Of the more than 60 Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA exhibitions dedicated to Latin American and Latino art, only two dealt with the question of the Caribbean’s relationship to Latin American cultures and histories. Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago took place at the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) in Long Beach, and was curated by Tatiana Flores. PST: LA/LA’s concentrated, region-wide focus on Latin American art offered MOLAA a unique opportunity to engage with underrepresented communities within the cultural space defined by the museum’s focus on Latin American art. Circles and Circuits I: History and Art of the Chinese Caribbean Diaspora, at the California African American Museum and Circles and Circuits II: Contemporary Chinese Caribbean Art, at the Chinese American Museum in Los Angeles, was curated by Alexandra Chang and Steven Y. Wong, and opened a window into the complexities of Caribbean ethnicity, which intersects with a variety of Asian, African, and indigenous Diaspora communities. Both exhibitions featured strong Southern California debuts from Caribbean born artists and introduced to the West Coast a conversation about culture, history, and philosophy from a complex region. Relational Undercurrents and Circles and Circuits expanded the definition of “Latin American” to include African-and Chinese-descended artists, reflecting migration patterns that were only sporadically addressed in the larger Getty-led PST: LA/LA initiative. At the same time, the decision to approach the southern hemisphere from the perspective of shared European languages, rather than geography, might create the mistaken impression that the people of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean are culturally isolated from their Francophone and English-speaking neighbors, and thus more closely connected to Mexico, Brazil, or Chile than to Haiti or Jamaica. The question of representation—of how the presentation of Caribbean cultures functions institutionally and socially within the Southern California context—must therefore be addressed with respect to both the structure and the content of the exhibitions discussed.

Firelei Báez, Man Without a Country (aka anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River), 2014/15. Gouache, ink and chine collé on 220 deaccessioned book pages, 108 x 252 in. Photo: Oriol Tarridas Photography / PAMM.

Relational Undercurrents is an immense exhibition including more than 80 artists, arranged in a constellational display according to visual and thematic affinities that are loosely threaded throughout several interlocking galleries at MOLAA. Recurring motifs include the ocean, the map that assigns groups of islands to one another and to the continent of Latin America, and the distributed network of the archipelago. Firelei Báez’s paintings on maps and book pages render the historical remnants of colonialism surreal, populating them with flowering figures and occluding dots that proliferate like cancer. Tania Bruguera’s white-on-blue postcard map, bearing an amalgamated Pangea of continents, entreats the liberation theologian Pope Francis to ally with stateless people and refugees, as the Vatican serves as a national home for Catholics around the world. Sculptural assemblages of found materials reference the tourist trade in In My Floating World: Landscapes of Paradise (2010), by Scherezade Garcia, and the pollution of the ocean waters in Mar invadido (2015), by Tony Capellan. Both artists use a blue-green-grey palette evocative of Caribbean skies and seas. Elevata (2002), a large photographic composite in 16 panels by Maria Magdalena CamposPons, maintains the blue sky-ocean reference. Campos-Pons, an Afro-Chinese-Cuban artist, uses her body to add the punctum of forced African migration to every image she creates, with the artist appearing, inverted, at the top of the frame and her long twists of hair mapping out circuitous paths. Artists in Relational Undercurrents engage the history of contemporary globalization as it has been written into the Caribbean landscape. First contact between indigenous Americans and Europeans in 1492, when Columbus met the Taíno people and dubbed them “Indians,” was the inciting act of violence that birthed the New World. Sasha Huber’s portrait of Columbus, Shooting Back—Reflection on Haitian Roots, Christopher Columbus (2004), is a portrait of the explorer made from metal staples in a weathered plank of wood. Each propulsion and puncture that makes the image reverses the direction of the violence enacted by the colonial project. The transatlantic slave trade quickly followed, with the Middle Passage—the lengthy traversal of the mid-Atlantic by slave ships that left thousands of African captives dead at sea and millions more with the epigenetic trauma of cultural rupture, annihilation, and enslavement—terminating in the Caribbean islands. Carlos Martiel’s Punto di Fuga / Vanishing Point (2013) is a documentary video of a performance in which the artist had threads sewn into his skin in the front and back of his torso, and pulled. The artist’s Black body, subjected to pain, is the mirror image of the horizon that called the Spanish colonizers to exploration at sea.

Tania Bruguera, The Francis Effect, 2014. Arte de Conducta performance, canvasing campaign. Courtesy of Estudio Bruguera. Photo: Gaetano Olmo Stuppia.

