The Story Up to This Point

During the decade of the 1970s, I spent a fair amount of time in New York City. And although some of that time was spent in respectable “high-art” venues—the Met, the Frick, MoMA, etc.—a lot of it was spent in other kinds of places: tiny ephemeral jazz clubs and loft performance spaces like Studio Rivbea on Bond Street in NOHO and Ali’s Alley further south in SOHO.1 And there was plenty of other excellent music as well, for example in the punk, new- and no-wave clubs of the East Village.2 In addition, alas, far too much of my time was spent underground, hanging out while passing through the Port Authority Bus Terminal; the transit hub at Grand Central Station; the PATH stations at 14th, 9th, and Christopher Streets; and riding the trashy, dangerous, and graffiti-laden pre-Keith Haring subways.

This was hardly the New York predicted by Hugh Ferriss and other “visionary” architects working earlier in the century, who strove first to imagine and then to realize a built Manhattan embodying the essence of the block grid established per the regulations of the 1916 Zoning Ordinance, the set of regulations that essentially set the ground rules under which the first great generation of skyscrapers came into existence.3 Under the same set of regulations, New York inexorably grew into the anti-vision it was to become.

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

The actual 1970s, which we might say figuratively began on February 2, 1968, with the calling of the deeply divisive and politically incendiary garbage strike, were not kind to Gotham City.4 Although the World Trade Center opened to much fanfare on April 4, 1973, the city as often as not seemed to be spiraling out of control toward some urban apocalypse. From Harlem to the Lower East Side, the South Bronx to Bedford-Stuyvesant, huge tracts of the urban landscape remained in effect a war zone, perpetuating the memory of the race riots of the 1960s as a tangible topography of rubble. Crime, prostitution, and drug use were rampant. The entire MTA underground seemed a vermin-infested warren of dangerous tunnels encrusted with graffiti and smelling of urine and rotting garbage. And Times Square, iconic heart of tourist Manhattan, looked like Ground Zero of the porno industry and the red light district.5

The city reached the middle of the decade virtually bankrupt, prompting President Ford’s “no bail-out” speech, reported by the Daily News on October 30, 1975, under the infamous headline: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.” Happy Halloween! Still to come, the long, hot Son-of-Sam summers of 1976 and 1977, the latter marked also by the power blackout and attendant looting of July 13.

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

And although no one was as yet aware of it, the AIDS crisis lay latent across the urban landscape like a black shadow destined to bring suffering and death, along with anger, division, denunciation, and recrimination of an intensity and depth imaginable only in the darkest nightmare. Over a decade later, as he faced the brutal fact his own mortality, the artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz summarized the sense of impending doom this way, rooting the contemporary acceleration toward oblivion in the deepest past of human civilization:

When they invented the wheel they invented the collision and the darkness of what time leads the willing body into. It’s seeing how slowly we shift position from room to room. It’s the moment of recognition of an entire civilization driving forward at a faster and faster rate of speed and we are asleep at the wheel and the impact is not so far ahead.6

