All learned professors and doctors are agreed that children do not comprehend the cause of their desires; but that the grown-up should wander about this earth like children, without knowing whence they come, or whither they go, influenced as little by fixed motives, but guided like them by biscuits, sugar-plums, and the rod—this is what nobody is willing to acknowledge; and yet I think it is palpable.

—Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther, 1774

Black wraparound shades, white Japanese racing bike, electric green bikini: Frances Stark strikes a daring contrapposto on the cracked and faceted blankness of the Bonneville Salt Flats. Total Performance (1990) is one of Stark’s earliest pieces, yet the photograph already displays many of her work’s defining conceits—from a studied nonchalance to a self-aware and self-centered approach to gendered archetypes to a dramatic use of empty space. Horizon and ground pressurize the figure; she is bared and scrutinized; she is also kinetic and dazzling. Pending there in the deserted expanse is not the striding east-coast cowboy of Robert Smithson or Michael Heizer, but Stark—self-portrait as sex bomb.1

SONG: So—you never really loved me? Only when I was playing a part?

GALLIMARD: I’m a man who loved a woman created by a man. Everything else—simply falls short.

—Henry Hwang, M. Butterfly

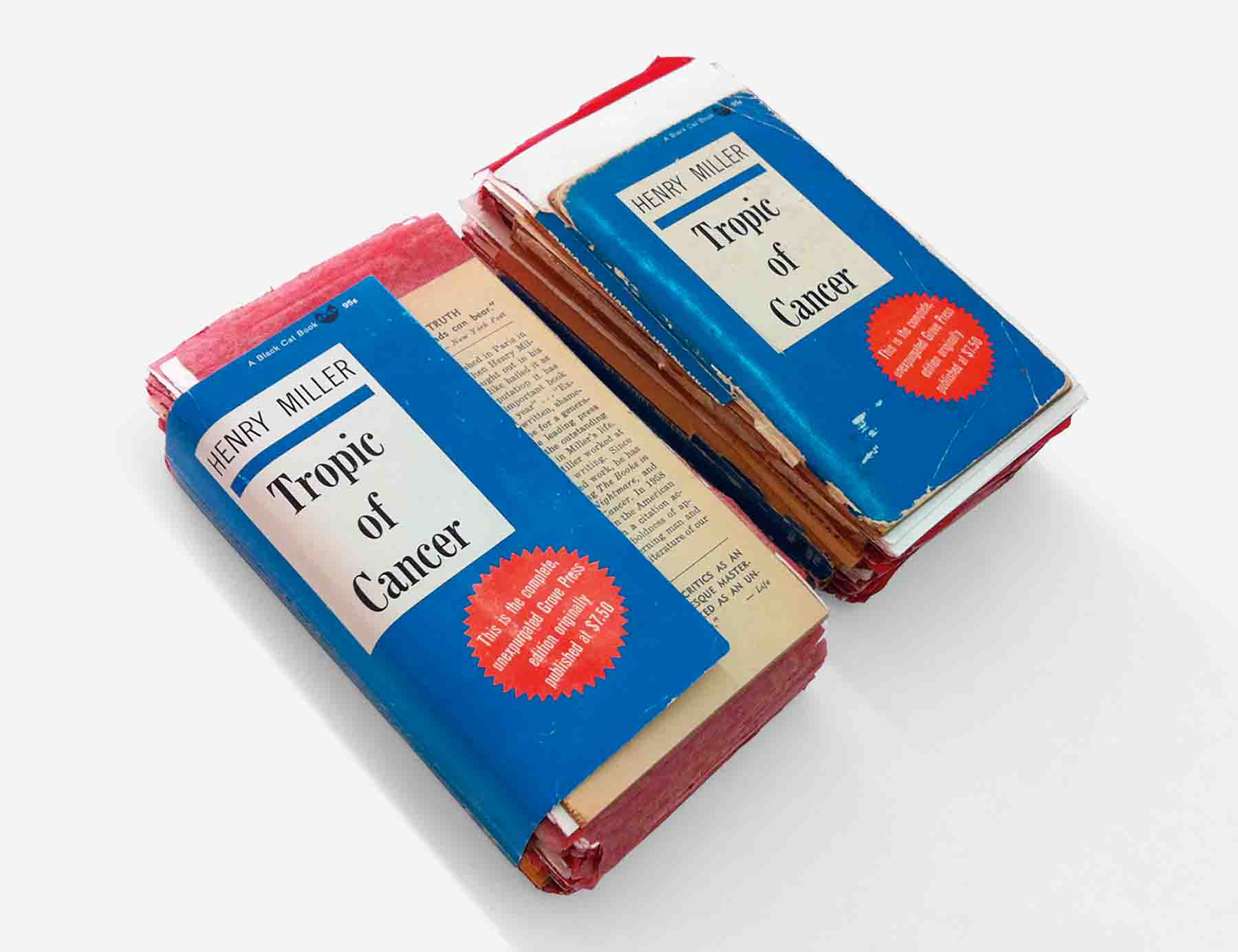

In several drawings and collages from the 1990s and early 2000s, Stark formalizes her relationship to an often literary patriarchy. In Untitled (Tropic of Cancer) (1993), two copies of Miller’s novel lay immobilized in a vitrine, drawing paper and carbon stuffed between every page.

Frances Stark, A Bomb, 2002. Gouache, carbon transfer, collage, and casein on Masonite, 48 × 32 inches. The Rachofsky Collection. Photo by Kevin Todora.

