural filmmaker because the films, for all of their radical attention to their own “shape,” are not apperceptive. They exist for both the mind and the eye. Beydler’s investment in color and landscape, in particular, is part and parcel of a Romantic lyrical tradition that prizes the renewal of perception. Beydler’s films should thus be seen as, among other things, the endgame of the “structural” conception, an endgame that dissolved that notion’s foundational distinctions and imperatives. And so it is always with a certain discomfort that Beydler’s films are accommodated, in what little criticism exists, into the Modernist cult of the “essential properties” of a medium. Anyone who looks to Beydler to reveal the essence of cinema will be ultimately disappointed, unless we take the very idea of such a thing to be an unresolvable conundrum whose circular qualities can be shown but not said. These are not paralytic, zero-degree works, but high-temperature riddles.

Gary Beydler, 1971. Artwork title unknown; cloth, latex, clay slip; dimensions variable. Courtesy and © Gary Beydler.

The Ocean

Beydler’s last film, Venice Pier (1976), is by far his longest, and his only sound film. Until last year, it was considered lost.7 The film was shot over the period of a year, at various times of day, using fixed camera positions up and down the length of the pier. The footage is edited not according to a temporal logic but to a spatial one. Each cut in the final edit moves the camera further down the length of the pier, towards its terminus. But the result is a jumbled chronology whose lighting and atmosphere skip around irregularly from one time of day to another. The sound track is straightforward and realistic, of waves breaking, children playing, and fishermen going about their business. It’s quite ordinary in a way, and yet the film purveys a charged atmosphere of heightened perception, bringing the language of Light and Space art into film in a way that has often been attempted but seldom been effectively realized.

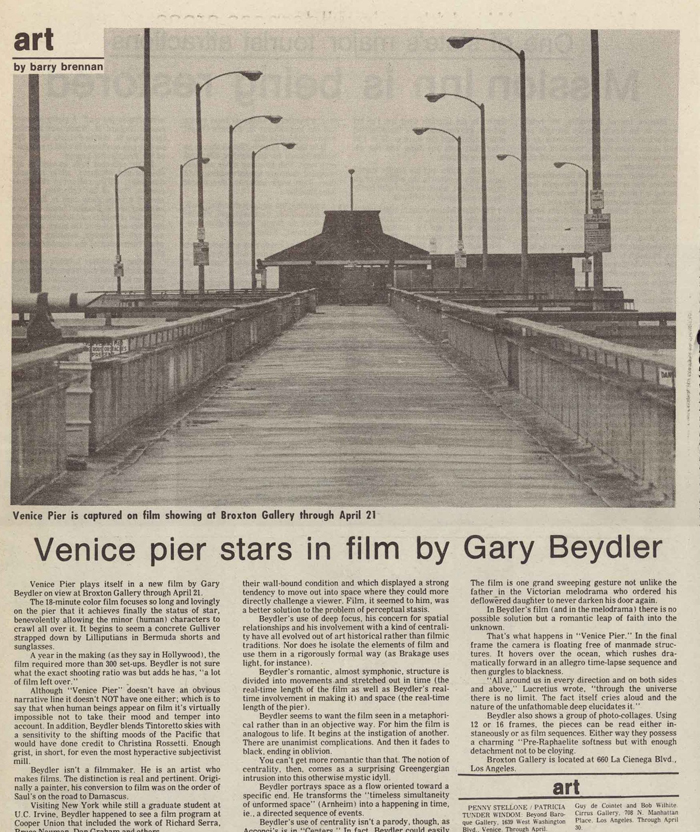

Barry Brennan, “Venice pier stars in film by Gary Bedler,” Santa Monica Evening Outlook, April 2, 1977. Image courtesy of the Gary Beydler family.

Venice Pier is, above all, a bravura exploration of color. While the pier itself presumably stays the same, the atmospheric and lighting conditions on the coast modulate the apparent colors of each scene drastically. Indeed, the film charts virtually every permutation of hue, saturation, and brightness, amazingly without ever breaking with photographic realism. While digging through the Beydler family archives during my research for this essay, I came across an intriguing 35 mm slide, labeled “Venice Pier 1976, Color Film 18 min, Sound Diary of making the film over 1 year, Two versions with color bars that correspond to dominant colors of scenes.” The slide shows two large and complicated drawing plans for the sequence of the shots in Venice Pier, using a vertical strip of color swatches to represent the dominant color of each particular shot. The lengthy rows of text in the drawing are unfortunately illegible in the grainy old slide, and the drawing is photographed at a skewed angle that makes its logic essentially irretrievable. Obvious questions abound: Why are there two versions? How are the two versions different? Why the circular bulge in the sequence at the top of both charts? The original drawings are lost somewhere in the family attic, and I hope some future researcher will be able to locate them and shed some light on Beydler’s compositional process.

But it might not matter much. The important point is that color, for Beydler, was both observational and deeply rooted in the natural world. The colors of the coastal scenes in Venice Pier are wildly varied, but Beydler did not employ color correction (‘color timing’ in the industry parlance) of any kind, preferring to see his footage printed exactly as it was shot. One can debate the theoretical and practical merits of this position, but it remains, at least, a straightforward one. Unlike so many of the Conceptual artists of the era (John Baldessari comes to mind), Beydler did not mock color as being essentially arbitrary or random. Venice Pier grapples profoundly with the full complexity of color, partly by acknowledging that color is both perceptually contingent and inherent in things, both functionally stable and dependent on lighting conditions. In comparison with the deliberately parsimonious approach to color that dominated so much Conceptual art of the seventies, the complexity, virtuosity, and integrity of Venice Pier today seem vastly more accomplished. In the final shot of Venice Pier, the camera passes beyond the end of the pier, and rushes forward above ocean water; the passing waves below are illuminated by a glimmering, ecstatic sunset. Amazingly, this brief but glorious coda is the only moving-camera shot in Beydler’s entire corpus. If you ever get to see Venice Pier, you will perhaps understand why this single shot compelled the art critic of my childhood hometown newspaper, the Santa Monica Evening Outlook, to quote Lucretius, in a wide-eyed review that would never be published today.8 This is nature poetry of the highest order. As in all of Beydler’s work, the mechanism is simple (a boat!) but after the intricately structured interplay of all that has preceded, the effect is one of almost miraculous release. It was, and remains, a grand exit.

Benjamin Lord is an artist based in Los Angeles.

The author would like to thank the Beydler family for their generous cooperation and for permission to reproduce the associated images.