If globalization, as is so often maintained, problematizes the binary opposition of the national and the international, defying national borders and unhinging dominant cultural paradigms to allow the entry of histories, temporalities, and conditions of production from beyond the West, then why do so many conventional structures remain at exactly those sites that seek to undermine the epistemological and institutional bases of those structures?…While it may not be surprising that the museum has been slow to dismantle these paradigms, why have biennials not done so?

–Elena Filipovic1

The spectatorially and touristically driven “Olympics” of an increasingly globalized art scene, contemporary biennials have promised to serve as “places where a multiplicity of art worlds meet in the presence of a vast, varied…avid, and unpredictable public.”2 This ideological manifesto, applied by Robert Storr to his curation of the 2007 Venice Biennale, included an insistence that the contemporary mega-exhibition is not staged for the “happy few” who share common aesthetic sensibilities and enjoy globetrotting privileges, but rather for a nondescript, non-idealized, fluid viewership whose trajectories through the biennial—and configurations of its significances and meanings—are often unstructured, unrehearsed, and unacademic.3 Storr describes the difficult challenges faced by a mega-exhibition curator: “getting the ambulatory viewer to look at stationary objects without speeding by them in the desire to ‘see it all’ so as to have an opinion about everything.” He also states a goal of “restor[ing] the aura that some have feared art has lost forever but which those who are alert can still summon for themselves in the presence of a unique image or form.”4

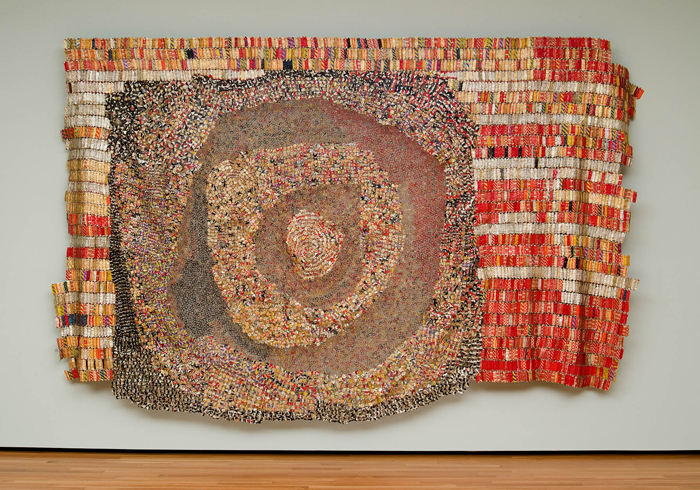

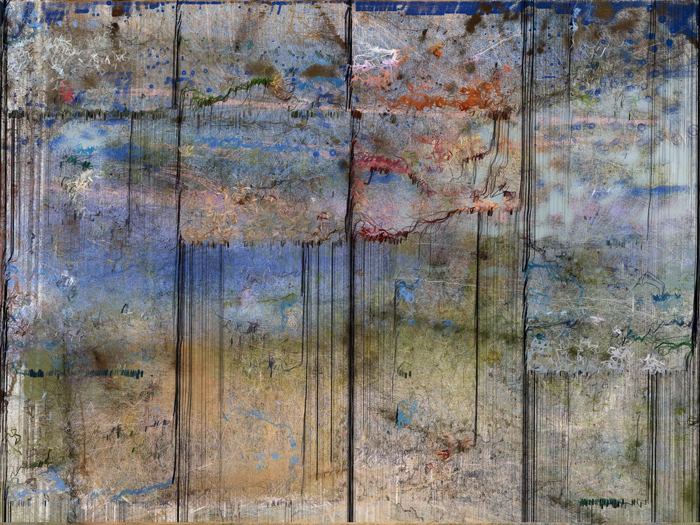

El Anatsui, Dzesi II, 2006. Aluminum liquor bottle caps and copper wire; 117 x 195 x 8 in. Courtesy collection Akron Art Museum. Purchased, by Exchange, with funds from Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. Reed II.

Such yearning for the biennial’s facilitation of “private discovery”5 for the viewer perpetuates and broadens the fantasies of Modernist perception, in which the constancy and situation of the art object stabilize what Storr has called the “intoxicating improbabilities of our imagination and the vivid, often disquieting, actuality of our perceptions.”6 Yet, if Postmodernism heralded the doom of the grand narrative in art, the biennial itself can no longer function as an extension, host, or embodiment of that narrative— immune from the social, cultural, economic, and colonial conditions that alter the nature of equity and access, as well as the primacy of the art object that Storr extols. How may the thematic, spatial, and institutional structures inherent in a biennial’s composition adequately include art practices that openly resist, dismantle, or avoid those structures?

