Hans Haacke 1967, Installation View at The MIT List Visual Arts Center, October 21–December 31, 2011. Photo Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center.

When Clement Greenberg declared in 1960, “[M]odernist art belongs to the same specific cultural tendency as modern science,” he was speaking of a very specific and historical mode of science–one engaged, like painting, in fundamental self-critical inquiry.1 Greenberg was making the case for an already existent language of experimentation, research, and problem solving used by artists, though it was a self-criticality carried out in the arts in “a spontaneous and largely subliminal way.”2 The convergence of art and science would become far more intentional as the 1960s wore on. Yet the “cultural tendency”–the search for specific and autonomous truths–to which both art and science belonged was itself rapidly changing during that period. An art criticism that resembled theoretical science was, in 1960, already nostalgic. Compare, for instance, Greenberg’s basic scientist to the “organization scientist” presented by William H. Whyte in his 1956 best seller, The Organization Man.

Whyte relegated the “rugged individualism” of the theoretical researcher to American mythology, noting that, since midcentury, these figures had been replaced by a social ethos based on group effort, interdisciplinary research, and an emphasis on applied rather than fundamental science.3 The increasing scale of the new “organizational society,” to which this scientist belonged, was reflected in corporate structures but also arose spontaneously in the form of regional and professional organizations that could affect specific political and social changes where large political parties that had to appeal to a broader base could not. While less heroic than his predecessor, the “Organization Man” gained the power of collectivity, to negotiate effectively in the case of unions and professional organizations, and to problem-solve in the case of corporations and laboratories. Samuel P. Hays noted that the rise of the organizational society was especially apparent in the increasingly stratified and vertical structure of higher education, which became the primary way of conferring expert status in a variety of disciplines, the arts included. In postwar America, the organizational model of scientific research affected academia as much as the corporation, particularly in the top five research universities that took on government contracts.4

One wonders what Whyte and Hays might have made of the recent series of exhibitions held at the List Center for Visual Art that commemorate the artistic heritage of one of those top five institutions, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Coinciding with the university’s 150th anniversary celebrations, Otto Piene’s Lichtballett, Hans Haacke 1967, and Stan VanDerBeek: The Culture Intercom, which was co-organized with and recently installed at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston, examine MIT’s historical commitment to aesthetic innovation. They also highlight the unique cultural impact of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS), founded at MIT in 1967.5 VanDerBeek was a center fellow. Piene was both a fellow and the long-time director, while Haacke was linked to CAVS through Piene and Jack Burnham. There has been a renewed interest over the past decade in historicizing the art-and-technology collaborations of the late 1960s, with concepts such as “systems,” “information,” and “inter-media” at the fore of those discussions. The restaging of these early technological works will certainly contribute to the debate by offering insight into the phenomenal and affective experience of display that was central to an understanding of the productive possibilities of technology in the 1960s. However, art world observers may be most struck by the opportunity these exhibitions provide us to revisit a moment when the process of postgraduate professionalization for young artists had not yet hardened into its current form.

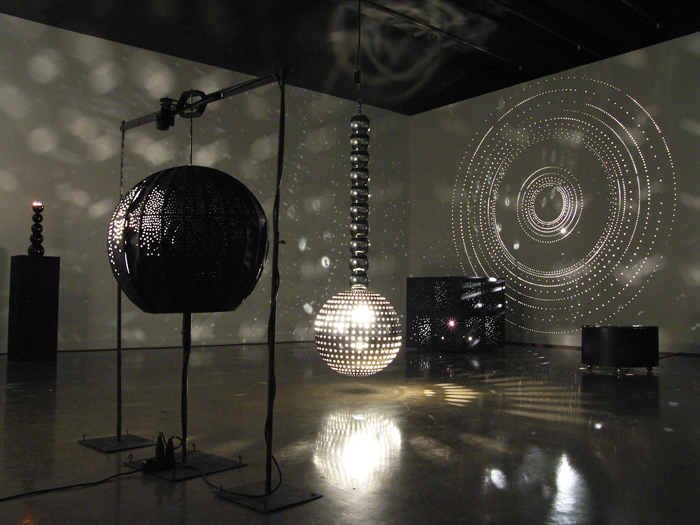

Otto Piene: Lichtballett, installation view at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, October 21–December 31, 2011. Photo: Gunter Thorn. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center.