A Strange State of Grace

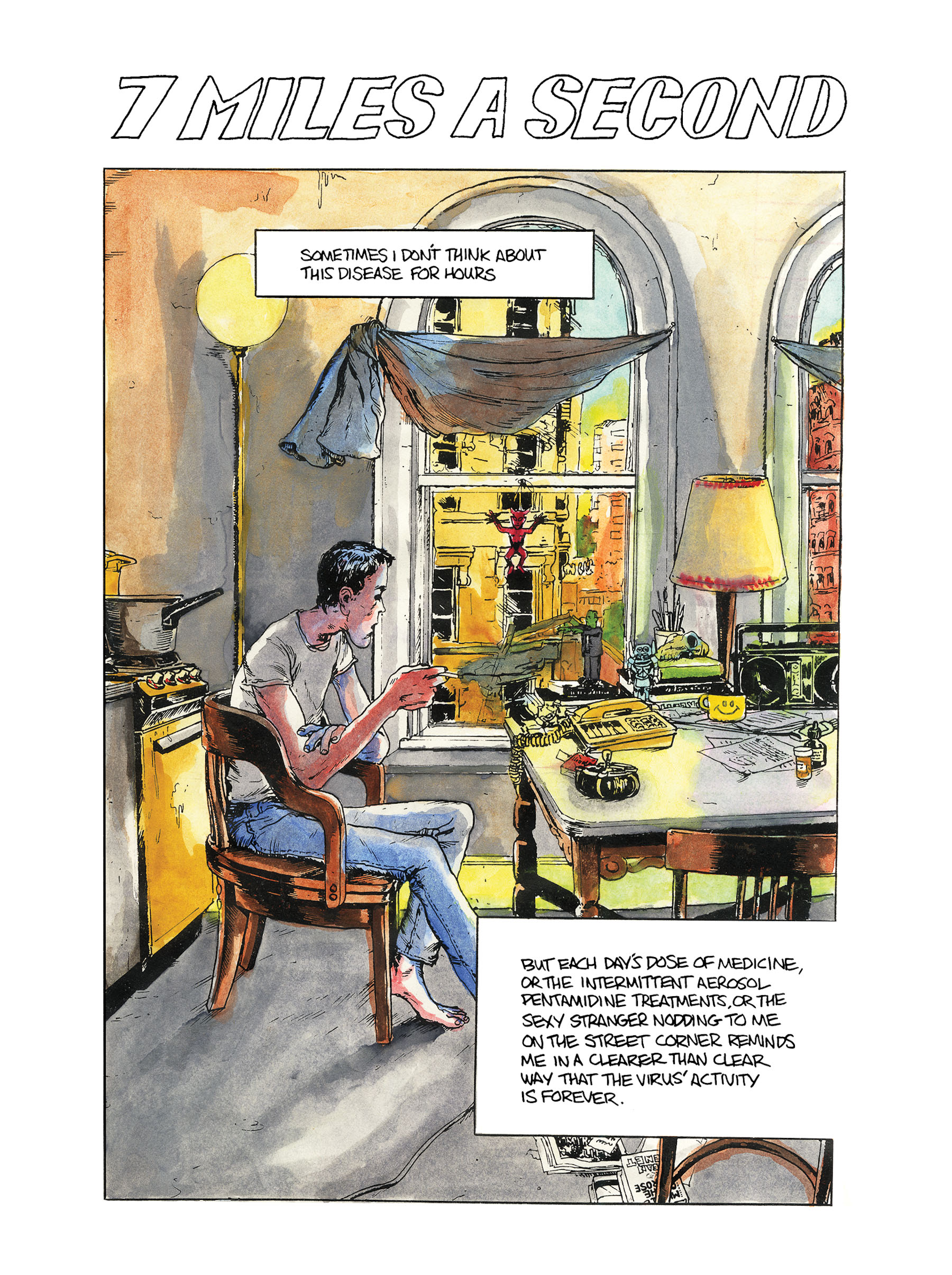

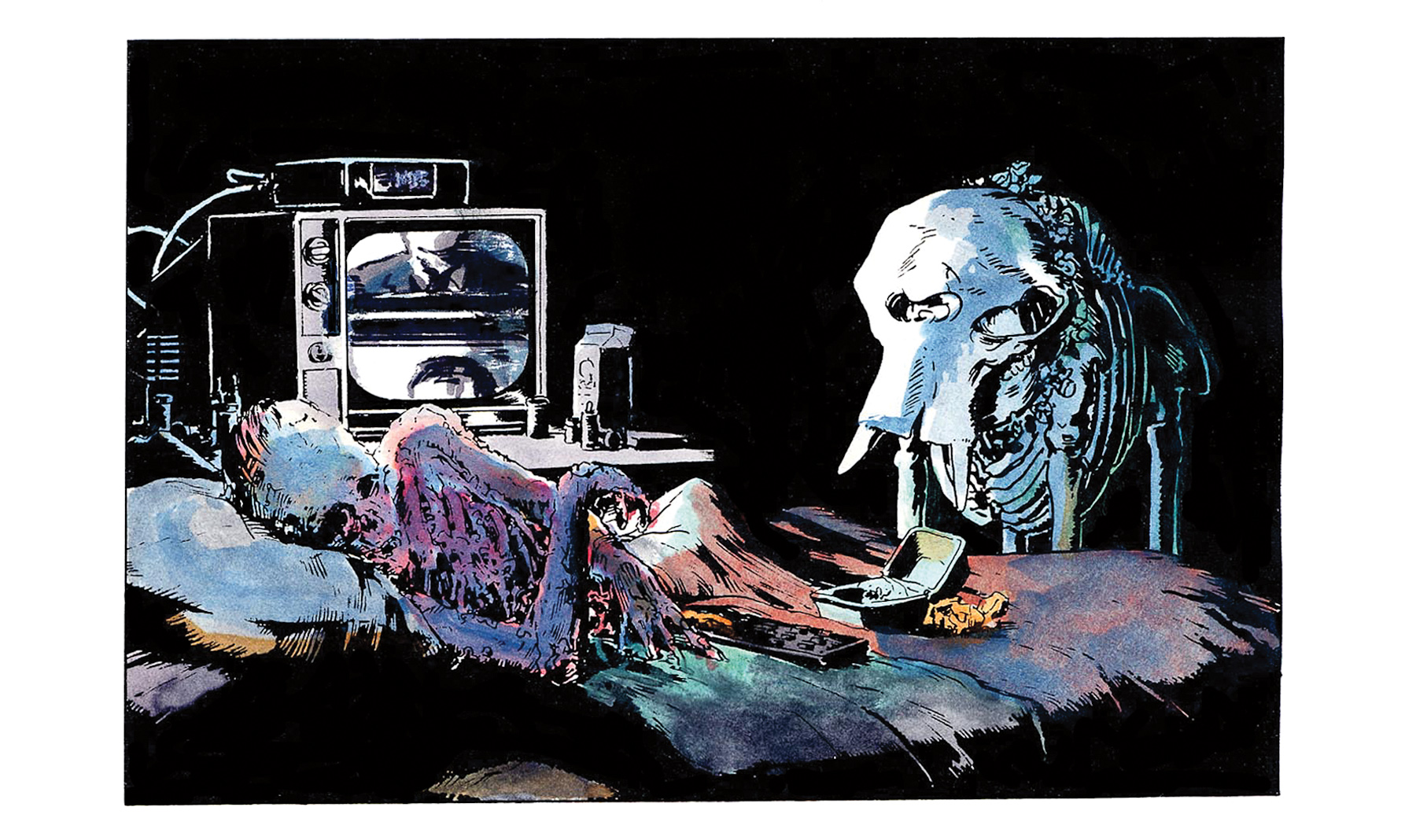

“David Wojnarowicz died of AIDS on July 2, 1992, at the age of thirty-seven.”7 The graphic novel 7 Miles a Second was among his last works. The collaboration with James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook was in fact still unfinished at the time of his death.8 In the catalog for Wojnarowicz’s 1990 retrospective Tongues of Flame, it appears as a work in progress.9 It was finally and originally published in comic form under the DC Comics Vertigo imprint in 1996. The 2012 Fantagraphics hardcover reprint both restored pages missing from the original Vertigo edition and enhanced the color with reference to Van Cook’s original watercolors over Romberger’s line art.10 The book is divided into three parts. The first two deal with David’s teenage life as a hustler on the New York streets. The third deals with David’s then current life, a life lived under the sign of AIDS, a life spent sitting in his apartment with a long lanky body folded a bit awkwardly into a wooden chair, smoking a cigarette, staring out the window. “Sometimes I don’t think about this disease for hours. But each day’s dose of medicine, or the intermittent Pentamidine treatment, or the sexy stranger nodding to me on the street corner reminds me in a clearer than clear way that the virus’ activity is forever.”11