For Storr, such aura-inducing “private discoveries” in the context of biennials—in addition to the genuineness of spectatorship—are consequences of one’s “being there,” but also of art’s visibility and accessibility. As he notes, “To make sense of something for oneself requires that one single it out, but in order to do that it must first be visible.”7 While Storr initially registers his understanding of such visibility as a function of the strategies and techniques employed almost exclusively by Western artists, he concludes by stating paradoxically that the volatility of social norms, cultural practices, political circumstances, and representational inequities that might ultimately influence the nature and extent of art’s visibility do not come into play within the contemporary biennial. Instead, he asserts that biennials are unequivocally liberal, discursive realms that can and do challenge the viability of “mainstream” contemporaneity and that do not estrange underrepresented artistic voices.8

Storr’s characterization of the biennial as a democratized forum for unencumbered display and sociocultural reflection prefaces his discussion of the West as a “has-been” center of power, whose loss of gravitational pull in the art world has been documented frequently within a range of biennials addressing anti-capitalism, post-coloniality, anti-Western sentiment, and frequently marginalized art practices. (Alfons Hug fancifully envisioned the 2006 iteration of the São Paulo Bienal as a “free territory.”) Herein lies the contradiction in Storr’s view of the contemporary biennial: he wishes his mega-exhibition to rekindle the art object’s aura for an individual viewer (and to rely on the Western, Modernist histories of “aura” to inform his esteem of the art object), but he ignores the fact that the aesthetic and perceptual traditions upon which he bases this revitalization are often the least conducive to the cultivation of the broader cultural sensitivities and inclusiveness he ascribes to the contemporary biennial. If only because of its sprawling pavilions and blockbuster budgets, the biennial—in its traditional state—can only be an awkward “Other” to the struggles, conflicts, tensions, and lacks of the world. If the format of the conventional biennial is to survive today’s bleak economic crises and to document faithfully the global happenings that have the potential to tarnish its glitzy luster, it may no longer remain an oasis for the über-platinum frequent flyer. Biennials must renegotiate their current role as elite, declaratory expositions of narrow strands of contemporary expression and become instead malleable, mobile, collaborative, and ephemeral ventures that can just as effectively showcase states of placelessness, migration, and variability.

Despite Storr’s insistence that the contemporary mega-exhibition should embrace once-peripheral cultural centers and should maintain a clear commitment to “dialogue,” his views of artistic plurality and openness are countered by the standard Western commercial interpretation and “biennialization” of centrality and marginality. Is the “dialogue” of which Storr speaks one that perpetuates not only a hyper-visibility of Westernness, but also establishes hierarchies of Westernness that are defined in relationship to one another without regard to non-Western practices? Biennials—which Storr characterizes as largely conceptual enterprises distinct from the commercial tone of art fairs—do continue to rely upon the same mechanisms of late capitalism that ultimately determine inclusions and exclusions of artworks. For example, the “hotness” of commercial art ventures today almost invariably infects supposedly independent curatorial agendas—establishing a flavor of contemporaneity that often surfaces repeatedly in the course of subsequent mega-exhibitions because of its mass appeal or, quite simply, because curators recycle “biennial artists.” In the end, several biennials only reiterate the primacy of a Modernist exhibition format that fails to serve as an effective and impartial mediator of global, local, and “glocal” art practices and interests.9

Perhaps unavoidably, biennials—Venice included— have been meticulously crafted and expertly deployed exercises in structured branding. They are less concerned with an initiation of cross-cultural discourse than they are focused on their ability to compete with and continue established biennial traditions. What biennials must consider, but most often do not, is not simply the fixity of the work of art, but also the effects of its institutionalization. What are the ramifications of an artwork’s inclusion in an exhibition whose scale often precludes effective contextualization of and communication about its significance? What are the ways in which the artwork’s inclusion is often predicated on a financial wherewithal that is not universally shared amongst contemporary practitioners? Finally, what are the consequences of such “biennializing” in locales that are often antithetical to, unaware of, or unburdened by Western art history?

According to a lecture that Storr delivered at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney in July 2008, dialogue within and about the mega-exhibition requires a “roughly equivalent” unfettered access to information about those with whom one is in dialogue.10 Yet, clearly, dialogue involving the nature of the mega-exhibition relies upon the financial ability to participate in its proceedings, whether in the role of artist or viewer, and, according to Storr, to do so on a fairly regular basis. From a critical and curatorial point of view, Storr freely admits that such globe-trotting is a privilege afforded to the very few and that he is, unabashedly, one of these. Nevertheless, such recreational, aesthetic, and viewerly privileges not only threaten to characterize the nature of biennials and mega-exhibition scholarship as decidedly bourgeois, but also frequently serve as one of a host of impediments that stymie or altogether prevent artists’ participation in these large-scale exhibitions. Worse yet, the rapid-fire pace required of the biennial connoisseur threatens to produce not the urban flâneur whose free meanderings lead to a greater interconnectedness with and knowledge of the modern city and its spectacles (as envisioned by Baudelaire), but rather an overwhelmed viewer whose fatigue and lack of access to thematic continuity preclude a clear understanding of artists’ messages and agendas, pointed and urgent as they may be.

