On my first visit to the Blinky Palermo retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA),1 I had just begun to look at the much-anticipated show when the lights in the museum went out. For a minute or two, those of us in the galleries couldn’t see. This seemed a fitting beginning for an encounter with an enigmatic artist who consistently “shunned public discussion of his practice and ideas.”2 I had little firsthand experience with Palermo’s work. Except for the paintings in the Dia Art Foundation collection, his work is rarely exhibited in North America. But much has been written about Palermo: he was born in Germany under the name Peter Schwarze, but later renamed, by his friend and mentor Joseph Beuys, after the mobster and boxing promoter Frank “Blinky” Palermo; he was intrigued by American art and culture and moved to New York in 1973; he died unexpectedly a few years later, at the age of thirty-four. Being in the darkened gallery that evening allowed me to forget the information I had acquired about Palermo and his work; my vision was cleared for a moment and I entered the exhibition fresh, as though what had come before was erased.

Fresh is a good word to describe the paintings I encountered. They are very much of the time in which they were made, yet unanchored, and still relevant to dialogues around painting today. The reception of artwork depends heavily on our knowledge of the cultural conditions of its time, and as time passes, we are often left with the artwork as historical artifact; it ceases to operate outside of those discursive conditions. Palermo’s work acknowledges painting’s intrinsic physical elements and its limitations as it relates to site, materials, color, scale, and history. This allows for the work to move in unexpected ways.

While it is important to think about Palermo’s work in the context of the history of painting, a great deal can be derived from looking closely at the work itself, in person. The thoughtful installation at LACMA gives us a chance to do that. The exhibition is spacious, thus we are given room to take it in. There are no large, didactic panels telling us about the artist, and the title cards are hung in the doorways between galleries. Enough of an idea about the dates and materials of the work is provided without interfering with our visual experience. Each gallery is primarily devoted to a particular group of works, with some overlapping of bodies of work. This overlap alludes to the fact that Palermo worked simultaneously on multiple bodies of work. The installation moves through the early paintings and assemblage pieces, to the Cloth Pictures, the Wall Drawings and Paintings, and ends with the Metal Pictures.

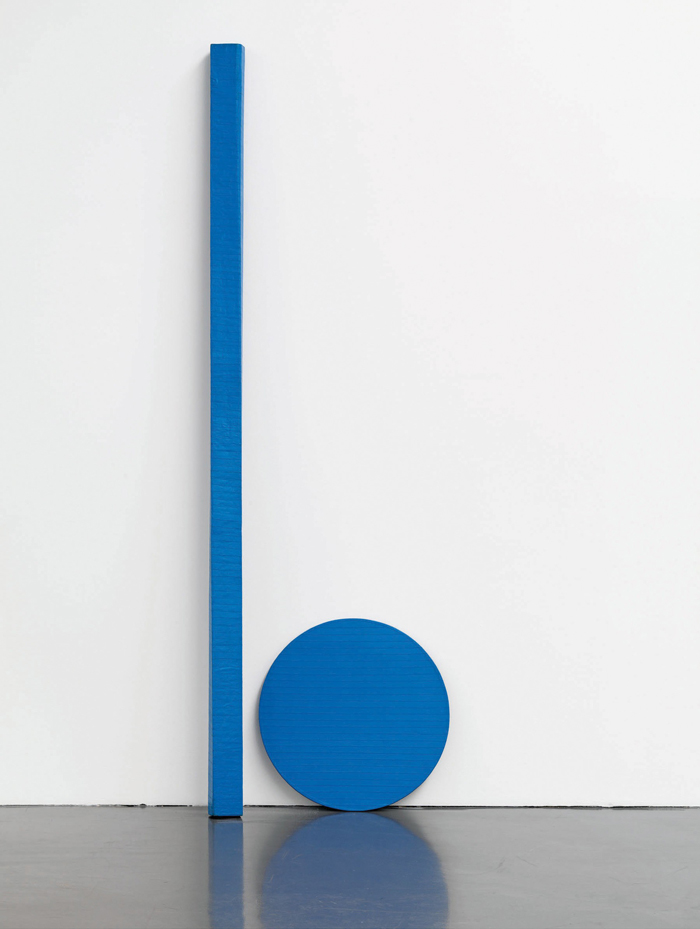

Blinky Palermo, Blaue Scheibe und Stab (Blue Disk and Staff ), 1968. Fabric tape on wood. Staff top: 99 x 3.96 x 2.95 in.; staff bottom: 99 x 4.1 x 3.14 in.; disk: 25 x .51 in. Private collection, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

The exhibition is installed chronologically, which allows an idea of Palermo’s process to form. A narrative of working out a specific set of ideas and a coalescing of those ideas is evidenced. His investigation consists of paring down materials, while identifying over and over again what a painting might be. From one piece to the next the objects seem to repeat “this is that but not that” and “this is a painting but not a painting.” In Blaue Scheibe und Stab (Blue Disk and Staff) (1968), for example, two pieces of wood—a round flat piece and a long rectangular one—are wrapped in blue tape. The tape suggests paint but is not paint; the circle is the same material as the staff but not the staff; and the two together are an abstract composition but also two chunks of wood with tape on them leaning against the wall. This cataloging of sameness and difference brings us full circle.