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

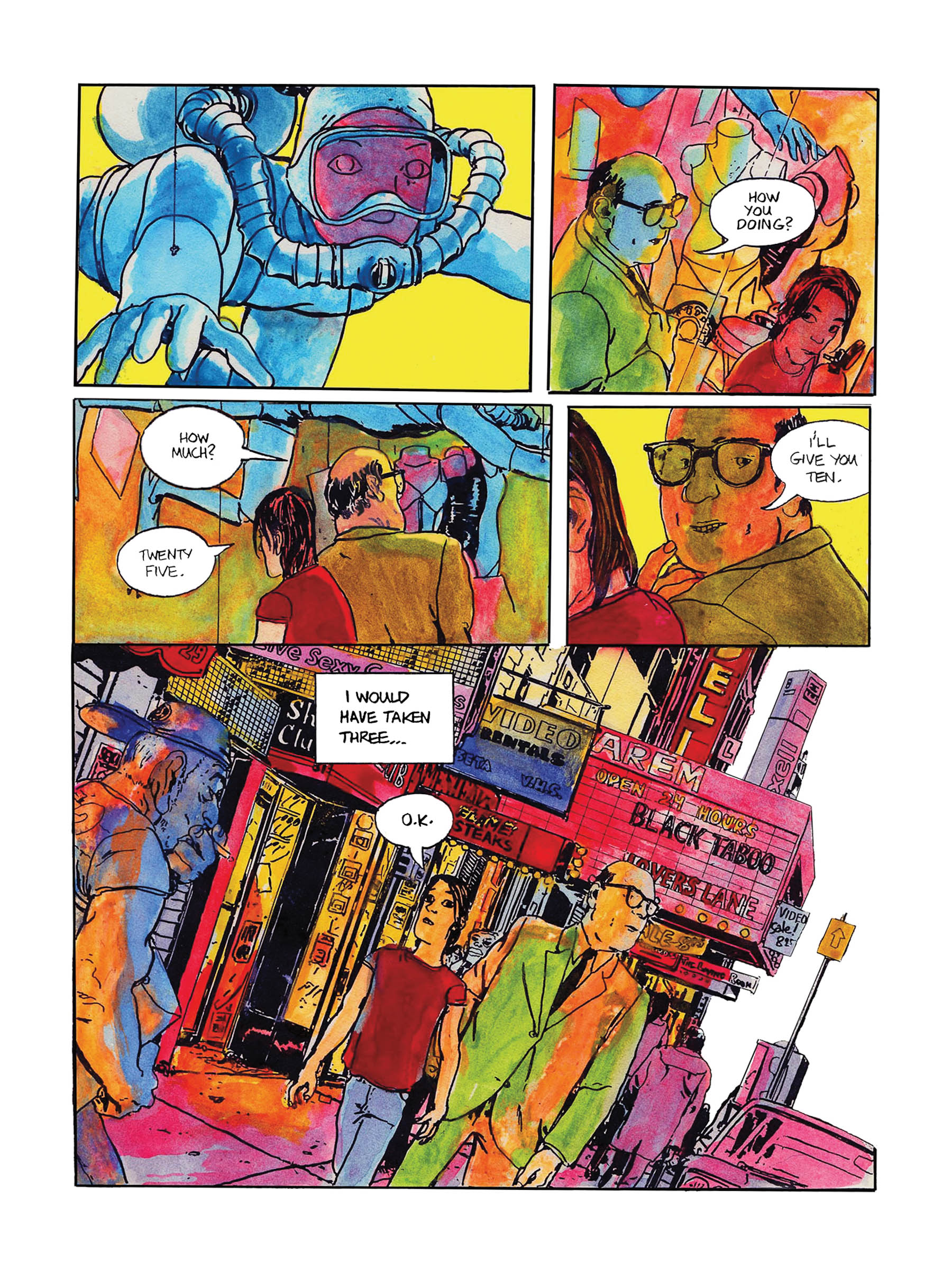

Before the virus, however, there was the hustle. Hanging in Times Square, waiting for a pickup: a balding and bespectacled middle-aged guy who needs to keep his proclivities “for all those beautiful kids” carefully segregated from “an outstanding job and a wonderful family that I really love.”12 The sex, transacted in a sleazy by-the-hour hotel, is oral (with David the passive recipient) and typically sordid: “It was really the old guy’s trip that I watch” [through a chink in the wall giving access to the room next door] while “a prostitute that I recognized from in front of the Port Authority” provided sex to a customer so jaded that he seems unaware of the horrible wounds that slash across the hooker’s breasts and belly. It was “like he couldn’t conceive of pain attached to the body he was fucking.”13