Thus, Storr’s understanding of (in)visibility directly correlates with the viewer’s and the artist’s (in)ability to pay for or into it. In the case of the 2007 Venice Biennale, this stance left many potential contributing artists from Africa and the African diaspora wedged between two undesirable circumstances. On the one hand, they might face selection by a Western curator (Storr) whose exposure to African contemporary art largely started with his visit to DAK’ART in 2006, and who once mentioned to Chuka Nnabuife that he never knew that “there were so many high-ranking artists in Africa.”11 On the other, they could submit proposals to a committee chaired by Storr that would ultimately decide how contemporary African art would be showcased continentally—rather than locally or regionally—within the Venice Biennale.12

Art critic Chika Okeke-Agulu observed that the 2007 Venice Biennale’s call for proposals for this special African exhibition required a “budget of the proposed exhibition, and statement by the organizers regarding their plan for the total coverage of these costs including a list of the financing institutions and/or sponsors of the exhibition.”13 Rightly, Okeke-Agulu surmised that few African artists, collectives, or interested parties would be able to access the financing required by the Venice Biennale to participate, thus the conditions of its showcasing of African contemporaneity and speculating about the nature of contemporary Africanness ultimately undermined the initiative. What remains unresolved about the structure of biennials is the difficult relationship between transparency and equity. Can mega-exhibitions meaningfully generate dialogues about non-Western art that do not exoticize, dilute, or eclipse such art’s contribution to both global and local institutions and constituents?

Rem Koolhaas, European Flag Proposal, 2002. Image courtesy Rem Koolhaas and the Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

In support of Storr’s initiative, art critic Olu Oguibe wrote: “[I]f we are serious about building open societies on the continent, I suggest that it is time that we [as Africans] began to embrace transparent processes and open participation…”14 In response, Rasheed Araeen asks why “diasporic Africans [are] fighting for a Venice pie.” Araeen likens this process of inclusion to the commodification and fetishization of African contemporary practices—hurriedly “studied” by Western curators, then shoehorned into thematic frameworks largely created for the benefit of Western consumption, and finally anchored to the primacy of Western art historical discourses that African practitioners must subsequently revisit, challenge, adopt, transform, or appropriate.15 According to Araeen, Storr’s discomfort with African contemporary art in a biennial context points to the timely need for a biennial alternative—one that is quintessentially born of Africans, and potentially for Africans. In his view, responsibility for the dissemination of varying, potent narratives of Africanness in art rests with non-Western artists and curators who have yet to create a viable forum for an interrogation and integration of these marginalized interests. Storr has romantically suggested that the contemporary biennial is “a polycentric reality over which not even the consolidating tendencies of global markets and information technology can hold dominion.”16 However, his assessment neither addresses the biennial’s ongoing institutional relationships to these markets, nor explores how the biennial may serve as an impartial forum for art practices that openly criticize or resist such acts of consolidation and homogenization. The danger remains that cultural specificities, local tensions, unique colonialisms, and recoveries from or negotiations with looming power structures are lost in the mega-exhibition, because biennials render the art of the non-West as more accessible and “legible” by exhibiting and critiquing it in terms of the West’s more familiar histories, art movements, and aesthetic foundations.

For instance, an examination of Ghanaian artist El Anatsui’s Dzesi II (2006) in the 2007 Venice Biennale catalogue reveals African site-specificity in terms of its documented installation and a reconfiguration of aluminum packaging that loses its familiar branding in favor of a new, self-determined, localized, and material vernacular. Yet, Storr’s critique of the work aligns its form and technique with Sol LeWitt’s geometric patterning and Robert Rauschenberg’s Pop-ist recovery and use of quotidian materials. Storr’s approach positions Western contemporary practice as the mediating lens by which African contemporaneity must be read and understood. Moreover, when Storr reads El Anatsui’s practices as “deviat[ing] in important ways from LeWitt’s systems- based grid aesthetic even as they depart from anything that might pseudomorphically be misconstrued as traditional African craft,” he problematically reasserts the primacy of Western contemporary art movements with which subsequent practitioners must negotiate, while simultaneously creating awkward, neo-colonialist comparisons between the period specificities and successes of “Western minimalism” and gross generalities and understatements about “African craft.”17

Interestingly, in the section of the catalogue devoted to Sol LeWitt’s inclusion in the 2007 Venice Biennale, Storr draws no legitimizing parallels between LeWitt and non-Western practices and traditions with which his work might resonate. Storr’s “dialogue” thus appears to be a function of an unspoken cultural unilateralism that posits Western Modernism as a foregone conclusion requiring little socio-historical contextualization or non-Western mediation. Of greater concern are his surface readings of the appropriations, reclamations, and fluidities of postmodernity or antimodernity that he constructs as simple corollaries or derivatives of Western Modernism. In light of these observations (and many others), Storr’s insistence that the 2007 Venice Biennale did not appeal to a specific viewer is questionable. Given the tone of the catalogue, his appeal to a specific type of image reader—one well-versed in the canonical practices of Western art and largely ignorant of the African traditions and visual vernaculars that developed independently from, symbiotically with, or as counterpoints to Western models—is undeniable.

