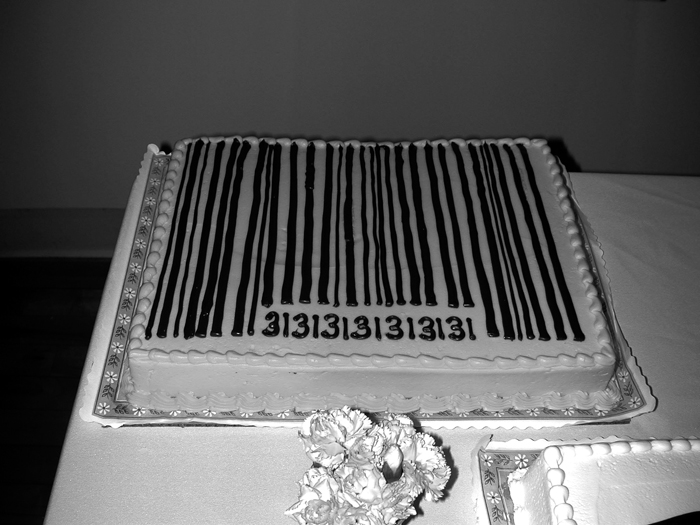

David Robbins, Ice Cream Social Barcode Cake, Pittsburgh, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Did your project, the Ice Cream Social, start with an association between the name of the ice cream company, Baskin-Robbins, and your own name?

David Robbins: That name blur was a part of it, sure. People sometimes thought that my family owned the company. There’s no connection, but I let them think so, since their confusion enhanced the project. Various levels of identity confusion permeate the Social from the very beginning. In addition to the name blur, I had personal memories of my parents taking me to Baskin-Robbins for ice cream on a hot summer night, as I’m sure many baby boomers share. Baskin-Robbins is a post WWII phenomenon; its presence in American life dates from the late 1940s and the ’50s. But the deeper connection I felt to Baskin-Robbins centered on the decor of their “ice cream parlors”–the shops where they sold the ice cream. The place had a kind of hypnotic effect on me, almost an out of body experience, triggered by the decor motif of two dots, pink and brown–strawberry and chocolate–on a field of white, vanilla. The decor’s reference was, I’m quite sure, to the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, where the ice cream cone was invented and popularized. Baskin-Robbins’s American Victorian architectural motifs, P.T. Barnum font, and references to the invention of baseball, all conjured up turn-of-the century America and was obviously a very canny design decision. Walking into a Baskin-Robbins was meant to activate a chain of associations with a phase of American history, filtered through pop design. All these layers were present for anyone who walked into a Baskin-Robbins Ice Cream Parlor, but for me the silly name connection, that Robbins hook, activated it in a special way. All these American references and layers of memory, distilled down to the simple dot.

The Baskin-Robbins company abandoned the dot symbol a decade or so ago, along with the pink, brown, and white color scheme. The company just tossed out the amino acids of American pleasure! Obviously they didn’t understand what they had… But their decision just reinforces the elegiac quality of my project.

HUO: The Baskin-Robbins dot is your personified abstraction, like Buren’s stripes or Toroni’s empreintes?

DR: Yeah, the same way that, say, a certain kind of wallpaper motif will represent a certain phase of European history. Those dots… Why does everyone like dots? I think it’s because the dot is shorthand for wit. The dot began as a mark, as evidence of a human presence–very primordial, existential mystery, all that–but it’s the mark stylized, evened out. The dot is the sign for the moment that we discovered wit. That’s why it represents Fun to us.

David Robbins, Ice Cream Social Barcode T-Shirt Design, 2003. Courtesy of the artist.

HUO: As Philippe Parreno says, “La chaine est belle!” How did you go from your first Ice Cream Social, held in a Baskin-Robbins in Manhattan, to a novella and then a TV pilot? Was it clear to you from the beginning that the project would have another temporality that is not the temporality of an exhibition, biennale, or gallery show?

