In 1896, King Ubu, the bourgeois buffoon dreamt up by playwright Alfred Jarry, declared, “We shall not have succeeded in demolishing everything unless we demolish the ruins as well.”1 If “demolishing everything” qualifies as success, then the self-styled Islamic State (ISIS) has an excellent track record. ISIS’s brutal enforcement of a puritanical interpretation of Islam, expanding since mid-2014 and decried by most Islamic organizations, makes extensive use of social media and Internet dissemination of propaganda videos to simultaneously incite world outrage and invite supporters to its virulently anti-modern and anti-Western “utopic” project.2 In the midst of numerous videos of beheadings and mass murders, perhaps most incomprehensible to many audiences has been the video of seemingly spurious destruction of archaeological heritage. Yet it is precisely the superfluity of such acts that gives these videos the potency to address sympathizers and detractors. Unlike most of ISIS’s other targeted demolition of cultural heritage—including the destruction of numerous Islamic shrines and Christian churches currently in use, as well as libraries containing unique historical manuscripts which, in historicizing Islam, could undermine ISIS’s a-historicist rendition—the destruction of objects in closed museums, which nobody worships or visits, seems to serve no immediate purpose. Yet the distinction between Western relative indifference to the destruction of local cultural heritage under ISIS and the video of the destruction of the Mosul Museum, which raised an immediate furor as institutions such as UNESCO labeled the act as “terrorism,” “war crimes,” and “cultural cleansing,” underscores the power of this apparently useless violence. What made this event so distinct from the panoply of largely unmentioned destruction long underway in Syria and Iraq as to evoke responses resonant with those to beheadings? What can these responses tell us about the functions of art, archaeology, and museums in contemporary global culture?

ISIS destroys Statues in Mosul Museum, YouTube video, published April 7, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KELYkEk1gU, accessed May 5, 2015.

As opposed to the similarly distributed videos of violence against people, which serve to terrorize and subdue conquered populations and threaten enemies, these videos of destroyed cultural artifacts depend on values attributed to the objects under attack through sign systems rooted in the idea of art. They thus attack a hegemonic value system extending far beyond the borders of the Islamic State or simple terrorism. They signify a conflict between the values of Western civilization and national identity—both of which have been affiliated with archaeology since the nineteenth century—and the dissolution of these grand narratives in the twenty-first. Although the immediate questions raised by ISIS’s destruction of heritage may be the pragmatics of preservation, in the long term we must ask, whose values are represented in these objects, in museums, and in archaeological sites, and to what end? As we build systems of defense responding to such challenges to the dominance of these ideologies of value, does the existing system of historical narrative, established with the birth of archaeology, remain the most appropriate system of valuation in our current global and cultural climates? Or can we resist terrorism by reflecting on destruction as an opportunity to engage future values for archaeological artifacts that respond to the complexities of identity politics, postcolonial violence, and cultural diversity?

If the purpose of terrorism is to terrorize, then perhaps the best defense is laughter. For example, an Egyptian wedding was celebrated by mimicking the burning cage in which ISIS executed a captured Jordanian pilot.3 Some online magazines recognized the artistic potential in the destruction of the Mosul Museum. “The Islamic State wins prestigious Turner Prize for Modern Art,” declared The Pan-Arabia Enquirer; “ISIS to Exhibit Floating Pavilion of Art Destruction at Venice Biennale,” declared Hyperallergic on April Fools Day.4 After all, if modern art conceived of itself as a perpetually renewing avant-garde struggle to undermine the hegemonic order represented in artistic tradition, what could be a more liberating gesture than the destruction of a heritage that has become an idol? We can consider the object an idol because the response to its destruction has been as great as that to human life, even though most of us would be hard-pressed to explain exactly how to apprehend these artifacts of the past. Heritage becomes an idol at the moment when we value it for the fact of its being declared heritage but no longer maintain a dynamic relationship with it. Seen in this light, the video of the destruction of the Mosul Museum inadvertently enters the perceptual realm of anti-art, because “the idea of [art’s] abolition does it homage by honoring its claim to truth.”5 After all, archaeology itself gained much of its modern resonance through its incorporation into discourses of art. What then might also be gained by thinking of archaeological destruction through contemporary resonances of the same discourse? By labeling the video only as “terror,” we close our minds to the exclusions evoked by contemporary narratives of heritage that render it effective as propaganda. Viewing the video instead, against the grain, as art, resists the terrorist’s intention to induce fear. Treating the “work” of ISIS as a Duchampian readymade engages it in an expressive mindset dependent on the viewer rather than the maker. Although we are tragically hard-pressed to save what ISIS is destroying, human and historical, reclaiming their acts as motivation for cultural production mitigates their success in the erasure of cultural memory. It encourages us to listen to the subaltern silences articulated in the positive reception of propagandistic destruction.6

