Schoolchildren are taught that World War I had something to do with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. The vagueness of that “something” is significant, for as older schoolchildren know, the assassination set in motion a series of diplomatic commitments that produced, within one month, the invasion of Serbia, within three months, the Western Front, and within six months, a global engagement between the Allies and the Central Powers. The Great War was thus a war predicated on covenants, and the enforcement thereof. Wars are easy to fight when the enemy is at the door, raping the missus and murdering the kids. But wars fought based on contractual obligations are hard to recruit for. Enter the imaginary—image as rhetoric versus image as iconography.

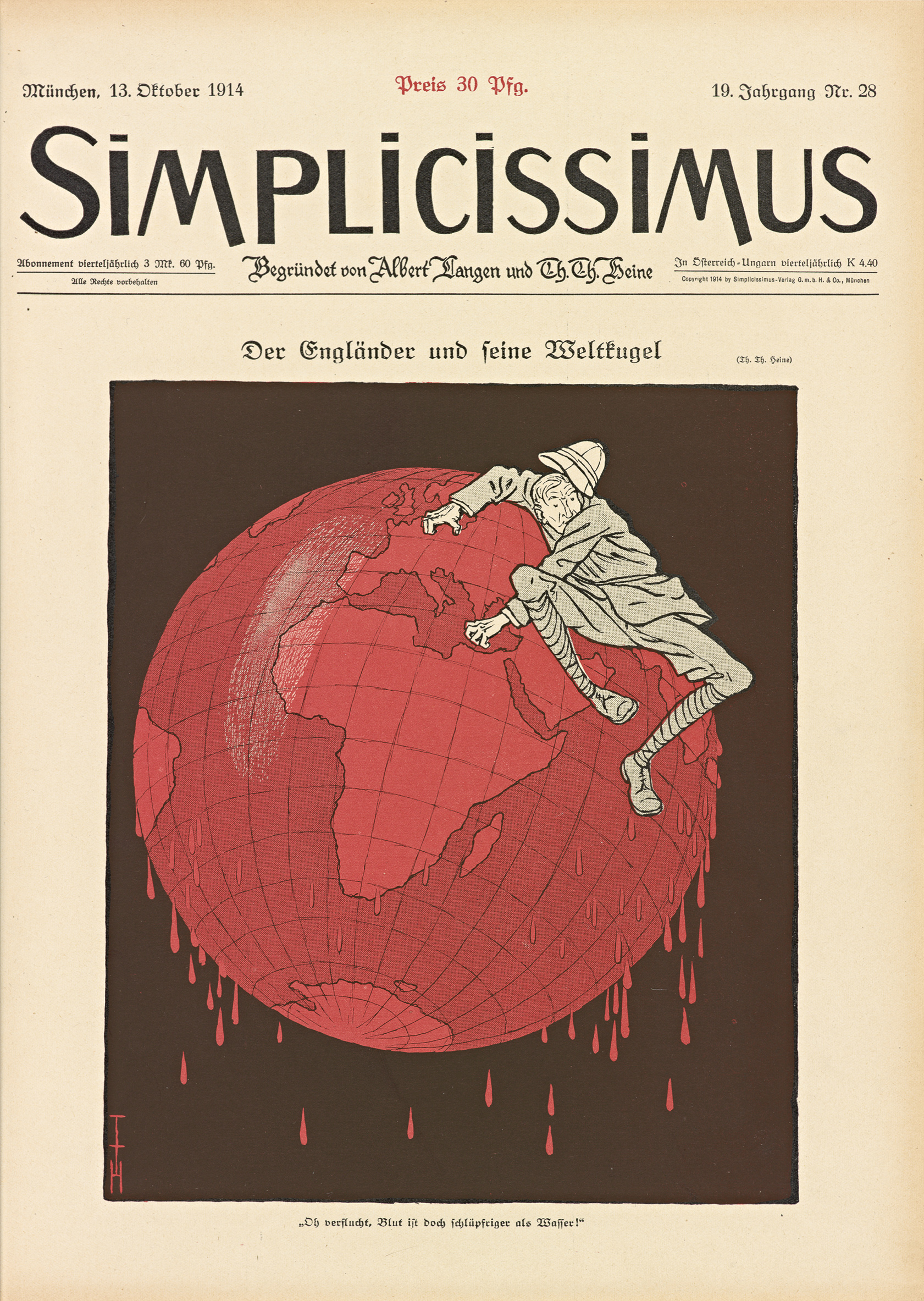

The Getty Research Institute’s exhibition, World War I: War of Images, Images of War takes as its premise that there is a working distinction between the propagandistic image and the more self-reflective work of art. The first is driven by patriotic promotional campaigns, the need to communicate to, the second by the artist’s internal reaction to the realities of war, the need to communicate into. Prose versus poetry, polemic versus aesthetic. By following the arc of the war’s rhetoric, the exhibition follows the arc of the war’s imaginary, from the caricatures in the German satirical journal Simplicissimus and the French journal Le Mot at the beginning of the war to the caricatures of George Grosz and Otto Dix at its terminus. That the first are provincially considered “image” and the latter “art” is one of the legacies of the Great War. For, as the show reveals, this divide is an ecclesiastical1 conceit, based in faith, not fact.

Thomas Theodor Heine, The Englishman and His Globe, cover of Simplicissimus 19, no. 28 (October 13, 1914). 15 3/16 × 11 5/16 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (85-S1389). © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Carlo Carrà, Futurist Synthesis of the War, 1914. 11 3/8 × 18 3/16 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (93-B20974). © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome.