DR: Definitely. For instance, in the first Ice Cream Social, I was inventing an experience specifically in order to write about it, as opposed to just sitting at the keyboard and inventing it as fiction only. It wasn’t the first time I had worked like this. I had been investigating a fiction/non-fiction blend, arranging adventures in dubious or unstable realities–actions such as going fishing by myself on Loch Ness, which I had done a year or two before that first Ice Cream Social. I was creating situations that activated fiction’s suspension of disbelief while actually carrying them out in the real world, doing things in which the plausibility was unstable while the action was quite real.

Rightly, this instability would be manifested in the form, too. The Ice Cream Social novella, first published in 1998, embeds a straightforward account of an actual event that took place in a Manhattan Baskin Robbins in 1993–what I said that night, what was said by the people there–into a literary fiction. What genre of book is that? I don’t know.

HUO: It isn’t the book that produces the reality but rather the reality that produces the book!

DR: This was undoubtedly the influence of one of my old bosses, George Plimpton, who pioneered what he termed “participatory journalism.” You go pitch for the Yankees then write about it. My approach was to combine that with art thinking to produce a dynamic between forms. And while George attached himself to an existing theater–professional baseball, for example–in order to get his material, I made the theater that I wrote about. It’s a big difference.

The live events produce experience, then, that I could write about, while the book produces certain ideas that I could later enact in real space and real time live events. It shifts back and forth, according to opportunity and to the most efficient way of realizing a particular idea. How much reality does a particular idea need? It’s a packaging issue. Form and format can change. And that enables you to advance on multiple fronts, according to opportunity.

HUO: And afterwards came the Sundance pilot, based on the TV show described in the last third of the novella?

DR: There were three Ice Cream Socials in between the publication of the novella and shooting the Sundance pilot: 1998 in Chicago, 2002 in London, and 2003 in Des Moines. These were traditional socials, serving cake and ice cream to all comers, but they also had another, more self-conscious layer, thematized in the cake designs, attire, and decor. Ice cream socials form temporary, artificial communities. In my Socials I wanted to emblematize that community. It’s like throwing a party with a party theme!

HUO: And each one was different?

DR: They got bigger and more elaborate. I built up the Ice Cream Social vocabulary, adding decorative, theatrical and musical elements. I couldn’t just keep offering stylized cakes and ice cream to people, there’s nothing to be learned from doing that, so I had to explore how to entertain them in other ways. I wrote a play about the history of ice cream, for instance, and we performed it in Des Moines. I also began inviting volunteers from the audience to come forward, introducing them to each other–because, well, it’s a social, right? Given the context, it was the natural thing to do, but we stylized it, made it a stage act. Through little experiments like this I found out what an Ice Cream Social contains, as content.

HUO: You tested it out.

DR: Everything kept feeding the progress of the project, what it was, what it could be…. Then, out of nowhere, an opportunity to make a TV pilot for Sundance arose. In 2003, I was having dinner with some friends in Milwaukee and they mentioned that they’d seen an announcement about some competition that the Sundance Channel was sponsoring–proposals for new TV series. At the dinner I actually announced that I was going to win–how’s that for confident?–and a month or so later I won! The Sundance pilot, which presented a stylized ice cream social that combined aspects of Laugh-In, American Bandstand, and a talk show, came out of the novella, part of which focuses on the creation of just such a TV show, and I also tossed in some of the theatrical elements that I’d developed in the various live Socials. After we shot the pilot–co-directing it with Sarah Price, a documentary filmmaker–I wrote a feature movie script adapted from the novella, about the gestation of this weekly TV show, which I imagined to be wildly popular!

HUO: Was the pilot aired?

DR: No, unfortunately. Not wildly popular, I guess! Actually, when I won, I didn’t know that my eight-minute mini-pilot was material for a show called TV Lab, which was itself a pilot. And Viacom, the parent company of Sundance Channel, didn’t approve the TV Lab pilot. A pity. But it was still a wonderful experience, and it’s been shown a lot since then. The pilot’s public life is just beginning.