Otto Piene: Lichtballett, installation view at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, October 21–December 31, 2011. Photo: Gunter Thorn. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center.

CAVS was ultimately the vision of one man, founder Gyorgy Kepes. The Hungarian painter and photographer joined Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s studio in 1930, emigrating with him first to London in 1935, and then to the United States in 1937. Kepes taught courses at the New Bauhaus in Chicago (which became the Chicago School of Design, then the Institute of Design, then merged with the Illinois Institute of Technology) from 1937 to 1945 before accepting a teaching position at MIT. The unique brand of modernism emerging in Boston in the 1950s and 1960s, which was optimistic and humanist, as well as the city’s distance from New York, contributed to the research culture of CAVS. In particular, the center was shaped by an explicit linkage between vision and scientific progress, as well as by notions of unity and wholeness that the visual field represented. Kepes and older art writers such as Rudolf Arnheim and Herbert Read feared that Man’s capacity to control nature had outstripped his ability to perceive it, and therefore his ability to allocate his power wisely and with sufficient empathy. The artists of CAVS were thus charged with a very specific project: to create, through systematic and empirical perceptual research, a more legible urban environment and a more perceptually sophisticated citizen for that environment. So aligned were Kepes’s notions of art research and the research university that in his 1967 proposal for the center, Kepes boldly claimed that, “Making a place for the visual arts in a scientific university is imperative for a reunification of Man’s outlook on life.”6

The first fellows–mostly acquaintances of Kepes–were given a studio space and a small two-year stipend as well as access to the expertise available on the MIT campus and the larger Cambridge community. Unlike the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program, in New York, which was founded one year after CAVS as part of the educational outreach program of an urban museum, CAVS favored a narrow set of interests among its participants and did not provide a schedule of visitors or ersatz instruction, since it was understood more as a brain trust than a classroom. In its structure, it was perhaps most reminiscent of the collaborative research teams popular in corporate and scientific settings; tangible outcomes were expected as well as a collectivist mindset.

Had he visited CAVS in its heyday, Whyte would no doubt have recognized the artist he found there, though Greenberg might not have. Like Whyte, Kepes was concerned with the increasing “scale” of culture. The official focus of the center was on interdisciplinary art production and large-scale interventions into culture, especially in the urban landscape, using technology and science as its primary allies. Kepes sought to coordinate and direct artists as particular kinds of specialists together with corresponding specialists in other fields, in order to set and implement tangible goals within the public sphere. CAVS was to the Greenbergian model of self-critical inquiry what the “applied science” of corporate research teams had been to the theoretical scientist of yore. Whether romantically utopian or brazenly instrumental in its goals, it was an interested science.

And while Kepes was interested in reclaiming urban space in the name of an ordered vision of wholeness, MIT had a vested interest in promoting the arts. The sciences were involved in an urgent struggle to self- differentiate and especially to distance science at large from the brand of science that had produced the atomic bomb. This was a particular problem at the university level, where a presumed humanist outlook broached questions of scholarly ethics and their compatibility with war research. In 1968 alone, MIT received $108 million from the Pentagon in order to fund both on-campus research in computer technology and classified off-campus projects in surveillance and missile-guidance systems. Urged by student and faculty protest in the late 1960s, the university was under pressure to divert more resources into solving domestic and social issues.7 The Center was one aspect of this rebranding that simultaneously helped to justify the place of the humanities at MIT. In the era of C.P. Snow’s “two cultures,” scientific approaches could lend rigor to the humanities, just as art could supposedly temper and humanize the sciences.