To this segregate end, the GRI’s main exhibition room has been thematically split in two. The section “War of Images” begins with the introductory subsection “Into Battle!” then moves down into a larger room devoted to the “War of Cultures” as waged by the major players. The “War of Cultures” features public posters and periodicals, and the development of what could be called ethnic aesthetics, a visual shorthand for the various participants, often based on the détournement of national symbols and the debasement of “racial” types. Germans drew a Russian bear bleeding a snowy retreat after the 1914 battle of Lodz, and metamorphosed His Majesty’s noble lion into a floppy sea lion, impaling its flippers on the points of a crescent, symbol of the Ottoman Empire. The Allies put Prussian helmets on feral pigs, and the Italian Futurist pamphlet, Futurist Synthesis of the War (F. T. Marinetti and Carlo Carrà, 1914) mixed manifesto and parole in libertà2 so that the positive attributes of the Allies (French intelligence, English pragmatism, Russian solidarity, Italian genius) drives a penetrating wedge into the negative traits of the Central Powers (German brutality, Austrian stupidity, “Turchia = 0”), nutshelled with a quite Modern binary: FUTURISMO > Passatismo (FUTURISM > Traditionalism).

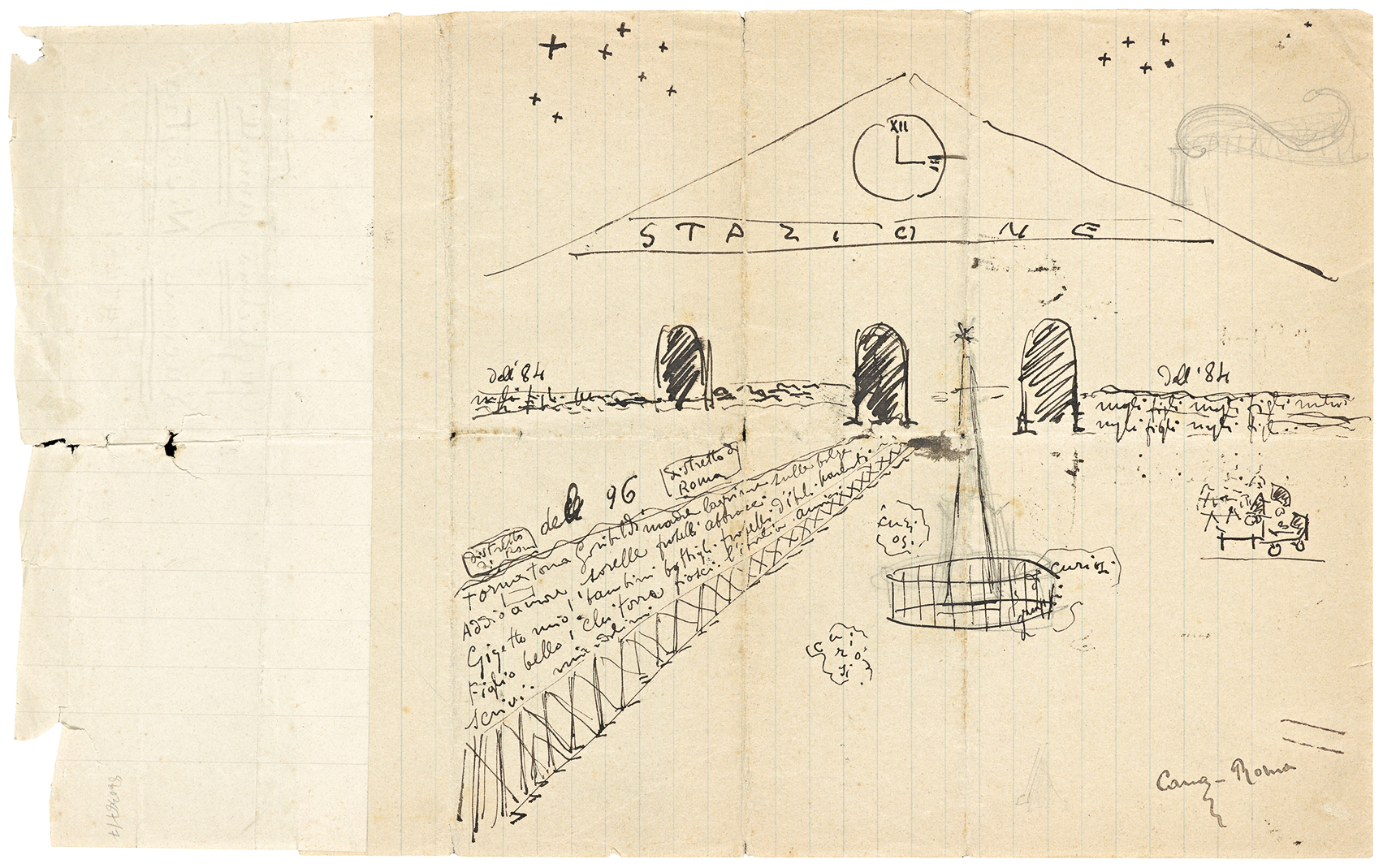

Francesco Canguillo, Train Station, ca. May 1915. Ink and pencil on paper, 8 3/16 × 13 3/16 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (860387) © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (detail), from Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Sketchbooks, 1917–32. Pencil, ink, and watercolor on cigarette box. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (850463).