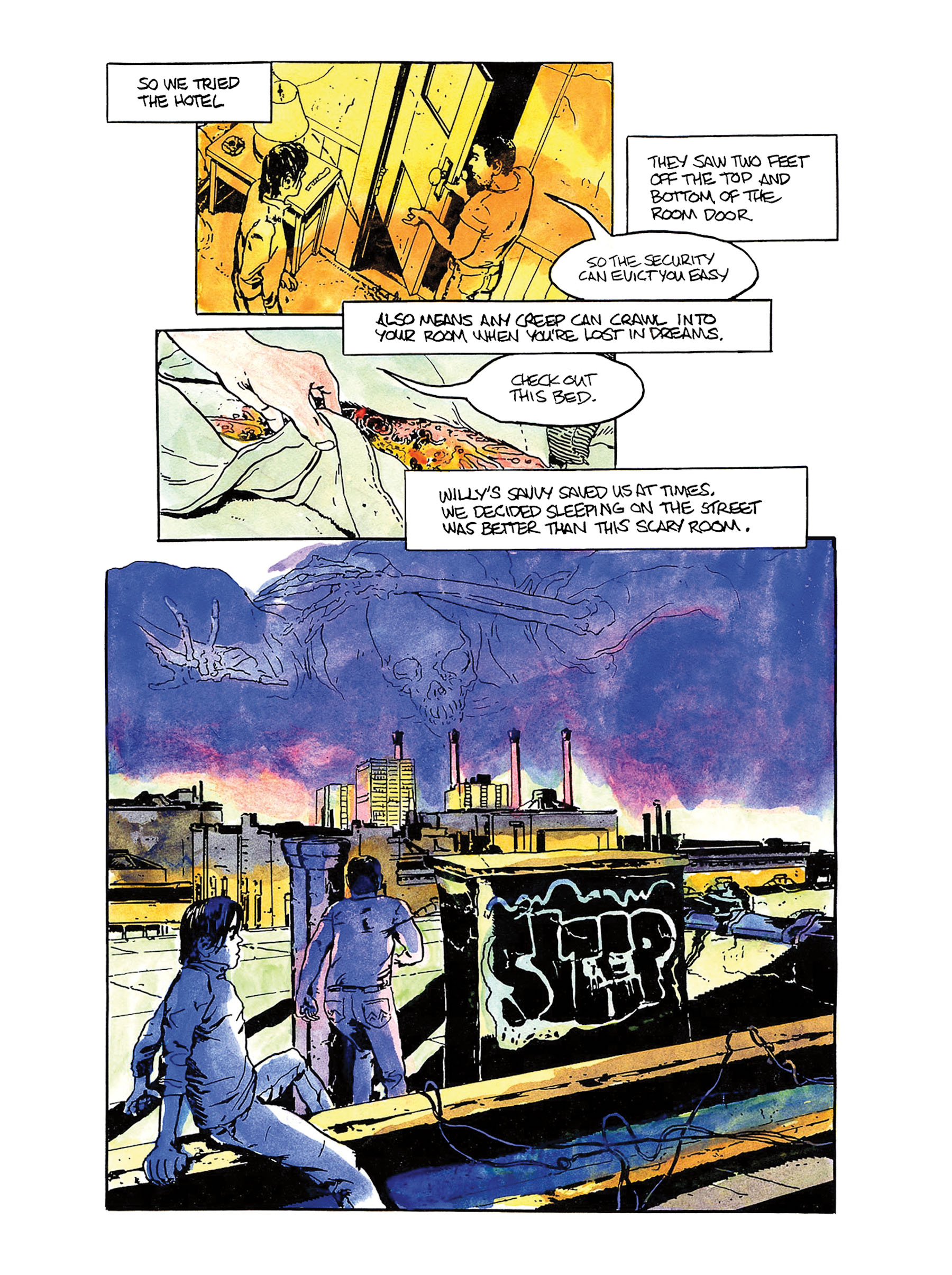

David, on the other hand, lives in a world of perpetual pain, hunger, sleeplessness, hallucinatory violence, and degradation. Eventually, so strung out that “[he] couldn’t even hustle anymore,” he runs for a while with a buddy, “Willy,” someone he’d “met…in a halfway house for ex-convicts.” “In prison he’d spent eight years in the unit for the criminally insane because he’d tried to kill his foster parents with rat poison. This was after they locked him in the attic for a month while they went on holiday.”14

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

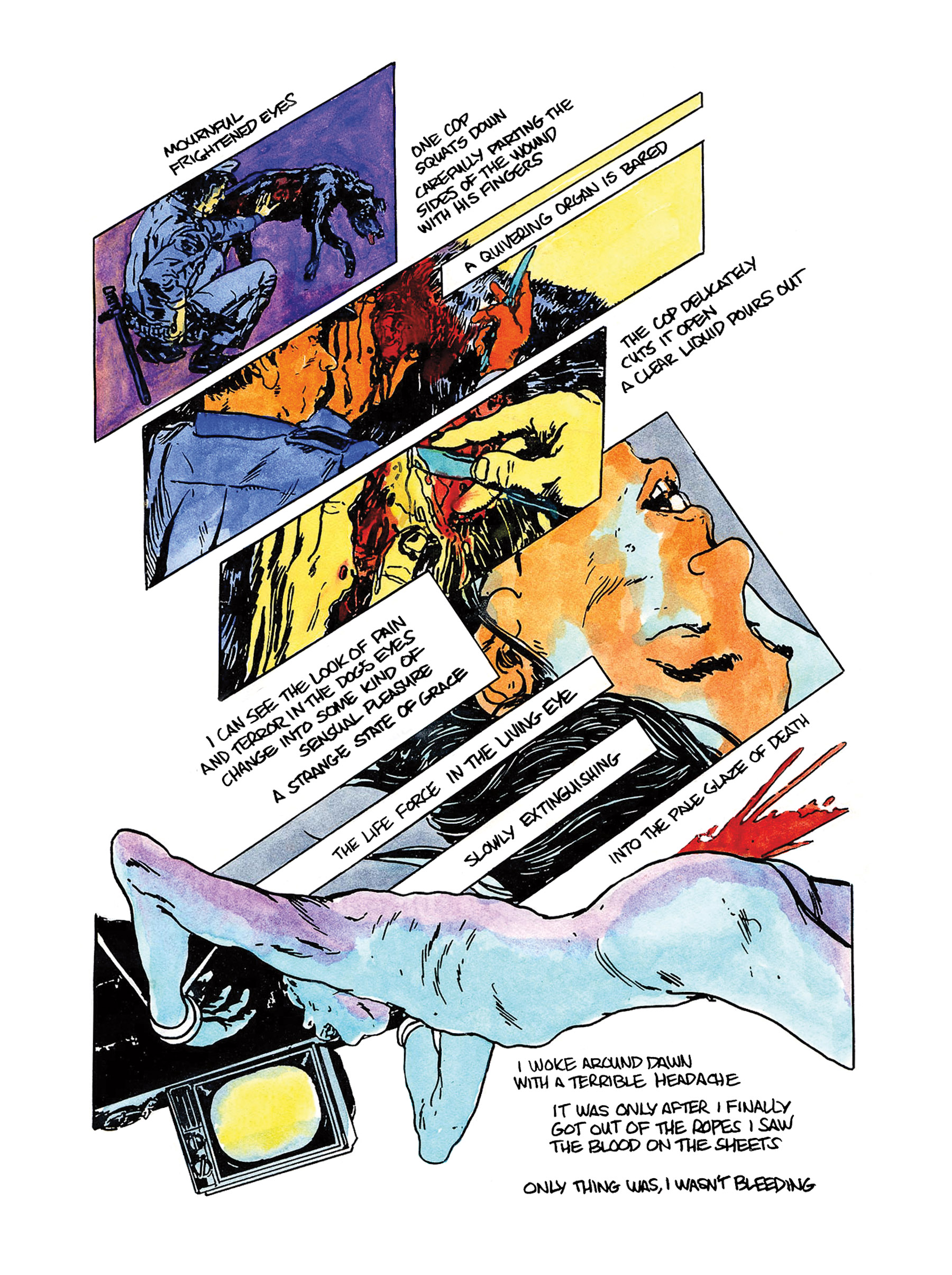

Eventually, while he is drugged, trussed up, and brutalized by a sadistic trick, David experiences an ecstatic hallucination, a dream state that fuses pain and pleasure in a way uncannily and brutally reminiscent of a religious ecstasy of the sort described so vividly by Saint Teresa of Avila.15 In his own dream, his own ecstasy, David imagines himself in the subway. Standing on an empty platform, he sees a bum on the tracks, “a grimy figure…pacing back and forth his hair hanging like garlands from his skull.”16 As portrayed by the artists, he seems almost to be dancing. Miraculously, however, the “grimy” bum becomes a snarling, terrified black dog, shot down by three policemen. And then, the miracle redoubled, dog and David become one as a sacrificial ritual unfolds:

One cop squats down carefully parting the sides of the wound with his fingers. A quivering organ is bared. The cop delicately cuts it open. A clear liquid pours forth.17 I can see the look of pain and terror in the dog’s eyes change into some kind of sensual pleasure,18 a strange state of grace. The life force in the living eye slowly extinguishing into the pale glaze of death.19

Later, in another visionary dream, visually cued for us by a reprised close-up of the ecstatically unconscious David, we are immersed in a similar experience, similar and yet transformed, transfigured: a bum’s ballet enacted, not this time in the dark and noisy crypt of the subway, but as if in the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles, in a world where architectural solidity is dissolved in light and enveloped in silence:

I’m in a hallway lined with people sleeping. All of them look like they have no home or money. I walk to the end of the hall and I see this is a mansion. Outside the windows it’s winter, and there is the clearest light I’ve ever seen. I stand there unable to move, the light is so beautiful and where it falls across the marble floor there’s the grubbiest bum I’ve seen doing this slow and wonderful dance. Slowly turning round and round with side to side swaying motions, saying nothing at all.20

An apotheosis of life on the street, the bum has nowhere to fall but up, into a world of heavenly silence and light. But for all its overtones of saintly transfiguration, this is after all, as a part of Wojnarowicz’s own narrative, only a kid’s ecstatic vision. Drained of the insoluble entanglement of pleasure and pain that so complicated the earlier vision of sacramental [self-]sacrifice, it can at best provide a beautiful interlude, a sanctification of the world in pure winter sunlight before our inevitable return to the nightmare darkness of “this killing machine called America,” where “fags and dykes and junkies and the poor are expendable,” and where David Wojnarowicz must eventually live and die.21

The text of 7 Miles a Second derives entirely from Wojnarowicz. Much of it is quoted, excerpted, or otherwise recapitulated from already published work, including the collection of apparently recorded monologues that, after a number of changes in publication, is now known as The Waterfront Journals; Wojnarowicz’s “Memoir of Disintegration,” Close to the Knives; and essays and incidental writing re-published in the Tongues of Flame catalog.22 Because that writing taken in toto is so scintillant, raw, observant, self-reflective, so weirdly innocent, and wonderfully wise, 7 Miles a Second is a compelling introduction to a much wider body of extraordinary written work. Wojnarowicz’s writing can be painfully direct and graphic, then achingly and soaringly poetic (a characteristic often described as “surreal” or “psychedelic,” both of which seem too pat and hence demeaning). He is, I think, essentially a realist, at times down and dirty, at other times magical. Especially in Close to the Knives, his anger is pointed and palpable: a rage focused and directed toward action. He makes most of the Beats seem a little aestheticized, even a little self-serving. On the other hand, the 7 Miles a Second script can certainly stand on its own as a series of self-contained units without the need of any outside critical apparatus.23

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

The art presents an entirely different set of issues. Although not explicitly spelled out by Carr, it seems likely that Wojnarowicz approached Romberger and Van Cook (apparently initially through the former) with his comics project because the couple had previously worked in that medium. Their own strip, Ground Zero (written by Van Cook with line art by Romberger), had appeared in a number of ephemeral East Village publications. Wojnarowicz’s project, however, was not simply to be an ironic look at the Ground Zero of life in the East Village, but rather a “story of his life” told in comic form “so that young gay people would realize that there was someone who’d survived the things they were going through.”24 His own art, although obviously influenced by the visual and stylistic language of comics, was in general nonnarrative, building up meanings through significant juxtapositions of an initially restricted vocabulary of signifiers, then later (as his work matured) through the addition of increasingly sophisticated overlays and interpenetrations, employing of an ever-wider repertoire of reusable images.25 Even his film work was structured in this resolutely experimental way.

Romberger and Van Cook brought the prose narrative to life. In the first story, “Thirst,” about life as a hustler on Times Square, the narrative structure is fairly straightforward, although even here there are some nice cinematic effects and clever visual inter-cutting between disparate narratives. As the work progresses, however, the structure becomes looser, less tied to the conventions of linear narrative, more magical, less gritty—except at those points where the brute fact of death renders magic null and voids all its effects. A beautiful example of this strategy occurs in the small panel on page 57, where David’s character is pulled back from a vision of “outrun[ning] my own existence [and] the terrible weight and responsibility of my own body,” by the simple suggestion, “David…look at Peter.” Peter, having just now breathed his last, lies dead, his ghastly face framed against a grey wall, a brilliant burst of orange flowers at the left of the panel mediating the passage back into the orange-yellow explosion of David’s shattered vision.

Although Peter Hujar died at home, while the novel’s previously unnamed character brutally wastes away in hospital, it is hard to escape the conclusion that this one drawn-out death—metonymically standing in for the death of a whole generation, a whole community, an entire world—must be that of the seminally important photographer Hujar, David’s closest male friend and mentor. The face of the corpse, as drawn by Romberger, and the visage of the dead Hujar, surreptitiously snapped by Wojnarowicz almost immediately after the passing of his friend, are uncannily similar.26 If nothing else, both Wojnarowicz’s photo of Hujar dead and Romberger and Van Cook’s “Peter” belie the notion that living eyes alone can function as “windows of the soul,” perhaps even the idea that the “soulless” dead are but empty vessels. Bereft of life, the eyes still articulate a particular and personal being, unless, as Wojnarowicz seems to suspect, they are eventually resolved as “broken window[s],” no more than “glass…disappearing in rain.”27

Moments Lost Like Tears

All in all, Romberger and Van Cook have done a brilliant job translating Wojnarowicz’s prose into the medium of the graphic novel—and if I have stressed Romberger’s contribution, let me redress that balance now. Van Cook’s watercolor washes can be either wonderfully subtle, or in-your-face brutal. They are absolutely integral to the overall effect; they set the tone of the pieces with elegant precision right from the very first full-page panel of “Thirst” that opens the book; and in an important way they are what binds Romberger’s wonderful line art into a smoothly flowing or explosively disruptive whole. (It’s no wonder DC had trouble providing an adequate translation of her work with the comic printing technology available to them in the mid-1990s.)