The merchant marines, and the missionaries that followed, played a crucial early role in transforming the region, seeding Hispanic culture in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic. The path of Spanish missionaries still determines the contemporary political boundaries of Latin America. In an essay in the exhibition catalog, Flores argues for a definition of Latin America that is broad enough to include the French-and Dutch-colonized islands of Haiti and the Antilles and the British and Danish Virgin Islands, Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica. Anti-imperialist and post-colonial independence movements, like the exploitation that preceded them, likewise begin in the Caribbean, with the overthrow of French colonial troops in Haiti by Toussaint l’Ouverture’s popular revolution in 1804. Haitian artists in the exhibition include Miami-based Adler Guerrier, whose peripatetic explorations of Miami add an Afro-Latin twist to the French Situationist dérive. Didier William, based in Philadelphia, is represented by a painting, They play too much till we stop playin (2015), in which shadowy forms lurk within a composition of patterned surfaces bearing the image of the Vodoun deity Papa Legba, an intermediary known to facilitate communication with the spirit world. One figure is completely covered in eyes, which are etched into the painted wood surface. The artist’s block-printing technique causes the work to hover between painting and printmaking, as tenuous a border as that between representation and abstraction, or that between the material and the supernatural world.

Sasha Huber, Shooting Back — Reflection on Haitian Roots, Christopher Columbus, 2004. Metal staples on wood, 31 ½ x 45 ¼ in. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

As colonial guilt over the consequences of forced labor on the dwindling indigenous population gave rise to the African slave trade, so too did the rising wave of abolitionism in the early nineteenth century make way for an influx of destitute and abused Chinese and South Asian Indian indentured laborers in the Caribbean. This lineage is reflected in the premise of Circles and Circuits. The historical section of the exhibition at the California African American Museum focused on key historical figures of the early twentieth century of Caribbean-Asian parentage, including the widely known Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (1902–1982), whose Afro-Latino heritage has been explored by scholars including Lowery Stokes Sims, but whose Chinese heritage is less familiar. Lam’s Fata Morgana (1942) and Interlude Marseille (1940), on loan to the exhibition from private Los Angeles collections, make reference to the artist’s escape in 1941 from Vichy France, via a safe house in Marseille, to the Caribbean island of Martinique, and ultimately to the United States, in the company of his surrealist peers André Breton and André Masson and the celebrated ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. The story of their flight as told by the artworks illustrates a tenet of contemporary Caribbean culture, which is to interweave and overlap the remnants of cultural legacies from Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas into new and distinctly regional cultural forms.