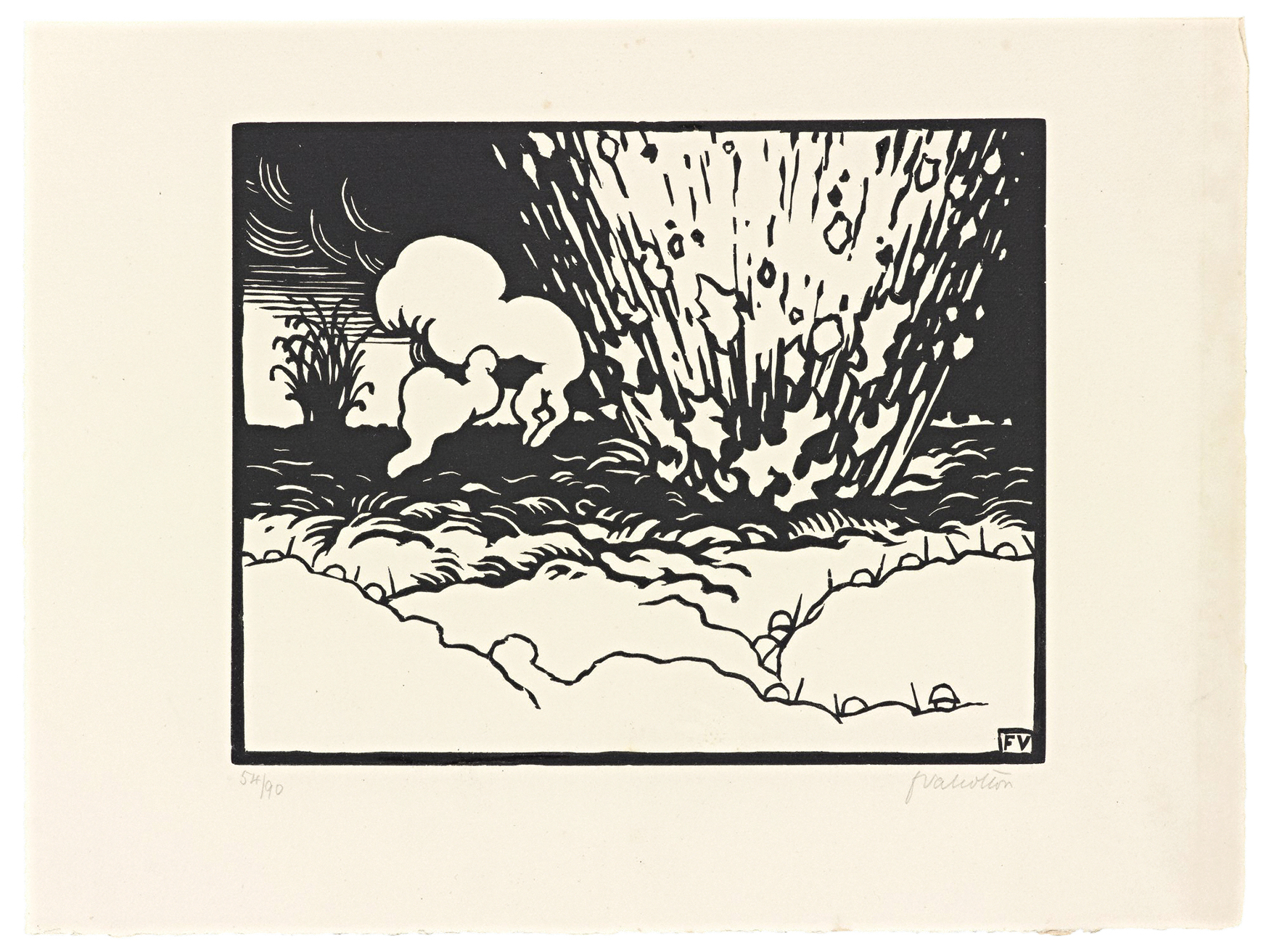

The second section, “Images of War,” is more experiential, containing formal and informal renderings of the war as lived from varying distances. A series of bold lithographs by Russian avant-gardist Natalia Goncharova (Misticheskie obrazy volny: 14 litografti [Mystical images of war: 14 lithographs], 1914) combine religious and militaristic images (Angels and Airplanes, 1914). Etchings and woodcuts by assorted artists such as Félix Vallotton (Swiss), Henry de Groux (Belgian), Frans Masereel (Belgian), Max Unold (German), and an illustrator, Richard Seewald (German), follow German artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Album of Apocalypse Drawings (1917), an exquisite series of miniature watercolors painted on the backs of cigarette packs. Done while Kirchner was confined in a sanatorium for a nervous breakdown prompted by his brief non-combat military experience, the watercolors, unlike Goncharova’s lithograph or Valloton’s crayon, only allude to war—the apocalypse is what happens after.3 A number of pieces by Marinetti, including his great parole in libertà work, After the Marne, Joffre Visited the Front by Car (1915), are displayed with Umberto Boccioni’s 1915 war diary, drawings by Augustin Grass-Mick (France), a series of delicate picture medallions by Berthold Loeffler (Austria), and Train Station (1915), a spectacularly haunting Futurist drawing by Francesco Canguillo (Italian), in which the bodies of young men going off to war are composed of their words of farewell to friends and family. The middle of the room holds a vitrine of trench art, made by combatants from battlefield detritus: a letter opener fashioned from bullets and scrap metal, inscribed “Ypres 1916”; symbolically painted helmets; a 1910 canteen carved in memory of Russian POWs; a French mortar shell illustrated with a scene of hand-to-hand combat; and an Iron Cross-marked landscape painted on a cow’s shoulder bone.