Sinem Dişli, Dissemblance: Babel, 2015. Stills from multi-screen digital video loop. Courtesy the artist.

These suppressed silences emerge through interplay of destruction and restitution inherent in archaeology, and continue through the narratives attributed to them in museums. As King Ubu continues, “But the only way I can see of doing that is to use them to put up a lot of fine, well-designed buildings.”7 Understanding the museum as a beautiful display of destroyed ruins, we begin to unravel the ideology of archaeology as a purely positive practice that uproots ruins from their state of nature in order to bring them into a predetermined narrative of culture. Rather, the innocence of archaeology depends on recognizing local culture as nature, as a resource to be mined and given form. Acquired by Magnum in 1964, Ara Güler’s 1958 photographs recorded the intimate relationship between the villagers of Geyre with the antiquities of their home immediately before the expropriation of the village, excavation of the site, and its transformation into the open-air museum of Aphrodesias.8 The displaced village lost its organic relationship with antiquities through the site’s transformation into a museum. Similarly, when Sinem Dis ̧li charts local villagers near her native city of Urfa walking up and down a mound they call “mountain,” she articulates a local relationship with the landscape ripe for destruction if archaeology recoups the site.9 This establishes a hierarchy of worth where fine, well-designed museums tell societies stories of themselves even as they invite people to forget their own relationships with objects not as history, but as inextricable parts of daily life.10

Ara Güler, Village Mosque, Geyre, with Column from Nearby Site of Aphrodesia, 1964. © Ara Güler/Magnum Photos.

The transformation of artifacts from the mundane landscape of distant villages into archaeological heritage depends on their redefinition as signs for hegemonic narratives including civilization and nation. Capitalizing on the universalism of Enlightenment humanism and relying on the powerful fiction of the history of civilization as established through Hegelian historiography, these narratives submerge local values within broader systems of power.11 The destruction of the Mosul Museum gains its resonance through the tension invested in these systems. In contrast to the violence against individuals or populations, or the destruction of active spaces of worship, it operates as pure symbolism. It distinguishes between the cultural capital invested in the museum and those who, through resistance or lack of access, understand such cultural capital as a sign of their oppression. The figures in Patrick Chappatte’s cartoon Mosul Museum Devastated (2015) take pleasure in the museum as a site of liberation through destruction because they do not respect a museum, partly because they have never been there before. We can understand this as a local effect resulting from the dissolution of the educational systems through which Iraqis were once inculcated into nationalism through archaeology since the 1990s.12 But we can also understand this in the context of far broader social exclusions, in which the working classes (and among them most immigrants) in Western societies often lack access to dominant forms of cultural capital. The figures in the cartoon may be local but, like many adherents to ISIS, they may also come from the broad ranks of the global disenfranchised who express resistance by attacking the symbols of their oppression.

Considering the destruction of the Mosul Museum in light of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1964 film Bande à part (Band of Outsiders) underscores its interpretation as a subaltern communicative act already integrated within Western aesthetic forms. In this film, a group of teenagers runs through the Louvre Museum in nine minutes and forty-three seconds, which is carefully measured and announced by the narrator in the language of positive authority that the film critiques. A documentary-style voiceover, as well as a moment lingering in front of Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii of 1784, suggests revolution rather than mere defiance. If we understand David’s painting as a call to arms in which the loss of life, for which the female figures mourn, is a necessary price for the fomenting French Revolution, then we understand the race through the museum as deposing the cultural capital of the museum and the hegemonic order that it represents. Although the characters destroy nothing, the desire to run through the museum undermines the sobriety of high culture. The ludic inversion of order in the film resembles the pleasurable destruction of the museum in the video—in a context of civilizational war, it becomes a liberating gesture against a much larger hegemonic order, agency in an arena of foreclosed speech.