David Robbins, Ice Cream Social Flag Cake, Chicago, 1998. Courtesy of the artist.

David Robbins, Ice Cream Social Flag Cake, London, 2002. Courtesy of the artist.

David Robbins, Sundance Channel Pilot, Flag Cake, 2003. Courtesy of the Artist

HUO: Theater, books, TV shows–is the Ice Cream Social about the appropriation of different forms, or different forms of appearance of the same idea?

DR: It’s more about inventing a context. It’s not about bringing things into art, that Duchampian thing. Instead it’s about making a new context for cultural production and presentation. I’m not really interested in the problems of art anymore. The Ice Cream Social is about absorbing forms and reconciling them, letting them coexist… It’s also about respecting the specificity of the forms you’re absorbing. If you’re gonna write a novella, well then you write a novella. It can be an artistic, experimental novella but it has to be well-written. People have to be able to get through it! Which means that as its author you have to pay attention to the classical problems of how to write an attractive sentence and structure a book. It’s a matter of showing respect for what that form can do, what it represents as an experience…. If you’re making a TV pilot, say, you have to make a TV pilot that somebody’s going to want to watch. The challenge is to make actual TV. This isn’t about privileging art over everything else, in other words. It’s about recognizing that art is good for art thoughts and television is good for television thoughts and novels are good for novel thoughts and they don’t all have to be brought into the art context in order to be validated. That’s important. A TV sitcom is as specific a format as an abstract painting. The pleasures that a TV sitcom can get to are pleasures that an abstract painting can’t.

Each form has specific virtues, that’s why it has survived. You work in the appropriate form, and with respect. Of course, the fact that it’s now someone with an art background making “television” or writing that novella means that the end-product will display more of an experimental bent. It will be informed by other knowledge and other tastes than those usually applied to making television or writing novellas. The differences will be subtle but huge.

HUO: One project taking various forms–it shares something with merchandising, no? Could you speak to the similarity and difference?

DR: In the movie business it’s understood that one of the innovations of Star Wars was that it changed the relation between a film and the merchandise associated with it–the dolls and toys and Halloween costumes and games. Prior to Star Wars, studios would wait for the movie to be a success and later bring out the toys and the dolls and the game versions. Star Wars demonstrated that, with certain kinds of films, the studios should be planning the development of the toys and dolls and games while they’re making the movie, not afterwards, and release them to correspond with the movie’s release. Make it a cultural event, not just a movie house event.

The Ice Cream Social isn’t Star Wars, obviously, but the two share an attitude toward the mutability of forms. It would in no way violate the integrity of the project to have, say, Ice Cream Social ice cream bowls. More than once my father has suggested that I contact Baskin-Robbins about adapting my Ice Cream Socials for a TV ad campaign. That would in no way damage the integrity of the project, because the project is about the movement through all these contexts, absorbing and reconciling them as it goes. In terms of content, the Ice Cream Social is far more like that old sci-fi movie, The Blob, than it is like Star Wars!

HUO: You are actually producing ceramic ice cream bowls at the Albisola Studio in Italy for the Ceramic Triennale, which happens in a small Italian village where Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni, and Asger Jorn experimented with ceramics. Albisola was also key to the Situationists gathering.

DR: It’s so funny that we’re doing this. A TV pilot, ceramic bowls–the comedy keeps expanding.

One thing that was very interesting to me from the beginning of my involvement with the art world was the idea of becoming a person who operates in the art context, the fringe, and also in the entertainment culture context, the mainstream. It’s all a matter of granting yourself full access to your own imagination. If you’re a kid raised on media, no one context can satisfy what you find in your mind. We agree to limit our access to our own imaginations in order to specialize for professional purposes, for the market, to make a living. But I didn’t want to specialize in that way. I was willing to make less of a living and have more freedom of imagination. I wanted to specialize in content production and in an attitude toward production, not in particular media or a particular context. To have human, personal sensibility override system–that’s the idea. If your imagination has been programmed by TV shows and movies and pop music and arts, you may want to try doing all of them. It might make sense to you–it might be natural to you–to communicate in all these forms. Warhol came very close to doing it, but Andy was too weird and scary for people. Also, with Andy everything had to be “a Warhol”–had to look and feel like a Warhol. And that wasn’t really a model that I was interested in. It had been done.