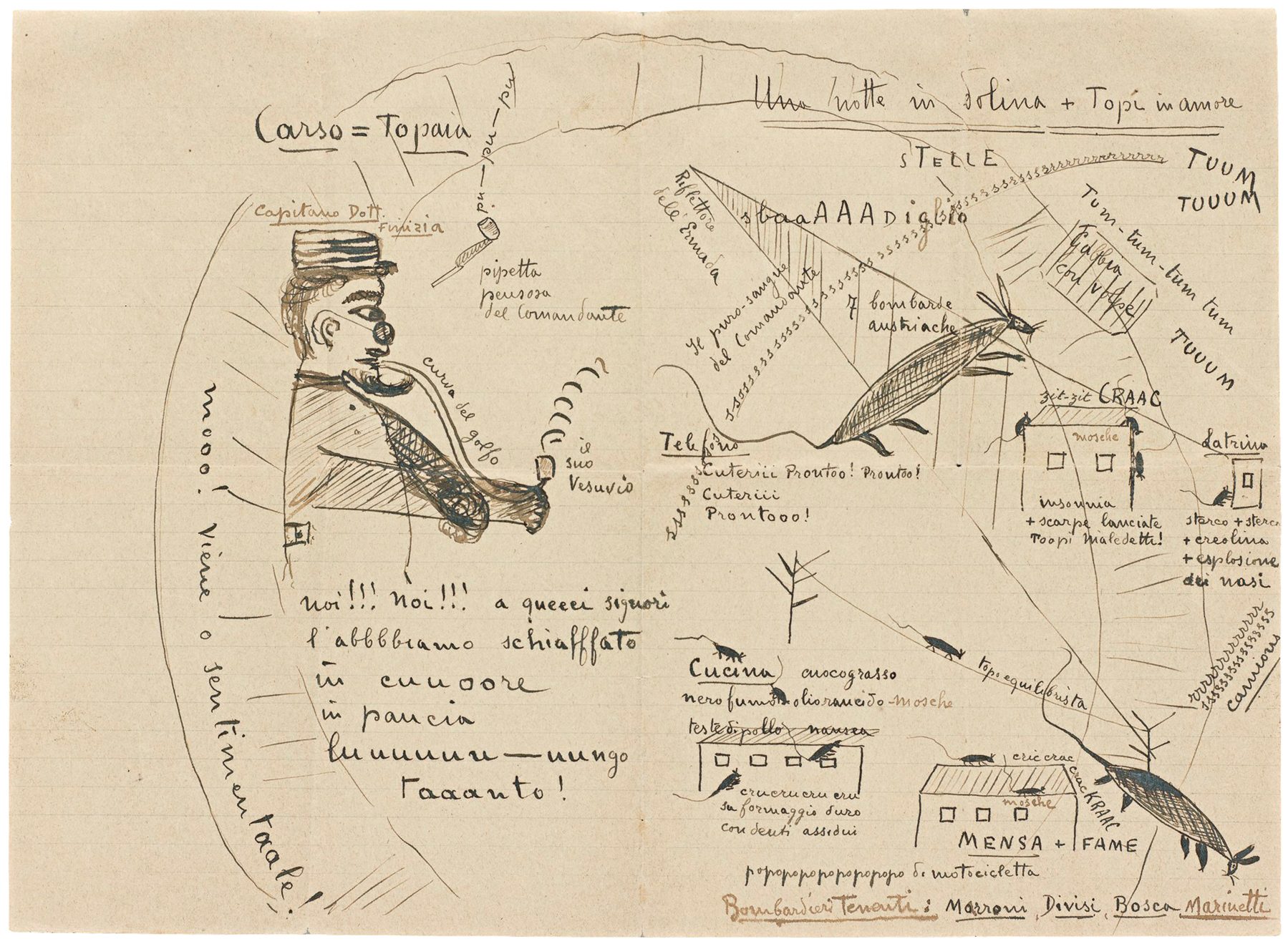

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, The Carso = A Rat’s Nest: A Night in a Sinkhole + Mice in Love, ca. 1917. Pen and ink on lined paper, 10 5/8 × 14 5/8 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (870379). © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome.