The ISIS video authorizes its destructive expression by mimicking the format of a museum documentary, replacing the secular language of worshipful admiration articulated by an expert before the object with that of an ISIS preacher, inciting destruction. Like Andrea Fraser mocking the manipulative intimacy of museum audio-guides in Little Frank and His Carp (2001), the ISIS video parodies the metanarratives inherent in the power to own antiquities and the expertise to narrate their meanings. The video begins with an introductory sequence depicting the benefits of ISIS power and resembling the promotional sequence of a television show. It then offers a full-screen pan of the museum, showing many sculptures in plastic sheeting, to the sound of Qur’anic recitation. Much as the camera in a museum documentary might sensuously linger over the forms of a museum object, in the ISIS video men gently disrobe the statues. In contrast to the displaced sensuality of the gaze in the museum documentary, the tactile relationship with museum objects in the ISIS video affiliates the scene with the promises of sexual fulfillment used as bait for prospective ISIS recruits as well as with the rape implied in the violence of the objects’ destruction. English titles begin in the next scene, showing a sermon by a man standing in front of a large statue of the Assyrian protective deity Lamassu. As a hand-held camera pans between the labels and antiquities, the expert in the mock-documentary offers Islamist rather than art historical information, defining the work as an idol and modeling the appropriate response to it through the prophet Muhammad’s transformation of the pre-Islamic Ka’aba into the nexus of Islamic worship—not through the veneration of objects, as in a church, a museum, or a documentary, but through their destruction.

While biographies of the prophet record this event, for most of Islamic history it remained minor next to the numerous stories of revelation, personal and public action, and battle that make up the key elements of his biography.13 Discussions of compiled deeds and sayings of the prophets (the hadith), which form the basis of Islamic law along with discussions of the Qur’an, exclude this incident as legal precedent for limitations on the use of the image.14 The destruction of the idols emerges as a key element of the prophet’s biography in Moustapha Akkad’s widely disseminated film of 1976, which was made with two sets of actors in Arabic and in English, entitled, respectively, al-Risale and The Message. The film avoids representation of the prophet by staging the camera from his perspective, effectively placing the viewer in his shoes. The climax of the film includes a long sequence suffused with tense, mysterious music in which his walking stick knocks down the idols housed in the Ka’aba, symbolizing the victory of Islam over preceding paganism. Probably intended as a nonviolent staging of the prophet’s leadership, the film effectively constructs an iconography of iconoclasm.

Such an iconography of iconoclasm—a visual sign system depicting contemporary understandings of Islam as eschewing visual representation—has become a dominant theme in the tension between the West and the Islamic world. Reflective of racial distinctions between Aryans and Semites established in analyses of Judaism and Islam in nineteenth century Orientalism, the supposed prohibition of the image in Islam has been a central feature in descriptions of Islamic art since the early twentieth century.15 Despite the absence of any explicit ban on images in Islam, this interpretation has become increasingly pervasive in recent decades, beginning with objections against the representation of the Prophet Muhammad at the Supreme Court in 1997 and becoming particularly virulent after the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan by the Taliban in March 2001. Labeled as the “beheading” of the statues in the documentary footage circulated at the time, the event served as a propagandistic opportunity for the Taliban to grandstand against the Western “idolatry” of valuing material heritage over local lives.16 Subsequent controversy over cartoons in Denmark in 2006 and terrorist attacks on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015 have further cemented the political utility of the contemporary Islamist iconography of iconoclasm in the public sphere, repeatedly portraying Western discourses of free expression as “idolatry” pitted against a self-righteous narrative of neocolonial oppression attracting broad sympathy in the Islamic world.

Patrick Chappatte, Mosul Museum Devastated, 2015. Published in Le Temps, Switzerland, February 28, 2015. © Chappatte 2015.