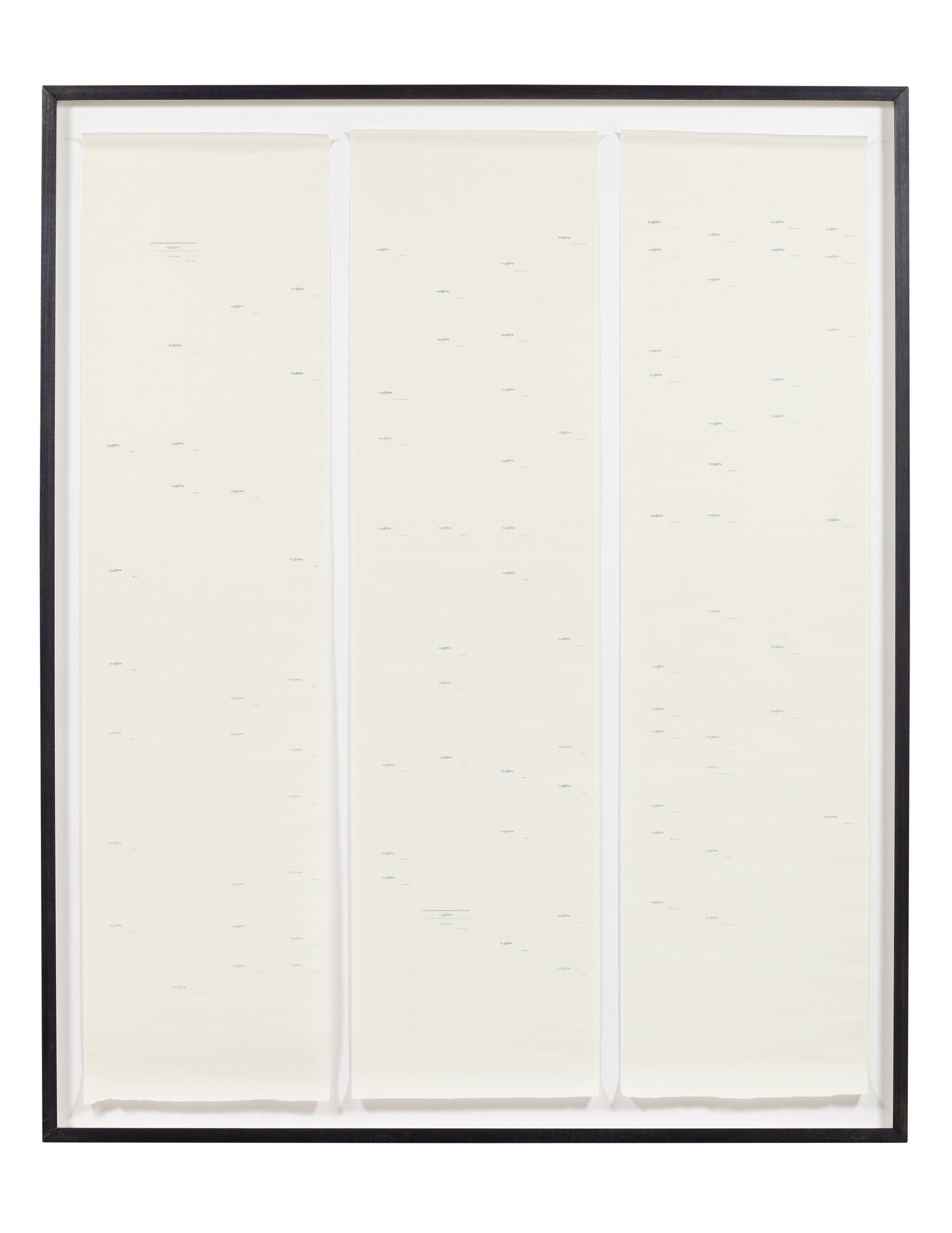

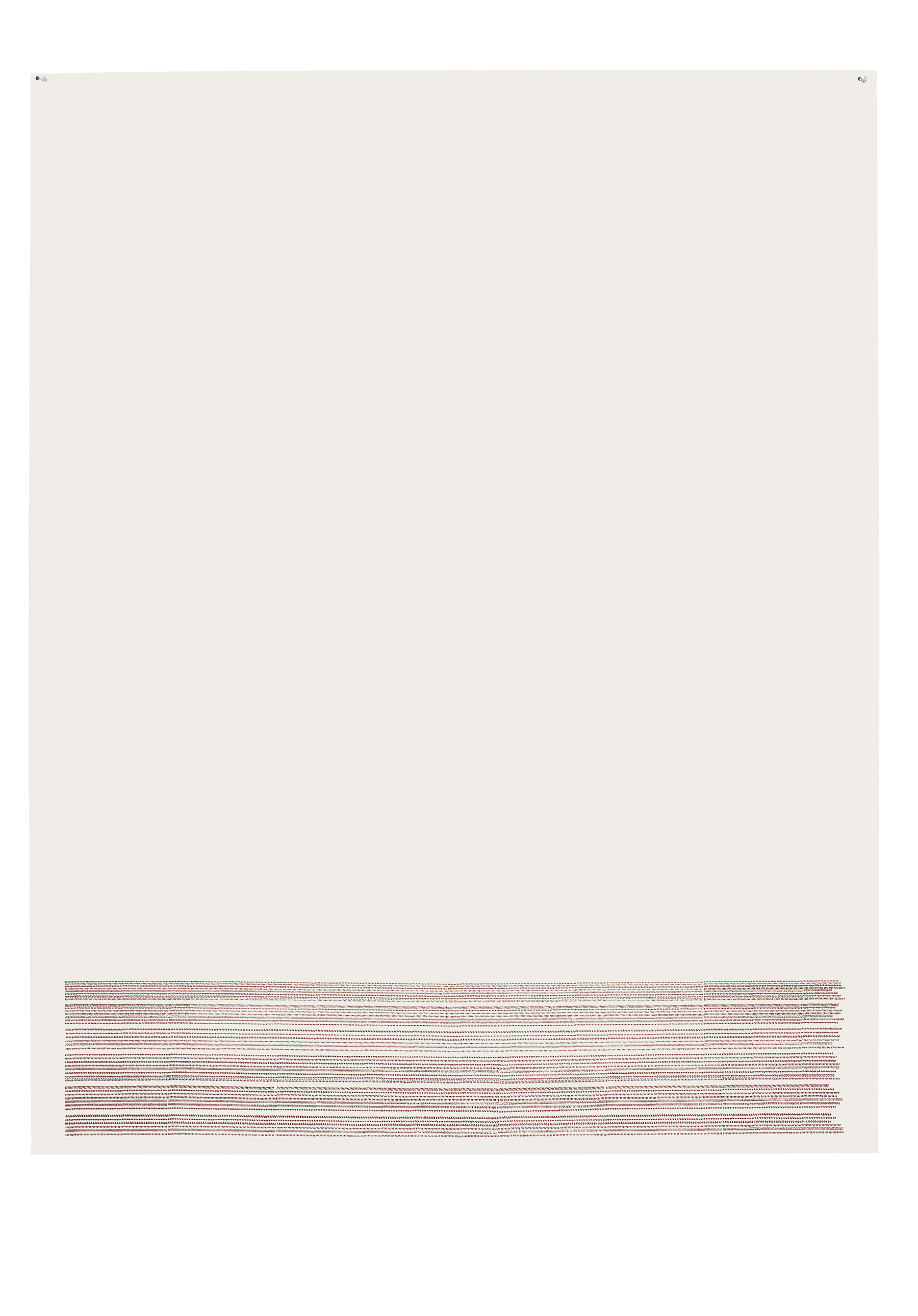

In Erosion’s Fertile Debris (1996), the letters of the titular phrase iterate twice within a brown silt along the bottom of the paper as if settled on a void. In its geologic approach to language, the work nods to Smithson’s ziggurat-shaped drawing of “surd” words, A Heap of Language (1966). For Werther’s Letters (1996), Stark traced only the florid paragraph dividers and dates marking epistolary breaks in a copy of The Sorrows of Young Werther onto three tall, scroll-like sheets of rice paper, paring Goethe down to the rhythm of sections and blank space. In The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1993), Stark carefully reproduced the marginalia found in a secondhand copy of T. S. Eliot’s poem of the same name. In tracing the tracings of one of thousands of previous Eliot students, for instance, Stark replicates a rote approach to the “great white male” canon. Yet if Stark’s transcriptions acknowledge influence, they also subsume it—learning by mirroring, reading through erasure. The radicality of Stark’s text works lies in wasted time, wherein inaction, idleness, repetition, and masturbation constitute neither the incubation of a later explosive expression nor the absence of “the work”—but the work itself. Marginal doodles refuse a masculine, heroic art. In the process, Stark asserts her own voice over those of her material. Not even in the infamous and witty sex chat video My Best Thing (2011) do her semi-anonymous male correspondents challenge or supersede Stark’s authorship. Rather than collaborators, Stark’s male figures remain foils for what she calls “this weird business of exhibitionism.”2

