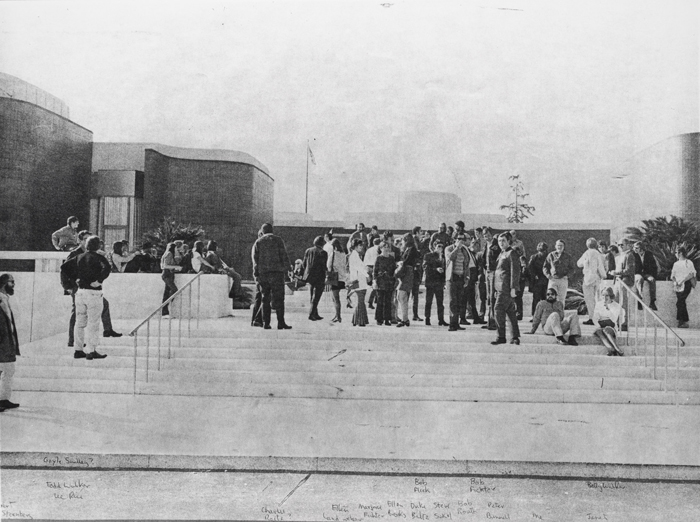

Bill Arnold, Gathering of members outside the Pasadena Art Museum, Society for Photographic Education Annual Meeting, 1973. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography.

There is a large photographic mural in the exhibition The Collectible Moment: Photographs in the Norton Simon Museum. It shows a group of photographers and their students on the steps of the Norton Simon Museum. The photograph was taken in 1973 by Bill Arnold on the occasion of the Society for Photographic Education’s regional conference. The people in the photograph are milling around, talking to one another and waiting for the museum to open. They seem confident and happy, and with good reason–the Pasadena Art Museum, as it was known then, had a photography curator who was actively collecting work by a number of these photographers and their friends.1 It is a celebratory “we have finally arrived” kind of photograph; little did they know how fragile the foundation that they were standing on was.

It seems ironic to me now that this photograph is taken on the steps rather than in the museum itself. In my mind, I imagine that soon after the photograph is shot the museum doors open and everyone turns around and heads towards the entrance. In this scenario I want to yell out for them to hurry, because, with hindsight, I know that the door is not going to remain open long. Not only does Norton Simon take control of the board of directors in 1974, changing the name of the museum and relegating all of these photographs to the storage vault (where most of them stay until this exhibition in 2006), but by the end of the decade the longstanding relationship that photography has to the larger world of art, a kind of parallel universe, collapses. Maybe collapse is the wrong metaphor; a corporate takeover is probably more accurate.

Up until the 1970s, it was almost as if a wall existed in the art world between photographers and everyone else. If you made photographs and called yourself a photographer you were on one side, while if you made paintings, drawings or sculpture (or even photographs) and referred to yourself as an artist, you were on the other. This wall not only separated these people from each another, it made it almost impossible to see what was happening on the other side.

The people in this exhibition were on the side where they called themselves “photographers.” There are exceptions to every generalization and Jerry McMillan and Robert Fichter are two of the exceptions here. It is almost as if they wandered over to the photographers’ side of the wall while it was being built and then couldn’t get back. On the other side, Bruce Nauman, who had a studio basically down the street from the museum, was making photographs. So were Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, Douglas Huebler and William Wegman. All of these “artists” were living in Southern California in the early 1970s, all were producing photographs. But, since they were on the other side of the wall, they are neither in this collection nor in the current exhibition.2

Before about 1975, those artists who made photographs and called themselves photographers had their own galleries, their own magazines, their own departments within museums, often their own curriculum (or even departments) within universities, and their own organizations. It was a community, and my experience of it was that it was a fairly upbeat and supportive one.3 This sense of community was evidenced in the exhibition not only by the photograph by Bill Arnold, where the photographers were hanging out with their students, but by the inclusion of two faculty/student portfolios from the 1970s.4

Unlike like the art world, the photography community wasn’t centered in New York. In fact it wasn’t centered at all. Its activities took place all over the country, mostly around and within university art programs. People helped one another out, brought each other into town to lecture, got each other shows (often organized by the artists themselves) and recommended one another to curators or collectors. In the 1970s, it was the kind of community that sometimes develops when the perception is that not that much is at stake (that was my perception at least). Sure, just like all communities, there were those with more power than others. And, it certainly was a product of its time; meaning it was mostly white, heterosexual and predominately male, but no more so than the rest of the art world. As a community, the closest thing it had to a governing body was the Society for Photographic Education, which was made up mostly of photographers and a few photographic historians who taught in university art programs. The goal of getting an MFA in this system was not so that you could become an art star, or even make a living selling your work, but so that you could get a university teaching job, which is why SPE was so important. Photography was an expanding field in universities at the time so this seemed to make sense, even if in the end it turned out to be a bit like a Ponzi scheme.