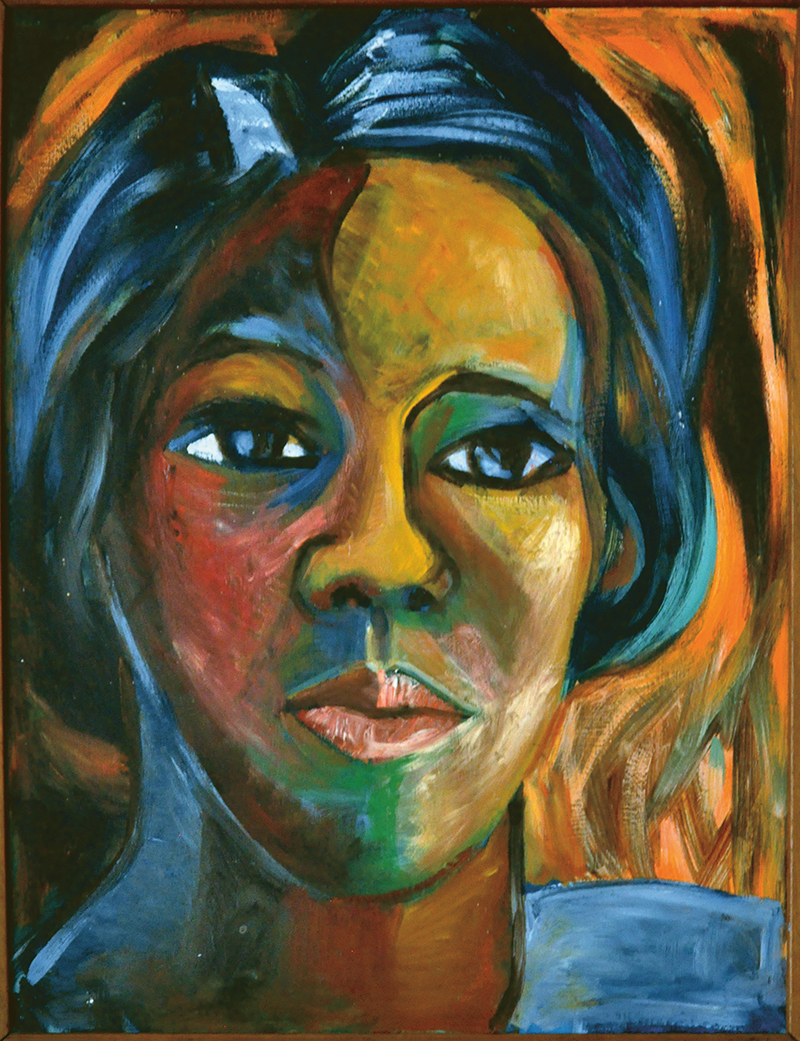

While the exhibition’s documentation of Lam’s lesser-known Chinese heritage adds new shades to this complex and prescient historical figure, the true revelation here is Trinidadian painter and arts organizer Sybil Atteck (1911–1975), whose work is virtually unknown in the United States. Atteck was the founder and heart of the Trinidad Arts Society (now the Art Society of Trinidad and Tobago), and a bridge between the local artists of Port-of-Spain and the surrounding islands and the international discourse of modernism that was rapidly becoming art-world currency. Educated in London and St. Louis, Missouri, Atteck studied with the venerable Expressionist painter Max Beckmann, who was in exile from Nazi Germany and teaching at Washington University. Atteck’s generosity continues to be celebrated by the artists of Trinidad and Tobago, who view her as a connector between their regional cultural milieu and the international trends and perspectives which the artists disseminate and recombine with their own regional traditions and aesthetics. Atteck’s vision to create and maintain a space for Caribbean artists to exhibit and collaborate is at the center of the web of relationships that anchor Circles and Circuits in a historical mid-century moment. In addition to Lam, Atteck promoted the early work of writer Cyril Lionel Robert James and painters Mahmoud Pharouk (aka M.P.) Alladin (1919–1980) and Carlisle Chang (1921–2001), whose works hang adjacent to her own. Atteck’s paintings are ambitious and her painterly hand is supremely confident. Her color palette is unapologetically bright, reflecting the tones of the Caribbean landscape. Her use of Primitivism is complicated, as is Lam’s, by her identification with a culture coded as exotic and anti-modern by these European tropes.

Sybil Atteck, Self-Portrait, c. 1970. Oil on board, 28 x 22 in. Collection of Helen Atteck.

The Jamaican-British theorist Stuart Hall, a generative thinker in the field of Caribbean discourse, invoked organizational management theorist Paul du Gay’s “circuit of culture”1 to describe how visual representation inscribes self-identification in art, breaking this process up into five elements: representation, identity, production, consumption, and regulation. According to Hall, meaning is produced by the interplay of these elements within culture, rather than by any one aspect independently. “Meaning,” he writes, “is what gives us a sense of our own identity, of who we are and with whom we ‘belong’—so it is tied up with questions of how culture is used to mark out and maintain identity with in and difference between groups.”2