This persistent lens of Westernness also informs Storr’s readings of Odili Donald Odita’s works at the Venice Biennale. Storr brackets the artist’s own statement of purpose—deriving colors that are “the collection of visions from…travels locally and globally”—with his own claims about the works’ derivation from Western traditions of abstraction, such as Constructivism, Minimalism, Cubism, and Expressionism. Storr even has the Eurocentric temerity to characterize Odita’s purpose as “rejuvenating abstraction one hundred years after its invention.” By neglecting any inquiry into the specific characteristics of an abstract practice emerging from non-Western cultural milieus and by disregarding abstraction’s various appearances in cultures throughout human history, Storr ultimately fails to identify a discursive technique or approach—what Araeen might call the “mediative discourse”—that bridges Odita’s Nigerian sensibilities about color, culture, technology, and individual memory with the canonical traditions and Western movements that buttress Storr’s assessments of Odita’s work.18 In what ways do Western practitioners theorize, render, and employ color differently from their African, specifically Nigerian, peers? Storr asserts: “sub-Saharan African art…encodes nature or symbolizes relations between humans and natural or metaphysical forces” and Westerners “have historically, but often mistakenly, seen parallels to abstraction.” If so, why is Odita described as rejuvenating that model? If viewers examine Storr’s interpretation of the artist as one who “adumbrat[es] a set of coordinates that may be extended far beyond the confines of this exhibition, but will reliably gauge such qualities wherever they are found,”19 they might surmise that biennial artists and their works in general act as steady compasses that point back to the precedence of Western practice or to a “universal(izing)” aesthetic that is true for all peoples at all times. As opposed to Rem Koolhaas’s proposed overhaul of the European Union flag, in which the specifics of cultures and national identities give way to a more Modernist, generic, and reductive articulation of color bands loosely based on individual countries’ flags, any consideration of Odita’s work begs for a hasty return to those culturally specific contexts and influences that issue from the local and that ultimately complicate overly easy—and overly Westernize —explications of color, line, form, culture, and context.20

Odili Donald Odita, This And That, 2006. Acrylic on canvas, 81 3/4 X 109 In. Courtesy the artist And Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Indeed, the answer to meaningful engagement with African contemporary interests may not rest with permitted inclusion in the institutional grand narrative that is the Eurocentric biennial. For some curators, authentic cultural discourses arise when one jettisons reliance on the now-expected “shock-and-awe” components of glamorous exhibition parties, glossy exhibition catalogues, draw-card artists and curators, multi-million-dollar financial sponsorships, and the general gravitas of cities whose histories are familiar and well chronicled in the West. Johannesburg’s and Cape Town’s brief sojourns into the world of biennials may have been described by critics as ill-conceived or premature, but the failure of those mega-exhibitions also engendered a palpable desire to reconceptualize what a biennial event can be to local constituents and to those who view and contemplate the multiple interpretations of Africanness and identity as a globally interactive phenomenon.

Such failures of the biennial format have placed front and center the urgent need for a renegotiation of the terms of contemporary representation and equitable “visibility,” as seen in the growing numbers of alternatives to Venice’s century-old, mega-exhibition tradition. As curator Irit Rogoff notes:

The relationship between stability and circulation has grown strained. The stabilities of citizenship and emplacement and their related access to rights, protections, inclusions, situated knowledge, and legitimated cultural production are countered by an ever-increasing array of categories of those who cannot automatically assume such accesses: immigrants, migrant laborers, refugees, asylum seekers, diasporic communities…Such a level of bodily circulation has impacted on the very possibility of arguing “situated knowledge” simply as a series of direct relations between subjects, places, and epistemologies…21

Rogoff’s dichotomies of stability and circulation mirror the tensions of Modernism and Postmodernism that underpin the conventional biennial’s precarious situation as a Modernist form of exhibition and organization increasingly responsible for cataloguing an art world that openly disputes or disassembles these strategies of display and dissemination of knowledge. The consequence has been the consideration of the “post-biennial”—an event or “happening” that rejects the spatial conditioning, economic mobilizing, and thematic essentializing of the traditional biennial and relies on new strategies, technologies, and conceptual constructs to draw attention to emerging, often overlooked currents in the art world.