Frances Stark, Werther’s Letters, 1996. Carbon drawing on rice paper. 73 × 64 inches. Collection of Dean Valentine and Amy Adelson, Los Angeles. Photo by Elon Shoenholz.

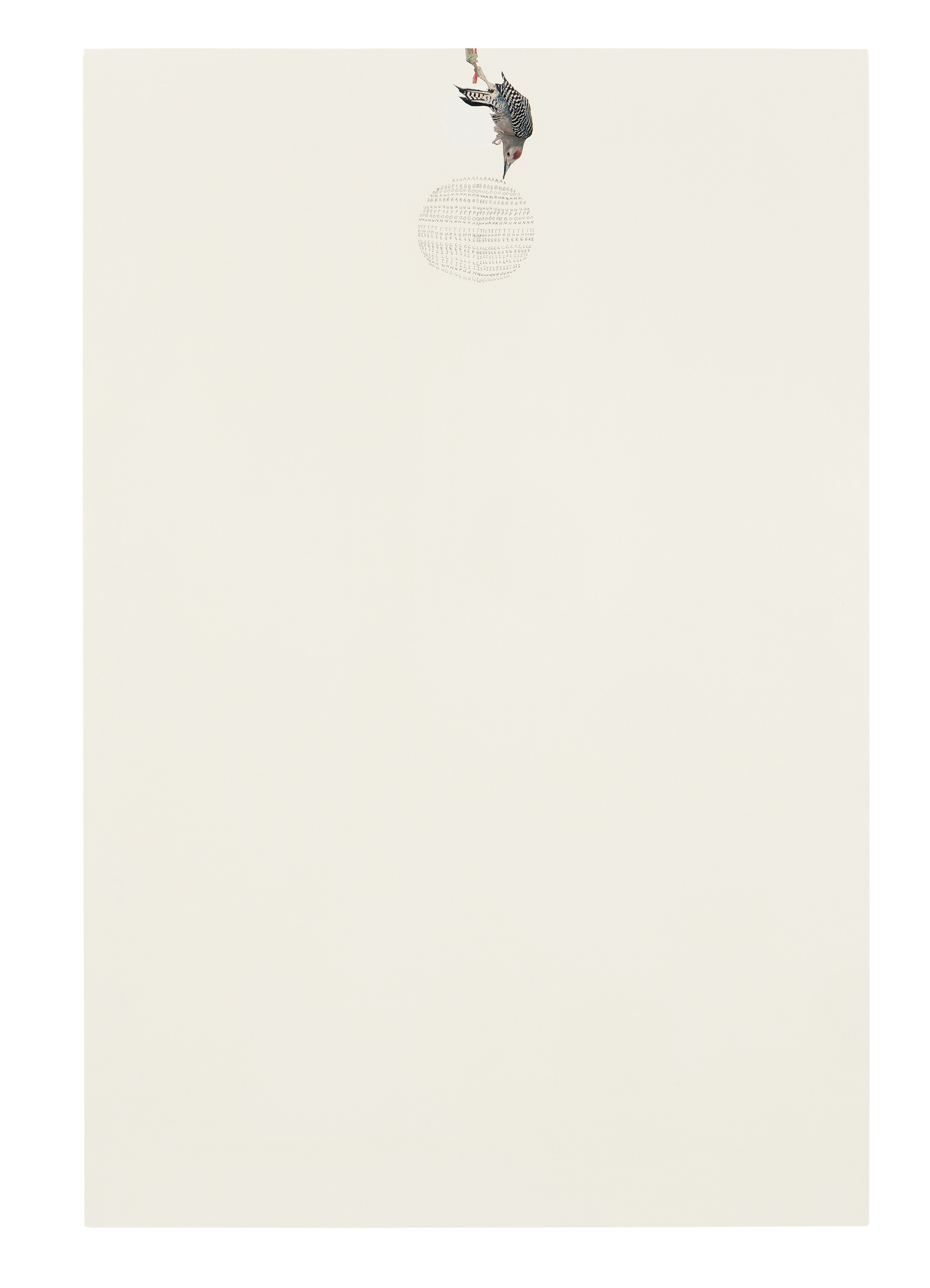

In Frances Stark’s A Bomb (2002), several columns of lowercase letters descend in a ball from the beak of a woodpecker clinging to the paper’s top edge. Each reads: “a bomb upon the ceiling.” The line is from Emily Dickinson’s “These are the Nights that Beetles love” (#1128), and it is a rare citation of a woman author. The cartoonishly round explosive holds fast above several square feet of blank page like a poised, withheld poem. The piece figures, in the Hammer Museum’s comprehensive catalog for the present retrospective, the whimsical concrete layouts (bubbles, hearts, winged diagonals) of the TEXTSCONIUNXIT, an “unsolicited letter” in praise of Stark’s work followed by several solicited ones.3

I suppose I felt doomed to be an artist early on because of the way I drew all over the books that I needed for school, from ancient history to math. I was more interested in drawing in the margins than actually doing the work.

—Nancy Spero, Art21

More than her acknowledged influences, however, the formal and conceptual precursor of Stark’s output of the 1990s is Nancy Spero’s Codex Artaud (1971–73). The Codex comprises 37 framed scrolls of thin paper collaged with typed passages from Antonin Artaud’s writings and embellished with gouaches and prints of hybridized Greco-Roman, Christian, and Egyptian myths. Like Stark’s text drawings, the Codex employs wedges, slabs, and bulges of type, sometimes formed of repeating phrases (see Codex Artaud VII), composed against swaths of empty space. Like Stark, Spero envelops the masculine voice in a feminine artist’s language: for both artists, the subjectively hermeneutic, physically fragile, pathologically concentrated artwork is itself a point of feminist resistance. As with Spero’s previous Artaud Paintings and War series, the Codex bears out her conscientious refusal of the heroic masculine media of oil paint and canvas, turning instead to the stain-like forms of gouache and india ink. So too does the fact of using “another’s” voice contradict both the expressive mandate of Abstract Expressionism and the austerity of Minimalism.4

Yet if Stark cites and copies her sources, Spero’s is a more entangled engagement. As Christopher Lyon writes, mythology and the scroll form served Spero’s desire “to put history into art and to put herself and other women into history. To be present in history meant, for Spero, to speak—for her voice and the voices of all women to be heard.”5

Spero depicts a struggle that is not only personal but also national, epochal, and human. According to Spero, only Artaud’s words could match the pain she endured from rheumatoid arthritis—a disease that afflicts far more women than men. Only Artaud’s screeds could figure a scream to counter the powerlessness Spero felt as a woman in the art world of the 1960s and as a US citizen during the Vietnam War. Paradoxically, for Spero, it was the abject masculinity of this voice (at times its outright misogyny) that could express the extent of her—and our—alienation. Artaud enters a dialogue with Spero—sometimes overtaking her, sometimes serving her, always providing her his voice.