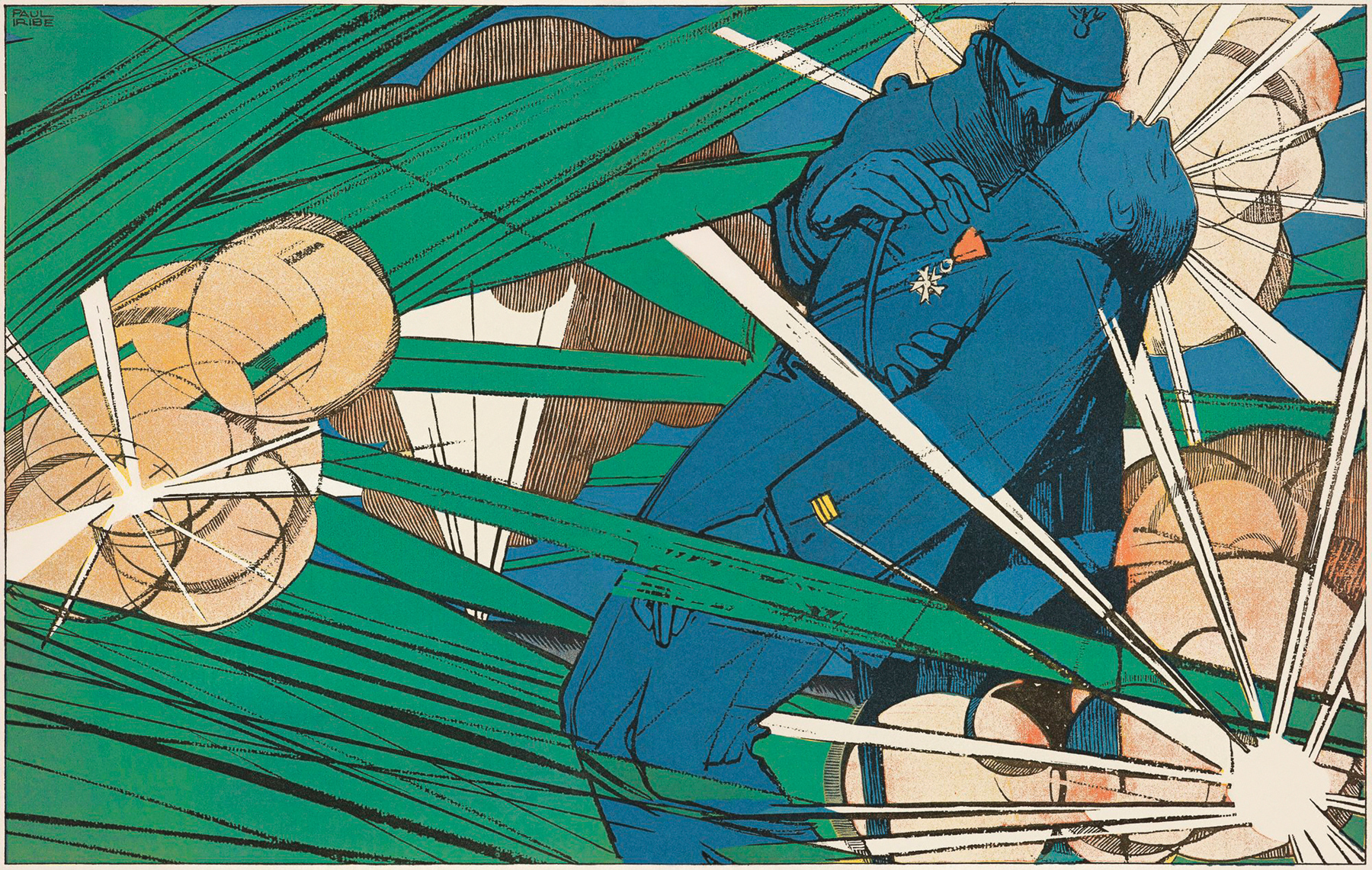

Paul Iribe, After the Execution, cover of Le Mot 1, no. 5 (January 9, 1915). Color woodcut, 17 3/8 x 11 3/16 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (84-S761).

Finally, “Aftermath” lies appropriately apart, in the original GRI gallery, a ramp and lobby away from the main exhibition space. This section is smartly divided into triumph and trauma, featuring patriotic periodical illustrations (e.g., “Your Turn, Germany!” from Le Petit Journal, France, 1919), a video room with excerpts of war films (Stosstrupp 1917, Germany, 1934; J’accuse, France, 1919; The Big Parade, United States, 1925, and The Lost Battalion, United States, 1919),4 the necessarily included work of George Grosz, Otto Dix, and Käthe Kollwitz, and lesser known pieces by Fernand Léger, such as pages from his small book, J’ai tué (I’ve killed, 1918).5 The final exhibition image is Nach Zwanzig Jahren: Väter und Sohne 1924 (Twenty Years Later! 1934), a sepia-toned photomontage by German Dadaist John Heartfield6 in which an antique General von Hindenburg oversees a uniformed army of children on the march as adult skeletons stand at rank attention. The “Aftermath” section also contains audio clips of veterans’ calmly horrific recollections. While these recordings serve an obvious historical purpose, it should be noted that sound plays its own part in the exhibition. Among other commendable curatorial touches, there is an excellent recording of Luciano Chessa performing Marinetti’s parole works, The Carso = A Rat’s Nest: A Night in the Sinkhole + Mice in Love (1917) and In the Evening, Lying in Her Bed, She Rereads the Letter from Her Artilleryman at the Front (1917). This, together with the translation of the Mayakovski-Malevich postcards into English comic verse, sonically underscores the Futurist works as works of sight and sound. This emphasis is significant, as sound was one of the inescapable senses of the war: in addition to the screams and whistles of the battlefield, the booms of Big Bertha crossed the Channel, punctuating polite Hyde Park conversation. Smells were local, but sound carried.

As the exhibition demonstrates, by 1914, images were already understood as profoundly ambivalent. The image’s unique ability to convey a great truth necessarily included a capacity for great deceit. Exhibition wall text states that the use of images was considered slanderous by the terms of the 1907 Hague Convention. More precisely, Article 22 of the Hague Convention of 1907 provided, “The right of belligerents to adopt means of injuring the enemy is not unlimited.” The German army interpreted this clause to proscribe not merely dropping propaganda pamphlets on the locals, but generation of any propagandistic imagery that might “interfere with an enemy’s self-determination by agitating its population or its army against the sovereign power.”7 While the Germans busily valorized the German cause and satirized the enemy as feeble (The Englishman in Hell, Thomas Theodor Heine, 1915) or otherwise effeminate (The Proud Marianne, Olaf Gulbransson, 1915), the enemy more successfully portrayed the Germans as bloodthirsty, marauding brutes (German Atrocities, Eugène Damblans, French, 1917; Destroy the Brute, Henry R. Hopps, USA, 1917), assisted by the Germans themselves in the campaign not inaccurately known as “The Rape of Belgium.” Throughout, agitation of one’s own population was fair play, and representational images of Our Heroic Soldier (For the Fatherland Died Infantryman Ludwig Hennes: Honor His Memory. An Example and Model to His Successors, Fritz Erler, German, 1917) were studiously opposed to cartoons of The Other Guy (The Dream, Henri Zislin, 1916). These cartoons were just as representational, not only in their highly figural properties, but also as they drew heavily upon the development of race theory. If the German-idealized German was square of jaw and broad of shoulder, the Allied-racialized German was a sausage-fingered, thick-lipped brute that was genetically incapable of human civility, let alone great culture.