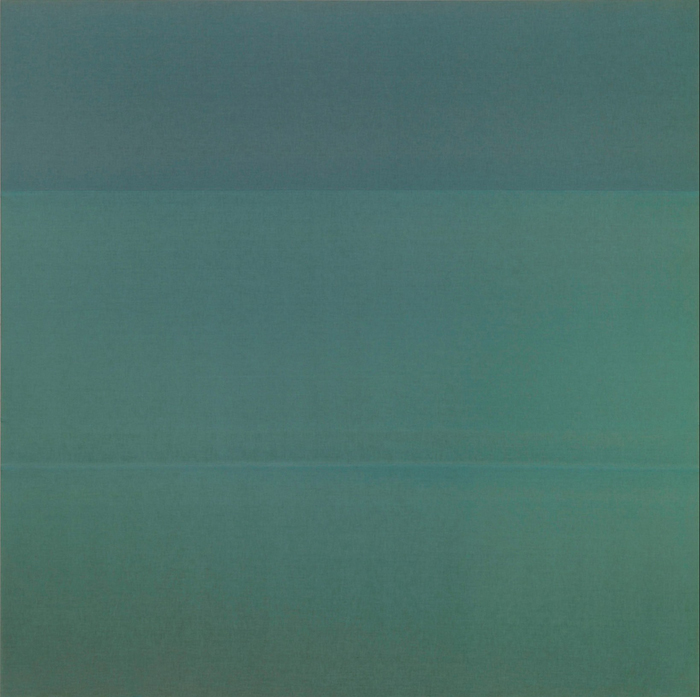

Blinky Palermo, Untitled, 1968. Cotton fabric, 78 3/4 x 78 3/4 in. Collection Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxembourg. Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

The material choices in each piece are simple, yet at the same time subtle details suggest a considered and orchestrated complexity in the making. In Untitled (1968), the deliberate choice of fabric as a stand-in for paint, along with an absurdist nod to the faction of abstract expressionism that used opticality to evince a transcendental experience, is clear. But the places where the cloth overlaps to create small, barely perceptible stripes, beside the even smaller edges where the fabric is stitched, present something quite different. These incidents speak to a quiet contemplation in the actualizing of the object. Another example might be Untitled (1973), where what appears to be a rather banal grey monochrome on closer inspection reveals a few gorgeous bits of brilliant color. An uncovered swipe of orange on one edge that seems to have been forgotten is redeemed by the same orange painted on the back of the support, which casts a reflection on the wall just behind the bottom corners. Both a knowing humor and material authenticity are central to this work.

I walked through the exhibition with friends, and our inability to identify exactly why we were responding to the work came up in our conversations again and again. While our attempt to explain how an artwork affects us seems almost unavoidable, part of what is so compelling about Palermo’s oeuvre is that I can try to explain the material decisions and the way the work fits into a historical discourse, yet I can’t quite put my finger on why it does what it does when I’m in front of it. It’s much like the fourth moment in Kant’s mathematical sublime “when the viewer realizes that her innate capacity to reason is what drives the desire to encompass an un-encompassable object with an inadequate concept.”3

Palermo’s work is activated primarily by perception. He was aware that the photographs of the Wall Drawings and Paintings were “no substitute for the experience of having encountered the work in situ.”4 It is important to view all of his work in physical proximity; a photograph of one of his paintings operates more as documentation than reproduction. Possibly a precursor to Radical Painting,5 Palermo’s work entertains the idea that “the meaning of the painting is determined in the experience of the painting by the viewer. The presence of the painting as an object is always a presence with.”6

Blinky Palermo, Komposition mit 8 roten Rechtecken (Composition with 8 Red Rectangles), 1964. Oil and graphite on canvas. 37 3/4 x 43 3/4 in. Collection 0lga Lina and Stella Liza Knoebel.

Because Palermo refused to speak publicly about his work and thereby clarify his intentions, a critical debate about where his work fits ideologically is ongoing. He has been variously identified as sharing the material concerns of Minimalism, the spiritual concerns of reductive abstract painting, and the theoretical concerns of Conceptual art and Institutional Critique.7 Perhaps Palermo didn’t identify a position so that he could continue to have these seemingly disparate options available to him. He worked in the places between concretized positions, and by extension he gives us the opportunity to grapple with the same contingencies. In this moment when painting often finds itself embattled or all dressed up with nowhere to go, Palermo’s working method is an inspiring example of the way one artist found possibilities of continued engagement.

Judie Bamber is an artist in Los Angeles. She teaches in the Graduate Fine Art Department at Otis College of Art and Design.