In collaborating with David Wojnarowicz, Romberger and Van Cook were working with an artist whose style was unmistakable and who produced any number of works that provide us with a searing archive of personalized images. These images relate both to his personal life and to the wider world of the first generation afflicted with AIDS and the nascent political and medical power of groups such as ACT UP, with which he became increasingly involved. Yet Romberger and Van Cook do not simply attempt to translate Wojnarowicz’s vision into a viable comic book structure (probably a fool’s errand in any case). Rather they recast his world, as embodied especially in the prose, in a way that fits perfectly into the commercial language of comics, even as it pushes the boundaries of that idiom.28 At the same time though, and this is the genius of their work, the world they evoke seems absolutely to be Wojnarowicz’s world. David is beautifully realized as a character: tall, thin, and horse-faced; full of false, or at least tenuously held, bravado and a kind of weird innocence as a kid; moody and self-reflective; potentially angry and violent; a committed smoker; a rebel “born into a preinvented existence within a tribal nation of zombies”;29 and a young man who confronts his own imminent death, if not without fear, then with a uniquely personal set of insights. These insights capture two radically distinct perspectives, yet they appear to be intrinsically linked aspects of Wojnarowicz’s complicated worldview.

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

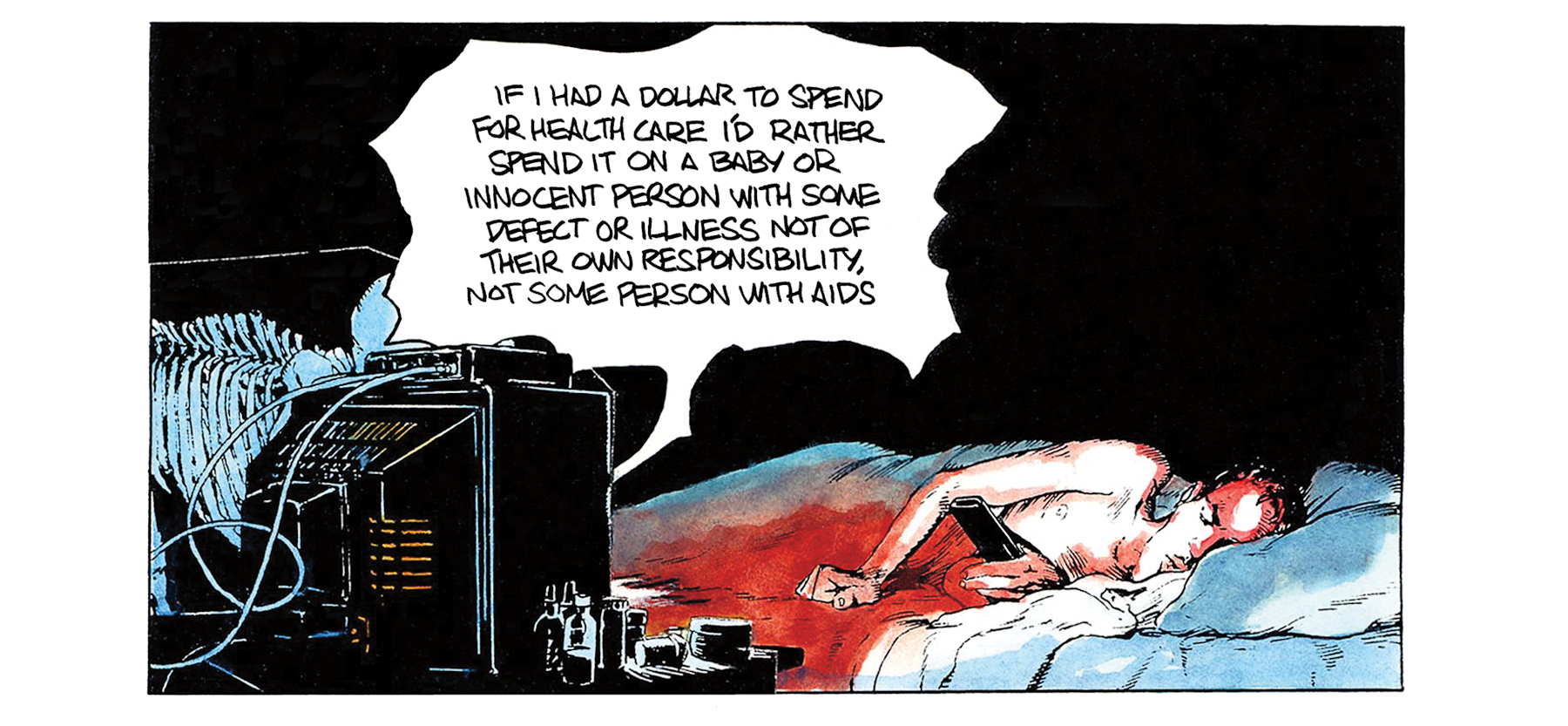

The first of these perspectives articulated in the book is explicitly political and grounded in rage: not simply rage at the fact of a life cut tragically short, but also rage at the fact of a life reviled to its end, rage at the fact of a life whose tragic shortness entails the blindness, the complicity, the hatred, even the exultation of others.30 This rage is directed at politicians, at the (Catholic) Church in particular, at the government health care bureaucracy (both local and national), at the NIH and the FDA. It finds release in David’s increasingly intense involvement with radical groups like ACT UP, as well as in fantasies where the energy unleashed by rage is channeled into the power of personal and massively destructive revenge. These issues crop up again and again in the latter section of 7 Miles a Second; but for his most brilliantly excoriating text, accompanied by relentlessly powerful art, see the section that begins “I wake up with intense nausea…” and culminates with his “three hundred seventy foot tall eleven hundred thousand pound” avatar commencing the destruction of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, seat of the hated and unabashedly homophobic Cardinal O’Connor.31