The internal dynamic of the center was almost entirely a response to Kepes’s own strong sense of the social purpose of art. His writings on design, especially his 1944 manual Language of Vision, had been influential at all levels of art education in the United States. Rooted in Gestalt psychology, Language of Vision insisted on the primacy of vision as a source of knowledge and the means of communication within a healthy society. According to Gestalt theory, perception could be studied, understood and taught, so Kepes conceived of an alliance between artist and designer under the banner of scientific research, with the goal of honing our collective visual instrument. Hence, the “visual studies” in the center’s title, as opposed to the tradition of the “fine arts” it presumably left behind.

The role of the artist-researcher, Kepes felt, was to “sustain Man with visions of felt order.” Order, a key term for Kepes, was midwife to a new analogy-making consciousness. Kepes had compared Modern art and scientific photography in his 1956 exhibition New Landscape of Art & Science, which in addition to celebrating the possibilities of new technology, insisted on the analogous forms of the natural and manmade worlds. When Kepes referred to the productive possibilities of technology, however, he was primarily speaking of analog technology–spectroscopy, x-rays, holography and so forth–not the burgeoning world of computer science that fascinated many of the CAVS fellows. Like photography, Kepes presented new media, such as radio, television and film, as potential transmitters of naturalized organizational patterns. This difference would mean not only different tools of choice for Kepes and his fellows, but also the difference between thinking in terms of unified organic systems and thinking in terms of variable, networked relationships.

Visual Studies was, for Kepes, both a discipline and disciplinary. “To perceive a visual image,” he wrote, “implies the beholder’s participation in a process oforganization…. [H]ere is a basic discipline of forming, that is thinking in terms of structure, a discipline of utmost importance in the chaos of our formless world. Plastic arts, the optimum forms of the language of vision, are therefore an invaluable educational medium.”8 The educational mission of the arts was to take on the new “civic scale” of culture, which implied the special capacity of the arts to form not only cohesive subjects but also a cohesive citizenry. In the 1950s, Kepes had directed the photographic studies that would form the core of Kevin Lynch’s seminal book on urban planning, Image of the City (1970), which addressed the ways that individuals navigate and understand the geography of American cities. That project, and Kepes’s belief that the contemporary world was one of visual chaos, helped to guide the most concrete mission of the center: the creation of public art that would provide moments of contemplation within the otherwise unstructured experience of urban space.9 By 1960, Kepes had extended his critique of visual literacy from two-dimensional design to the whole spatial environment, claiming that mankind had become “trapped by a crisis of scale.” With this shift, Kepes anticipated the transformation noted by Hays in 1977–a need by growing technical systems not only to understand but also to control the increasing number of variables upon which business and public enterprises depended, until they began to address the necessity of changing the “total environment.”10

In the spirit of illuminating the underlying structures of experience, Kepes dedicated the inaugural years of the program to artists working with light and movement, particularly artists who aspired to a “civic scale” for their work. Otto Piene and the critic Jack Burnham made sculptures of light; VanDerBeek and Ted Kraynik worked in the new media of video and electronics; Wen-Ying Tsai, Vassilakis Takis, and Harold Tovish made kinetic sculpture. The center proposal emphasized the fellows’ “alertness to certain common tasks” and the necessity of interaction between artists and specialists in other fields in order to reshape the environment. Except for an unexecuted proposal for an enormous light tower in Boston Harbor, however, the first two years of the program produced mostly solo exhibitions at MIT’s Hayden Gallery and at Howard Wise in New York.11 Nevertheless, the first fellows shared a concern for the wondrous effects of simple technologies. Tsai presented his Cybernetic Sculptures–kinetic works that exploited the phenomenon of apparent motion, and Takis showed his Magnetic Sculpture, which put the invisible electromagnetic field to quietly magical effect. At MIT, Jack Burnham explored the theoretical consequences of Haacke’s wind and water sculptures, systemic works that engaged slow natural phenomenon such as freezing and photosynthesis as their materials, and Piene continued his electronic light ballets and inflatable sky sculptures. The surprisingly cohesive sensibility–the darkened exhibition spaces they required, the bland and vaguely mechanical materials, the subtle transformations and slowed gazes they invoked–seemed suited to a group exhibition.