The ISIS video replicates this iconography as the introductory sermon ends, explaining, “Since Allah commanded us to shatter and destroy these statues, idols, and remains, it is easy for us to obey.” The narrator’s discourse then shifts sins, addressing the dissemination of idols rather than their worship, as he explains, “and we do not care [what people think] even if this costs billion of dollars.” He references the widespread accusations of extensive looting of archaeological sites in the Levant and a subsequent increase in black market antiquities trade helping to fund ISIS. This absolution of sin addresses viewers unaware that the difficulty in transporting such large works would make them far less valuable on the market than smaller works that have proliferated in the current war economy.17 For more sophisticated interpreters, rejoinders have circulated that mostly plaster casts were destroyed.18 Whether or not such discussions ultimately prove to be accurate, like the ISIS video, these discussions function symbolically, assuaging the pain of loss by de-authenticating it. Remaining on the register of preservation ideology, such discussions fail to listen to the reasons why the destruction of the Mosul Museum might be understood as positive propaganda to its target audiences. Beyond the physical “war on terror,” only unraveling this appeal can ultimately counter the propagandistic power of groups like ISIS.

The main body of the video, featuring the slow-motion destruction of objects to a soundtrack of Qur’anic recitation, uses a written quotation from the Qur’an (chapter 21:58), “he reduced them to fragments,” to conflate the act of Muhammad at the Ka’aba with that of Abraham, often interpreted in Islam as a figure foreshadowing Muhammad’s prophecy. Parallels with the Jewish Midrash B’reishit Rabbah 38:13; the Biblical book of Deuteronomy 12:3, enjoining the people of Moses to smash idols as they enter Jordan; and the book of Micah 5, which specifically describes the entry into Nimrod in the subsequent destruction of Assyrian idols, underscore the shared roots of the three religions, all of which include discourses that could potentially repudiate imagery.

The irony of Biblical archaeology is that in defending the Bible, it sought to prove the literal veracity of the Bible by reviving these very “idols” that Biblical figures ordered destroyed. Emerging as a means to prove the veracity of the Bible after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species in 1859, Mesopotamian archaeology enabled the construction of a modern, secular narrative of Western Civilization mapped onto the narrative history of Western Christianity. Enshrined in encyclopedic museums, this Eurocentric narrative of global history excludes the intertwined networks of numerous cultures.

As museums proliferated across the world in the twentieth century and photography began to record all aspects of human aesthetic production, Louvre Museum Director André Malraux reflected on the universalist ideal in his long-running archival project Les Voix du silence / Museum without Walls, begun in 1947. “For a long time,” he explained, “the worlds of art were as mutually exclusive as were humanity’s different religions … each civilization had its own holy places … now discovered as those of the whole of humanity.”19 The destruction of the Mosul Museum suggests that this vision of a happy world in which culture is flat and equally owned by all does not exist and never will. Museums have walls because we do not live in a giant museum but in a world where objects function within contingent and contested economic and symbolic economies of power. If we think of museums as temples, complete with systems of ritual and reverence, then the objects within them reemerge as icons of the modern renditions of history.

For people in the Ottoman Empire, where these excavations took place over a century ago, the apparent value of archaeological sites had no relationship with ancient texts. As in Geyre, in many places artifacts emerged as part of hoeing the land, and were sometimes incorporated into buildings, landscape, and even local lore. Identified with place rather than time, they functioned as signs of a continued presence of habitation rather than through scientific links with precedent cultures. In 1913, Hüseyin Zekai Pasha, an Ottoman administrator and painter, wrote a book entitled Holy Treasures designed to introduce readers to a new type of value associated with public sites, including all sorts of historical architecture and archaeological sites.20 Unlike the literary contextualization of archaeological finds in Europe, Zekai pragmatically suggested that the participation in the practice of science engaged them with civilization. For him, the “castrated” ruins of Baalbek served as a memento mori of failure for which museums offered a cure, by showing “how humans somehow are unable to maintain power from ancient times through the undeservedly luminous light of their intelligence which they tend to spend and consume due to covetousness and emotions.” Rather than relying on historical narrative, he understood archaeology as a praxis of contemporary civilized behavior that would protect the empire from the fate of empires past.