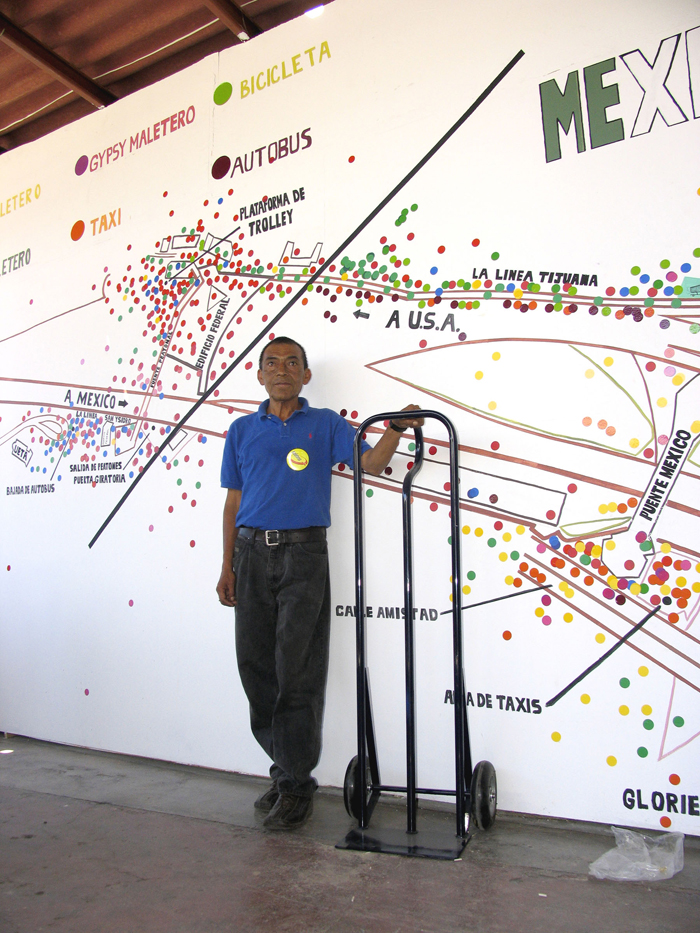

Mark Bradford, Maleteros, 2005. Installation project for inSITE05. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: Juan Carlos Avendaño. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Mark Bradford, Maleteros, 2005. Installation project for inSITE05. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: Juan Carlos Avendaño. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

For example, resistances to Western exhibition models can be seen in inSITE’s (quasi-)biannual performance- and arts-based programming on the border between Tijuana, Mexico, and San Diego Beach in the United States. Unlike traditional biennials that occur at predictable intervals, exhibit easily locatable works of art, and self-legitimize through the production of catalogues and promotional materials, inSITE focuses on the transient and tentative nature of border existence, as reflected in a changing body of works, performances, and activist interventions. This “anti-biennial,”22 as critic Jennie Klein calls it, explores the consequences of willingly unanchoring artistic expressions and making them more accountable to a vast range of viewing publics and mechanisms of sociocultural control and subversion than to the pomp and pedigree of established exhibitions. In the context of inSITE, invited artists explore the nature of transportation and migration through the U.S./Mexican border zone. For example, in the 2005 iteration of inSITE, Mark Bradford supplied existing maleteros (porters who help with the movement of goods along the San Ysidro border region) with brightly colored shopping carts, tethers, and other supplies needed for their work. Maps of the carts’ trajectories provided a new, recorded visibility of migrants, citizens, and the undocumented, and illustrate the porousness of the U.S./Mexico border. Bradford’s artwork both charted the frequent movements of people and goods in the region and celebrated the outing of a usually clandestine series of socioeconomic transactions.

Other works, such as SIMPARCH’s Dirty Water Initiative (2005), grappled with urgencies specific to the local environment. Dirty Water Initiative explored ways in which contaminated water might be purified through the creation of a solar-powered apparatus that could be both aesthetic (as a complex sculptural installation) and utilitarian (as a filtration device). Unlike artworks in traditional biennials, which usually maintain a temporary or socially disengaged footprint within their host cultures, SIMPARCH’s apparatus relied on the subversive nature of the “anti-biennial” as a means of rallying and sustaining social, economic, and urban rejuvenation, long after the official exhibition concluded.23

Ute Meta Bauer & Elke Zobl, Mobile_Transborder Archive, 2005. Trailer and mixed media, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artists.

SIMPARCH, Dirty Water Initiative, 2005. Installation project for inSITE05. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artists and inSITE05.