HUO: The beginning of the Ice Cream Social seems to correspond more or less with your growing distance from the world of art…. Can you speak to how towards the late ’80s/early ’90s you took more and more distance from the world of art and its economy?

DR: The distancing had begun a few years earlier. As early as ’89 I knew that I was not a “believer” in art. I hadn’t gone to art school, so after I started exhibiting in ’84 it took a few years to find out that I had an odd take on the art thing. Whenever I was in a group of three or more artists, at an opening, say, and they would begin to talk about art in a particular way that they all seemed to agree on, there seemed to be a kind of secret consensus that I took to be of the result of art school training. I understood what they were saying intellectually but I never “believed” it. And really I couldn’t believe that they did, either. But they did! So I was a true skeptic from the beginning, an unbeliever. And that skepticism came through in the things that I made.

Art is a faith-based practice, essentially. It doesn’t matter what form the art takes or what it is trying to say, to get the art to “go” you have to believe. If you’re willing to believe, like any other religion, then you’ll get a lot of rewards. Why would you deny yourself these pleasures, right? At the same time, a reasonable person might be uncomfortable with any endeavor that, at its core, requires belief. Art allows greater transparency than religion, certainly, but ultimately art can’t dispense with faith or else the whole enterprise collapses.

HUO: Can you tell me more about the beginnings?

DR: From the beginning of my involvement with art I was a man of pop theater, a TV kid, but I was articulating that theater via objects and images, in a context devoted to objects and images. I got the art context fundamentally wrong, and gradually built that misperception into an alternative to it. The visual art context is really designed for people who want to, or already do, seek to align their emotional and psychological lives with the neutrality of form, while theater more fully recognizes the narrative dimension of human life–tragedy and comedy. The art world is always suppressing the narrative line, looking for ways to take it out or play it down, to zero it out. I wanted a fuller embrace of the fact of narrative–we live, we die, there’s narrative–not in order to critique art but only because that position was more authentic to what I was interested in.

I was never a darling of The New York Times or of the Whitney–far from it, believe me–but there are many ways to have a career in the art world, many ways to have a valid history. Come to think of it, don’t you find it odd that whenever we think of an artist, in any field, who no longer appears active, we always think that it’s because they somehow “failed?” Really, isn’t it just as likely that they found not to their liking whatever system they were required to engage in order to get their work out–the system failed them, on the human level–and, in an act of maturity and self-possession, they moved on? Culture systems such as the art world may be all we have, but that doesn’t mean they’re good systems. From a certain perspective the art world is a deeply unhealthy network that brings out the worst in people. It’s too bad that the pursuit of beauty and knowledge should do that, but it does. The more time I spent in the art context, the more uncomfortable I became with the faith-based dimension of it. I had to invent a way out, and into another kind of creativity.

David Robbins, Ice Cream Social Clock Cake, Chicago, 1998. Courtesy of the artist.

David Robbins, Ice Cream Social, Manhattan, 1993. Courtesy of the artist.

HUO: As Alexander Dorner said in Ways Beyond Art, ” I always thought in order to understand the forces which are effective in visual arts it is important to understand other fields of knowledge.” What alternatives did you identify?

DR: It was and is a complex process. It doesn’t happen overnight, and you don’t get there with just one project. I began to move away from the specialized language on which visual art has come to depend, toward mainstream formats–books and television. Also I began to put more emphasis on involuntary responses. Comedy is an involuntary response. When something is funny, you respond. You can’t help it.