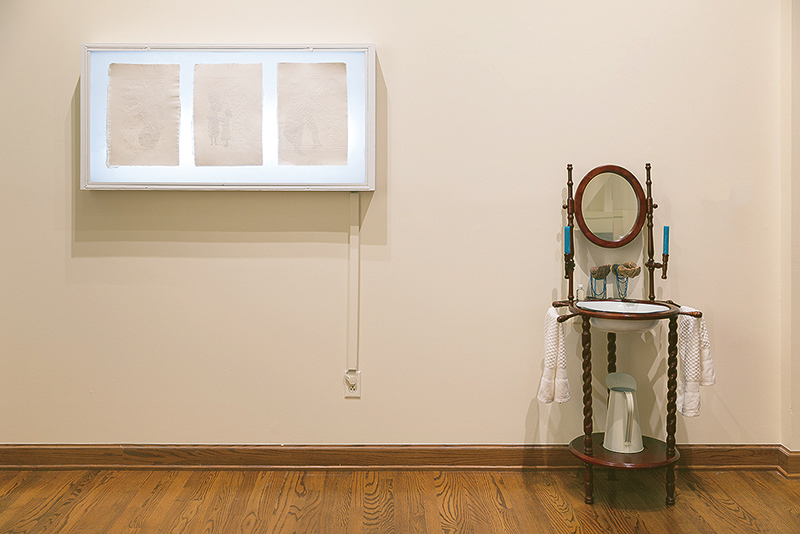

When Atteck or Lam engages Primitivism, the forms may resemble those of Pablo Picasso or Masson, but the meaning is deepened by a question of belonging that never fully resolves. Contemporary Caribbean artists of Chinese heritage, whose work is collected in the Circles and Circuits iteration at the Chinese American Museum (CAM), seem to be more comfortable with motif than with meaning, relying on material and spatial frameworks that rarely stray from narratives of identity and heritage. A few works stand out, including wall-hung sculptural collages by Nicole Awai that comprise maps, nail polish, and molded plastic, and Albert Chong’s composite photographs, which incorporate archival images and historical narratives in evocative ways. Andrea Chung’s delicately embossed white prints confronting the racist history of scientific exploration in the Caribbean are a highlight, while her sacramental hand-washing basin, reminiscent of religious rites, must be activated with the caress of a sculpted soap hand that emerges fixture-like from the wall. The history of enslaved African bodies being represented sculpturally as architectural features, as a visual rhetoric of subjugation, melds with the more recent impression of the Vatican’s turn toward liberation theology to produce a swarm of conflicting meanings that the viewer must parse. The domestic space of the home, with the gesture of hospitality represented by the washing of hands, suggests yet another reading of the work.

Andrea Chung, Red Raspberry, Dandelion, Marigold, 2016. Handmade paper made of handkerchief used by nana midwives and red raspberry leaf tea embossed and embedded paper over lightbox, lightbox: 24 ½ x 49 ¼ x 4 ½ in. Courtesy of the Chinese American Museum. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Andrea Chung, Pure, 2016. Cast black soap, dry sink, towels and candles, 51 ½ x 24 x 21 in. Courtesy of the Chinese American Museum. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

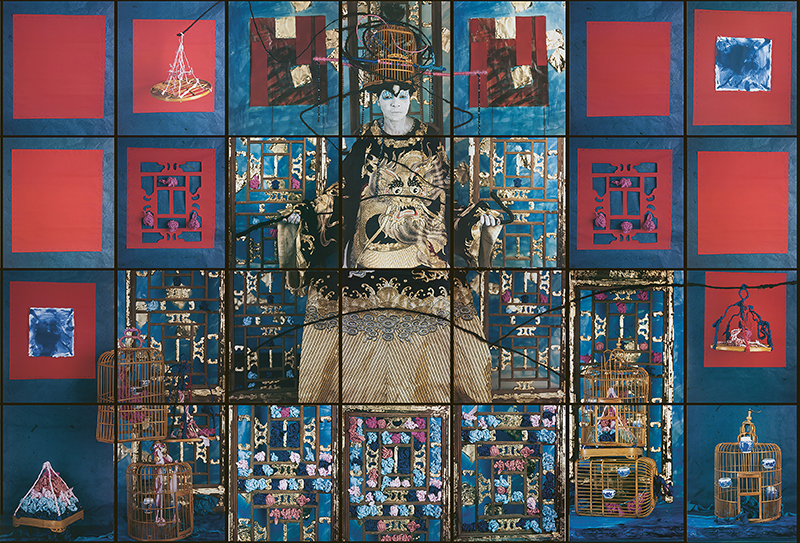

What meanings are produced by introducing Caribbean artists to Southern California under the rubric of “Latin America”? Who is served by inclusion in the group, and who is left out? Caribbeans are not a large community on the West Coast, but including the Caribbean enables the Getty to appeal to African Americans in addition to Chicanx and Central American constituencies, all significant local political blocs. The global contemporary art market continues to attract cultural producers from developing economies who find opportunities for greater support and visibility working internationally than working locally, and international biennials, such as the Havana Biennial and the Ghetto Biennale in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, have given Caribbean artists a point of entry. These events serve an economic development purpose as well, boosting tourism and trade to the larger region. Art stars have emerged, many represented in the exhibitions here. Campos-Pons is one whose work appears in both Relational Undercurrents and Circles and Circuits. She is represented in the latter exhibition at CAM by a large composite photographic self-portrait in which her body, which as before stands in for the commodified African body of the transatlantic slave trade, is juxtaposed with objects of chinoiserie that circulated alongside Chinese and African laborers as tradeable commodities in the colonial period. These objects, the wall label tells us, shifted their vernacular meaning in the global stream, becoming staples of Santería rituals within their new Cuban context.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Finding Balance, 2015. Composition of 28 Polacolors, 154 x 104 in. Courtesy of the artist and Samsøñ, Boston.