By the mid 1950s, when the Turkish poet Yahya Kemal Beyatlı (1884–1958) looked back on his life, this worldview had become fully integrated into a simultaneously religious and national perception of pleasure. In his poem lamenting old age, “Thoughts of the Way,” he explains:

Not the dawn over the Mediterranean,

nor the evening in the desert,

Not the Nile that I longed to see,

nor the ancient pyramids,

Not the classical ruins of Baalbek,

nor the magical place of Adonis at Biblos,

Not this magnificent land of hanging oranges,

Nor the rose, nor the tulip, nor the banana,

nor the date and the pomegranate,Not the refrains that fill the Damascus sky,

Nor the old Raki from the Zahle grape,

None gave me the pleasure that I miss from fate, alas!

One who senses this at the beginning and not at the end said,

“Faith gives a person pleasure even on the cross!”

I said, “But Jesus was also young then.”21

His imagery draws simultaneously on a cultural inheritance that is Ottoman and Islamic, and which includes archaeological and Christian legacies as part of a regional civilizational pride. While, in his old age, he may no longer enjoy food, tourism, or even the pleasure of faith, it is clear that for him the celebration of the ancient has become part of his contemporary cultural capital.

Jewad Selim, Baghdadiat (Two Women), 1957. Oil on canvas, 27⅛ × 21⅓ inches. Courtesy Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

Similarly, archaeology became a central element of national identity construction in the Levantine states emerging from the Ottoman and European imperial eras, and including Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. These new nation-states translated Western interest in the local history of Western Civilization as proof of the nation’s role at the root of civilization and as a means of harnessing ancient glory into a promise of future success. In Iraq, the Baghdad Artists’ Group, formed in 1951, appropriated multiple strands of local histories—recouped through European archaeology, art history, and religious studies—into a modernist art rooted in Cubism. They invented an apparently authentic Iraqi modern art as an amalgam of styles that projected a unified cultural identity onto the nation, but its hybrid visual languages could only be fully comprehended by the educated elites.22

Under Saddam Hussein, the revival of Assyrian identity provided ancient precedent for a strong central state while providing a source of collective identity preceding all modern religious and ethnic groups in the region. In the 1950s, a reproduction of the Ishtar Gate (the original of which was excavated between 1902 and 1914 and is at the Berlin Pergamon Museum) was built as an entryway to the remnants of the city of Babylon, 85 kilometers south of Baghdad. The reproduction used bricks bearing the inscription, “This was built by Saddam, son of Nebuchadnezzar, to glorify Iraq.”23 In the 1980s, a massive billboard portrait of Saddam Hussein towered above it. Mass looting in Iraq began to grow rapidly after the imposition of sanctions in the 1990s. After the United States invaded Baghdad in 2003, over 13,000 objects were estimated to have been looted. Throughout the region, the trade of illegal antiquities spread as a young population grew up without the historical and heritage education necessary to give museum objects value.24 During the same period, the Ishtar Gate became a popular site for souvenir photos among U.S. soldiers.

The destruction of the Mosul Museum thus embodies not simply the overthrow of global narratives of Western Civilization and heritage, but more recent nationalist legacies. No museum is fortress enough to shelter artifacts without the shield of stories that give them value. If archaeology is to retain its worth in the contemporary era, we must ask the types of questıons Hüseyin Zekai addressed a century ago: What role can artifacts play in our culture? If they no longer explain a tenuous narrative called “Western Civilization,” how can we incorporate them into collective stories? If the national narratives that held up antiquity as forefather and future no longer have nations to call home, then what new narratives can antiquities hold in local contexts?

Lida Abdul, Clapping with Stones, 2005. Stills from 16 mm film transferred to DVD, 5:00. Courtesy Giorgio Persano Gallery.

We must begin to look at heritage in the future tense, not as a revelation of what an imaginary collectivity called “we” has been, but of what we can become with these objects, revitalized from their burial in time, in our midst. We can imagine this new presence as in Lida Abdul’s Clapping with Stones (2005), where she aims to “preserve ruins for the future. Just as ruins. Not Monuments.” In contrast to the bourgeois King Ubu’s restitution of destruction through monumental preservation, Abdul films men clapping with stones from the ground near where the Buddha sculptures were blasted to bits, giving voice to the Buddha through the remnants of his absence.