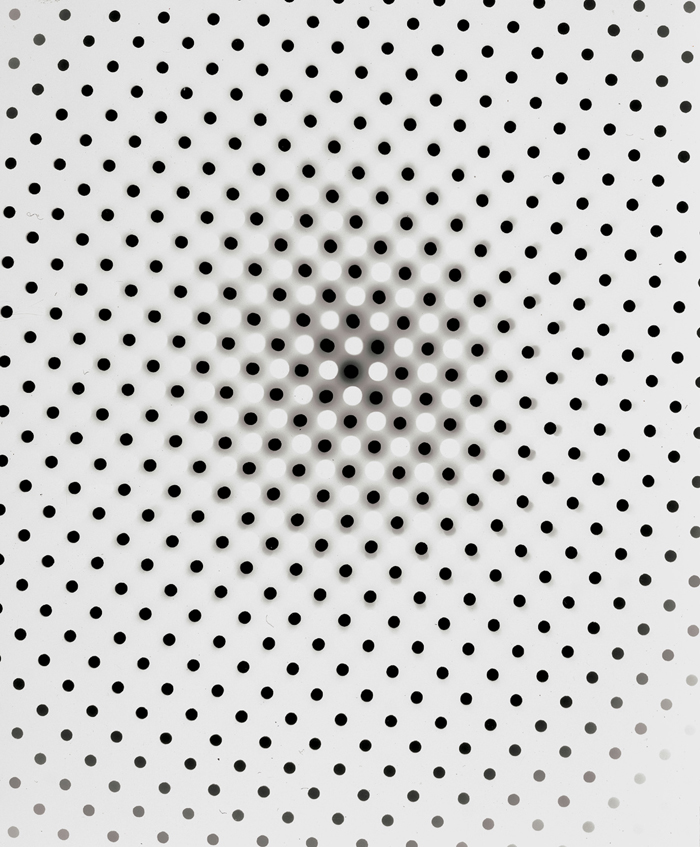

Arthur Siegel, Lucidagram #6837, 1967. Gelatin silver print; Image: 16-7/8 x 14 in. Norton Simon Museum, PH.1969.85. Gift of the artist. © 2006 Estate of Arthur Siegel.