Eugène Damblans, The Sower of False News, cover of Le Petit Journal: Supplément illustré 26, no. 1265 (March 21, 1915). 17 7/16 × 12 5/16 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (84-S404).

As amply proved by the exhibitions’ documents, the Euro-Russian “War of Culture” was not just a politicized fight between French and Germans, or Russians and Turks, but was also a race war. Nineteenth century scientific racism met twentieth century nationalism to argue that state borders should mirror national racial groups. Aesthetics, pace Kant, was taxonomically enlisted. Thus the official German devotion to a strictly representational aesthetic was countered with an Impressionistic practice that was no less pro-German: the March 17, 1915, cover of the weekly Kriegszeit Kunstlerflugblätter was a Max Liebermann lithograph of Immanuel Kant; the January 20, 1915, cover was Erich Büttner’s lithograph, Portrait of Hindenburg, with a plauditory quote by Goethe. In France, the David-inspired Empire aesthetic of Le Petit Journal was met with a streamlined “classical” modernism championed by Paul Iribe and Jean Cocteau’s 1914 journal, Le Mot, “a pure French return to sublime simplicity.”8 And this is where the binary between art and image, as reflected in the structure and infrastructure of the exhibition,9 dissolves. A dissolution that remains irresolute. For despite our belief that we are properly skeptical of image (though arguably less so of art), and our self-consciousness about the proposition that art is always context dependent, we maintain a working distinction between the two. And it is this maintenance that has become the primary work of contemporary art history.10 War of Images, Images of War suggests, if not the why and how of this current state of affairs, at least the beginning of a historical hypothesis.

Proposition 2 of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s 1921 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus states that “the existence of states of affairs” is what is considered a “fact.”11 Keep in mind that “fact” as “state of affairs” should not be confused with “fact” as “truth.” For Wittgenstein, who developed his Tractatus as an Austrian soldier and prisoner of war in World War I,12 the “state of affairs” was simply what was known (or knowable) about the world.13 Thus, a fact is what is believed. According to Proposition 3, “The logical picture of the facts is the thought.”14 Thought, then, is fact perceived logically. Thought as the combination of fact and logic provides the key to both Wittgenstein’s philosophy and the image/art divide. The first principle of logic is the tautology: A = A. This was Aristotle’s law of identity, from which we can move to considerations of difference (A ≠ B) and equivalency (A ≅ B). An image, in its simplest form, is a tautology, the representation of the state of affairs that it is a representation of. If the image appears to us to be a proper representation (unadulterated, makes contextual sense, etc.), it is a thought (A1 = B1). But thoughts are linguistic (“apple”) and facts are not. To this end, the Tractatus proposed a picture theory of language: language = “apple” + [insert image of apple]. Proposition 2.1 states, “We make to ourselves pictures of facts,” and Proposition 2.141, “The picture is a fact.”15 That is, the picture is the representation of the current state of affairs that we make to make the world around us. The tableau vivant (P = A1 ≅ B1).

I bring in Wittgenstein for three reasons. First, as noted, because the Zeitgeist that prompted his philosophical parsing of the world into logico-lingual pictures and states of affairs into facts and thoughts was born of the First World’s first world war. It should go without saying that World War I was famously chaotic, fabulously absurd: from the great muddy standstills of trench warfare to the endless mowing of men running towards machine guns, from tales of trench rats who ate the cats that Nature and man sent to eat them, to battlefield corpses who stuck around, rotting and grinning, unable to be buried in the too-literal No Man’s Land, to the jibbering of the shell-shocked and the surreal mugs of the gueules cassées, the Great War seemed—was—sans raison. A cleansing logic would be wanted.

Second, Wittgenstein’s insistence on what we might consider the literality of the image corresponds with the Moderns’ desire to segregate what they considered “image” (pure representation) from stodgy academic “Art,” fusing direct “image” (art) with “life.” According to Ezra Pound, as inspired by F. T. Marinetti, “image” was a textual truth outside the muck of metaphysics.16 Russian and Italian Futurists argued that life as such could and should be art per se and vice versa. The fusion of text and image, image and art, art and life, or what occurs by way of illustration (metaphor) and by way of image (metonymy), was hallmark and rallying cry of the artist/imagist by the war’s beginning. It is significant then that, after the war, Western European art retreated into its medium specificity, and Russian art became subsumed with the project of the Soviet. So the question ultimately posed by and plaguing War of Images, Images of War lies in the attempted segregation between what is tendered as illustration and what is preserved as art. Because there is no difference, and there was no difference.

Félix Vallotton, The Trench, from C’est la guerre! (1915–16), plate 1. Woodcut, 9 7/8 × 13 3/16 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.PR.1). Gift of Dr. & Mrs. Richard A. Simms.