Lida Abdul, Clapping with Stones, 2005. Stills from 16 mm film transferred to DVD, 5:00. Courtesy Giorgio Persano Gallery.

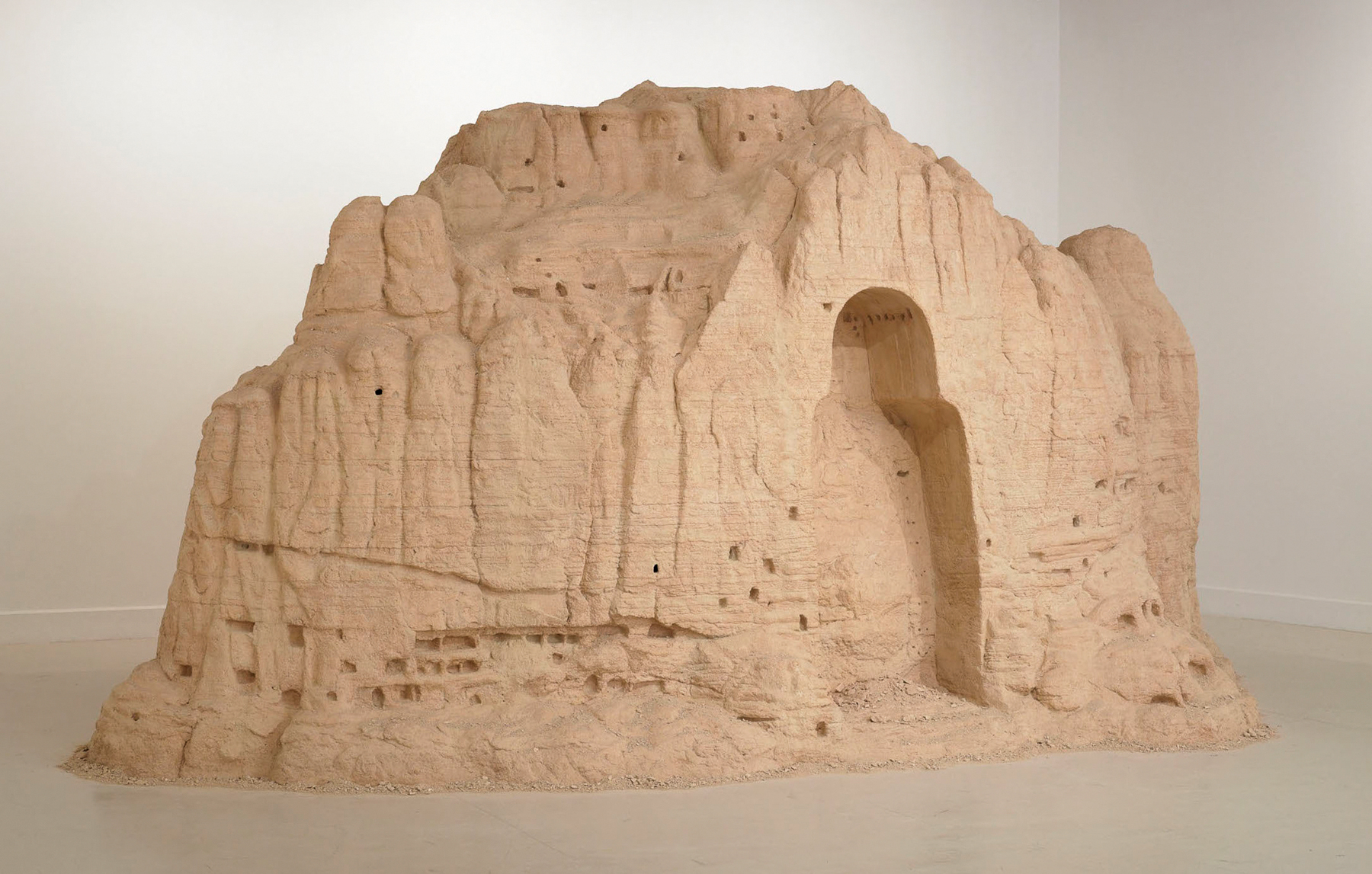

Similarly, Subodh Gupta’s Renunciation (2013) used 3-D imaging technology to build a scale model of the mountain with the niche where the Buddha was destroyed. Visitors remember the absent statues and the cave dwellings surrounding them by peeking through holes in the mountain, viewing a secret cave of riches. As in the earliest representations of the Buddha, which consist simply of a wheel or an empty niche, the site becomes all the more powerful for the absence that has made it far more present in the public consciousness than it ever was before its destruction. Perhaps more than the reconstruction of the destroyed sculptures, the incorporation of memory into contemporary culture plays a strong role in evoking the multifaceted meanings of loss. Using colorful local packaging materials to reconstruct the artifacts lost to the Baghdad Museum after the United States invasion of 2003, Michael Rakowitz’s installation The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (Recovered, Missing, Stolen Series), exhibited at the Sharjah Biennial in 2007, invites the viewer to juxtapose works often familiar from the early pages of art history textbooks with materials evocative of contemporary living culture. In contrast to the efforts of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, Rakowitz’s installation thus juxtaposes rather than blends antiquity with contemporary visual culture. In his work in progress, Material Speculation: ISIS (2015), Morehshin Allahyari entombs digital records within 3-D-printed resin reproductions of artifacts recently destroyed by ISIS.25 The work explores contemporary technologies of recreating the ghosts of lost artifacts while recognizing the impossibility of unlocking their lost cultural resonances. Rakowitz’s and Allahyari’s works point to the irony of incorporating a lost past into the present without rejecting either the legacies of antiquity or the modern processes that have articulated it within multiple ideological narratives, whether globalizing, nationalizing, or iconoclastic.

Subodh Gupta, Renunciation, 2012. Mixed media, 126¾ × 257⅓ × 141¾ inches. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: José Luis Guitérrez.

Morehshin Allahyari, Material Speculation: ISIS, Lamassu, 2015. 3-D print in clear resin and USB drive containing PDF files, images, and videos. Courtesy of the artist.