Artaud: Woman as whore. Dare I say, he screams in his partial guise as a woman?6

−Nancy Spero

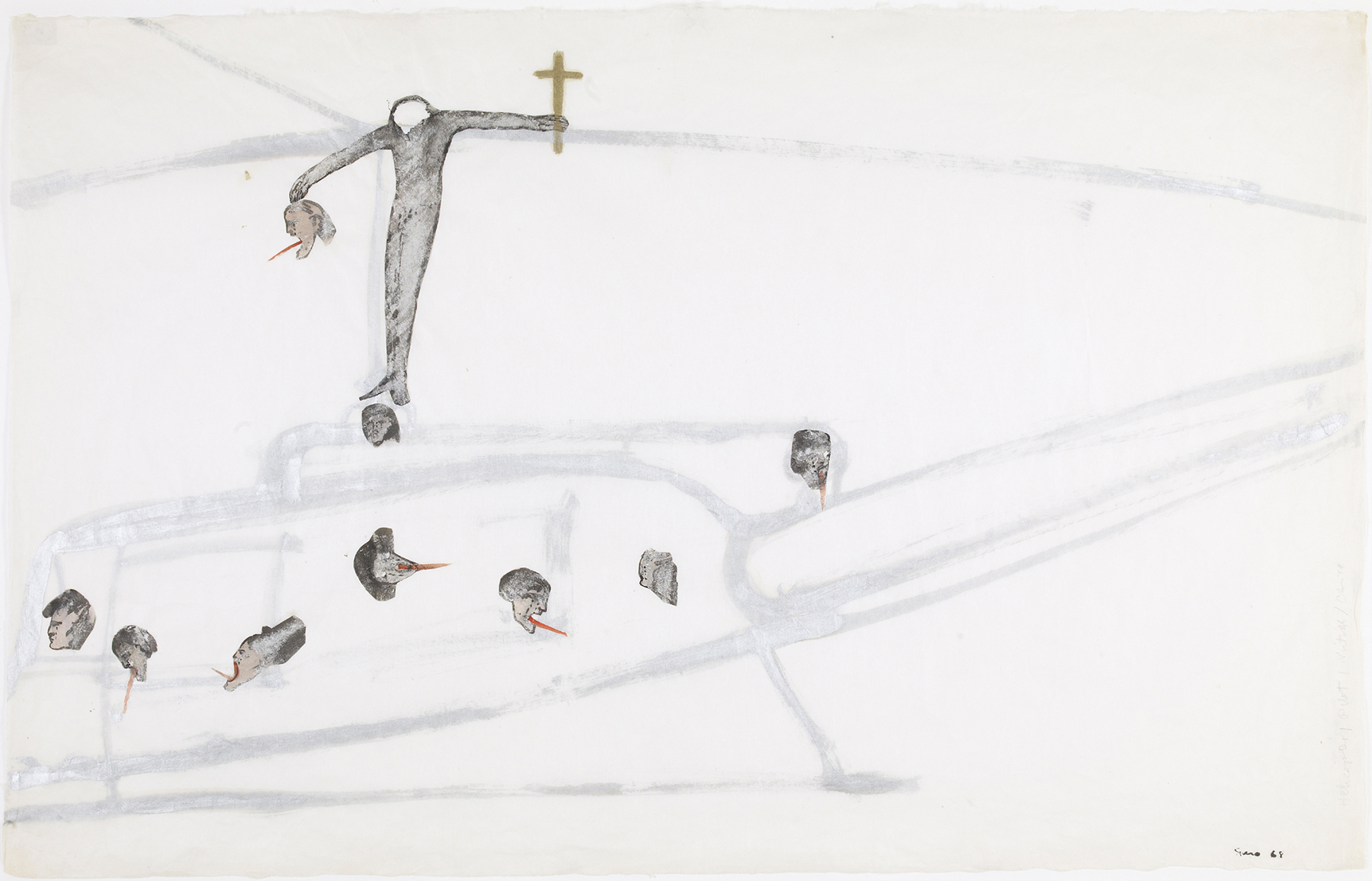

The Codex builds on the more explicit military imagery of her anti-Vietnam War gouaches. A selection of titles hints at their hairy, watery, open-mouthed violence: Swastika and Victims (1968); Helicopter, Pilot, Victims, Christ (1968); Androgynous Bomb and Victims (1966); Christ and Eagle (1968); Christ and the Bomb (1967); Bomb Shitting (1966). If Artaud is made to speak for Spero and for “all women” in the Codex, in the War series Spero spoke for the disenfranchised, the persecuted, the murdered, and the disappeared, from Artaud to the Vietnamese to the Sabine women. The recurring image of Christ, either crucified from a Skycrane’s winch or on a Chinook’s rotor, represents both the killers and the killed, the bomb and the victim—a sacrificial payload and a crusade. Spero’s archetype of the Victim appears throughout the Codex and War series—a severed or embodied head, always screaming, sometimes with tongue, phallic and on fire. Artaud was himself an outcast—insane, unknown, powerless, and abject. Thus Lyon is able to observe a social marginalization reflected in Spero’s sparse compositions. The figures hold off negative space, hugging the scrolls’ edges, “in the classical Greek tradition of placing images of Greeks battling their ‘Others’—Amazons, Centaurs, and barbarians—in metopes and friezes at the margins of their sacred architecture.”7 Spero merges the address of the victim with the victor’s aesthetic: the Greeks felt beset by outside forces—but it’s the victor that carves the frieze. In Spero’s hands, the empty page is a formal iniquity.

I’m gonna take the fingers off of her hands.

−Pink Fairies, “War Girl”

Frances Stark, Untitled (Tropic of Cancer), 1993. Paperback books with drawing paper and carbon between each page, two parts, 7 × 5 inches each. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne.