When Kepes was selected to direct the American pavilion at the 1969 Sao Paulo Bienale, he planned to create a bipartite exhibition with one half devoted to “information” in the form of a multimedia presentation about art in the United States, and the other devoted to “community,” a collective, interactive presentation by artists. Individual contributions were to remain unlabeled and the whole displayed in a darkened room where the viewer could alternate between biomorphic works of “living light” and works employing sensory deprivation such as anacoustic and monochrome spaces. According to Kepes’s understanding of perceptual organization, such a space could produce a seemingly authorless experience akin to nature while also offering a highly structured visual education.

The show became untenable when nine of the participants (among them Robert Smithson, Jack Burnham, and Hans Haacke) withdrew in protest against the military regime in Brazil–the same regime that Kynaston McShine would criticize in the Information catalog the next year. Kepes’s stealthy version of social activism was at odds with the next generation’s more antagonistic culture of protest. The show generated letters of refusal from CAVS fellows, and Lucy Lippard and Robert Smithson, who suggested that the problem lay not only with the venue but with a curatorial vision uncritical of technology and enamored of collaboration. In a frequently cited letter to Kepes, Smithson wrote, “The team spirit’ of the exhibition could be seen as endorsement of NASA Operations Control Room with all its crew-cut teamwork…. If one wants teamwork he should join the army. A panel called ‘What’s Wrong with Technological Art?’ might help.”12

The fissures between Kepes and his fellow artists continued to appear in the show’s second incarnation in D.C., Explorations (1970), which included almost all of the center fellows as well as artists of a similar stripe, though significantly not Smithson. For those who had entered the program in 1967 and 1968, the show was the culmination of individual projects developed at the center, and reflected the biomorphic qualities of much of their work. Kepes described the exhibition concept as a “little forest” or “ecological garden” of morphologically analogous displays of natural and perceptual phenomena. The tone of the exhibit was lighthearted and was billed as “a celebration of light, heat, cold, air, electricity, magnetism–forces so omnipresent in our environment that we forget to wonder at their power and beauty.”13 The catalog for Explorations frequently used terms like “inter-thinking” and “inter-seeing”–expansions on Dick Higgins’s notion of “inter-media”–to suggest a blossoming synthetic sensibility based on formed or sensed connections.14 However, these terms were still understood by Kepes through older notions of order and organization grounded in a Neo-Kantian sensibility, rather than through the more flexible, open-ended ideas of network and system avowed by fellows such as VanDerBeek and Burnham. This difference might explain the heavily administered quality of Explorations itself, which shuttled the viewer through a sequence of interactive sensory experiences, each with a set of simple instructions, and each intended by Kepes to serve as a little perceptual lesson.

Explorations, Installation View at the National Collection of Fine Arts, Washington, D.C., 1970. Courtesy of Photograph Archives, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Further, the “crewcut teamwork” decried by Smithson was brought up again by critics, many of whom called the collectivism of the show forced or pointedly carved up Kepes’s total environment in order to evaluate individual contributions. Finally, Explorations was roundly criticized for its function as technological spectacle. The critic Emily Wasserman wrote, “More serious than the economic and organizational problems entailed during the production of this show are the ways that sophisticated technological means are merely put into the service of new forms of entertainment.”15 Similarly Tovish, Burnham, and even Arnheim criticized the glitzy content and processional format of shows like Explorations for initiating distraction rather than contemplation, and for privileging the visual effects of technology over a critical relationship to the technology’s social function. Burnham in particular disparaged the “sympathetic magic” of Kepes’s brand of technological art and his romantic notions of its social possibilities.16