The Ice Cream Social project was an important stage for my practice because it offered a system of making that could replace the art system. It was a platform for engaging actual people in a spontaneous creative event, and marked the beginning of my movement away from object production into some kind of theater. Not art performance but, rather, a comic theater informed to some extent by conceptual art. From the start of my exhibition history, back in the ’80s, I always thought that’s what I was doing–comedies–and had long said so. The first Ice Cream Social in New York for example, started with the dumb gesture of making a dot painting based on the Baskin-Robbins ice cream company design motif, and followed through with the ridiculous idea of showing that painting in a Baskin-Robbins Ice Cream Parlor, and inviting people to come see it and eat ice cream in the dead of winter. It was comedy even if it didn’t use any of the signals of comedy to announce itself as such. It’s not nightclub comedy, but neither is it a gallery exhibition. It’s site-specific comic theater. To use an object as an excuse for theater, and, along the way, to see if I couldn’t make an alternative to the art rituals: the gallery, the opening, all that stuff–that approach was influenced by Broodthaers, who had identified the art system as a theater of rituals. How do you go about making an alternative to that theater of rituals, if that’s your aim? One option is to take some existing ritual and remake it. That was attractive to me. Of course, the event had to be something that people could understand, it couldn’t be something that was so strange it confused or puzzled people while they actually experienced it. In art, so often the point is to arrive at something that is clearly strange, but with the Ice Cream Social I wanted all the strangeness to be hidden or underneath this very friendly, normal social surface.

HUO: The mainstream is one reality that is surrounded by many realities. I see the fabric of reality as parallel universes–as David Deutsch describes it for quantum physics.

DR: I do think there’s something very attractive about the challenge of working in the mainstream, but at the same time it’s important to re-direct the mainstream towards higher goals. There’s a part in the Ice Cream Social movie script where Trace, who runs an entertainment think tank, characterizes the Cold War as “the war between Fun and No Fun.” She’s speaking honestly. The U.S. was fun and the Soviet Union was no fun. Fun won, and ever since, our culture has been an extended celebration of that moment of victory of fun over no fun. Can a culture keep doing that forever? The mainstream culture has had a problem for a while now because it seems not to know what the next step is, what the next level is…. To my mind, the next level is that you make fun substantive. Recognize that you’re basically a civilization of fun but don’t allow fun to be quite so… what?… irresponsible.

HUO: How do you make fun responsible?

DR: I think you start by recognizing that yours is in fact a culture of fun. Just by recognizing that condition, you begin to change what you need fun to deliver, how you need fun to perform. Fun starts to grow up. That’s really all I’m arguing for, through all of this. I think it’s a good idea that fun was victorious but it has to grow up. You have a generation of human beings who are born into a moment where fun was victorious, right? That’s what they know, what they recognize, and what they want. And that’s not in itself a bad idea–fun is a positive, if perhaps limited, idea of life. But too many people didn’t really understand the nature of their own culture. The baby boomers locked us into their own childhood relation to fun, and because they’re such a huge demographic their idea of what the culture should be–fun, and getting the money to have fun–has been in effect for almost fifty years now. Fun never grew up. One result, today, is that the mainstream culture has stayed directed at kids rather than adults. Because we didn’t insist that fun grow up, today there’s very little for adults that’s really satisfying in this culture, other than books, which are a classical form. The question is how do we adapt some of the newer forms and formats so that they become more satisfying for grown ups. That’s a big job but it seems to me to be a job that is worth doing.

David Robbins has had three dozen solo exhibitions in the United States and Europe. He is the author of four books, including a novella, The Ice Cream Social (JRP/Ringier Kunstverlag, Zurich, 2004) and most recently The Velvet Grind: Selected Essays, Interviews, Satires (1983-2005), published by JRP/Ringier in 2006. He has just completed writing Concrete Comedy: An Alternative History of Twentieth Century Comedy.

Hans Ulrich Obrist is a Swiss curator and art critic. In 1993, he founded the Museum Robert Walser and began to run the Migrateurs program at the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, where he served as a curator for contemporary art. He presently serves as the Co-Director, Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, Kensington Gardens, in London.