The combinations in the Codex and the War series of male and female signifiers predate Spero’s decision in 1974 to use only female figures and, when representing men, to do so through images of women.8 Her “female” helicopters screech like harpies, while their blades jut out “like penises.” Says Spero, “It was male power destructively thrashing about.”9 Yet “females, as has been noted, are the mothers of monsters. Women can nurture warriors or foist aggression.”10 Hence in the War paintings Spero gives her atomic mushroom clouds female or male features—breasts spewing blood or heads on phallic stalks—and sometimes both.11 Spero also conflates the Capitoline wolf and Nut, as in Codex Artaud VI, where a disembodied victim suckles not at the bent figure’s breasts, but at its penis, and in the War drawings, sometimes transposing the features of both onto helicopters, as in S.U.P.E.R.P.A.C.I.F.I.C.A.T.I.O.N. (1967), where gory victims dangle from a grinning she-copter’s row of teats. Spero represents womanhood as at once maternal, sexual, and violent.12 Codex Artaud and the War series make use of two mythological mother-forms: The Roman she-wolf (Capitoline Wolf), who nursed the twins Romulus and Remus, and Nut, the Egyptian sky goddess who arches over the earth in a dress of stars. In a perpetual, life-giving subsumption, the latter swallows the sun god Ra each night and births him each morning. The former is classically depicted as both predatory and defensive, snarling and alert as she nurses her heedless human children. Romulus would found a bloodthirsty empire after killing his twin. In another episode of Rome’s founding myth, the young city, teeming with displaced and unmarried men, perpetrates the rape of the Sabine women. Yet these women soon bear their abductors’ children; as the mothers of new Romans, they plead with their fathers and brothers to end the war.

Frances Stark, Erosion’s Fertile Debris, 1999. Carbon on paper, 77 × 60 inches. La Colección Jumex, Mexico. Photo by Francisco Kochen.

Christ, therefore, does not in the beginning consider himself as something special. He just is as he is. Why is not everybody else that way?13

−Wilhelm Reich, The Murder of Christ

For Spero’s martial eagles and lactating Hueys trade Stark’s aviary of songbirds, woodpeckers, and peacocks. The birds pun on Stark’s name to serve as avatars. See, for example, Portrait of the Artist as a Full-on Bird (2004), a picture of a parakeet on a branch of collaged text. In Agonizing yet Blissful (2001), a cutout of a butterfly in chrysalis provides the leaf on an apple of words in red marker: “AGONIZING YET BLISSFUL LITTLE ORGIES OF SOUL PROBING.” Her collage Get on the fucking block and fuck. Or don’t (2008) is a diptych of two peacocks—vain, decorative, and male—their tails formed by bright cutout letters that spell the titular line from Henry Miller. One panel, text and all, mirrors the other. Indeed, narcissism is not self-love per se, but love of one’s own image. “She is blatantly narcissistic,” writes Ali Subotnick, the exhibition’s curator, “but she owns her self-obsession.”14

Far from the imperialist sex perpetrated, metaphorically and otherwise, in Vietnam and in the Middle East, sex in Stark’s work ricochets inwards.15 Stark’s A Bomb casts the artist as woodpecker, spitting out a concrete drop of text like the formal echo of a drooping teat. In Roman myth, a woodpecker in a fig tree brought food for Romulus and Remus, taking up where the she-wolf left off. Subotnick calls Stark “burdened by a deep need to communicate to her readers and viewers.”16 Yet rather than nourish, exactly, Stark’s references fill time and space—communication for its own sake. Introducing the Hammer exhibition on an exterior wall is Non-Electrical Telephony and/or Lovers’ Telephone (2010), a mural of a tin-can phone; both ends are decorated with peacocks.

TOULON: So what do we tell the Americans about Vietnam?

GALLIMARD: Tell them there’s a natural affinity between the West and the Orient.

TOULON: And that you speak from experience?

−Henry Hwang, M. Butterfly

Without decentering herself, Stark’s insular meditations turned outward for 2013’s video installation Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater b/w Reading the Book of David and/or Paying Attention Is Free, presented for Uh-Oh in the Hammer’s video gallery. In all, the piece makes a fraught comparison between Stark’s own struggles with the administration at the University of Southern California, where she was a tenured professor in the graduate fine arts department, and the “University of South Central,” the gang-menaced working-class neighborhood two miles south of USC’s campus.

Nancy Spero, Female Bomb, 1966. Gouache and ink on paper, 37½ x 309⁄10 inches. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Image courtesy Galerie Lelong.