Despite these disagreements, some fellows embraced Kepes’s ambitious re-imagining of the exhibition as a responsive training module for the sensory education of the viewer. Paul Earls would lead the production of Soundings (1972), a set of participatory sound installations at MIT. Michio Ihara would lead the CAVS fellows in the design of Dialogue of the Senses (1972), a tactile gallery for the aesthetic education of the blind at the Wadsworth Atheneum that routed “viewers” through a series of differentiated smells, textures and sounds. With the advent of Otto Piene as director in 1974, CAVS shifted its attentions to “public pageantry,” rather than exhibitions or static art pieces, translating Kepes’s “symbolically meaningful civic scale visual events” into elaborate celebrations. The scale of work continued to grow; Piene’s Boston Celebrations I-II (1975-76) exhibited proposals for temporary public art events throughout the city. In 1975, CAVS held Arttransition, an exhibition and conference on the “greater obligations towards the information and education of an ever-more curious public, via technology.” And in 1977-1978, CAVS fellows installed the operatic Centerbeam, comprising multiple steam projections, giant inflatable flowers, and a 144-foot long water prism, in Washington, D.C., and at Documenta 6. The ambitious production was described variously by Piene as “a house,” “an artist model for collaboration,” and “an attempt to capture the universe in a nutshell.”17 In addition to the skyward turn of these new spectacular public events, Piene also expanded CAVS’s educational mission by creating summer workshops. Under his tenure, the school of architecture also began awarding a Masters of Science in Visual Studies in 1976.

These events have their own interesting relation to our present culture of grandiose art festivals. But it is the generational differences, rather than the continuation of Kepes’s vision, that are most compelling in MIT’s new exhibition series. The recent Stan VanDerBeek: The Culture Intercom provided several points of contrast.

At the heart of The Culture Intercom, a black box plays five hours of VanDerBeek’s manic stop-motion animations. A restaging of VanDerBeek’s multimedia installation Movie Mural (1968) dominates nearly half of the exhibition space, and his early digital animations, the Poemfields (1966-71), flicker with magenta pixels the size of baseballs. The lo-fi elements of VanDerBeek’s practice slowly emerge, as do his shared concerns with Kepes. His early paintings reveal an interest in the place of “Man” in the natural elements, as well as the relationship between poetic language and poetic imagery. In the text “Culture: Intercom” (1966), VanDerBeek echoed Kepes’s ideas about a new scale of technological existence: “Technical power and cultural ‘over-reach’ are placing the fulcrum of man’s intelligence so far outside himself, so quickly, that he cannot judge the results of his acts before he commits them.”18 And his collages display a similar critical attitude toward the relationship of science, ethics, and human survival, especially as they play out in the mass media and advertising.

Approximate Restaging of Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie Mural (1968), installed at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2011. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the Estate of Stan Vanderbeek. Photo: Rick Gardner.

Nevertheless, with its cacophony of sounds and projections ranging from the most rudimentary slides and overhead transparencies to early digital animation, the enlivened installation owes more to the sensorial bombardment of the gaming arcade than to the immersive pedagogy of Kepes’s more orderly gallery experience. Though hardly John Cage’s “random situation,” ameliorating perceptual disorder was not the overriding concern of The Culture Intercom. Also missing from VanDerBeek’s body of work is the emphasis placed by both Cage and Kepes on the importance of the physical (urban) environment to the formation of healthy social bonds. He did not link the public sphere to any site or spatial surround, but depicted it as coursing spectrally through the circuits of new media–it was a social practice cleverly characterized by its scope, rather than its scale. As opposed to Kepes’s fully externalized subject, VanDerBeek’s is an emergent psychoanalytic subject appropriate to a burgeoning networked society. This new individual was metaphorically lashed to his fellow man through modern communications technologies, as well as what Deleuze might call “lines of desire.”