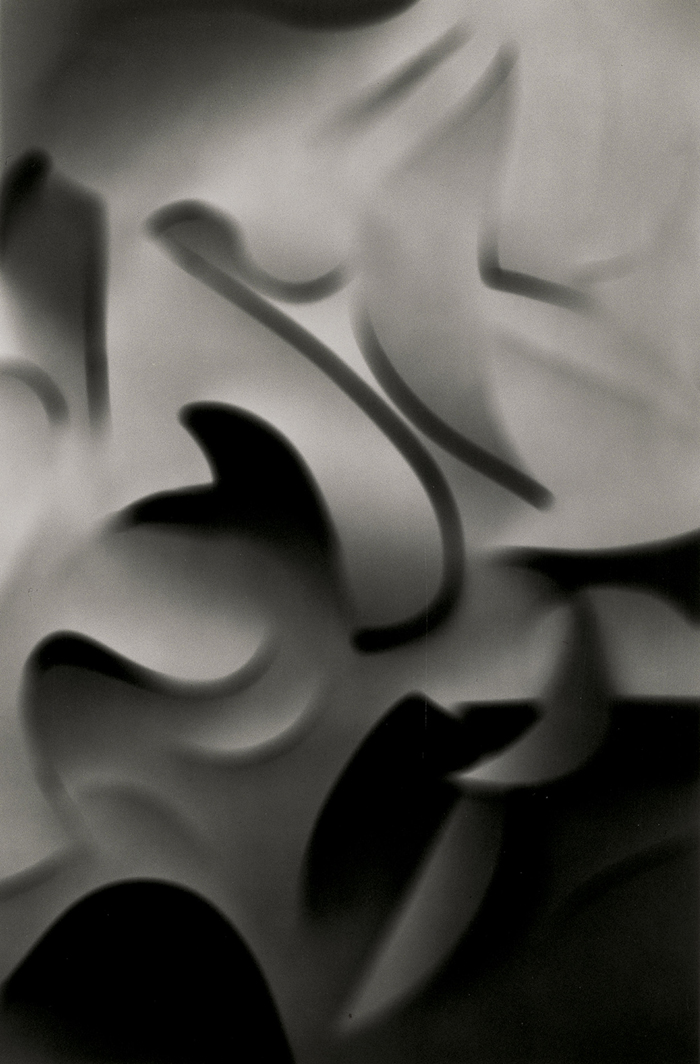

Most of the photographs in this exhibition represent a modernist sensibility (purity of use) or a challenge to that sensibility through alternative processes like solarization, multiple printing and non-silver processes. These works are about being objects, first and foremost, and there are only a couple of things in the show you would even consider referring to as conceptual. The dematerialization of the art object, as Lucy Lippard discusses it, basically doesn’t seem to have started here yet.5 For better or worse, the majority of the works in this show do not shout out for your attention, like so much work today; they simply ask, usually in a very polite way, for your contemplation. The attention to craft is amazing, resulting in prints that draw you to them through the seduction of pure beauty (or its opposite), an approach that had already been called into question on the other side of the wall.

Curator Gloria Williams Sander should be praised for taking on such an ambitious project. However, given the relatively small space allocated to temporary exhibitions at the Norton Simon, more than 75 of the 102 artists included end up being represented by only one artwork. The show is probably most rewarding, therefore, for viewers who bring some prior knowledge about the artists with them. Those photographers with enough images for viewers to get a sense of their project from the show are those who had made names for themselves before 1960, including Edward Weston, Fredrick Sommer, Minor White and Manuel Alvarez Bravo. While this mimics the structure of the Norton Simon’s collection of photography from this period, it is not necessarily the best way to organize a show. If Sander simply had included fewer of these photographers’ works–artists that a museum-going audience are most likely to be familiar with already–the Norton Simon could have shown two or three prints each from more artists working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, making this historical period more legible.

That said, there are many singular works here that reward your attention. Considering the show as a whole, however, I cannot shake the feeling that this is the end of an era. How ironic this seems, given that the smooth narrative of art history tells us that photography is just about to be given its place on stage next to painting and sculpture. There are hints in the show as to where the medium is going–the work of Robert Heinecken, Lewis Baltz, and Diane Arbus being the most obvious examples–but there are not many for a show that includes a over 100 works made after 1965.

Frederick Sommer, Untitled (Cut Paper), 1963. Gelatin silver print; Image: 13-5/16 x 8-13/16 in. Norton Simon Museum, PH.1965.1.25. Gift of the artist. © 2006 Frederick and Frances Sommer Foundation.

Back in the art world, on the other side of the wall, artists like Baldessari and Heubler are making use of the photograph for reasons that have nothing to do with traditional modernist photographic aesthetics. They are more interested in amateur snapshots and movie stills than Edward Weston prints. Their explorations open the door for a whole generation of artists to consider using photography instead of more traditional materials. But, as is so common in corporate takeovers, the larger organization–in this case, the art world–is only interested in the assets of the smaller organization–photography. In other words, only the photographic image is valued, not its personnel or its history. Of the 102 photographers included in this show, probably 75 of them will be unfamiliar to a majority of people that follow contemporary art. And, as is always the case when history is overlooked, later artists produce work very similar to some of the work in this exhibition, and are celebrated for their inventiveness.

Out of curiosity, I compared the list of the 102 artists in this show with the 60 artists in The Last Picture Show: Artists Using Photography, 1960-1982.6 While the two shows obviously do not have a similar premise, they do both contain a significant number of photographs made by artists between 1960 and 1974. What I found was kind of sad; there was absolutely no overlap between the two lists. The wall came down, but it seemed to bury most of the people on the other side.7

One of the most fascinating aspects of the The Collectible Moment exhibition is a feeling of being present for the opening of a time capsule. When it is cracked open, what we find is that art history is more untidy and layered than most institutions can manage to account for, and it involves a lot more people than usually get credit. Now that the Norton Simon has finally let the collection out of the vault, one hopes that they will make better use of it than they have in the recent past. The only two shows that I am aware of that made any use of this collection during the last ten years were the Fredrick Sommer show of 2000 and Lewis Baltz’s Tract House of 2002. While those were both good exhibitions, it would be nice to see the museum recommit some of its resources to expanding this collection. If the Norton Simon commits to a goal as simple as collecting, in depth, the ten photographers from the late 1960s they think are most significant, they could have a collection that does more than merely present a Collectible Moment; they could have a collection that helps explain its importance.

Stephen Berens is an artist and one of the founders of X-TRA.