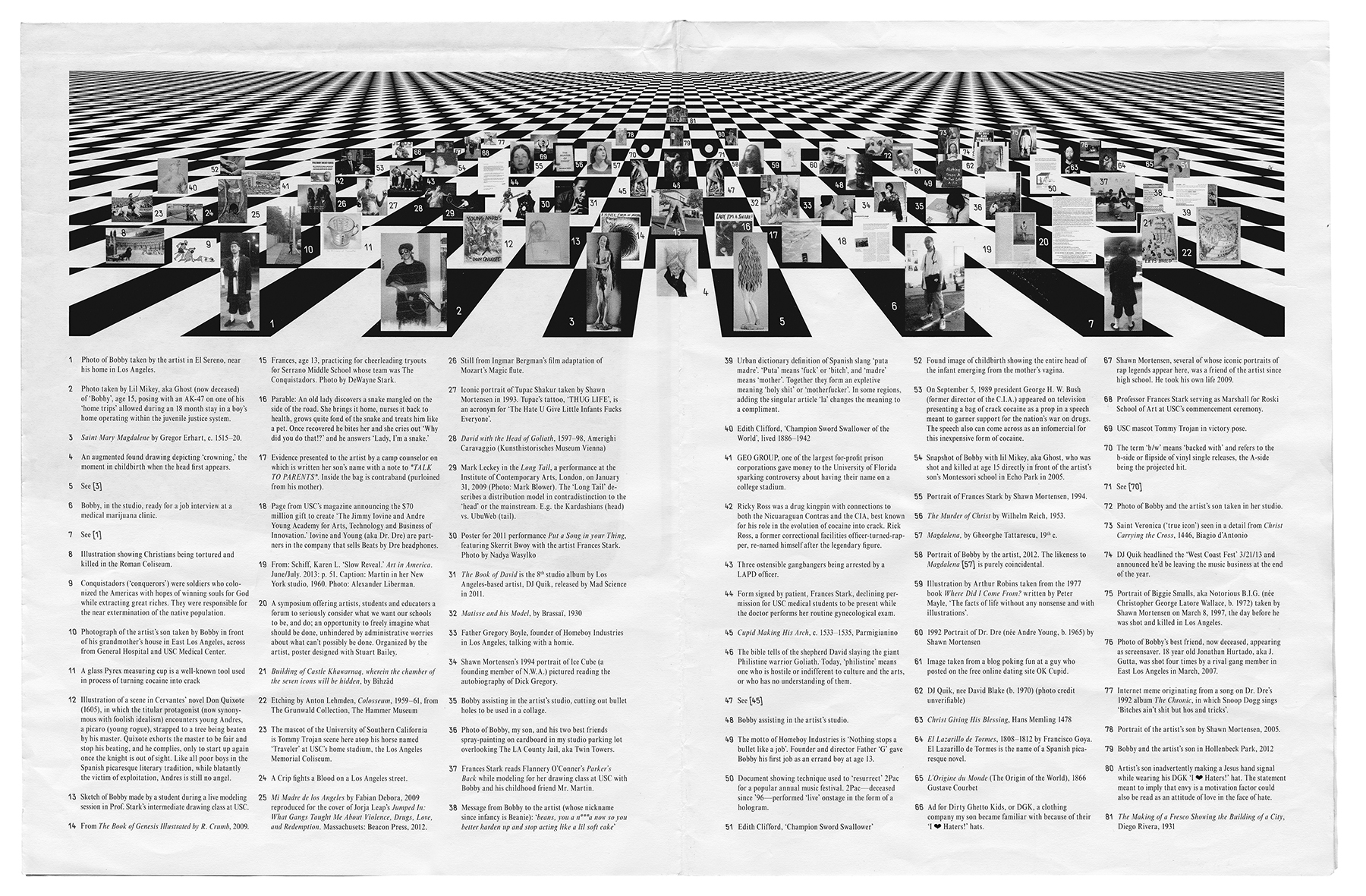

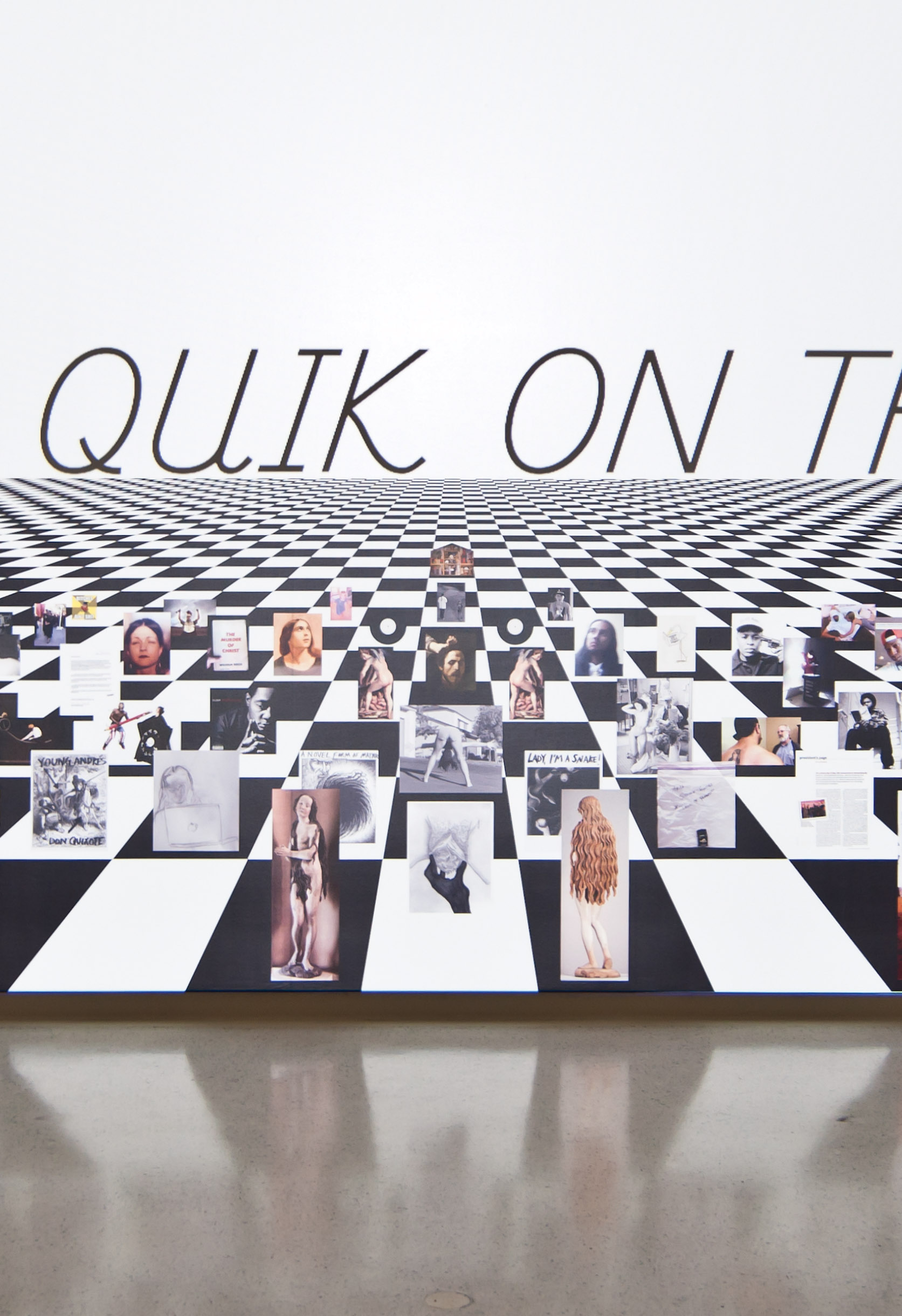

(Beyond this project, the artist has been an outspoken critic of the university’s move to sideline its highly regarded MFA program in favor of the more marketable, entertainment-based approach prompted by a large donation from producers Jimmy Iovine and Andre Young, aka Dr. Dre.) The installation’s soundtrack, samples from DJ Quik’s “Catch-22” and “Fire and Brimstone,” sets Stark’s conflation of academic conflict and gang violence to the hypersexual beat of battle rap.17 A printed backdrop of personal and art-historical images spread out like a ziggurat or sidewalk memorial on a chessboard, receding in classical perspective; all are heavily footnoted in an accompanying publication and takeaway posters. A second text by Stark, flashed into the “sky” above the chessboard, riffs not only on DJ Quik but her friend and muse, a young Chicano from East Los Angeles nicknamed Bobby Jesus.

Nancy Spero, Helicopter, Pilot, Victim, Christ,, 1968. Gouache and ink on paper, 27½ × 42¼ inches. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Image courtesy Galerie Lelong.

From this initial juxtaposition follows a dense collage of associations, from motherhood to artistic production, from the USC Trojan mascot to Los Angeles gangbangers. Image #31 depicts the cover of DJ Quik’s The Book of David, named for the Biblical prophet, adulterer, and psalmist. Image #11, a Pyrex measuring cup of the sort popular with crack manufacturers, provides a formal echo of the Roman Colosseum, which appears both in #8 and #22—the latter a suggestively lipped and folded etching by Anton Lehmden of the Colosseum in ruins. A comparison to Spero’s Vietnam may seem extreme; yet Stark intimates a war as well: an attack by a nation on its own marginalized populations—or what Paul Virilio would call endo-colonialism.18

Played out, these metaphors figure something like gladiatorial blood sport between young men of color in the arena of the artist’s vagina, to the amusement of the ruling class (perhaps USC’s board of trustees).