The vision of a world with a shared history is as profoundly modern as it is optimistic, but this makes it neither mandatory nor universal. Arguing for a future in which heritage preservation emerges through the coming together of “several worlds, with differing visions of heritage or legacy, can come into contact, communicate, and negotiate those differences,” Dario Gamboni recognizes that André Malraux’s triumphal 1957 vision of the world as a museum without walls neither recognizes that images function in a real world, nor fits contemporary notions of cultural diversity.{{26]][[26]]Gamboni[[26]] Yet Malraux’s observation that “dying fetishes have taken on a significance they never had before, in the world of the images with which human creativity has defied the passage of time, a world which has at last conquered time,” perhaps has never rung quite so true. The fetishes dying today are not religious fetishes subsumed into secular museums, but the narratives that underlie the power of museums.

Michael Rakowitz, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (Recovered, Missing, Stolen Series) (detail), 2007. Statue: male, bearded, long hair, bare-chested, wearing flounced skirt, hands folded, eyes inlaid with shell, hair painted with bitumen; dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Rather than supporting notions of “universal heritage” as imagined by international bodies like the United Nations, these narratives have supported the destruction of local identifications and have enhanced the class distinctions established through the circulation of cultural capital. While the destruction of antiquities has no tangible benefit to anyone, its effectiveness as provocation underscores the divisive symbolic power vested in antiquities. Rather than simply calling it a crime, we must listen to the subaltern counter-narratives that give this destruction symbolic power, and use this knowledge to construct a more inclusive, more complex understanding of archaeological legacies beyond the paradigm of universalism. If Hüseyin Zekai Pasha lived today, he might enjoin us to participate not in science so much as in the re-inscription of complex and networked legacies as addressed by contemporary art. Reconsidered as art rather than as war crime, the video documentation of the destruction of the Mosul Museum becomes an act of creative destruction, suggesting modes of heritage as invested in the local as the global, in absence as in presence, and in listening against the grain to the multiple messages vested in symbolic action.

Wendy M. K. Shaw is Professor of the Art History of Islamic Cultures at the Free University, Berlin.