For Wojnarowicz, however, rage at the fear that breeds violent and institutionalized repression, the utterly dehumanizing drive toward “silence and invisibility” (and death) is linked inexorably, as to its opposite, to a desire that culminates, finally, in love.32 Seen from that perspective, death represents a moment of final sundering, the cutting of ties to all those you have loved, taking “love” in all its varied and divergent meanings: from guys picked up for a quick but passionate blow job down on the rotting piers of the East River waterfront to a long-term partner (in David’s case, the East Village anomaly Paul Rauffenbart) with whom one shares one’s entire life: sexual, intellectual, emotional, spiritual. Despite his volatile personality (Carr’s biography is chock full of angry break-ups and tearful make-ups) and his natural reticence, David Wojnarowicz had lots of friends,33 and hence lots of ties to sunder.

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

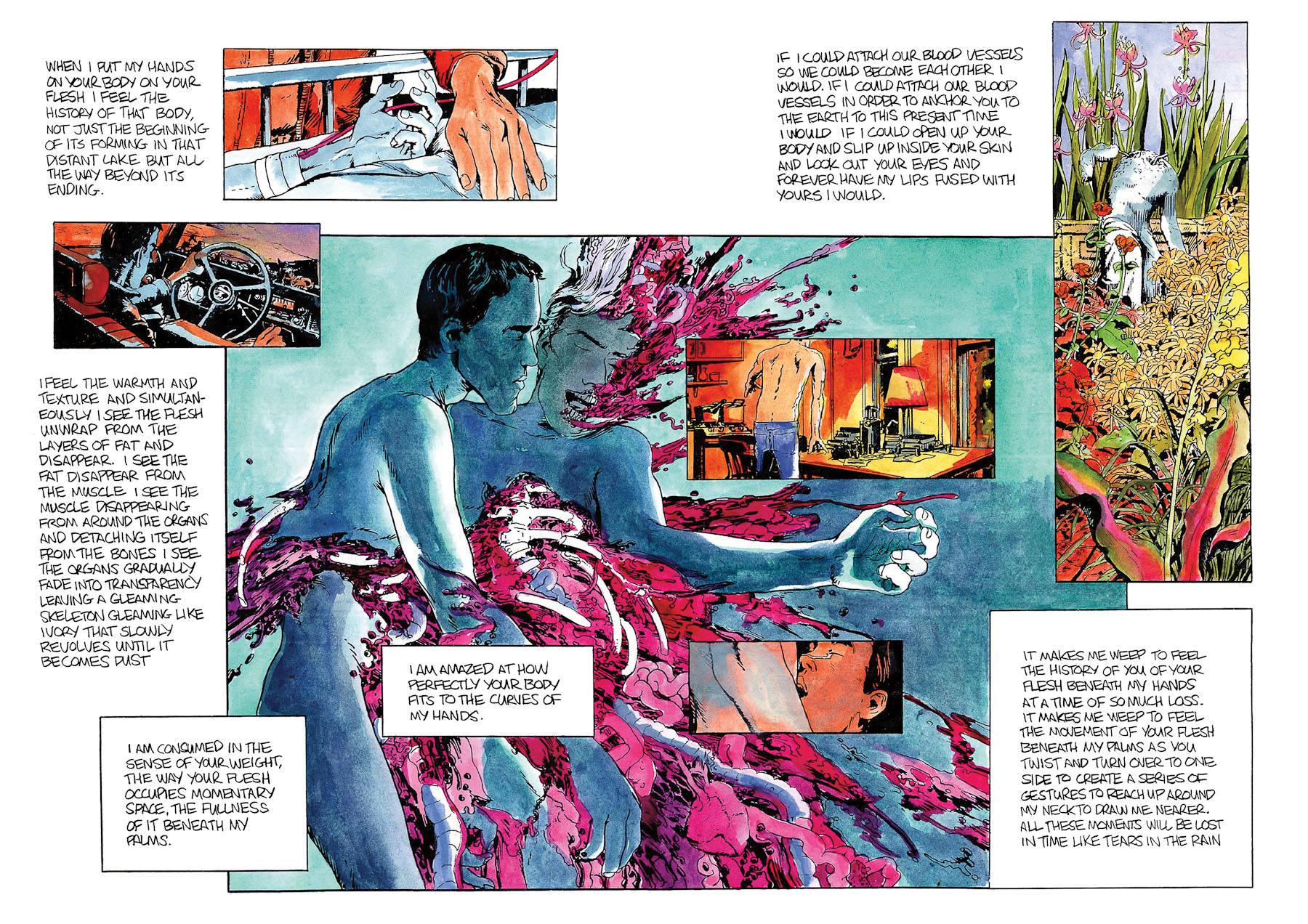

And it is in terms of one such relationship, and its inevitable end, that David produced one of his most intense and moving texts, which begins: “When I put my hands on your body on your flesh I feel the history of that body, not just the beginning of its forming in that distant lake but all the way beyond its ending.”34 In 7 Miles a Second, Romberger and Van Cook visualized that text primarily as an explosive, passive yet violently transgressive attempt at the melding of two bodies cast in ghastly blues, purples, and magenta around a fragmentary gleaming whiteness of bone.35 In that way, they follow out the history that Wojnarowicz describes:

I feel the warmth and texture and simultaneously see the flesh unwrap from the layers of fat and disappear. I see the fat disappear from the muscle I see the muscle disappearing from around the organs and detaching itself from the bones I see the organs gradually fade into transparency leaving a gleaming skeleton gleaming like ivory that slowly revolves until it becomes dust. I am amazed at how perfectly your body fits into the curves of my hands. I am consumed in the sense of your weight, the way your flesh occupies momentary space, the fullness of it beneath my palms. If I could attach our blood vessels so we could become each other I would. If I could attach our blood vessels in order to anchor you to the earth to this present time I would. If I could open up your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours I would. It makes me weep to feel the history of you of your flesh beneath my hands at a time of so much loss. It makes me weep to feel the movement of your flesh beneath palms as you twist and turn over to one side to create a series of gestures to reach up around my neck to draw me nearer. All these moments will be lost like tears in the rain.36