The collective’s process-based approach to art production mirrored other endeavors within the inSITE exhibition, including the Mobile_Transborder Archive (2005), a nomadic and extra-institutional repository that chronicled and distributed a changing body of border knowledge, including oral histories, films, personal photographs, and electronic resources. The relegation of materials usually confined to the gallery or museum to a small and mobile trailer acted as a powerful mechanism for linking grassroots community activisms,diverse constituents in the art community, and multidisciplinary modes of expression often incompatible with museological imperatives. Citing on its exterior panels Michel de Certeau’s suggestion that “the transformation of archive activity is the point of departure required for the narration of a new history,” the trailer refashioned the traditional interfaces of the biennial, allowing its “institutions” (given inSITE’s gestures of institutional destabilization) to better document the existences of those they seek to represent.

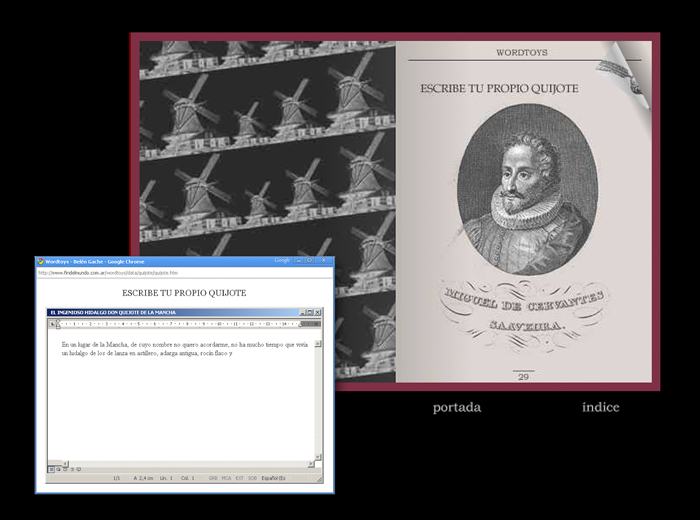

Such reconsiderations of the art world’s now-familiar rules of engagement have led to other speculations regarding the “post-biennial,” including Arte Nuevo InteractivA—a largely Internet-driven and DIY biennial project based in Merida, Mexico, that relies on virtual collaborations from participants around the world. The project’s coordinator and curator, Raúl Moarquech Ferrera-Balanquet, posits medium as one of the controlling elements of artistic expression that affects how, where, and by whom it may be seen. For Ferrera-Balanquet, the Internet functions as a potentially equalizing, relational presence—allowing some artists to focus more on the presentation and exchange of their ideas and permitting greater numbers of viewers to access those ideas regardless of their geographic location or socioeconomic status. Ferrera-Balanquet’s biennial links to Rogoff’s notion of the disintegration of stability and meaning, and further explores the representational consequences of circulation and flux-thinking of artistic expression as renegade, viral, and often uncontrollable. Similarly, Argentinean artist Belén Gache’s Wordtoys: Escribe tu Propio Quijote (2008) presents a Microsoft-like tabula rasa—a word-processing template that seemingly awaits the participant’s own creative input. However, try as one might as viewers attempt to write their own narratives on the screen, the grand narrative of Cervantes’s Don Quijote surfaces in Spanish with every keystroke—disallowing any visible deviation from an already-established text. The project recalls Jorge Luis Borges’s “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” in which Borges attempts to make an historical grand narrative accountable to the periods in which it is read, and Sherrie Levine’s appropriative “re-photography” of classic photographs by Walker Evans, Edward Weston, and others. Gache’s work cleverly mirrors the biennial’s ongoing and seemingly irreconcilable tensions between standard(izing) and resistant contemporaries, between the biennial’s historical embrace of certain modes of expression and the countless narratives that the mega-exhibition cannot accommodate.24 As much as Wordtoys might invite participation from diverse audiences, it also frustrates it—displaying instead a persistent reliance on a canonical Spanish text. As non-Spanish-speaking participants engage with the piece and observe its intractable insistence on a 17th-century Spanish vernacular, they also experience the same representational railroading that has transformed or altogether excluded artistic voices in more traditional, Western art biennials.

Belén Gache, Wordtoys, Escribe tu Propio Quijote (Write Your Own Quixote), 2008. Computer program with web-based interface.