Against the alienation that troubled Kepes, VanDerBeek’s murals and screenings offered a collective emotional experience–live visual communication as the synchronization of dreams and the networking together of individual subjectivities. To achieve what we now might think of “crowd sourced” art, however, the artist “must find ways to come out of his isolation from his community. He must find ways to unite technology and the human condition…. He must find ways to investigate, to document, to decorate, to criticize, to love…and add meaning to the life we are all shaping.”19 This new kind of collectivity necessitated the dismantling of older kinds of group identities and coordinated production, so that “man’s senses shall expand, reach out, and in so doing shall touch all men in the world.”20

Along with Otto Piene and Aldo Tambellini’s event Black Gate Cologne (1968) on WDR television and the serialized experimental television program The Medium is the Medium (1969) on WGBH-Boston, VanDerBeek’s Violence Sonata (1970), also broadcast on WGBH, was one of the first art programs designed to develop mass culture through the new public sphere of television. Like all of CAVS’s programs, Violence Sonata was interactive, not only by inviting home viewers to call in during the performance, but also in its unusual method of broadcast. The two channel Violence Sonata, recreated in the new survey exhibition, was broadcast on two separate TV channels, and viewers were asked to move two televisions together in their own homes to watch the piece. By forming collaborative partnerships outside of the center and seeking nontraditional public venues for

participatory work, these programs also set precedents for how the success of arts at MIT would be measured.

Access to the ephemera surrounding VanDerBeek’s works, such as the schemata for Violence Sonata, opens up an opportunity to go beyond the fact of new media–television, video, and computer technology–as materials to understanding how they functioned within the imaginary of the period. The Violence Sonata ephemera includes a schematic drawing that lays out different actors in the performance, not as a sequence of events, but as a flow chart mapping possible interactions between “Man and Nature,” “Black Man and White Man,” and “Man and Woman.” Though still centered on a somewhat outdated conception of “Man” (aka Michael Leja’s “Modern Man”), Sonata sets him within a series of productively antagonistic contexts, at the crux of every node within the social network. While composing Violence Sonata, VanDerBeek had begun working with Project MAC (Man and Computer) at MIT, where the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), an early computer network that became the backbone of the Internet, supported research on artificial intelligence.

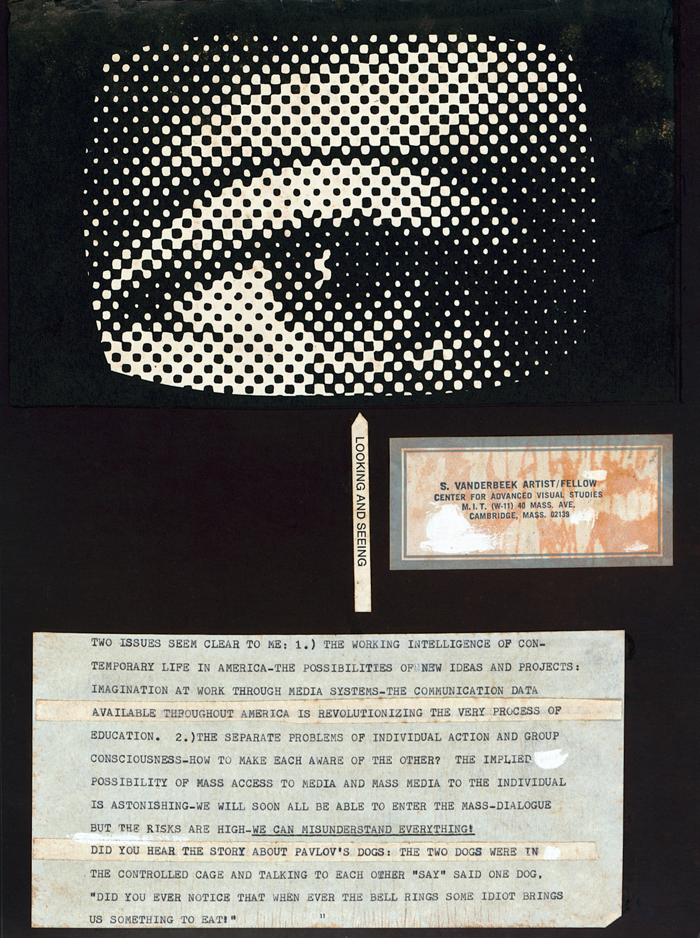

A further look at the History of Violence in America (1970), collaged layouts for a publication intended to accompany Violence Sonata, reveals yet another networked subject emerging from Kepes’s Organization Man. Pasted prominently among pictures of historical imaging technology (and even a quote by Herbert Read declaring the necessity of educating the senses) is a yellowing business card identifying VanDerBeek as an “Artist/Fellow” for the Center for Advanced Visual Studies. That same year, VanDerBeek ruminated on the position of the artist/fellow in the pages of Gene Youngblood’s seminal Expanded Cinema:

This very business of being an artist-in-residence at some corporation is only part of the story; what we really want to be is artist-in-residence of the world, but we don’t know where to apply. Major internationalizing by artists is going to become very important, and so will the myth-making process. What we’re looking for in some sociologically appropriate way is a third side to each confrontation: a way to deal with each other through a medium…. We only see each other through the subconscious of some other system.21

Stan VanDerBeek, The History of Violence in America (detail), ca. 1970. Collage on paper, thirteen works, 11 X 14 inches each. Courtesy the Estate of Stan VanDerBeek.

VanDerBeek went so far as to write a proposal for this worldwide residency position in 1969. In reality, he made a lifestyle out of temporary appointments, whether as an adjunct faculty member in studio and film departments, or as artist-in-residence at television stations (WGBH-TV, WNET, KHCT, and Kentucky Educational Television) and for the federal government (NASA, the U. S. Information Agency, the International Communications Agency).22 That business card provided him with a new professional identity–when, after all, did artists start carrying business cards?–and facilitated his movement within a world that increasingly held no permanent place for him. VanDerBeek’s artist was a mediator too, a fixer, or as he wrote, “a third side to each confrontation,” brought in to realign the funhouse mirror of mediating systems. This networked and networking status was by no means exclusive to VanDerBeek, as today’s young residency-hopping artists are well aware. But while today’s residencies are typically sponsored by museums and other nonprofit agencies, at the end of the 1960s, hosting institutions were as often corporations as museums. Smithson himself had served as an artist-consultant to the architecture firm Tippetts, Abbett, McCarthy, and Stratton in 1966, and in the case of Billy Kluver’s Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), short-term collaborations with consulting engineers addressed artist-posed problems. Neither fully within or without an institution, the artist/fellow was akin to the freelancer or management consultant–a profession begun by an MIT chemist, Arthur D. Little in the late nineteenth century that reached full flower during the 1960s and 1970s, with Boston as its hub.

Like his business school counterpart, the artist/fellow was an external element brought in to tackle specific problems within a larger institutional mandate. Whereas the business consultant was called upon to make a company more efficient, the artist was called upon to make it more humane. No longer engaged in the systematic art-research imagined by the generation of moderns that preceded them, young artist-residents at the opening of the 1970s began to function as singular competencies, briefly congregated. As the years went on, CAVS residents became more and more diverse, and as they did they resembled less and less the team of laboratory researchers Kepes had imagined, focusing most recently on the project of “examin[ing] the relationships between science technology and contemporary culture.” In the past year CAVS merged with the newly formed Program of Art, Technology, and Culture (ACT). The department dropped “visual studies” in favor of a program title that referred to the overlapping fields represented by faculty research and that pointed to its links with other programs.23

The pressure to create numerous external links–personal, disciplinary, and professional–now exists at the departmental and institutional levels, being one measure of the importance of these entities to public life.24 The idiosyncrasies of CAVS and its self- conscious relation to technical and business practices make it a quintessential example of practices less self-consciously adopted elsewhere. One would not be surprised to meet a young VanDerBeek, business card in hand, in our current age of artist nomads nourished on the constant stimulation and newfound relationships that each three-, six- or nine-month residency offers, as well as on their modest stipends. Particularly for young artists without the protective affiliation of a gallery or other home institution like the academic department, such autonomy yields flexibility but also vulnerability. The reality of the intellectual sharecropper bereft of a secure position, who works land to which he holds no claim, is one all too familiar to artists and academics alike.25 While we might not mourn the end of Kepes’s pretentious artist-researcher, one wonders what might be lost in the seasonal production dictated by the residency schedule and the homelessness of today’s artists-in-residence to the world.

Melissa Ragain is a PhD candidate at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.