7 Miles a Second. © 2013 David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook.

Aside from two arms flung outward by the force of the interpenetration, the only object that retains its integrity is David’s head with its impassive expression, closed eyes, and presentation in strict profile—like an antique or Renaissance commemorative relief, announcing the presence of the already dead. But that dominant central image is glossed by the juxtaposition and superimposition of several smaller panels, which provide a resonant and elegiac context. Especially poignant to me is the juxtaposition of two hands in the upper left: one that of a dying patient, the other that of David. The latter is fleshy yet passive in life, the former gray and grasping in death. Into the wrist of the dying man slides a transfusion needle, and we see the blood, not David’s blood, but the blood of an anonymous other, flowing through a thin tube that effectively short-circuits the writer’s desire to anchor his lover by “attach[ing] our blood vessels so we could become each other.”37

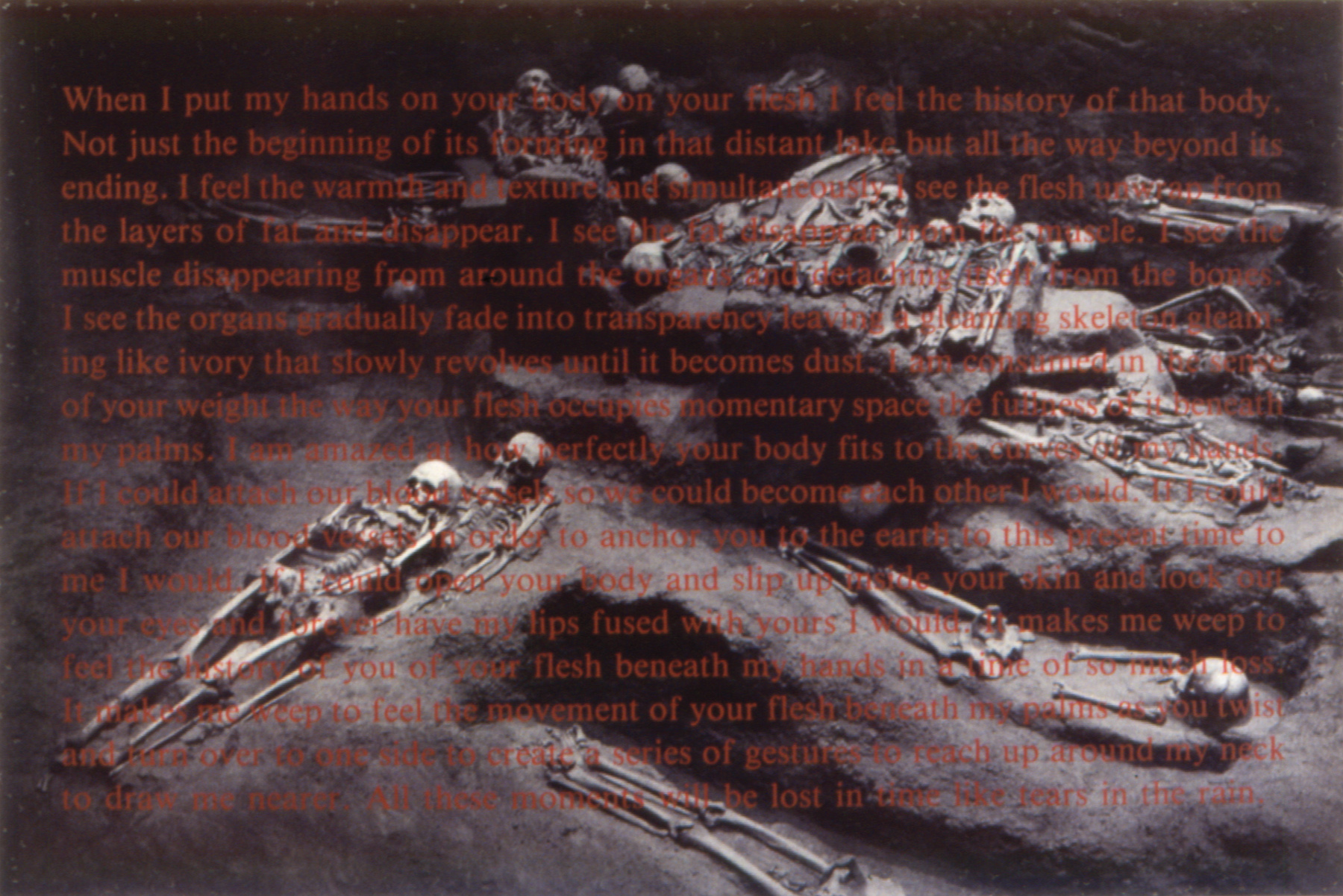

David Wojnarowicz, When I put my hands on your body, 1990. Silkscreen on silver print, 34 × 46 inches. Courtesy of The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

It’s hard (maybe impossible) to know whether this two-page spread was completed, or even roughed out, before Wojnarowicz’s death in 1992. However, we do know that the artist used the same text in a quite different photographic elegy dated 1990.38 In that work, we look down into an archaeological excavation at a group of skeletons laid out on various levels within an expansive pit. Some are complete, some fragmentary, some placed side by side, some alone or arranged chaotically.39 Rather than being a couple, they are a virtual community, brought together across time in death, their skeletons like gleaming ivory not yet revolved into dust. In the left foreground lies a couple close together. It seems that they must be the particular pair to whom the text overlaid in silk-screened red applies. And like, but so unlike, the exploding lovers in the Romberger/Van Cook version, they also testify to the impossibility of desire’s realization, at least that final desire for a transcendent union beyond or despite death. Instead, they lie side-by-side in the dust of time (calling up the echo of the “dry bones” evoked by Eliot and Ezekiel), a dust that will eventually absorb both the tears and the rain that fall together.40

Glenn Harcourt has a PhD in art history from the University of California, Berkeley. He lives and works in Pasadena.