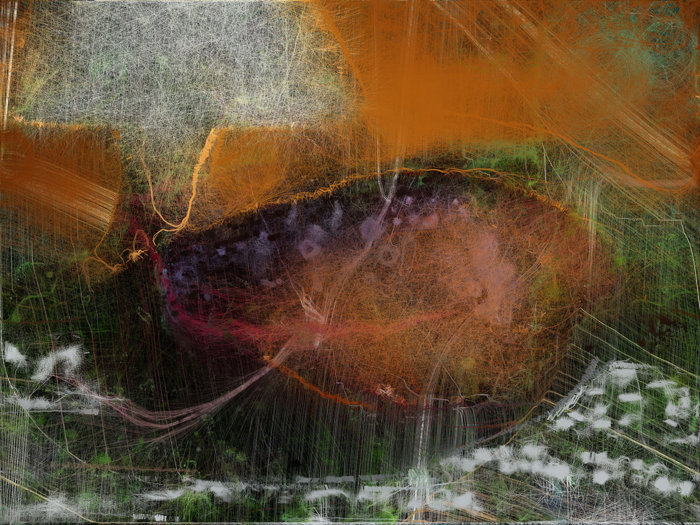

Other collaborations with viewers dictate the evolution of artists’ works, such as Leonardo Solaas’s Dreamlines (2006), in which viewers select keywords for the creation of a constantly changing dreamscape. For instance, typing in “art history” as the subject of one’s “dream” begins a pixilated and fractal-infused journey through cyberspace as Googled “hits” of the dream’s subject initially selected by the viewer morph in and out of relationship with one another. Through a reliance on digitally altered Google searches, the work confronts and camouflages the usual imperatives of value, chronology, aesthetic appeal, and order to create new figural and abstract forms and color fields. Here, collaboration results in an individually tailored experience, but also one outside the viewer’s (and even the artist’s) immediate control—what Ferrera-Balanquet describes as the necessary “laying claim to a new orientation and situation of contemporary art.”25 Solaas’s work readily illustrates the problems associated with both “glocality” and the consistency of meaning, as a constantly shifting body of Western-skewed search parameters ensures that the generated image will never be completely coherent, stable, predictable, or representative. As individuals collaborate with the artist, they also collaborate with a host of other parties connected to the Internet who, unbeknownst to them, alter the fixity of language and subject/object relationships.

In a manner similar to Arte Nuevo InteractivA, the Roaming Biennial of Tehran critiques the site-specific biennial as an outmoded, colonialist apparatus that is ill-equipped to offer a voice to artists practicing in locales that either inhibit forthright artistic expression or that remain largely inhospitable to the notion of cultural tourism. According to one of the Roaming Biennial’s founders, Serhat Köksal, globalization, and its insistence on a Kantian sensus communis, often conceals experiential disagreements and dissonances in favor of what Thierry de Duve calls “a definition of humankind as a community united by a universally shared ability for sharing feelings.”26 The Roaming Biennial of Tehran is described as “[a]n independent, low-budget, traveling exhibition which can be presented almost anywhere,” put together by curators who are more like “nomads, carrying artwork, objects, texts, and whatever, in a package no bigger than a medium-sized suitcase, preferably weighing less than twenty kilograms, so it can be carried on any cheap flight.”27 The Roaming Biennial of Tehran relies on Iranian and other non-Western diasporas as the foundations for contextualizing current events and other art practices in Western locales and has been staged so far in Istanbul and Berlin (both cities with identity crises rooted deeply in East vs. West, or European vs. Asian tensions). For example, Samin Tabatabaei’s Tower Jealousy (2008) subtly links architectural one-upmanship to the minaret, which is a ubiquitous spiritual structure in Iranian and Muslim culture. Another collective, Turkish graffiti artists FlyPropaganda, uses the minaret as a form of potent iconographic opposition to Western politics, power, and consumerism—by attaching two of the structures onto a picture-postcard of the White House. The simple, Photoshopped act conceptually destabilizes the familiarity and patriotism that have imbued this building for years, but also questions the structure’s representativeness and effectiveness as a symbol of contemporary “American” freedoms and liberties.

The success of the Roaming Biennial of Tehran relies heavily on artists’ willingness to forego stipends, as well as their usual concerns about framing, handling, and insurance, in exchange for participation in a range of mini-biennials that establish unique, ephemeral resonances with their various locales. Curatorial and artistic collaborations lead to makeshift, exhibition-style counterpoints to the explosion of mega-exhibitions—not only because of a marked reduction in bureaucracy, but also due to a commitment to new “biennial technologies” proving to be more effective at linking art-producing and art-consuming communities than site-specific exhibitions with limited durations. Facebook, Twitter, and Bebo are especially relevant in the context of the Roaming Biennial of Tehran because they have been at the forefront of younger generations’ communications about—and mobilizations against—the Iranian regime in recent years. They have sustained this biennial and rendered it less as an historical chronicle or catalogue and more as an agent of ongoing responsiveness and interactivity. Perhaps most importantly is this biennial’s awareness of its fringe status in relationship with larger and more established biennial traditions; its 2008 theme, “Urban Jealousy,” is based on the French term jalousie—a window through which one may observe, but never be observed.28 For the exhibition’s curators, visibility is a function of first exposing the commercial, geographic, cultural, and institutional obstacles to inclusion and then attempting to invent new image-driven insurgencies that can disrupt their primacy in the art world.