Natalia Goncharova, Angels and Airplanes, from Misticheskie obrazy voiny: 14 lithografi (Mystical Images of War: 14 Lithographs), plate 10, 1914. Lithograph, 12 7/8 × 9 7/16 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (88-B28354). © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

The conceit of the Getty’s exhibition, that there is an image/art divide between “War of Images” and “Images of War,”17 comports with, and confounds, the Modernist penchant for binarisms18 that was knowingly confused by Modernist practices themselves. It is clear throughout the show that neither medium nor message separated image from art at the time: artists worked with the same materials and with an eye toward the same masses as illustrators. Cocteau’s Le Mot is image as art, art as image. Malevich and Mayakovski’s postcards and poems were propaganda as art, art as propaganda.19 Artist Vallotton worked in cartoons, as did illustrator Heine. Simplicissimus, like Marinetti, drew in parole. Given Goncharova’s statement, “I assert that religious art—and art that exalts the state—was and will always be the most majestic, and this is because such art, first and foremost, is not theoretical, but traditional,” is the message in her 1914 Angels and Airplanes one of pacifism, militarism, or iconic equivalence?20

For, third and finally, the understanding that we believe what we see and see what we believe is the problem animating Wittgenstein’s philosophy and the contemporary distinctions made between what is “image” and what is “art.” The relationship of “image” to “art” is a Wittgensteinian argument about facts and thoughts, about states of affairs and sensible21 propositions. And while we may speculate facts outside our thinking and entertain ourselves with thoughts outside our facts, the two remain semantically, and aesthetically, conjoined.

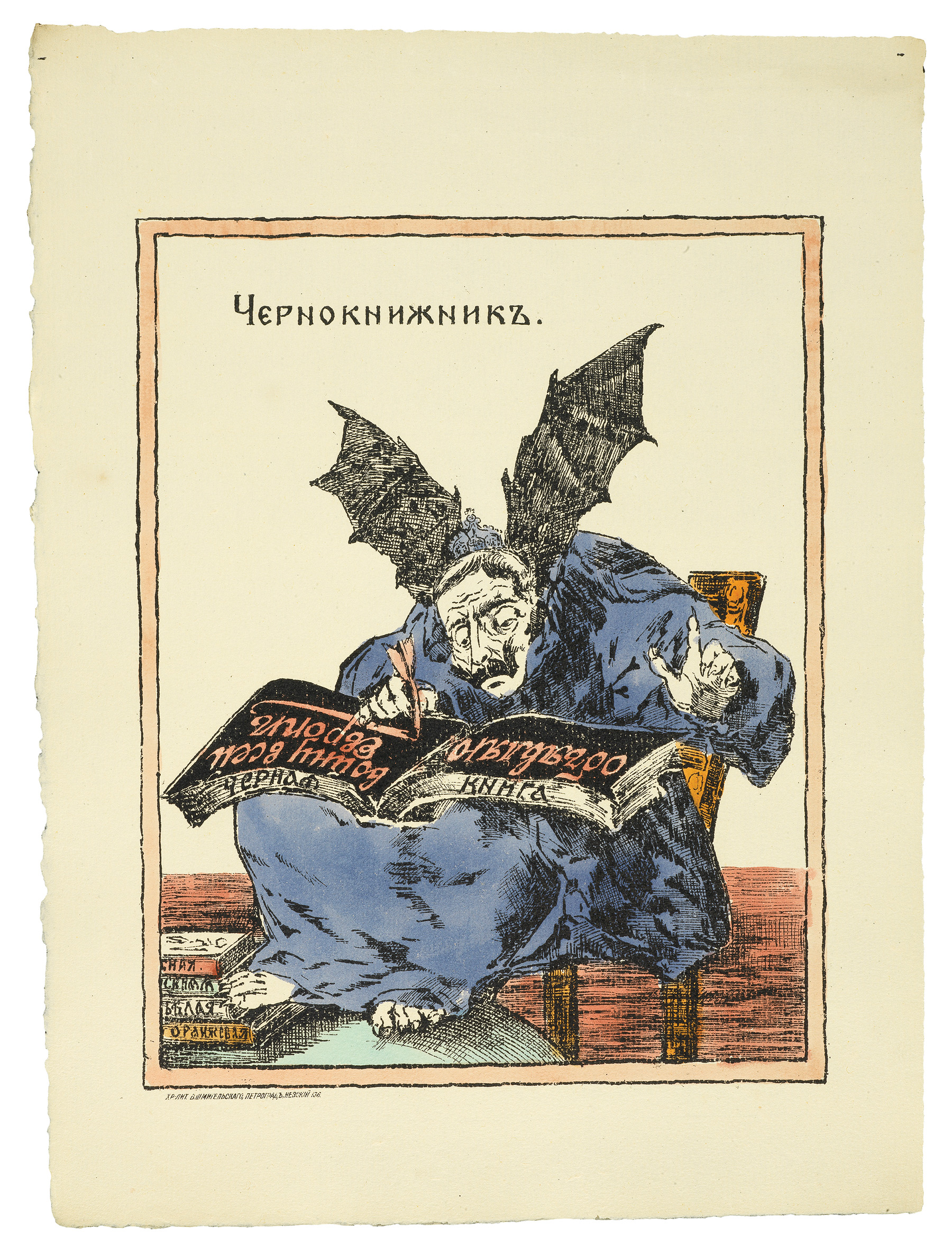

Black-Booker, from Kartinki—voina russkikh s nemtsami (Pictures: The Russian War with the Germans), plate 31, 1914. Hand-colored lithograph, 12 11/16 × 9 1⁄4 inches. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (92-F293).