And masturbation might be the best example of working with what is at hand.

−Howard Singerman, “Frances Stark at the Rim”

The idiosyncratic argument here is at times alienating and always forceful: all roads lead to Stark. Alma mater, Stark points out, is Latin for nourishing mother. Both mother and artist share a creative capacity, while Stark, once the student of Eliot et al., has become the pedagogue. Other images include #65, Gustave Courbet’s L’origine du Monde (1866)—the “ultimate” motherhood, depicted (by a man) as upscale pornography—and #44: a form in which Stark denies permission for USC medical students to be present at her gynecological exam.

Frances Stark, Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater b/w Reading the Book of David and/or Paying Attention Is Free, 2013 (take-away offset poster). Multichannel projection with sound, inkjet mural, and takeaway offset posters, 7:20 min. Purchased jointly by Museum Contemporary Art Chicago with funds provided by Marshall Field’s by exchange and Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Installation view, Carnegie International, 2013. Image courtesy Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Conley

From the moment in My Best Thing when Stark tells her partner that she has a child to her comparisons of art making and giving birth to the innuendos of Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater and related drawings, Stark presents herself as the figure of the sexual mother. While Spero provocatively returns motherhood to the ancient mix of sex and death, Stark’s work centralizes the myth of the MILF. Deferring, for a moment, questions of representation and privilege, it is the ambiguity of her relationship with Bobby Jesus—whom she characterizes as student, muse, son, and lover—that approaches taboo. Artist is to muse as mother is to son—biological or no. Stark’s son also features in Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater. For example, in #80, he is pictured “inadvertently making a Jesus hand signal while wearing his DGK [Dirty Ghetto Kids] ‘I ♥︎ Haters!’ hat.” His naïve interest in hip-hop seemingly props up Stark’s own. In This Is Not Exactly a Cat Video: w/ David Bowie’s “Starman” (2007), Stark’s son and his friend watch a Bowie video playing on a MacBook while providing the artist with an amusing subject: her own “creation.”

I felt very free when I did the series. …I used childish means in doing it. Very simple methods of—I pasted paper together, I used children’s paint, scissors. …But, I think, with kind of the most excruciating thoughts.

−Nancy Spero, in Nancy Spero by Patsy Scala

Motherhood has not cancelled the seductive poses of Total Performance; rather, a more nuanced “totally performed” femininity marks the most recent phase of Stark’s work, in which she has sought out a series of male muses. The dancehall hype man Skerrit Bwoy daggered her on stage as part of the talk Put a Song in your Thing (2011) at Performa (the poster, with Skerrit Bwoy in American flag pants waving the eraser of a giant pencil in Stark’s enraptured face, is #30).19 DJ Quik’s music, words, and life story guide the exegesis of Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater. More recently, Stark sought Quik’s collaboration on a version of The Magic Flute; he turned her down. Stark’s latest works project her notions of race, class, sex, art, and pedagogy onto the figure of Bobby Jesus. The nickname “Jesus,” given to him by Stark, is itself an overburdened euphemism for Stark’s personal mythology. For Stark, the idea of (Bobby) Jesus mostly shores up her own role as Holy Mother to his Son; in the lyrics of Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater, the artist also casts herself as Magdalene, Christ’s would-be seductress.

Frances Stark, Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater b/w Reading the Book of David and/or Paying Attention Is Free, 2013 (detail). Multichannel projection with sound, inkjet mural, and takeaway offset posters, 7:20 min. Purchased jointly by Museum Contemporary Art Chicago with funds provided by Marshall Field’s by exchange and Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Installation view, Carnegie International, 2013. Image courtesy Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Conley.

The strategy and stance of Jesus was consistent in that it was always out of step with the world. Jesus defied all the categories upon which the world insisted: good-evil, success-failure, pure-impure. Surely, He was an equal-opportunity “pisser-off-er” in this regard.20

−Father Gregory Boyle, Tattoos on the Heart

Frances Stark, Get on the fucking block and fuck. Or don’t, 2008. Vinyl paint, collage on rice paper backed with Mylar, diptych, 72 13⁄16 × 37 13⁄16 inches each. Collection of Eleanor Heyman Propp, New York. Image courtesy of Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne.

Thus the figure of Christ conflates power and sex. Stark notes of #58, a pictorial portrait of Bobby Jesus, “The likeness to Magdalena [57] is purely coincidental.” Stark neither confirms nor denies the two are lovers.21 Yet even if, to all appearances, Bobby Jesus remains the desirable but asexual, spiritual bridegroom, the cross-gendered softening of the long-haired Bobby as muse is no accident.22 In the front row of the BJAM backdrop, flanking a drawing of a baby crowning, Gregor Erhart’s sixteenth century statue of a contrapposto Magdalena (#3 and #5)—the original holy whore—insinuates Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. On either side are two photos of Bobby Jesus, pictured recto and verso. Stark compares herself to “whatever the female term for womanizer is.”23 In this, Stark acknowledges the sexism of the English language—in which cougar is probably the closest feminine corollary to the male predatory wolf, yet carries (like the she-wolf) a derogatory sense of age, even maternity. At the same time, subsuming the colonialist paradigm, Stark adopts the role of active patron and protector to Bobby’s infantilized, kept passivity—an inverted and inward domination, but domination still. “People have suggested that it’s exploitative,” Stark told T Magazine. “But he’s aware of what he’s doing. And he wants to be a star.”24

Frances Stark, Behold Man!, 2013. Inkjet prints and paint on panel, 75½ × 96⅛ inches. Courtesy of the artist and greengrassi, London. Photo by Brian Forrest.

They cannot represent themselves; they must be represented.

−Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (epigraph to Edward Said, Orientalism)

In interpreting such boldly personal work, it’s difficult to follow Brad Phillips’s entreaty to “forget what the artist looks like, forget how old they are, forget what’s being said about them, and who says it. Look at what they are making.”25

The 2013 collage titled Behold Man!—the phrase with which Pontius Pilate indicates the humiliated Jesus in the art historical Passion—depicts a studio strewn and hung with images of male nudes and semi-nudes. Yet it is Stark, spread out on a couch like the odalisque, Sharpie at her lips, her inviting/daring eyelock mirrored by that of a lamp shaped like a rooster (or cock) at her head, who gazes straight out from the composition’s center. It’s difficult to forget the artist when the work states, again and again, Ecce Homo—with Stark as both Pilate and Christ. Stark’s project is less like the intertwining voices of Spero and Artaud than a kind of ventriloquism. Bobby Jesus doesn’t speak for Stark; Stark speaks for, and as, Bobby Jesus.