Already prompting a great deal of critical engagement, these new and emerging exhibition models for the viewing and contextualization of global art practices promise much for ensuring that underrepresented experiences and works continue to be seen—despite their potential incompatibility with the mammoth biennial traditions that often sideline, misrepresent, or altogether ignore them. Their strength is their unrepentant acknowledgement that Western biennials, such as the Venice Biennale, have perpetuated untenable tensions between the notoriety of works that are included there (as reinforced by Storr’s persistent understandings of “visibility” and representation as functions of Westernness) and the impossibility of seeing those that cannot be there due to the constraints of geography, financial resources, or curatorial ineptitude. The guiding ambition of the “post-biennial” or “anti-biennial” has been the formation of an ideological mission that transcends the limitations of the site-specific exhibition by drawing greater attention to artists, audiences, and changing ideas that don’t fit such rigid, site-specific, museological paradigms.

Leonardo Solaas, Dreamlines, 2006. Generative web-based application. http://solaas.com.ar/dreamlines/. Courtesy of the artist.

Leonardo Solaas, Dreamlines, 2006. Generative web-based application. http://solaas.com.ar/dreamlines/. Courtesy of the artist.

Leonardo Solaas, Dreamlines, 2006. Generative web-based application. http://solaas.com.ar/dreamlines/. Courtesy of the artist.

Leonardo Solaas, Dreamlines, 2006. Generative web-based application. http://solaas.com.ar/dreamlines/. Courtesy of the artist.

The economic imperatives of contemporary biennial programming that have often prevented truly global participation have also begun to impact more traditional mega-exhibitions’ repertoires of artists, many of whom have become openly critical of the biennial’s window-dressing of strained relationships between artists, institutions, and viewers. In the 16th Biennale of Sydney, disgruntled Australian artist Tony Schwensen hastily hosted a sausage sizzle in front of the Museum of Contemporary Art, one of the Biennale’s main venues, to raise funds for the adequate payment of future participants in the 2010 Biennale in a work entitled Fundrazor (Fuck you pay me) or Who gets to sit at the pointy end of the plane? (2008). Along with the Rotary Club-like fundraiser, Schwensen proposed the framing of a check for $703.12 in proceeds and its placement in the Museum of Contemporary Art as subtle and understated reminders of the disparity between bloated biennial budgets and artists’ often-meager livelihoods.

In a much more dramatic fashion, Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla unsuccessfully attempted to auction off the Sydney Biennale entirely to Sotheby’s at a reserve price of $2 million, after the Biennale’s creative director, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, asked the artistic duo to make a work for the exhibition with no financial compensation. Allora and Calzadilla’s collaborative work, reduced to a fake, voided, inkjet-printed check, represents the crisis of contemporary art in a fiscal sense. Their gesture questions the value, scope, intent, and influence of the contemporary biennial, and begs for lasting exhibition counter-models and strategies that interconnect more readily with artists’ practices. Their work also reminds viewers that the spatial and object-focused dynamics of the biennial often eclipse those artists’ practices that dwell in the realm of idea and immateriality.

Ultimately, Philippe Vergne suggests: “The question of globalization and art is about transforming the structure of Western modernity so that one is able to write other histories of forms…practices, [and] other art histories.”29 Several crucial tensions surface in his assessment, including: (1) the assumption that Western modernity, in terms of artistic expression, still subscribes to or exists within a structure that may be transformed; (2) the presumption that questions of globalization are initiated, facilitated, or accommodated solely by Western interests; (3) the suggestion that the writing of history can be accomplished unilaterally by speaking for, rather than about, the non-Western subject; and (4) the implication that non-Western histories and experiences, as reflected in art, require the legitimizing intervention of Western critical, archival, and expository strategies. The contemporary biennial can no longer fashion as its goal the production, articulation, or perpetuation of universal tastes—what Carlos Basualdo describes as the conventional biennial’s “encyclopedic ambition.”30 Moreover, truly inclusive biennials may no longer render the “global” solely as a function of the number of represented artists in any one exhibition, but rather in terms of how successfully artists, artworks, and audiences interact with one another—despite the social, political, economic, and cultural circumstances that may complicate or thwart such relationships. If globalization produces one consistent and problematic effect in the context of the contemporary biennial, it would be that it proffers a spatial, image-driven fantasy of an experiential interconnectedness and public camaraderie that cannot or does not yet exist.

The future of the contemporary biennial rests with its ability to navigate the politically charged nuances between inclusion and engagement, between cultural visibility and the reification of difference, between unmediated display and truly open dialogue. Only then will visitors—in whatever form visitation of or interaction with the future biennial may take – unearth the connective tissue between self-awareness and unnoticed histories: a “private discovery” irrefutably couched in social responsibility and cultural accountability.

Royce W. Smith is assistant professor of modern and contemporary art history in the College of Fine Arts at Wichita State University. He will be the chief editor of The Journal of Contemporary Festivals and Biennials, to be published for the first time by Intellect Press in 2012. He is also author of Biennale!: Representation, Crisis, and the Contemporary Mega-Exhibition, due to be published by I. B. Tauris in early 2012.