If the point of contemporary art is that the object (however loosely defined) is no longer the point of art but simply the platform for art, the image/art distinction is predicated on that platforming. To put it another way, we apply aesthetic theory and history to aesthetic subjects, like the artist’s cellphone video, but not to non-aesthetic subjects, for example, the cellphone video of Eric Garner’s killing. Indeed, David Joselit’s February 2015 Artforum article on the failure of the Garner video to convince a grand jury to indict the officers involved reaches past the video itself to a certifiably aesthetic performance by Pope.L in which the artist eats and regurgitates the Wall Street Journal. In addition to maintaining the divide between image (Garner video) and art (Pope.L performance), Joselit assumes that the former should, in some forensic sense, “speak for itself” whereas the latter requires a textual exegesis, in this case, a limited-edition book, Eat Notes, published “in conjunction” with the performance, Eating the Wall Street Journal.22

Similarly, contributors to the September 2014 “Art vs. Image / Bild vs. Kunst” issue of Texte Zur Kunst stressed, in various ways, the role of language or sign in order to forge a working critical distinction between the two. Citing W. T. Mitchell’s thesis that “an image is the sign that pretends not to be a sign, masquerading as (or, for the believer, actually achieving) natural immediacy and presence,” Gertrud Koch notes that the contemporary notion of image has become “coeval” to language, having both a symbolic and affective relationship to the world as such; art finds itself assigned the (leftover) task of a scientific study of affect.23 Peter Osborne links image to language in a Derridean swoop: “Image is an ideological concept.” Refuting Mitchell, Osborne sees the image as a Kantian mediation between aesthetic and logic, “a relationship between a materially embedded virtuality and an infinite multiplicity of possible visualizations.”24 The post-Conceptual/postmodern language-image dialectic has been makeweight since Jean-Luc Nancy’s 2003 book, The Ground of the Image (“image shows itself to text, which shows itself to image”25), which insisted on the material “presence” of the image,26 as well as the link between image and violence, given that violence must make an image of itself that “passes out ahead of itself and authorizes itself.”27 According to Nancy, art, by way of contrast, “marks the distinctive traits of the absenting of truth, by which it is the truth absolutely.”28 So the job of art is to upset the apple cart. The problem is that art is image. Even when it’s not.

Paul Iribe, “I Have You My Captain. You Won’t Fall.” (detail), from À coups de baïonnette 9 (June 1917), pp. 424–25. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (93-S507).

To put it reductively and comprehensively: I see image, I see art. To borrow from another ideological/teleological frame for a moment, medieval theories of optics revolved around classical theories of intromission and extramission. Intromission held that an object transmitted its visible form to a subject. The viewer was passive. Extramission posited an active viewer who emitted the power of visuality as an optic beam, enabling the apprehension of the object. In either case, there was an understood relationship between object-matter and immaterial representation: Plato’s theory of vision, dominant during the early Middle Ages, posited “seeing” as produced by a beam of light coming from the eye meeting a force generated by the object. Augustine believed this beam was akin to, though separate from, the soul, and differentiated between corporeal, spiritual, and intellectual modes of vision. Corporeal was the lowest as most dependent on sheer physical materiality. Boethius emphasized that intellectual vision was illuminated by the divine, and it was generally agreed that spiritual vision was the highest form, consisting of the ecstatic glimpse of divine light produced by contemplating the Creator in the trinity within (memory, understanding, and will), dependent on nothing but the encounter with the Absolute.29 When the Getty wall text reads: “The war of images ultimately clashed with images of war,” the distinction between image as propaganda and art as image—like the contemporary debate over Image versus Art—becomes another argument about extramission and intromission. “Image” is lit from within, transmitting its messages to all comers; “Art” requires the individual beam of light, the greater understanding, supplied by the better viewer.

For Wittgenstein, every fact had one mirror-image sharing the same logical form as that fact. This logical picture Bild was distinguished from the spatial picture Kunst, the province of ethics and aesthetics, that which cannot be said. For that which cannot be said may only be shown: there is no fact-image, just the frame of the mirror. In other words, art does not share the same logical form as fact. Or, to put it in contemporary art terms, Art does not share the same logical form as Image.

In this, the Getty exhibition’s segregation of the war’s aftermath reflects the psychic split, not only between winners and losers, living and dead, but also between our consideration of what is art and what is image. Images of War, War of Images asks us to think about Grosz’s cartoons as art and Heine’s cartoons as image because the Heine cartoon occupies the position of logical picture, of “fact” or known “state of affairs,” whereas the Grosz cartoon is put in the position of spatial picture, of “non-fact,” or the unknowable. The known is a matter of content; the unknowable is a matter of process. Or, as criminal lawyers put it, it’s not whether it’s true—it’s whether it’s believable. For all that matters, Wittgenstein himself reflects a fact about the world in which an Austrian philosopher and secular Jew, exposed to the regimented chaos of war, developed a structural theory of meaning as language construct, always context dependent and already limited by our sense of the world. For the first Proposition is: “The world is everything that is the case.”30 A case is tried in courtrooms; a case is that which can be argued based on believable assertions about the world as already understood. Proposition 6.522: “There is indeed the inexpressible. This shows itself; it is the mystical.”31 Art is thus non-sense: it exists at the world’s end, at the limit of understanding, which was, then, and apparently is now, mystical and manifest.

Today we read our images textually and our texts imagistically—scan first, read later, a phone “text” having all the presence, immediacy and sign-effacement as a snapshot, which has become a Snapchat—and there is no logical distinction between art and image. Because there is the logical picture of art, the “fact” of art, which currently lies and belies in images. Or, in the aphoristic and Wittgensteinian words of many dictionaries, “semantic change, semantic confusion.” For the real final piece suggested by World War I: War of Images, Images of War is found round the corner from the show’s “Aftermath,” in the men’s room. Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) was a logical picture of a spatial picture: the non-sense of sense, the sense of non-sense. A model of excrescence that is the very image of art and the art of image. Art may have won the battle but images took the war.32

Vanessa Place is an artist, writer, and criminal defense attorney.