Frances Stark, Clever/Stupid Pirouette, 2014. Sumi ink on Arches paper with inlay, 6213⁄16 × 45½ inches. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buxhholz, Berlin/Cologne

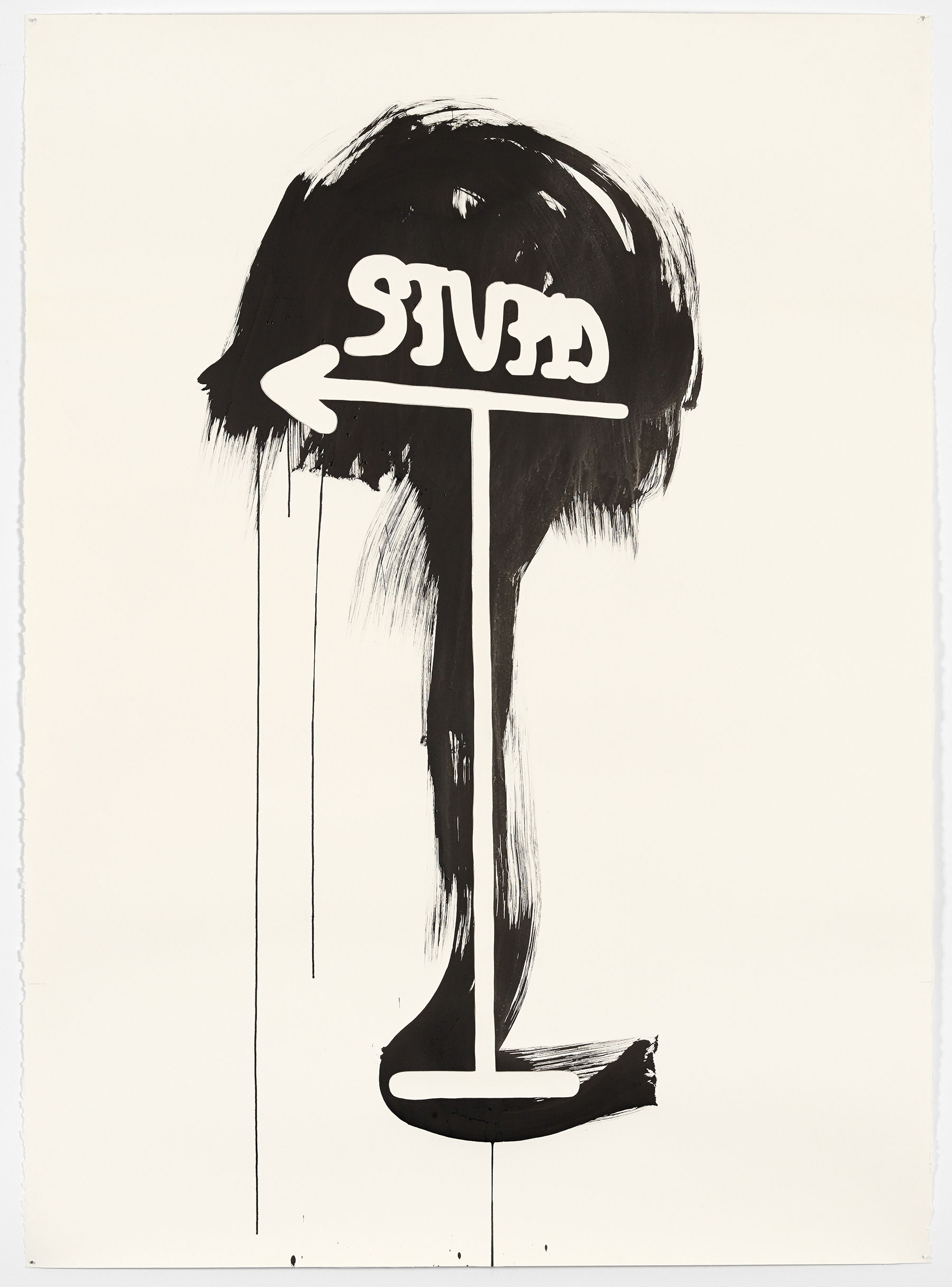

Like a sexed-up endo-Orientalist romance, Stark’s textual travels to the land of hip-hop and gangs remain an outsider’s discourse. The self-deprecating yet exhibitionist ambivalence with which Stark presents her own practice extends to her treatment of her subjects. In Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater, Stark lumps a wide range of “otherness”—racial, sexual, classist—into some idea of the Street, with which she claims to be personally familiar, while redirecting these charged considerations inward in the same narcissistic fashion with which she treats, in the collage In-Box (2004), the junk mail that shows up at her studio. Stark’s Clever/Stupid Pirouette (2014) is a sign that reads “clever” on one side, “stupid” on the other (black on white backed with white on black). Stark’s, spinning binaries restate, evasively, “The personal is political.” Where Chatroulette and Instagram appear to open up the studio, to interconnect the alienated and the silenced, they provide something merely resembling the social.

And it was in the context of endless comparisons of the plight of “women” and “blacks” that they revealed their racism. In most cases, this racism was an unconscious, unacknowledged aspect of their thought, suppressed by their narcissism…

−bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman

“There is a tiresome ambiguity to the work,” writes Morgan Quaintance, in a review of Stark’s Bobby Jesus-era solo show at greengrassi (Sorry for the Wait, 2015), “tiresome because a perpetual loop is set up between empowerment and objectification, depth and surface; neither angle is presented as more valid than the other.”26 Art is often ambiguous; the problem, more precisely, lies with Stark’s ambivalence. Stark’s insecurity, outspokenness, generosity, narcissism, pedagogy, appetites, fascinations, and obsessions are often cited as both acknowledged sins and unapologetic virtues of her work. This much is, per the title of her collected writings, “an honest articulation of the workings of the mind”—articulated, if not examined. Narcissism may be a rich method. It may open the radically anti-productive possibilities of avoidance and gaps. But narcissism is not a valid apology for a sociocultural blindness to privilege and power that figures an oppression of its own.27 bell hooks puts it simply: “The social status of white women in American has never been like that of black women or men.”28 For hooks, it is precisely the white feminists’ narcissism that leaves the racism of their thought “unconscious, unacknowledged.”29 It makes Stark no less white when, in #38, she provides a screenshot of a text from Bobby Jesus: “Beans, you a n***a now…”30 Within this sort of self-misrecognition, it’s not A Bomb exactly—the droplet of Dickinson pending from the woodpecker’s beak—but Stupid/Clever on its stand, loosely inked with a loaded black brush, an abstract expressionist mushroom on a dripping stalk that recalls, likely by accident, one of Spero’s hermaphrodite bombs.

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He serves on the editorial board of X-TRA.