Syncretism occurs when the symbolic trappings of an above-ground system of belief are used as ciphers to create space for continuing cultural practices that have been pushed underground by colonization and social repression. This term is most often used to refer to religious practices, such as the tendency of Yoruba deities to reappear, with the names and faces of Catholic saints who share their attributes, in plantation societies, including the Caribbean, Brazil, and the Southern United States. More recently, this practice in linguistics and political rhetoric has been called code-switching, which the artists in both exhibitions do abundantly and well. As this work is poised to be consumed by collectors and institutions worldwide, how is its meaning framed through the institutions where it is presented—here, the Museum of Latin American Art, the California African American Museum, and the Chinese American Museum? These ethnically specific institutions are open to recognize and celebrate cultural affinities internationally but also must be responsive to the needs and interests of generations of constituents based in the Southern California region. To do so, institutions must be open to code-switching and subterfuge, as reflects the experiences of many audiences of color who experience culture differently in public spaces, such as the workplace or school, than they do at home. Institutions must not commit exclusively to the work of respectability and reconstruction within a nationalist or neoliberal paradigm, which often serves to treat the concerns of communities of color as problems of “fit” within a benign mainstream culture, rather than ask difficult questions about the structural inequalities that beget contemporary systems of power. Most importantly, culturally specific institutions must be prepared to write the unwritten histories that show their constituents the fullest possible image of themselves, inclusive of their struggles as well as their victories, and incorporating the voices of people who remain marginalized even within such affinity groups.

Circles and Circuits I: History and Art of the Chinese Caribbean Diaspora, installation view, California African American Museum, September 15, 2107–February 26, 2018. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Through these institutional lenses, communities with less visibility in Los Angeles, such as South Asians, are less visible in the construction of “Caribbean” than they might be in fact. Circles and Circuits includes a single South Asian identified artist—Alladin, whose impact on Trinidadian contemporary art was significant. Alladin served as Director of Culture in the Ministry of Education and Culture from 1965 until the late 1970s and published several books on regional art. His work is a revelation in the exhibition, synthesizing the Afro-Latino rhythms and hues found elsewhere with the sensibilities of South Asian modernist painters active in the same time period. His contemporary, Carlisle Chang, is representative of many Trinidadians in that he claimed no such heritage by birth but was steeped in a South Asian cultural upbringing, even joining Arya Samaj, then a modernizing movement among Hindu Indians globally.3 As the definition of “Latin America” is expanded by the inclusion of the Caribbean, here we see how the cultural expanse of the Caribbean might be narrowed by its regulation through Pacific Standard Time’s Latin American and Latinx focus.

Carlisle Chang, Woman with Chickens, 1958. Oil on board, 23 ½ x 35 in. Courtesy Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago.

Stuart Hall argues for an intersectional approach to culture, which should be applied to viewing Caribbean contemporary art in that the whole system of production around a given image or object—and not simply its chosen language of signs, symbols, materials, and forms—must be evaluated in order to assess a work’s meaning. Relational Undercurrents is organized around the idea that the unifying factor of the Caribbean is the shared experience of displacement, marked by extermination of indigenous communities and importation of African and Asian forced labor. The exhibition proposes an archipelagic4 approach to curating, in which different perspectives are arranged in an intuitive fashion, allowing affinities to emerge organically through proximity. The exhibition is inclusive of non-Hispanophone artists, encompassing Haiti, the British and Dutch Caribbean, and the US protectorate of Puerto Rico, which is often excluded from geopolitical definitions of the region due to the absence of independent government. Indigeneity, with which many Latin Americans identify, is more ephemeral in the Caribbean, where African, European, and Asian inheritances have been more visible. Still, Taíno origins have been claimed by Caribbean peoples in the twentieth century, and more recently, DNA analysis has identified genetic markers found in the tooth of a 1,000-year-old indigenous woman found in Eleuthera, Bahamas, as present in the majority of Puerto Rican people living today, a finding researchers expect to corroborate in other Caribbean populations.5 With so many ethnic and cultural influences, positioning Caribbean art within the often strident nationalist narratives of postcolonial Latin American independence, US border imperialism in Mexico, and US-style identity politics presents a challenge, in the same way that the poetic, slippery, and culturally voracious ethos of Caribbean discourse, as articulated by C. L. R. James, Aimé Césaire, Édouard Glissant, Paul Gilroy, and others, challenges established ethno-political alignments. Relational Undercurrents and Circles and Circuits represent two significant efforts to realign conventional misconceptions about geopolitics and global art that are widely held in the global North and overdue for a substantial rethinking.

Anuradha Vikram is a writer, curator, and educator based in Los Angeles. She is Artistic Director at 18th Street Arts Center, core faculty in the MFA Social Practice Area Emphasis at Otis College of Art and Design, and a member of the board of the College Art Association. Her first book, Decolonizing Culture, was published by Art Practical/Sming Sming Books in October 2017. She is a member of X-TRA’s Editorial Board.